Illinois’ economic turnaround depends on entrepreneurship

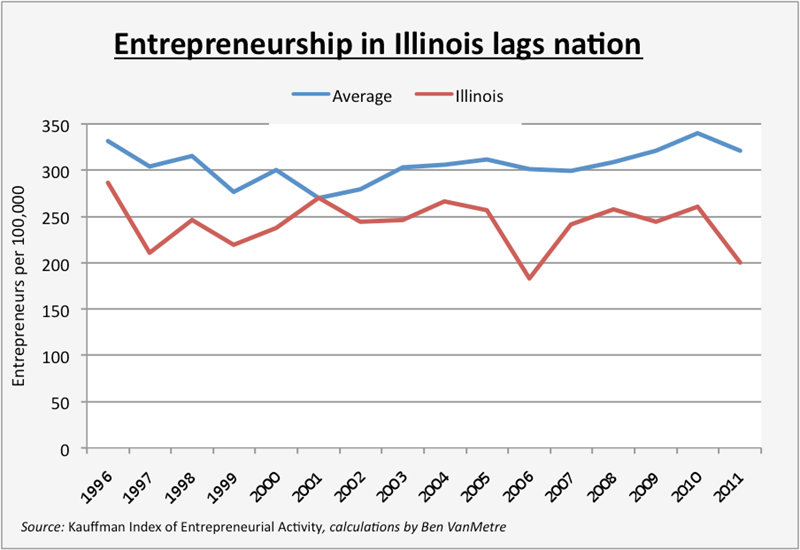

As the graphic shows, the rate of entrepreneurship in Illinois has been below the national average every year since 1996 except for 2001. The Kauffman Foundation entrepreneurship index measures the percentage of adults ages 20 to 64 that start a new business each month and work 15 or more hours per week. It’s measured across all 50...

As the graphic shows, the rate of entrepreneurship in Illinois has been below the national average every year since 1996 except for 2001. The Kauffman Foundation entrepreneurship index measures the percentage of adults ages 20 to 64 that start a new business each month and work 15 or more hours per week. It’s measured across all 50 states. New business startups are key to Illinois’ economic turnaround.

Net business births are the greatest drivers of net job growth in Illinois, according to a forthcoming study by the Illinois Policy Institute. Business startups have more of an impact on adding new jobs than businesses moving to Illinois or existing companies in the state expanding.

Bottom line: if we want to get people back to work in Illinois, we must make Illinois a place where entrepreneurs want to start a lot of new businesses. Rapid business creation translates into a dynamic economy with lots of new job opportunities.

How do we make Illinois a destination spot for entrepreneurs?

Economists have long recognized the connection between entrepreneurship and economic prosperity. Entrepreneurs are the engines of the market economy by providing new jobs, products and services. Because of this, some state and local governments enact policies they think will encourage entrepreneurship, including such typical measures as providing venture capital funding and other items required by new businesses.

Economists Steven Kreft and Russell Sobel have turned this conventional analysis on its head. Using U.S. state-level data, they apply statistical tests to demonstrate that it is entrepreneurial activity—measured by new sole proprietorships and patents for new products—that leads to venture capital investment, rather than vice versa. In other words, Kreft and Sobel find that if a state has entrepreneurs, venture capital will come to them without extra prodding from policy makers and discriminatory government subsidies or loans.

Kreft and Sobel next turn to the obvious question of how a state can attract or inculcate entrepreneurship, and their answer is “economic freedom.” Even after accounting for other factors such as a state’s unemployment rate, percentage of college-educated workforce and so on, Kreft and Sobel find that a state’s level of economic freedom has a significant impact on its growth rate of sole proprietorships.

The conclusion is that states do not need to spend tax dollars on venture funds to stimulate new businesses. On the contrary, a state need only provide the basic framework of economic freedom, and entrepreneurs will thrive naturally, attracting investment in the process.

How is Illinois doing in encouraging economic freedom to lure entrepreneurs and venture capital? Bottom line: not good. In the second quarter of 2012, private venture capital investment in Illinois companies dropped 19 percent from the same period last year, according to Dow Jones VentureSource. Illinois is attracting a shrinking percentage of venture capital nationally.

And now Gov. Pat Quinn wants to impose a progressive income tax in Illinois. This would further punish success, weaken economic freedom and drive more entrepreneurs out of Illinois.

Quinn just doesn’t get it.

A better approach is to abolish Illinois’ income tax and let entrepreneurs keep the fruits of their labor to re-invest in themselves and their businesses, sparking job creation.