The little-known legislative rules that govern the legislative process in the Illinois House of Representatives give the House speaker extraordinary power to orchestrate the legislative or political outcomes he or she wants.

Those rules allow the speaker to influence the makeup of legislative committees; how lawmakers vote; and when, if ever, the bills get voted on. But the most obstructive rule of all keeps bills – even those with popular support, such as term limits – from ever seeing the light of day. The speaker, and not the General Assembly, has the power to decide what has the chance to become law.

Virtually no state grants the types of powers to its legislative heads that Illinois grants to its speaker.

Those rules have contributed to the failed policies that exist in Illinois today and to the fiscal debacle Illinoisans must contend with as they try to make ends meet.

Not surprisingly, the public knows little to nothing about these stealth rules, how they operate and how they ultimately hurt the very public the General Assembly is meant to serve. It’s just another form of the corruption – the games politicians play – for which Illinois is famous.

If Illinois is ever going to see the economic and spending reforms it needs to bring back growth, jobs and fiscal sanity, lawmakers need to take the power back from the speaker. In particular, they need to rescind the speaker’s power to:

- dole out committee chair positions and the stipends that come with them,

- control who votes in committees,

- dictate when a bill will be called for a vote, and

- control what bills make it to a vote.

When it comes to checking the speaker’s power and returning democracy back to the state legislative process, Illinois can follow the example of any of a number of other states.

Methodology

The basis for the majority of figures in this paper is a search of the rules of each legislative chamber in the 50 states. Illinois Policy Institute emailed or called the chief clerks of the houses of representatives, secretaries of the senates, or legislative research organizations of the state legislatures for confirmation of the findings and inquired about each chamber’s customs and practices regarding committee substitutions, calendaring of bills, and removing bills from committee. Seventy-four of the 97 chambers contacted responded to the Institute’s inquiries.

The speaker doles out committee chair positions and the stipends that come with them

The problem: Illinois’ House leadership wields unchecked power over the 49 legislative committees that preside over issues ranging from agriculture to veterans affairs. Current legislative rules give the speaker sole discretion to give and take away committee chair positions – and the generous stipends that accompany them – as he pleases. This type of power is uncommon in other legislative chambers throughout the country.

How it plays out: Legislative rules create legislative committees as a way to vet bills in smaller groups before the entire House or Senate debates or votes on them. Each of the House’s nearly 50 committees has a dedicated chair that runs its committee meetings and otherwise acts as the head of that committee.

Under House rules in Illinois, these committee chairs are appointed by and serve at the pleasure of the speaker. This means the speaker may remove and replace committee chairs for any reason at any time. Additionally, the speaker can create new special committees, and thus dole out even more chair positions.

The speaker’s influence doesn’t end there. Each of these committee leadership positions comes with a generous $10,000 yearly stipend. Those stipends help boost the pensionable salaries of lawmakers who participate in the state pension plan, making the positions much more attractive than one might guess at first glance.

