Pensions 101: Understanding Illinois’ massive, government-worker pension crisis

By Ted Dabrowski, John Klingner

Pensions 101: Understanding Illinois’ massive, government-worker pension crisis

By Ted Dabrowski, John Klingner

The state’s pension crisis – the worst in the nation – hurts everyone in Illinois, from state workers and lower-income residents to retirees and taxpayers.

The growing cost of pensions has trapped the state, the city of Chicago, and hundreds of municipalities in financial crises, forcing many governments to raise taxes and shortchange programs on which lower-income Illinoisans rely.

Younger government workers are also trapped in state and city pension systems, forced to pay into broken pension funds from which they may never see benefits.

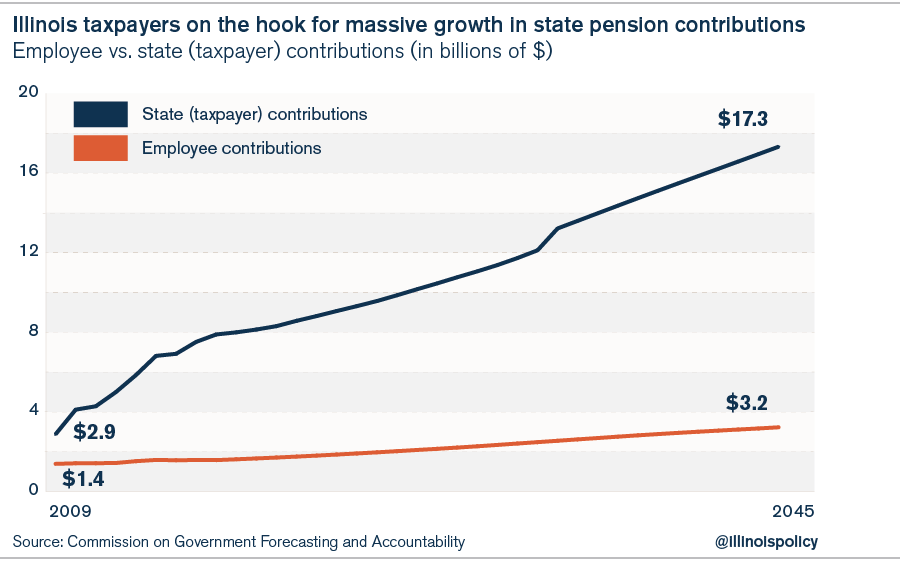

The crisis threatens to burden taxpayers with massive, ever-escalating taxes to bail out a system that is not sustainable – government-worker pensions consume a fourth of the state’s budget.

Major credit agencies, such as Moody’s Investors Service and Fitch Ratings, have taken note and have given Illinois the lowest credit rating in the nation – just three notches above junk status.

This report explains what government-worker pensions are, how Illinois’ pension crisis was created, and the potential solutions to the crisis.

What are pensions?

A government-worker pension in Illinois is a defined-benefit, or DB, retirement plan under which employees are supposed to receive annual benefits during retirement. In general, a DB plan works by having an employee and employer contribute a set percentage of the employee’s annual salary to a pension fund over the course of the employee’s career. The pension fund invests this money in the stock market – the same markets in which 401(k)s invest. These investments are expected to grow enough to meet the fund’s future pension obligations.

In exchange for these contributions, the pension fund promises a guaranteed amount of money every year to the employee for life once he or she retires. In addition, the amount a retiree receives increases each year through an annual cost-of-living adjustment, or COLA. In Illinois, COLAs automatically increase a retiree’s yearly benefit, typically by 3 percent each year.

Employees do not own or control their own retirement funds under a pension system, nor do they have their own accounts. Instead, state officials and politicians control the pool of funds, allowing them to use workers’ retirement dollars as a political slush fund.

