False promises, real harm: Why Illinoisans should reject a progressive income tax

By Orphe Divounguy, Bryce Hill, Joe Tabor

Download Report

False promises, real harm: Why Illinoisans should reject a progressive income tax

By Orphe Divounguy, Bryce Hill, Joe Tabor

Download Report

With Illinoisans already shouldering a record $5 billion income tax hike passed in 2017 – which still could not keep up with Springfield’s spending demands – many state lawmakers are trying to justify further tax hikes without drawing the ire of the voting public.

How? By calling for a progressive income tax. Some members of the Illinois General Assembly, as well as many Democratic gubernatorial candidates, have been pushing the idea of scrapping Illinois’ constitutionally protected flat income tax in favor of a progressive income tax that would make “the rich” pay their “fair share.”

Proponents of scrapping this constitutional protection make three key claims regarding a progressive income tax: it would reduce taxes on the middle class, it would go a long way toward reducing income inequality and it would benefit the state’s economy.

An evaluation of current progressive tax proposals in the Illinois General Assembly, economic literature on progressive income taxes and outcomes in all 50 states reveal these claims are misleading at best.

First, states with progressive income taxes have seen slower economic growth and faster growth in inequality.

Second, most economists agree that more progressive tax structures reduce economic growth.

And finally, Illinois’ spending problems dictate that a progressive tax would entail large tax hikes on the middle class, leading to severe economic damage. A leading progressive tax proposal in the Illinois General Assembly – House Bill 3522 – would hike income taxes for a vast majority of Illinoisans. Economic modeling estimates that if this proposal had been enacted in 2016, it would have cost Illinoisans 34,500 jobs and cost the state economy $5.5 billion in the first year after enacted, erasing nearly 75 percent of the employment growth Illinois saw in 2017.

This potential economic harm is the most important reason Illinoisans should not allow a progressive income tax. It would likely lead to tax hikes on the middle class, fewer job prospects and lower incomes.

In short, a progressive tax is not the solution Illinoisans need to turn their state around.

Instead, lawmakers must look to rein in the growth in state spending, which outpaced personal income growth by 25 percent from 2005-2015. This lack of discipline has forced tax hikes, unsustainable debt and enormous uncertainty in the private sector over the future of Illinois. Rather than introducing more uncertainty with a progressive income tax system, lawmakers should adopt a spending cap that ties state spending growth to growth in Illinois’ economy. Illinoisans can then rest assured they’re getting a state government they can afford.

Introduction

With Illinoisans already shouldering a record $5 billion income tax hike passed in 2017, which still could not keep up with Springfield’s spending demands, many state lawmakers are trying to justify even further tax hikes on Illinoisans without inciting the rage of taxpayers. They are doing this by calling for a progressive income tax.

Currently, the Illinois Constitution mandates that state income taxes remain at a single, flat rate. Amending the constitution requires a three-fifths vote of the Illinois House and Senate, and that amendment would also have to be approved by voters in one of two ways in the next election. The first method is through a majority vote of all voters in the election (for example, if 1 million Illinoisans vote in the election, 500,001 would need to vote in support of the amendment for it to pass). The second method is through a three-fifths majority of those voting specifically on the referendum question (of those 1 million total voters, if only 500,000 voted on the referendum question, it would require 300,000 votes to pass). Constitutional amendments do not require the governor’s signature.

Under a progressive income tax system, taxpayers pay increasingly higher tax rates the more they earn. In other words, low-income earners would pay the smallest share of their income in taxes, while high-income earners would end up paying the highest share of their income in taxes.

Advocates of a progressive income tax at the state level make three key claims, all of which are misleading to varying degrees:

- A progressive income tax would reduce taxes on the middle class.

- A progressive income tax would go a long way toward reducing income inequality.

- A progressive income tax could actually benefit the state’s economy.

On the opposite side of the debate are those who believe the income tax rate should remain flat, as it is currently in Illinois. Proponents of the flat tax system pose three main arguments:

- A flat tax system is fairer because all taxpayers pay the same tax rate.

- Wealthier Illinoisans already pay the bulk of all income taxes collected in the state.

- A progressive income tax will do little to improve income equality while harming economic outcomes for all.

Since the publication of the seminal work of Hall and Rabushka (1995)1, academics have been arguing in favor of a simplification of the tax code, a broadening of the tax base and a reduction of marginal taxes. Progressive taxation does the opposite: it makes the tax code more complex and can have disastrous effects on economic growth.