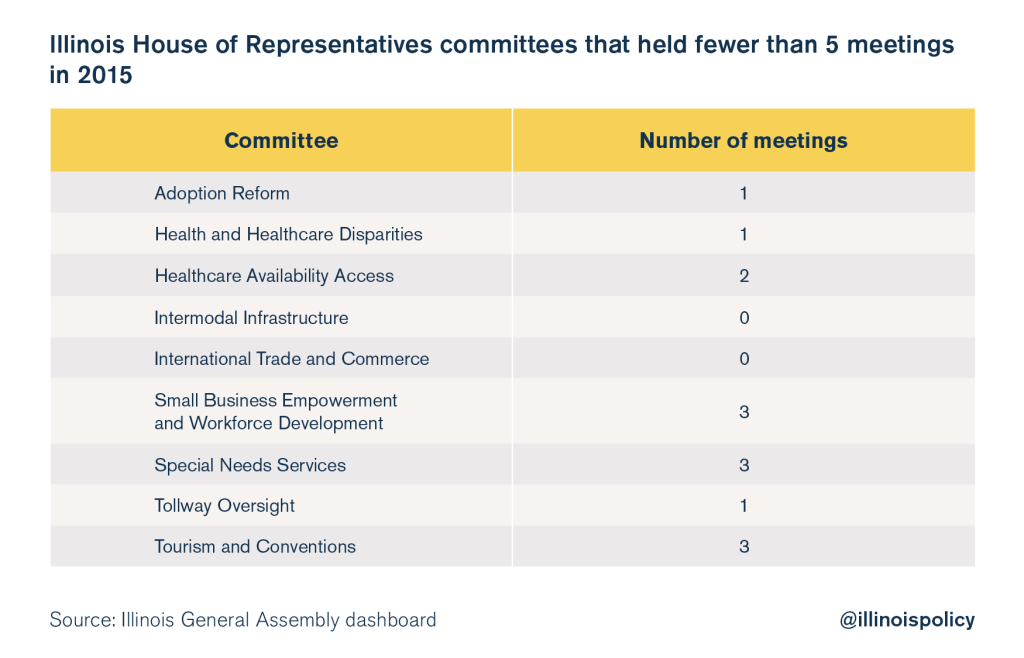

Oftentimes, these committee positions do not even require much work to justify the extra pay. In 2015, nine committees had fewer than five meetings, and two committees did not meet at all.[1]

The power to hand out committee appointments and stipends is not limited to the House, nor is it a partisan issue: All four chamber leaders have the same power to hand out stipends to the members of their parties, using appointments as a reward for loyalty or withholding them as a punishment for disloyalty.

But that power means much more in the hands of the majority party.

The possibility of losing a leadership appointment and stipend creates the temptation for lawmakers to side with their leadership rather than the constituents they’re meant to represent. Party discipline rarely wavers.

When it does, there are consequences. This was in full view in January 2009, when state Rep. Ken Dunkin, D-Chicago, missed a vote to impeach then-Gov. Rod Blagojevich.[2] House Speaker Michael J. Madigan in turn refused to reappoint Dunkin as chairman of the Tourism and Convention Committee until June 8,[3] leaving the committee unable to hold meetings for the span of that time.

The solution: When it comes to checking the speaker’s power to appoint committee leaders, Illinois has plenty of examples to follow.

In 13 state legislative chambers, committee chairs are appointed by a designated committee, often known as a “committee on committees.”[4] The speaker may appoint the members of a “committee on committees,” but that committee votes to appoint the leadership of all the other committees in the chamber, providing a check on the speaker’s power.

In the Arkansas,[5] South Carolina,[6] and Virginia[7] senates, committee chair positions are based on seniority: The committee members who have served the longest become the leaders of the committees.

In other states, the process varies. For example, in the South Carolina House, although committee members are appointed by the speaker, committee chairs are elected by the members of the committees themselves.[8] And while Alaska[9] and Hawaii[10] allow the leadership to appoint the chairs, the appointments must be approved by a majority vote of the chamber. In Nebraska, chairs are elected by secret ballot on the floor of the legislature.[11]