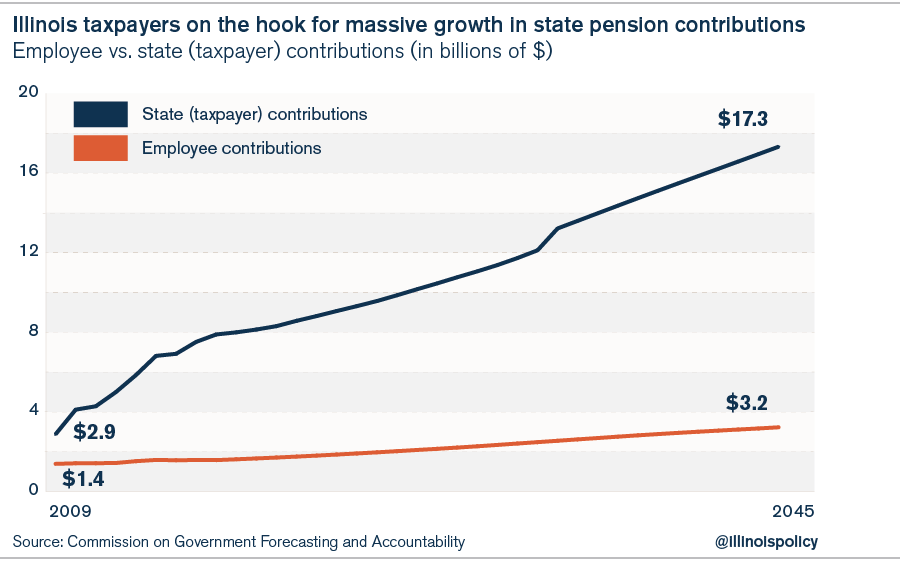

Another major weakness of DB plans is that if funds don’t have enough money to pay out future benefits, it’s taxpayers who must bail them out. That’s precisely what’s happening in Illinois today. Taxpayers now contribute more than three times what state workers contribute to their own retirements.

Illinois is home to 667 government pension funds

Illinois has 667 government-worker pension funds that are supposed to provide retirement security for more than 1 million government workers and retirees. Pension funds in each of these groups – the state, Chicago and other municipalities – are in crisis. Those funds include:

- Five state-run funds that cover downstate and suburban teachers, state employees, state-university employees, judges, and Illinois lawmakers

- 355 suburban and downstate police pension funds, 296 suburban and downstate firefighter pension funds, and a pension fund for suburban and downstate municipal workers

- Seven pension funds in Chicago and three pension funds in Cook County

A better alternative: 401(k)s

In contrast to DB plans, in a defined-contribution, or DC, plan such as a 401(k), both the employer and the employee contribute directly to a portable retirement account owned and controlled by the employee. The amount the employee accumulates during her entire career becomes the pool of funds she will have available for retirement. Once the employee retires, neither the employer nor taxpayers have any future obligation to fund the worker’s retirement.

Today, nearly 85 percent of private-sector employees are enrolled in some form of DC plan. The public sector, by contrast, continues to rely largely on DB plans.