The progressive tax and income inequality

Politicians frequently point to income inequality when arguing in favor of a progressive income tax. Despite good intentions, it is not clear from the evidence that progressive tax schemes are successful at reducing income inequality. In fact, states with a progressive income tax see greater income inequality, and have seen income inequality rise faster than states without a progressive income tax.

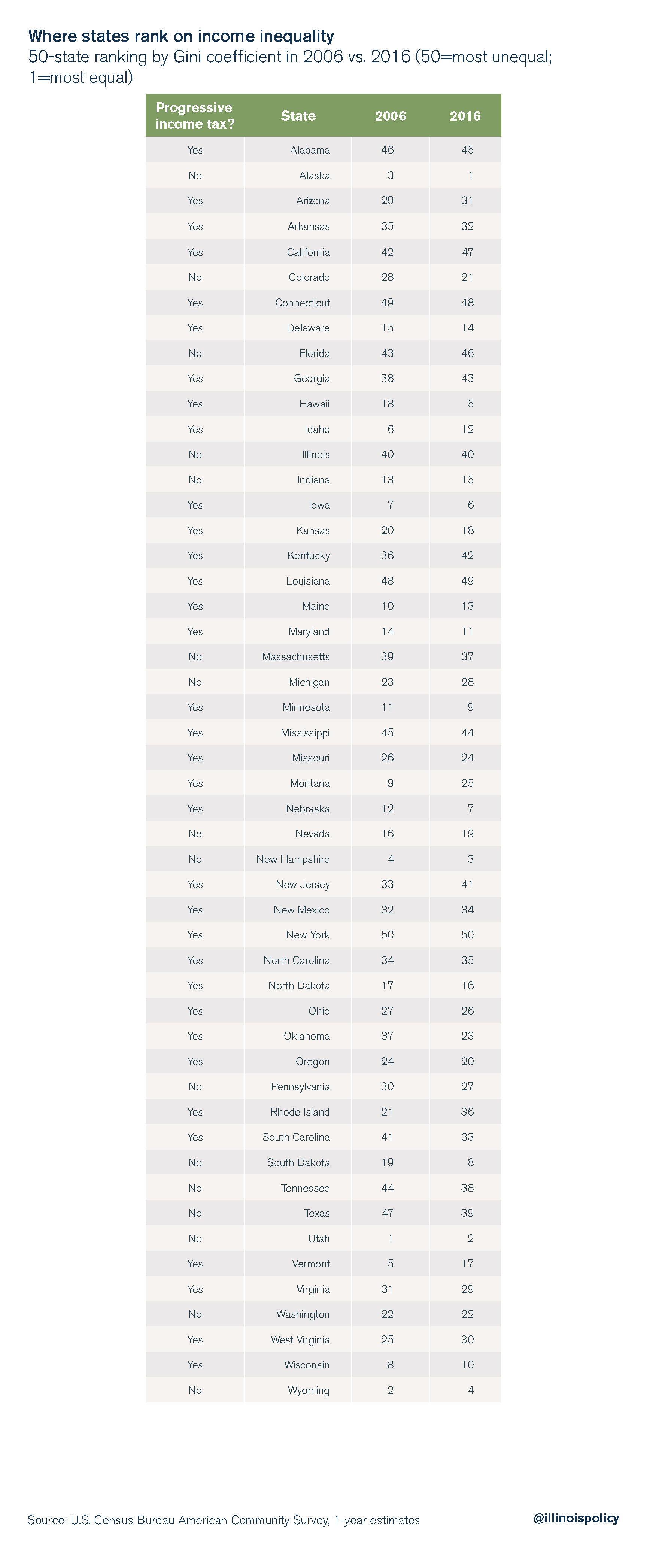

Although there are different ways to measure inequality, the most widely used measure is the Gini coefficient. The Gini coefficient of income measures the disparity in income between segments of the population. Lower Gini coefficients indicate a lower level of income inequality.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey, the five states in 2006 with the lowest Gini coefficients – meaning the lowest levels of income inequality – were Utah, Wyoming, Alaska, New Hampshire and Vermont. Only Vermont had a progressive income tax. In 2016, Alaska, Utah, New Hampshire, Wyoming and Hawaii had the lowest Gini coefficients. Only Hawaii has a progressive income tax.

By 2016, Vermont was more unequal, falling to 17th place from 5th place based on the Gini coefficient. Hawaii moved up the rankings to 5th place from 18th place between 2006 and 2016. Hawaii’s rise in the rankings was only due to rising inequality across the U.S.