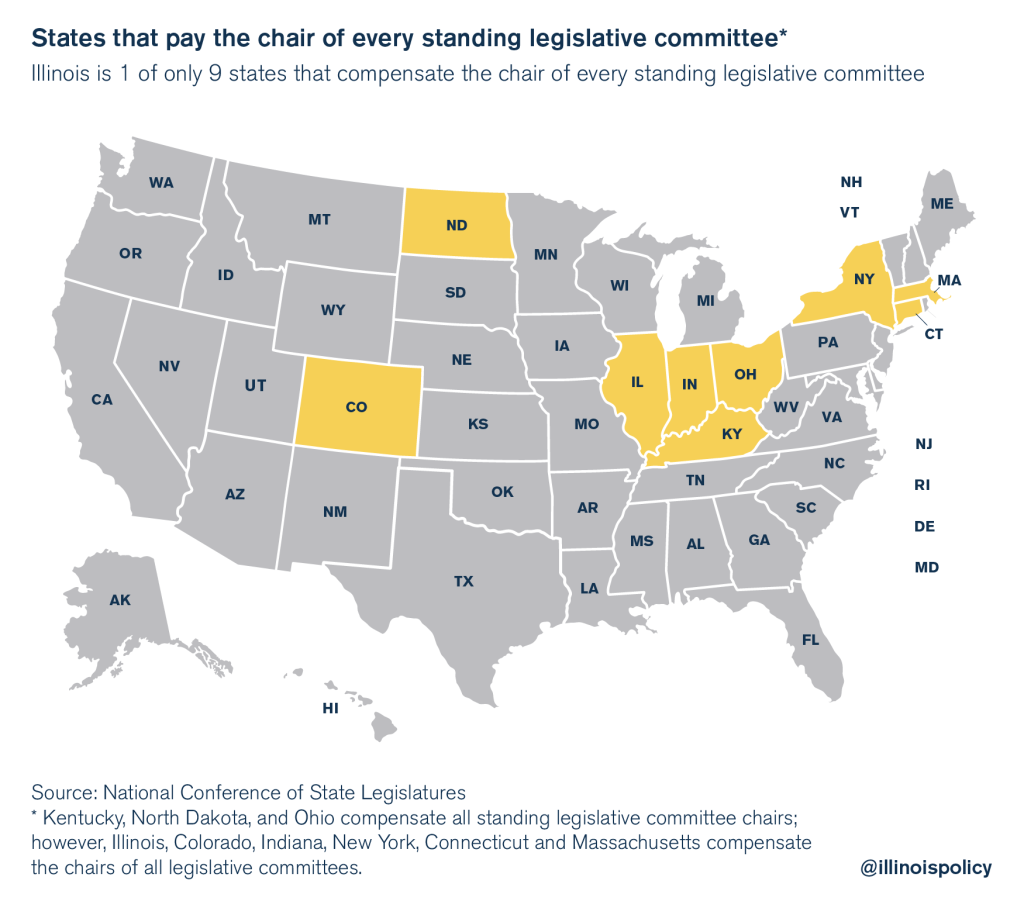

And while most states do allow the speaker to appoint committee chairs, most of them do not come with the same generous stipends. In fact, more than two-thirds of the committee chairs in the nation’s 99 state legislative chambers receive no compensation for their committee leadership positions.[12]

Illinois is 1 of only 9 states that provide stipends to all standing committee chairs: The rest of the states that compensate committee chairs reserve stipends for leaders of select committees, such as appropriations committees. [13]

Most states realize that leadership appointments are attractive without any accompanying pay increase. The added perk of stipends only gives lawmakers that much less incentive to cross their leadership. Given this reality, Illinois should at least require the majority to approve committee chair appointments, as is done in Alaska and Hawaii.

Better yet, Illinois should eliminate committee leadership stipends entirely.

- The Illinois House is 1 of only 18 legislative chambers to compensate every standing committee chair.

- More than two-thirds of state legislative chambers give no additional compensation to committee chairs whatsoever.

- Eight of Illinois’ legislative committees have not even held a meeting in 2016, as of Nov. 10, 2016.[14]

The speaker controls who votes in committee

The problem: The House speaker has the power to substitute committee members at will to ensure he or she gets gets the desired votes and to protect committee members from taking votes that are unpopular in their districts.

How it plays out: The role of each legislative committee is to debate committee-specific bills and to vote on whether to send those bills to the respective chamber for consideration. In most states, committee members are on record – for or against a bill – each time they take a committee vote.

In Illinois, however, the speaker can appoint temporary replacements for any committee member who is ill or “otherwise unavailable.” This means that if a lawmaker does not want to be on the record for taking an unpopular vote, the speaker can swap out that member for one in a safe seat who will not face competition.

