Budget gimmicks explained: Why the new Illinois spending plan is not balanced

Lawmakers claiming to have passed a balanced budget are relying on a number of common, but deceptive, budget maneuvers.

Illinois lawmakers on both sides of the aisle are claiming they passed a balanced budget for the upcoming fiscal year 2019. An Illinois Policy Institute analysis found that the budget was unbalanced by as much as $1.5 billion based on realistic revenue assumptions.

What explains the difference? Smoke and mirrors.

To make the budget appear balanced on paper, lawmakers are relying on a number of common budgetary gimmicks that don’t actually lead to balance. These gimmicks account for the fact that despite a constitutional balanced budget requirement, Illinois has not had a truly balanced budget since at least 2001.

Speculative pension savings

The spending plan relies on more than $444 million in pension savings. As much as $422 million of that amount is speculative and unlikely to materialize.

Most of the supposed savings come from two completely voluntary “pension buyouts.” First, vested but inactive Tier 1 pensioners – meaning employees hired before 2011 – are given the option of receiving 60 percent of the net present value of their pension annuity in a lump sum payment. Lawmakers claim this will save $41 million.

Second, the largest portion of the expected savings – $381.9 million – comes from an optional cost of living adjustment, or COLA, buyout. This would give Tier 1 members the option to trade their 3 percent compounding increases for a 1.5 percent simple annual increase, in exchange for an immediate payment of 70 percent of the net value of their future increases under the higher formula.

Lawmakers plan to issue up to $1 billion in bonds to pay for those buyouts now, since they don’t have the money on hand. The state previously borrowed $17.2 billion to make pension payments, which will cost $25.8 billion to pay off in the long run.

The problem? Lawmakers are essentially counting on state workers to voluntarily cut their own pensions.

According to state Rep. Mark Batinick, R-Plainfield, the savings are calculated using a 22 percent uptake rate on the pension buyouts, which is the same uptake rate as a similar plan passed in Missouri. Unfortunately, the situation in Missouri is very different from the situation in Illinois. Illinois’ Supreme Court has declared that the pension protection clause protects not only earned benefits, but future increases in those benefits as well. Missouri does not operate under this restriction.

Some pensioners may see the writing on the wall and decide that they want to take their retirement security out of the hands of politicians, in case the pension system goes insolvent. However, many state workers may also be unwilling to give up a constitutionally guaranteed benefit increase for a much smaller guaranteed payment now. That makes the Missouri uptake rate unrealistic for Illinois.

If significantly fewer Illinois workers accept the buyout options than expected, lawmakers will have a hole in the budget that could amount to hundreds of millions of dollars.

Ignoring known costs

Illinois state workers represented by the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees, or AFSCME, currently do not have a contract with the state. The last contract expired on June 30, 2015. Gov. Bruce Rauner and AFSCME have not been able to agree on a number of costly requests the union is making.

Despite being without a contract, courts have ordered the Rauner administration to pay the raises union workers would have received under the last contract. According to Wirepoints, this could cost as much as $400 million.

The state did not account for these costs in its recent spending plan. That means the state has as much as a $400 million liability, that it should be fully aware it needs to pay, not accounted for in the budget.

Illinois families cannot balance their budgets on paper by simply ignoring their rent. Whether they want to admit it or not, it’s part of their budget.

Selling the same building three times

Lawmakers are counting on the sale of the James R. Thompson Center to generate roughly $300 million in revenue this year.

In fact, they’ve been including that expected revenue in their budgets for three years running now. The building still has not been sold and no potential buyer has been made public. Former Gov. Rod Blagojevich also tried and failed to sell the building, according to the Chicago Tribune.

Deferred maintenance costs for the building are over $326 million and some real estate professionals doubt the $300 million price tag is even realistic.

Fund sweeps

The spending plan also relies on sweeping around $800 million from other state funds. This is an all too common gimmick that lawmakers use as a crutch to avoid spending within their means.