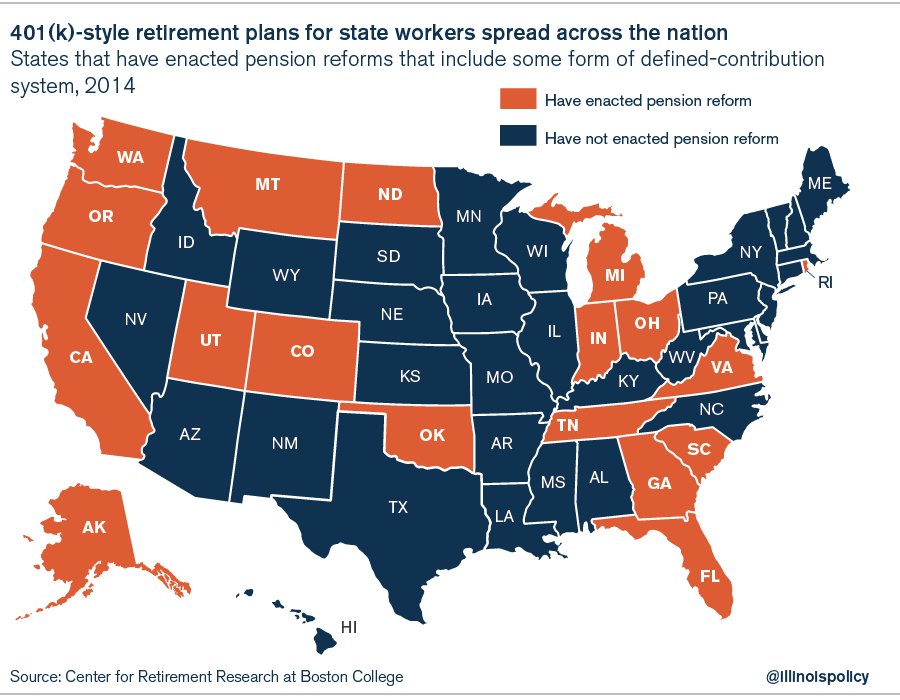

That said, more and more states, most recently Oklahoma, have moved their workers onto some form of a DC plan in an attempt to get their budgets under control and give workers more ownership over their retirements. Kentucky’s governor has also set his sights on 401(k)-style plans for new government workers.

Why Illinois has a pension crisis

Illinois’ massive, growing, government-worker pension debt is a direct result of three major factors: overgenerous pension benefits, political manipulation and inherent flaws of pension plans.

1. Politicians grant workers overly generous pension benefits that taxpayers can no longer afford.

Government workers who earn generous pension benefits have done nothing wrong. They’ve benefited from labor negotiations that have led to lucrative compensation packages. However, the state’s taxpayers can no longer afford to offer such benefits going forward.

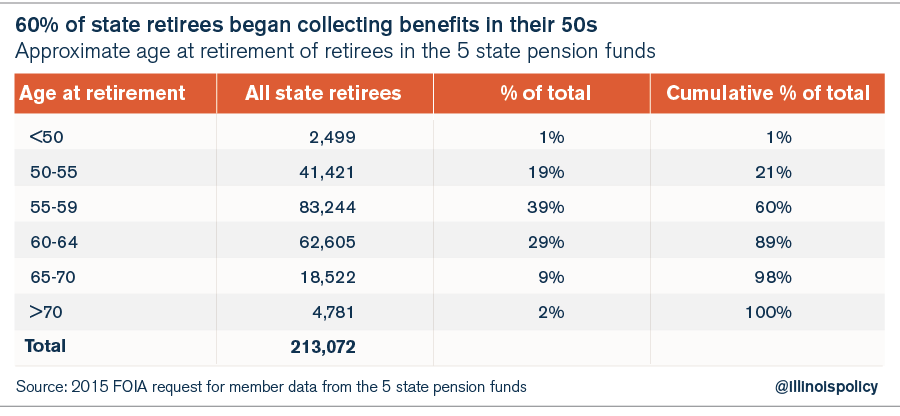

a. Retirement age: Private-sector workers cannot begin to collect full Social Security benefits until age 67. By contrast, 60 percent of state workers retire in their 50s, many of them with full benefits.