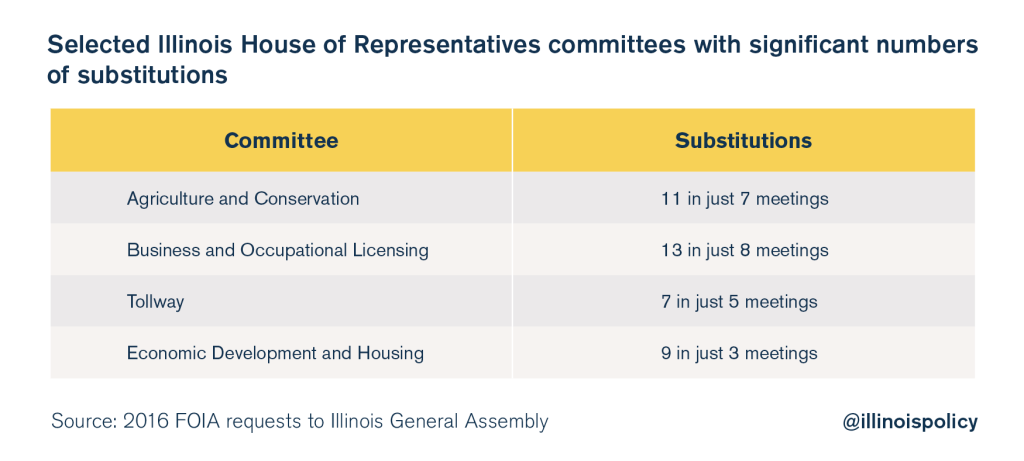

This is not an uncommon occurrence in some committees. For example, the Committee on Personnel substituted members in every one of its 16 meetings from January to June 2016.

That is not the only committee rotating members as necessary. As examples, the following committees had a significant proportion of substitutions:

Using this power of substitution, the speaker can swap out members to protect them from accountability for their votes.

Members of the minority party can make committee swaps as well, but with the speaker appointing the chairs and the majority of each committee, the majority party has more room to take advantage of them. Committee votes may even be held up until substitutions can be made. With these substitutions, the speaker can tailor the committees for each vote to maximize political benefit.

This means no one but the speaker can be sure who will vote in committee or how they will vote.

The solution: Illinois is 1 of 29 legislative chambers found to have legislative rules explicitly authorizing temporary replacement of committee members.[15] Seventy legislative chambers were found to have no rule specifically authorizing temporary replacements.[16] In response to Illinois Policy Institute’s inquiry of those states, at least 33 of those chambers have confirmed either that temporary replacements cannot be made or else are not made in practice, in stark contrast to Illinois’ extensive use of temporary replacements. Just seven of the chambers responded that they allow temporary replacements of committee members, and 25 did not respond.

Illinois should explicitly prohibit such temporary replacements. Committee members should be held accountable for their attendance and for their votes. When lawmakers are absent from a vote on the floor, they should simply lose their vote.

- The Illinois House is 1 of 29 legislative chambers to explicitly authorize the substitution of committee members in their legislative rules.

- Seventy legislative chambers were found to have no rule explicitly authorizing temporary replacements.

- In an inquiry of the chambers with no rule found on temporary replacements, 33 reported that they do not make use of substitutions in practice, or else prohibit them entirely. Only 12 reported that they do make use of substitutions. Twenty-five did not respond.

- In 2016, Illinois legislative committees have already made over 600 substitutions.[17]

Only the speaker knows when a bill will be called for a vote

The problem: In Illinois, there is no strict schedule for when bills will be called for a vote on a given day, and lawmakers are often caught scrambling. The speaker can call bills at the time of his or her choosing, leaving lawmakers flat-footed.

The lack of a proper bill calendar makes a mockery of the legislative process and ensures that lawmakers are unprepared, stifling real debate.

How it plays out: State legislatures across the country establish calendars to let lawmakers know what bills will be called for a vote and when. Lawmakers in those states can come prepared for discussion and debate on the bills to be voted on that day.

In Illinois, the speaker sets the schedule of the bills to be heard, and a daily calendar is set. But that’s where the similarities to other states end.

At the height of the legislative session, there are typically 100 bills and resolutions on the speaker’s list – already many more than can be voted on in one day. For example, on May 12, 2015, there were 137 bills or resolutions on the calendar. The next day, there were 147.

But there can be many more. Just two days later – May 15, 2015 – there were 244 bills scheduled on the calendar.[18] Yet only 16 bills were acted on that day.[19]

The calendar process is dysfunctional.

Even more, the rules allow the speaker to change “any order of business at any time.”[20] This means that not only are there more bills than the House can vote on but that the speaker can call those bills in any order he wants, regardless of the calendar.

This allows him to make sure his supporters are in the chamber before calling a bill, or to call a vote after opponent lawmakers have left the chamber. Rank-and-file lawmakers are left with no idea when any particular bill will be heard, if at all. That limits their ability to prepare for and research that bill, and in turn, their ability to represent their constituents.