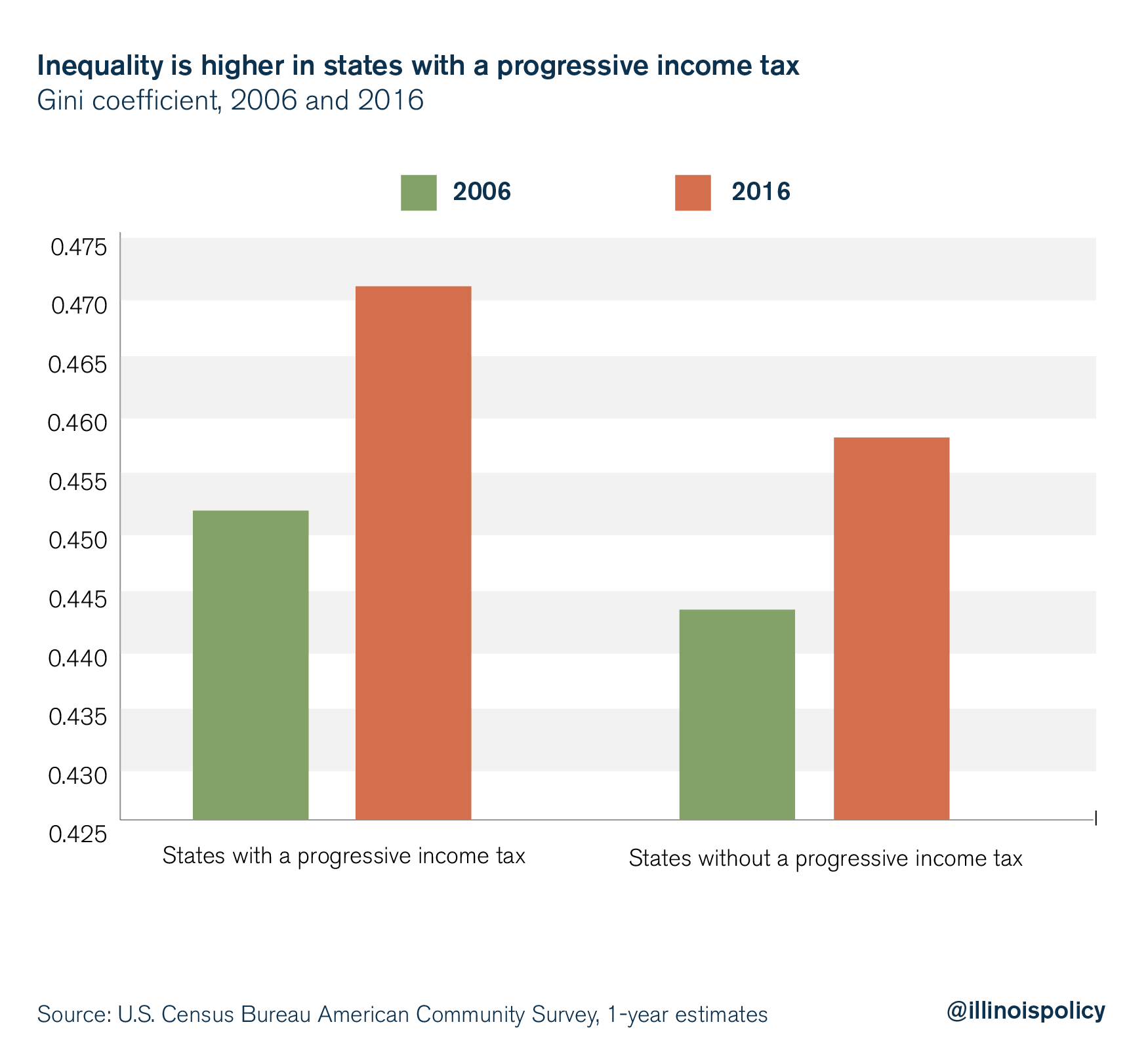

While changes in inequality reflect a host of factors, it is certainly not the case that states with a progressive income tax are more equal. In 2016, the average Gini coefficient in states with a progressive tax was 2.8 percent higher than states without a progressive income tax.

Not only is inequality higher in states with a progressive income tax, but inequality has risen faster in those states as well. Inequality in states with a progressive income tax grew 4.2 percent from 2006 to 2016, while inequality grew by 3.3 percent in states without a progressive income tax.

Would a progressive income tax reduce inequality in Illinois? Economists remain divided as to whether tax progressivity reduces inequality or has any effect on inequality whatsoever (see Appendix A).