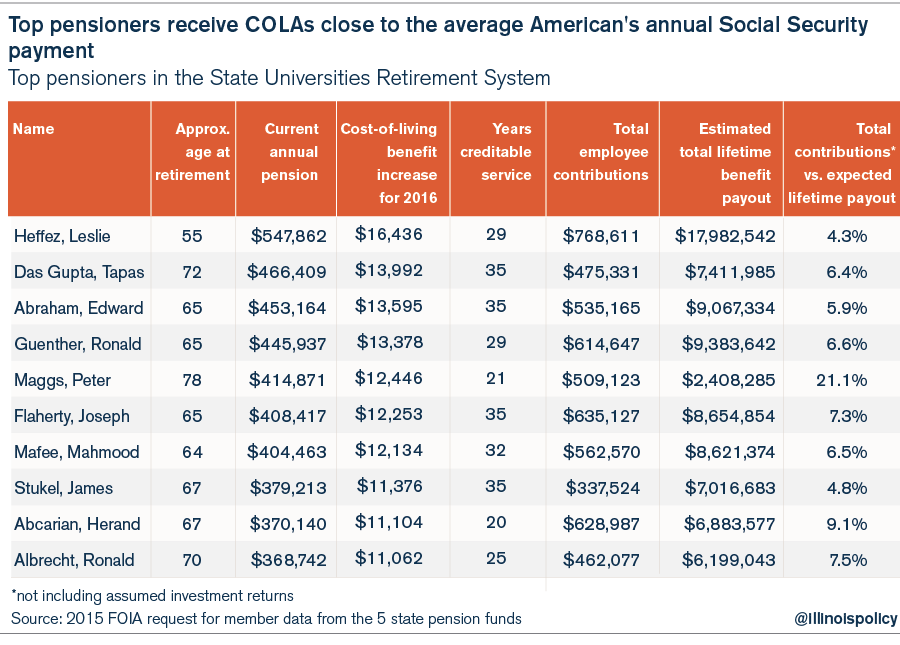

b. COLAs: Most retirees receive cost-of-living adjustments that are automatic, annual 3 percent compounded boosts to their pensions. That means their annual pension benefits will double in 25 years.

The state’s top pensioner, Leslie Heffez, earned a COLA of more than $16,000 in 2015, equal to the average annual Social Security payout for an average private-sector retiree. And since COLA benefits are not means-tested, Heffez will continue to receive COLA increases annually – which contributes mightily to his expected $18 million in lifetime pension benefits.

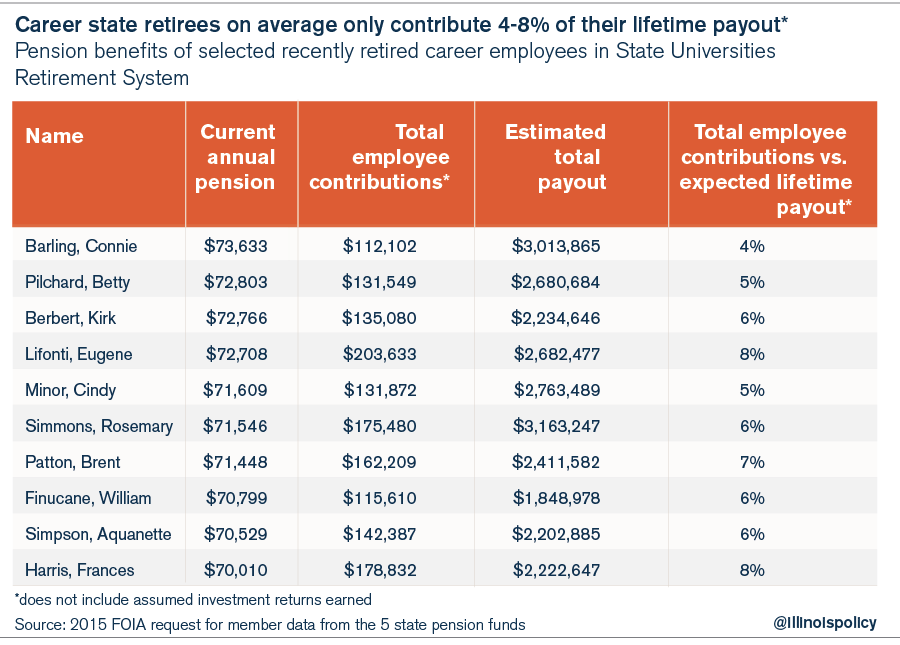

c. Contributions: Most retirees contribute only about 4 to 8 percent (8 to 16 percent when interest earned on investments is included) of what they receive in retirement benefits. For example, the average recently retired (from Jan. 1, 2013, through 2015) career (30 years of service) State Universities Retirement System member contributed only about $145,000 (6.5 percent) of the $2.2 million he or she will receive in lifetime retirement benefits.

d. Payouts: The average career (30 years of service) teacher who retired recently (within the last three years) receives a $71,000 pension and will collect over $2 million over the course of her retirement. To generate similar benefits, a worker in the private sector would need to have more than $1.5 million in her bank account when she retires.