The solution: Lawmakers in most other states don’t have to guess when their bills will be voted on.

Many states require the legislature to vote on bills by number, in the order the bills leave a committee or as set by a specific committee. Changing the order of business often requires approval by at least a majority of the chamber.

Diverging from the set calendar often requires a special order or a special order calendar setting a specific future time to consider a bill. Illinois is 1 of only 7 other states found that give one member the ability to set special orders, and it is 1 of only 3 states to do so without notice or regardless of objection by a majority of the chamber.[21]

More than one-third of states do not even have rules providing for special orders or special order calendars, and almost two-thirds of the states that have a rule providing for a special order require either majority or supermajority support to place a bill on a special order of business.[22]

Remarkably, Illinois is 1 of only 3 states found to have an explicit rule authorizing the presiding officer to skip from bill to bill with no advance notice. Only the Georgia House[23] and the Oklahoma Senate[24] were found to give their presiding officers similar power through their rules.[25] Maryland allows the presiding officer to determine the order only if a majority of the chamber does not object.[26] At least 55 chambers have confirmed that the order in which bills are called is set beforehand. Twenty-two chambers have not yet responded as to whether the presiding officer can call bills in any order.

Some states make up for this by not setting as many bills on the calendar. For example, in Idaho, at the end of session the calendar could have as many as 40 bills, and in Colorado it can range anywhere from two to 40 bills depending on the time of year – nowhere near the number of bills that can be on the calendar in Illinois. Ohio[27] and Virginia[28] provide a better example, however. In these states the order of bills to be called is set beforehand, subject to a motion to call them out of order or with approval from the other party.

This is the example Illinois should follow. Illinois should require bills to be read in a set and predictable order and ensure lawmakers know exactly when any given bill will have a vote.

- Illinois is 1 of only 3 states found to have an explicit rule authorizing the House speaker to skip from bill to bill with no advance notice. Only the Georgia House and the Oklahoma Senate were found to give their presiding officers similar power through their rules.

- In an inquiry of other state legislative chambers, at least 55 have confirmed that bills are called in a predetermined order.

- While 22 state chambers confirmed that they allow the presiding officer to call bills out of order, Illinois, Georgia and Oklahoma are the only states found to explicitly authorize the speaker to change the order in their legislative rules without any check by the rest of the body. Twenty-two states did not respond.

The speaker controls what bills make it to a vote

The problem: The speaker, unlike his or her counterparts in most other states, has the power to kill bills, even those that have popular support and deserve true floor debate, by virtue of the power to handpick the majority of the Rules Committee members. That committee determines whether a bill will be sent to a substantive committee for deliberation or simply sit in the Rules Committee until it dies.

How it plays out: Many state legislative chambers have established rules committees that retain various responsibilities such as writing the chamber rules and hearing or reporting on proposed amendments to the rules.

In Illinois, however, the Rules Committee does more.

When a lawmaker introduces a bill in the House, it automatically goes to the House Rules Committee. The Rules Committee is meant to sort bills and send them to the appropriate committees. But, in reality, the committee can sit on bills that the speaker opposes by never acting on them. The bills effectively die through inaction.

It is not easy to get a stuck bill out of the Rules Committee without approval. In order to do so, three-fifths of both the minority and majority caucuses must sign a petition – and each member of those three-fifths must also become a sponsor of the bill. The other way to get a bill out of the Rules Committee – a “motion to discharge” – requires unanimous consent of the House, a punishingly high hurdle. In contrast, it simply takes approval of the majority of members to get a bill out of a substantive committee.

Efforts to get a bill out of the Rules Committee by unanimous consent – to effectively bypass the committee – have been largely a symbolic gesture in Illinois. In a search of the legislative journals and transcripts, such a motion has only been found six times in the current General Assembly, and each time the motion has failed.[29]

A search of the previous General Assembly revealed that such a motion was attempted 14 times and failed 14 times.[30] In fact, there was no record of a successful attempt to discharge a bill from the Rules Committee since the House rules were changed in 2013 to require approval from the Rules Committee for a bill to be sent to substantive committees. Before 2013, the rules guaranteed that every bill would be sent to a substantive committee in the first year of the two-year session.