The Volcker Alliance has noted, “A basic tenet of budgeting is that one-time revenues should fund only one-time expenditures and that recurring revenues should cover obligations that come due every year.” Spending on the operating budget should be entirely financed through annual recurring revenues, primarily meaning taxes, not one-time revenue infusions.

Unfortunately, due to Illinois policymakers’ inability to control spending, the state has a habit of sweeping funds intended for dedicated purposes and issuing bonds to pay for pensions or operating costs.

Lawmakers have transferred money out of the budget stabilization fund every year since 2003. In all but five of the last 15 years, the state has either borrowed from state funds, issued bonds, or swept funds to pay for operations. The difference between a fund sweep and borrowing from a fund is that sweeps do not have to be paid back. However, the state often “forgives” its borrowing from special funds and decides not to pay them back anyway.

According to Truth in Accounting, Illinois has over 600 special funds. Special funds often have dedicated revenue sources apart from the general funds budget, such has user fees, licensing fees or regulatory penalties. While not all of these funds are well managed or necessary, many are self-funding and productive.

For example, the State Crime Laboratory fund is financed by fees collected by circuit courts for criminal laboratory analysis performed by the Illinois State Police. The funds are supposed to be used only for expenses of state crime laboratories. The General Assembly swept over $150,000 out of this fund in fiscal year 2018.

In addition to putting off tough choices about spending reductions, fund sweeps and borrowing are two reasons Illinois fails on financial transparency – these practices hide the real cost of government from residents and mislead bondholders about the sustainability of spending.

The Illinois Policy Institute supports a proposed constitutional amendment filed this year that would end the practice of relying on fund sweeps and short term borrowing as “revenue” for the annual budget.