In all, 53 percent of the over 213,000 state retirees in Illinois can expect to receive lifetime pension benefits of more than $1 million. Almost 40,000 (18 percent of all retirees) will receive $2 million or more in benefits. By contrast, private-sector workers with average Social Security benefits will only receive approximately $400,000 in lifetime benefits.

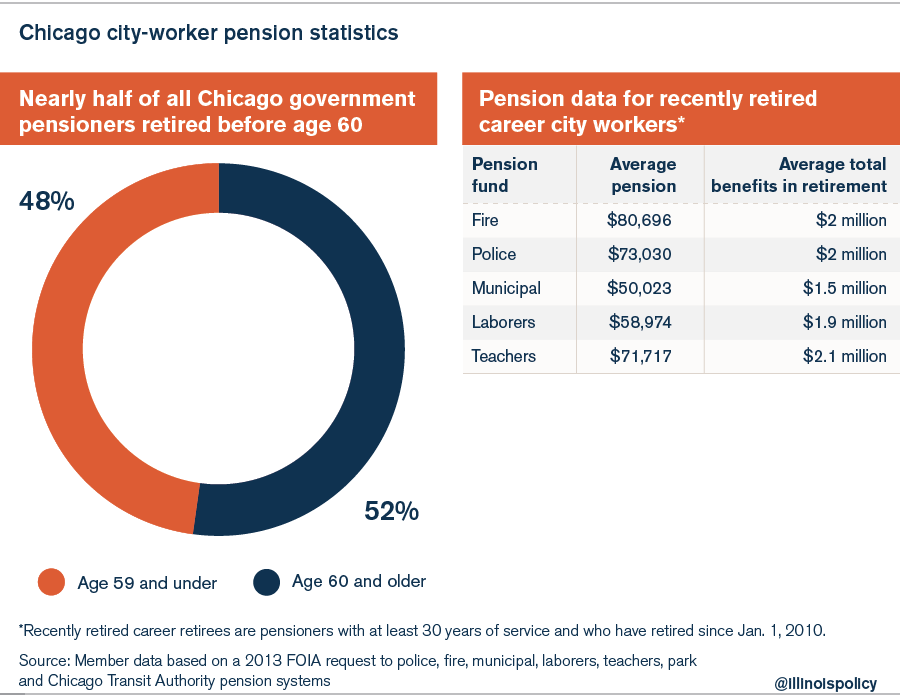

e. Benefits in Chicago: Employees for the city of Chicago also receive generous pension benefits. Nearly half of all city workers retire before age 60, and recently retired career workers (30 years of service or more) receive $65,000 average annual pensions.