As it stands under current rules, however, no bill has a realistic chance of bypassing the Rules Committee if a majority of the committee members oppose it.

For example, in May 2015, state Rep. Jim Durkin, R-Western Springs, filed a bill to limit the term of members of the General Assembly. But Madigan opposed this bill, which had the potential to end the speaker’s career prematurely. So, instead of assigning the bill to committee, the Rules Committee held it so the bill would never be heard. Even though 4 of 5 Illinoisans support term limits,[31] the bill died in Rules Committee.

And while the rest of the chamber has to go through the entire committee process to move a bill, the speaker and the Rules Committee can avoid the process of committee vetting altogether by setting bills on the special order of business.

Whether a bill makes it to a vote is almost entirely in the speaker’s hands.

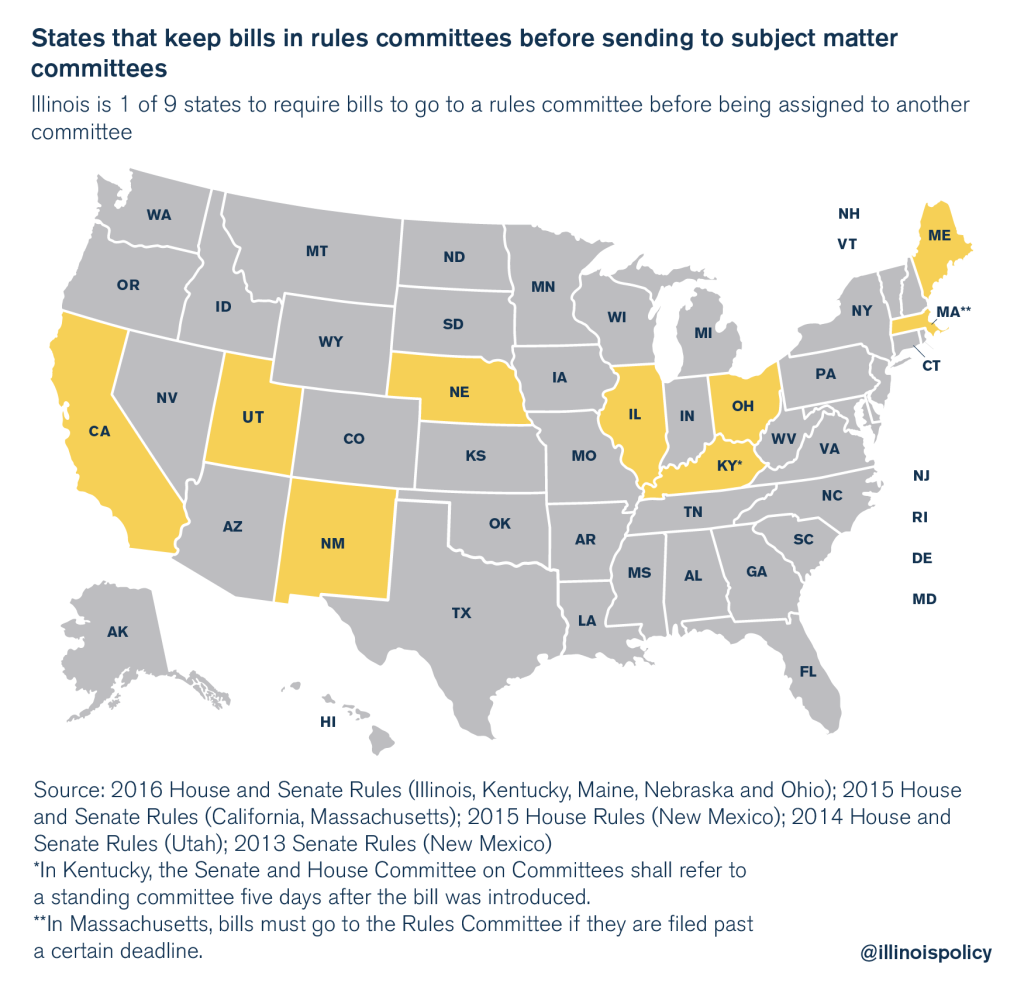

The solution: Forty-one states do not require bills to go through a rules or similar committee before being sent to a substantive committee, while in Illinois, every bill must go through the Rules Committee.[32]

Of the states that do not even require bills to go to a rules committee first, more than 55 percent require a simple majority to either sign a petition or support a motion to discharge from a committee.[33]

In fact, the Hawaii[34] and Missouri[35] houses only require support from a third of chamber members.