Phony accounting practices

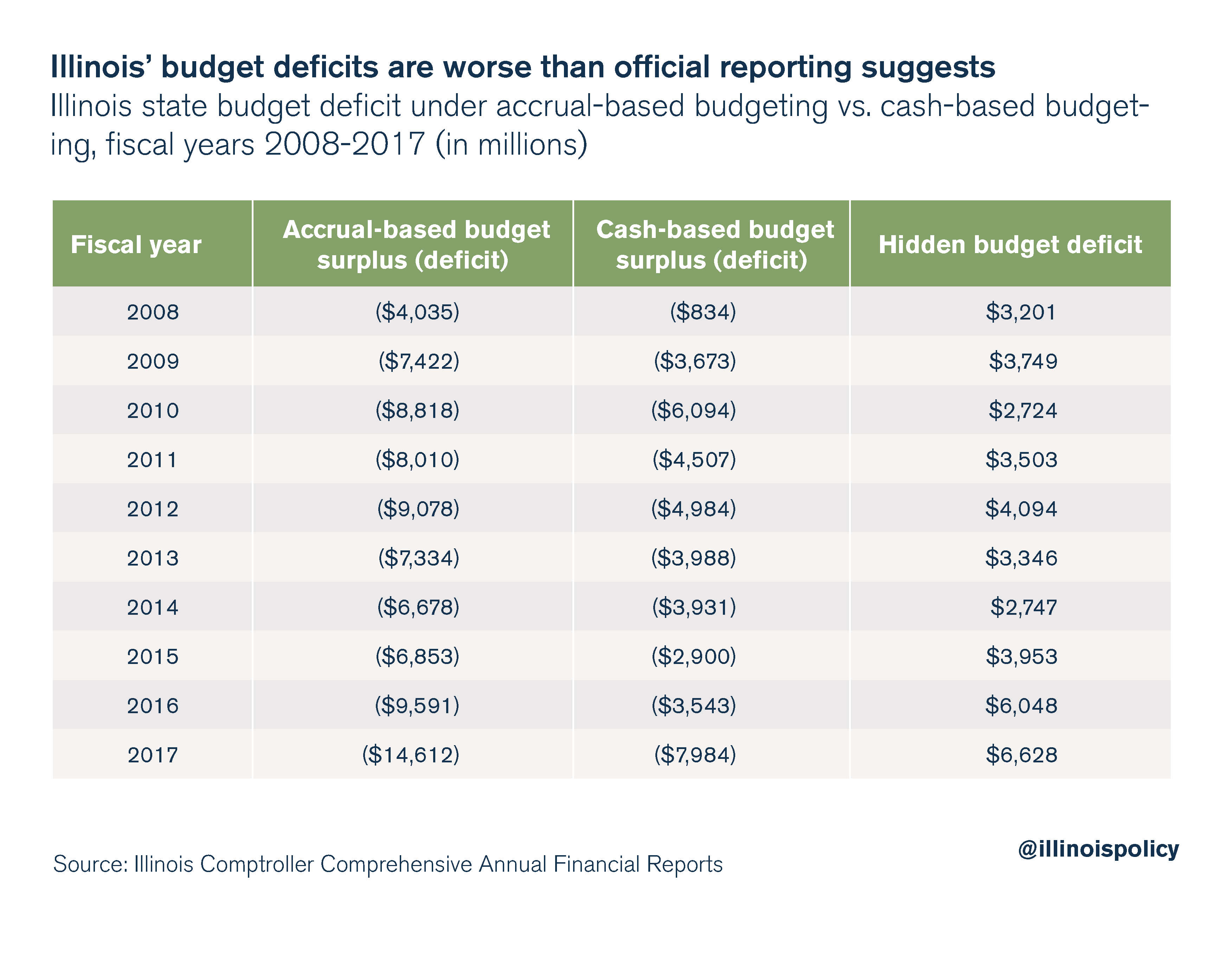

Another long-running budget gimmick in Illinois is the use of cash-based budgeting. Under this system, revenues are counted in the year they are received. Meanwhile, expenses are counted only in the year they are paid, not the year they are incurred. Imagine if a household magically “balanced” its budget each month by not paying the electric bill. That’s the type of behavior cash-based budgeting hides in state government.

The extent to which this accounting gimmick hides the true cost of Illinois government spending can be seen by comparing Illinois’ cash-based accounting to a system using generally accepted accounting principles, or GAAP. The crucial difference between these two methods is that GAAP includes what’s called “accrual-based” accounting.

When comparing cash-based accounting to accrual-based accounting, it’s clear the state has underreported its true budget deficit by billions of dollars each year. The true budget deficit for fiscal year 2017 alone was at least $6.6 billion worse than official reporting, and lawmakers’ assumptions, suggest.

In addition to the traditional reporting lawmakers use when planning the budget each year, the Illinois comptroller releases a Comprehensive Annual Financial Report, or CAFR, which uses accrual-based accounting. The problem is that the CAFR doesn’t come out until months after the fiscal year ends, making it useless for the budget planning process.

Due to the many other gimmicks in the spending plan, the CAFR that comes out after the end of fiscal year 2019 is likely to show a worsening of Illinois’ net fiscal position.

A better path forward

The same day lawmakers were declaring victory and calling their bipartisan negotiations a “love fest”, Moody’s Investors Service warned that the state needs to address its pension liabilities and unfunded bill backlog sooner rather than later. “A failure to adopt mitigating strategies soon will greatly increase the state’s risk that these rising costs will become unaffordable without severe public service cuts,” the report stated.

The recent spending plan does nothing to address the long-term challenges facing Illinois. If any of the speculative financial assumptions made by lawmakers fail to result in expected savings or revenues, the state’s challenges will be even more difficult to deal with next year.

Illinois lawmakers have already proven they cannot exercise fiscal restraint on their own and have skirted the existing balanced budget requirement in the state constitution. To fix this problem, Illinois should adopt a spending cap amendment to the Illinois Constitution that ties lawmakers’ ability to spend money to taxpayers’ ability to pay for it.

A spending cap is a commonsense solution that received bipartisan support in the General Assembly this year. Proposed amendments would cap annual increases in general funds spending to the 10-year average growth rate in the state’s per capita GDP. While it is too late for constitutional amendments to save this year’s budget, lawmakers can always voluntarily adopt a spending cap as a budgeting principle. In the long run, a spending cap could help the state get out of debt, build a rainy day fund to save for recessions and eventually cut taxes.