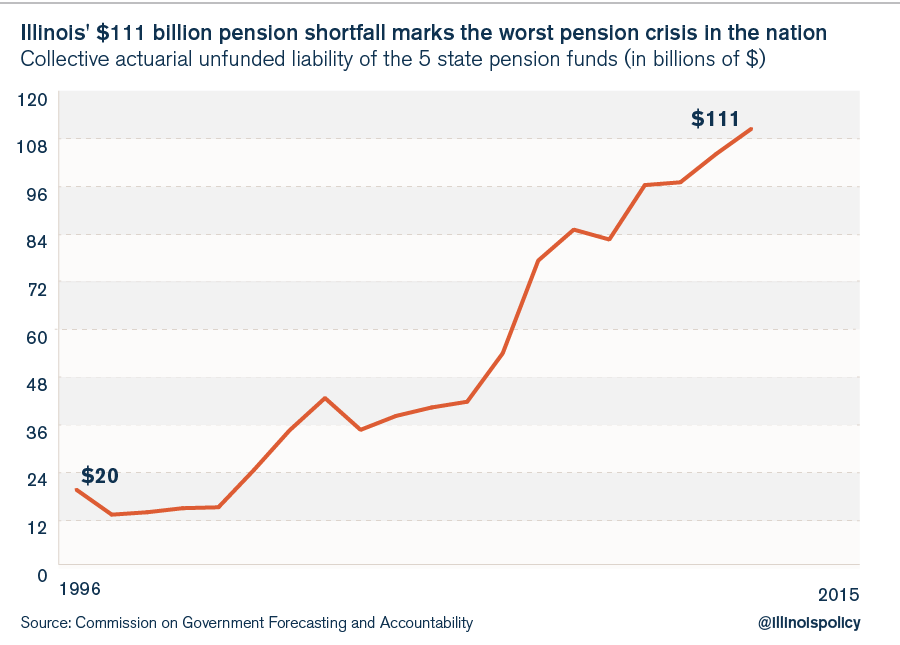

2. Politicians use pensions as a political slush fund. In 1994, Gov. Jim Edgar created a culture of kicking the can down the road when he enacted legislation that pushed state pension contributions far into the future – through 2045. Since then, Illinois politicians have borrowed, skipped payments and taxed to fund pensions rather than seek comprehensive reforms. As a result, the state’s 2015 pension shortfall has skyrocketed to $111 billion.

The current state of the Chicago teachers’ pension fund is the best example of how politicians manipulate pensions. Over the course of a decade, Chicago politicians redirected $3 billion in contributions away from the teachers’ pension fund, toward teachers’ salaries. Not only did this cause the teachers’ pension shortfall to skyrocket, but it also inflated teacher salaries, pushing teacher pension benefits to unaffordable levels.

The same thing also happened to Chicago’s police and firefighter pension funds. Police and firefighter salaries grew 50 to 70 percentage points faster than inflation over the past 30 years.

3. Pension plans are inherently flawed and unsustainable. Politicians’ failure to contribute to pensions is often blamed as the key reason Illinois pensions are so underfunded. However, that is not the case. A majority of the pension systems’ underfunding is due to the flaws inherent in DB plans. In DB plans, governments make promises to retirees based on certain assumptions – such as expected investment returns and mortality rates – which often fail. In all, 60 percent of the state’s current pension shortfall can be attributed to such failed assumptions.

The combination of these three factors has driven Illinois’ pension systems closer to insolvency. Chicago’s police and firefighters pension funds now have only a quarter of the money they need today to pay out future benefits. The Teachers’ Retirement System, the largest pension fund in the state, has less than half the money it needs. And at only 16 percent funded, the General Assembly’s own retirement system is the worst-off of all state funds, relying on a taxpayer bailout every year just to stay afloat.

Pensions and the Illinois budget

As Illinois’ pension funds fall farther into insolvency, the money needed to prop up the funds is growing far faster than Illinois’ budget. Pension costs already make up 25 percent of Illinois’ budget – a massive amount considering the average for other states is only 4 percent. Those costs have been crowding out funding for the state’s vital services.

For example, by 2025, the state will spend more of its education budget on teacher pensions than it will in the classroom. This will dramatically affect local school districts’ operational budgets – especially poorer districts with minority students that rely heavily on state funding.

Debunking pension myths

Despite the deepening pension crisis, defenders of the status quo – including government unions and many politicians – continue to argue against any reforms to the state’s pension systems.

Here are some of their favorite lines.

1. “Average pension benefits are modest.” The Chicago Teachers Union, for example, claims “the average Chicago Teachers’ Pension Fund (CTPF) retiree earns $42,000 per year.” But that’s a misleading number because the average includes short-term workers who receive relatively smaller pensions due to their limited time working for the government.

A more appropriate way to measure the full value of a pension plan is to look at the annual pensions of career (30-year) workers who recently retired. When measured that way, the average annual pension for a retired Chicago Public Schools career teacher is $71,717 – four times the average annual Social Security benefit that private-sector retirees receive ($16,000).

2. “Pension benefits are a promise.” Citing the Illinois Constitution’s pension-protection clause, which states that pensions may not be “diminished or impaired,” union officials say pension benefits for current government workers cannot be reformed – including, even, those benefits that have yet to be earned.

It’s true that already-earned pension benefits should be protected. However, the Illinois Policy Institute believes that it should be possible to reform the benefits that workers have yet to earn.