In the Minnesota House,[36] a chief author can eventually demand a bill be returned to the House if it is not voted on in committee.

In the Rhode Island House, the sponsor of a bill can request that a committee consider the bill. If the bill is not considered after a set period of time, the sponsor may ask that the speaker order the discharge of the bill.[37] In the Rhode Island Senate, a sponsor can compel a committee to consider a bill after a certain period of time.[38]

In Idaho, any member can get a bill out of a committee unless opposed by a majority of the members of the chamber.[39]

Even states that do not provide procedures on getting a bill out of committee sometimes provide for rules that would force committee action on those bills.

For example, while forcing a bill out of committee in the North Dakota House[40] requires unanimous consent (except for certain categories of bills), no bill or resolution may be held in a committee for more than 30 legislative days, unless granted an extension by the House. A bill introduced after a deadline must be reported back to the House within five legislative days. Any bill not reported back in time will automatically be placed on the calendar.

Illinois should not let good bills die in the Rules Committee just because the speaker opposes them and the Rules Committee won’t act on them. At the very least, majority support should be sufficient to send a bill to another committee from the Rules Committee.

Better yet, Illinois should require the Rules Committee to refer the bill to a substantive committee based on subject matter after a short period of time, such as five days after introduction, as is the case in Kentucky. If a bill has enough support, let lawmakers vote yes or no. That’s their job.

- Illinois is 1 of 9 states to require bills to go to Rules Committee before being assigned to another committee.

- Of the nine states that require bills to go to a rules committee first, only Maine, with no discharge procedure whatsoever, makes it more difficult to get a bill out of the committee.

- Forty-one states do not require bills to go to a rules committee before being sent to substantive committees. No state other than Illinois requires a supermajority to sponsor a bill in order to force it out of a rules committee.

Conclusion

Taken separately, Illinois’ legislative rules add to the speaker’s power in the House. Taken together, they give the speaker power over it. Compared with legislative leaders in other states, Illinois’ speaker has unprecedented power to control the legislative and political agenda. This power overshadows the will of the people and effectively silences their voice if it happens to disagree with the speaker. Changes in these legislative rules are a step toward restoring the balance of power in favor of the people of Illinois.

Endnotes

[1] The Business Growth & Incentives Committee, which also did not meet in that time, did not have a committee chair assigned. Illinois General Assembly Dashboard.

[2] House Journal, 95th Gen. Assembly, 299th Legis. Day 56 (January 8, 2009).

[3] Eric Naing, “Politics Blamed for House’s Two Idle Committees,” Springfield State Journal-Register, April 3, 2009; House Journal, 96th Gen. Assembly, 67th Legis. Day 5 (June 22, 2009).

[4] The Selection of Committee Chairs, National Conference of State Legislatures (last visited September 25, 2016).

[5] Parliamentary Manual of the Senate, 90th Gen. Assembly (Arkansas, 2016), 7.02; 2013 version.

[6] Rules of the Senate, 121st Gen. Assembly (South Carolina, 2016), Rule 19(E).

[7] Rules of the Senate (Virginia, January 13, 2016), Rule VIII(20)(a).

[8] A House Resolution to Adopt the Rules of the House of Representatives for the 2015 and 2016 Sessions of the General Assembly (South Carolina, 2015-2016), Rule 1.9.

[9] Alaska State Legislature Uniform Rules (1981), 12th Legis., Rule 21(a) (amended 2012).

[10] Rules of the House of Representatives (Hawaii, 2015-2016), Rule 11.2; Rules of the Senate (Hawaii, 2015-2016), Rule 13.1.

[11] Rules of the Nebraska Unicameral Legislature, 104 th Leg., 2d Sess. (2016), Rules 1, § 1, 3, § 8.

[12] See 2016 Survey: Additional Compensation: State Senate Leaders, National Conference of State Legislatures; 2016 Survey: Additional Compensation: State House/Assembly Leaders, National Conference of State Legislatures.