3. “Pensions need funding guarantees.” Supporters of the status quo also claim that Illinois’ pension systems need funding guarantees to ensure the plans receive their required contributions. They point to the only well-funded pension system in the state: the Illinois Municipal Retirement Fund, or IMRF. Under state law, local cities are mandated, through a court-enforced funding guarantee, to fund IMRF pensions before anything else.

But that arrangement – mandated contributions regardless of available city resources – has contributed to fiscal crises in municipalities across Illinois. Cities are forced to raise taxes and cut spending for road repair, libraries and police and firefighter pensions to make their mandated IMRF payments, crippling cities’ ability to deliver core services.

How to fix Illinois’ pension crisis

Moving from pensions to defined-contribution retirement plans for government workers is the only way to solve the state’s colossal pension woes. The Institute has long supported moving all government workers to 401(k)-style retirement plans. In 2013, members of the General Assembly proposed landmark bills that provided that government workers would be paid everything they’ve earned so far in the pension system and started a 401(k)-style system – modeled on the self-managed plans for state-university professors in which 18,000 employees are enrolled – for all benefits going forward.

Unfortunately, in May, the Illinois Supreme Court struck down Senate Bill 1 – a modest pension-reform law meant to bring some relief to Illinois’ fiscal crisis. The court ruled that the Illinois Constitution’s pension-protection clause protects both earned and unearned benefits of current state workers – ending any chance for significant pension reform involving current workers.

Since the Illinois Supreme Court’s ruling on SB1, debate over how to fix Illinois’ pension crisis has come to a screeching halt. Real, structural reforms to government-worker pension plans will need to wait until the Illinois Constitution can be amended to allow them – or until the state’s government-worker unions agree to pension changes at the bargaining table. However, that doesn’t mean the state is without remedies in the meantime.

Here is a list of what Illinois lawmakers can do immediately to address the state’s growing pension shortfall:

- Ditch politician pensions. With no unions to oppose reforms, Illinois politicians should lead by example and transition their own pensions into self-managed plans such as 401(k)s.

- Offer 401(k)s for new workers. The Illinois Supreme Court’s ruling on SB1 doesn’t affect the retirement plans offered to new government workers. Illinois lawmakers should follow the lead of states across the country – from Michigan to Oklahoma to Alaska – and adopt self-managed plans for all new state and municipal workers.

- Offer optional 401(k)s to current employees. Government workers shouldn’t be trapped in insolvent, politician-run retirement plans over which they have no ownership.

- Require all teachers to make contributions toward their own pensions. In Illinois, most public-school teachers don’t pay the required 9.4 percent employee contributions toward their own pensions. Instead, many school districts pay, as a benefit, some or all of the teachers’ required payments.

- Get the state out of the business of managing local school-district pensions. School districts should be responsible for the true costs of their employees and should pay for their annual pension costs. Going forward, the annual benefits accrued each year by teachers should be paid for by local school districts and not the state.

- Limit the growth of pensionable salaries. Government-worker pension benefits are growing at a pace that far exceeds the growth of taxpayers’ ability to fund them. With no way to structurally reform pension benefits for current government workers, the General Assembly’s only lever is to limit salary growth and other items that drive up pensionable salaries.

- Allow municipal bankruptcy. Without the ability to reform pensions for existing workers, local governments should have more control over how they operate. That means having the option to file for bankruptcy. Bankruptcy should be the option of last resort, but it can help struggling municipalities restructure their debt, renegotiate contracts and reform pensions.

The need for real reform

Illinois’ growing pension crises at both the state and municipal levels cannot be solved by burdening taxpayers with massive, ever-escalating taxes to bail out a system that is simply not sustainable.

Without real reforms, many pension systems across the state may become insolvent despite taxpayer bailouts, ruining the retirement security of hundreds of thousands of retired government workers.

However, the problem is not insurmountable. Solutions such as the seven reforms above would reduce the severity of the pension crisis and pave the way for bigger reforms.

Ultimately, the Illinois Constitution will have to be amended so the state can enact real reforms that realign the retirement benefits of government workers with what Illinois taxpayers can afford.