[13] See 2016 Survey: Additional Compensation: State Senate Leaders, National Conference of State Legislatures; 2016 Survey: Additional Compensation: State House/Assembly Leaders, National Conference of State Legislatures.

[14] Click on the “view committee hearings” and click the “previous hearings” tab.

[15] See Appendix B.

[16] See ibid.

[17] Data gathered from 2016 legislative committee FOIA requests.

[18] Illinois General Assembly, Regular Session House Calendar, May 15, 2015.

[19] House Journal, 99th Gen. Assembly, 48th Legis. Day 2 (May 15, 2015).

[20] Rules of the House of Representatives, 99th Gen. Assembly (Illinois, 2016), Rule 43(a).

[21] See Appendix D.

[22] See ibid.

[23] Order is determined by the Rules Committee or “as otherwise directed by the Speaker.” Rules, Ethics, and Decorum of the House of Representatives, Rule 52 (Georgia, 2015).

[24] The Oklahoma Senate allows the president to determine the order that legislation will be considered, and does not guarantee a right to a hearing on any legislation. See Senate Rules for the Fifty-fifth Oklahoma Legislature, Rule 8-22(B.) (2015-2016).

[25] See Appendix C.

[26] Maryland House Rules, Reg. Sess., Rule 7(b) (2016); The Senate of Maryland Rules, Reg. Sess., Rule 7(b) (2014).

[27] Rule 75, Rules of the Ohio House of Representatives, The Ohio Legislature 131st General Assembly, (last visited Sept. 25, 2016); Rule 8, Rules of the Ohio Senate, The Ohio Legislature 131st General Assembly, (last visited Sept. 25, 2016).

[28] Rules of the House of Delegates, Rule 52 (Virginia, 2016); Rules of the Senate, Rule IX(25)(a) (Virginia, 2016).

[29] House Journal, 99th Gen. Assembly, 48th Legis. Day 2 (May 15, 2015); 99th Gen. Assembly, 68th Legis. Day (June 30, 2015); 99th Gen. Assembly, 69th Legis. Day (July 1, 2015); 99th Gen. Assembly, 71st Legis. Day (July 9, 2015); 99th Gen. Assembly, 73rd Legis. Day (July 21, 2015); 99th Gen. Assembly, 77th Legis. Day (August 12, 2015).

[30] House Journal, 98th Gen. Assembly, 8th Legis. Day (January 29, 2013); 98th Gen. Assembly, 9th Legis. Day (January 30, 2013); 98th Gen. Assembly, 21st Legis. Day (February 28, 2013); 98th Gen. Assembly, 28th Legis. Day (March 13, 2013); 98th Gen. Assembly, 47th Legis. Day (May 1, 2013); 98th Gen. Assembly, 56th Legis. Day (May 16, 2013); 98th Gen. Assembly, 113th Legis. Day (April 2, 2014); 98th Gen. Assembly, 137th Legis. Day (May 23, 2014); 98th Gen. Assembly, 139th Legis. Day (May 27, 2014); 98th Gen. Assembly, 140th Legis. Day (May 28, 2014); 98th Gen. Assembly, 151st Legis. Day (December 3, 2014).

[31] “Gas Tax ‘Lockbox,’ Term Limits and Independent Redistricting Draw Big Support,” Paul Simon Public Policy Institute, press release, October 5, 2016.

[32] See Appendix F.

[33] See Appendices E and F.

[34] Rules of the House of Representatives, 28th Legis. (Hawaii, 2015-2016), Rule 37.

[35] Rules of the House of Representatives, 98th Gen. Assembly (Missouri, 2015), Rule 36.

[36] Permanent Rules of the House of Representatives 2015-2016 (Minnesota, 2016), Rule 4.31. (Rule 4.30 requires a majority vote to recall a bill from committee.)

[37] H.R. Res. 2015-H5258, Rule 12(g) (Rhode Island, 2015).

[38] Rules of the Senate (Rhode Island, 2015), Rule 6.11.

[39] House Rules (Idaho, last visited September 25, 2015), Rules 34 and45.

[40] House Rules, Senate and House Legislative Manual, 64th Legis. Assemb., Rules 331, 509 (North Dakota 2015-2016).