The progressive tax and economic growth

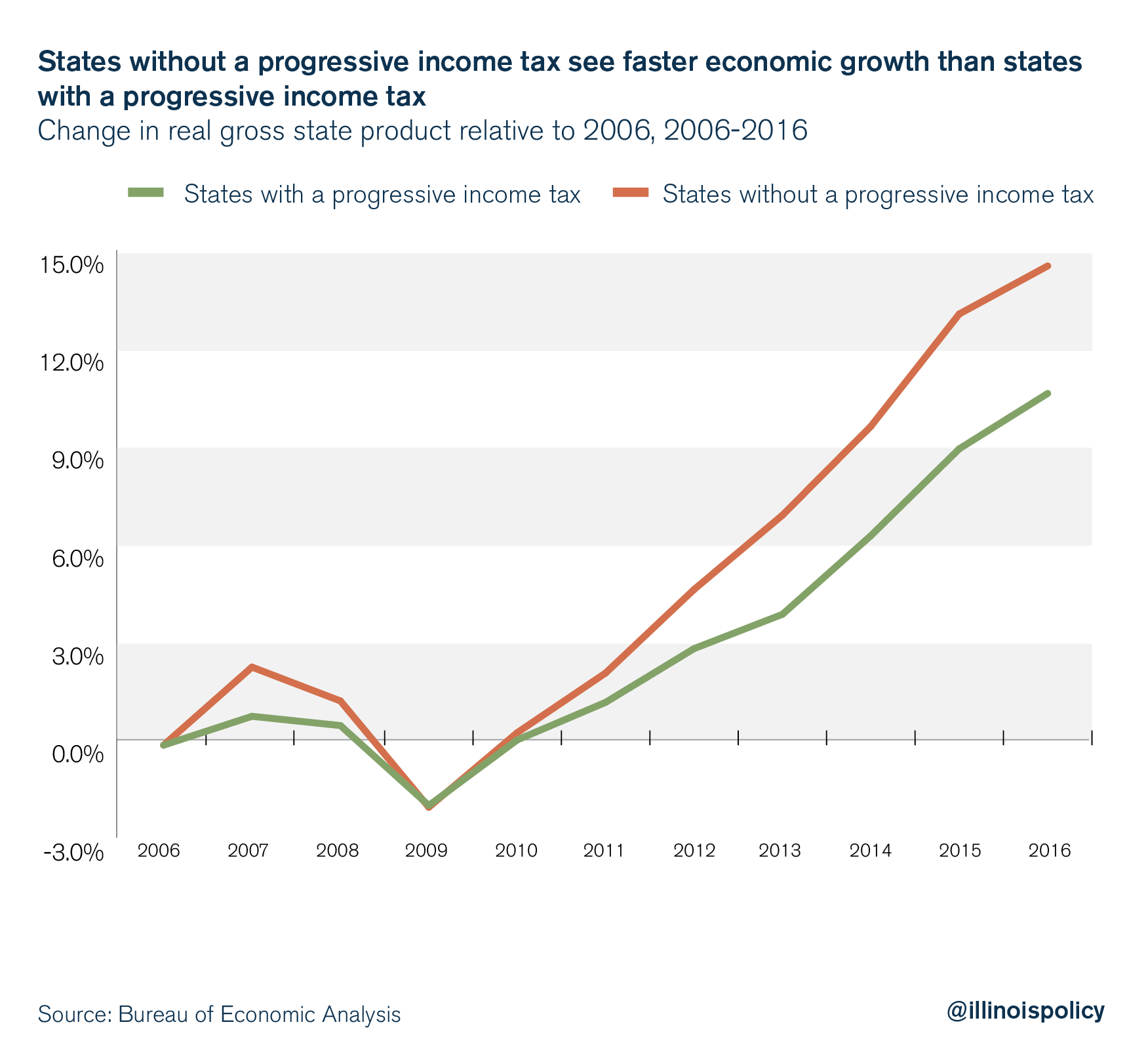

Although the academic literature hasn’t reached a definitive conclusion on the impact of progressive income taxation on inequality, most economists agree that more progressive tax structures reduce economic growth. And the data point to the same conclusion: States without a progressive income tax have performed better than states with a progressive income tax.

Examining the past decade of the most recently available macroeconomic data reveals overall economic activity – measured as real gross state product, or GSP – has grown faster in states without a progressive income tax than in states with a progressive income tax. Since 2006, states without a progressive income tax have seen GSP grow by 14.7 percent, while states with a progressive income tax have seen 10.8 percent GSP growth.

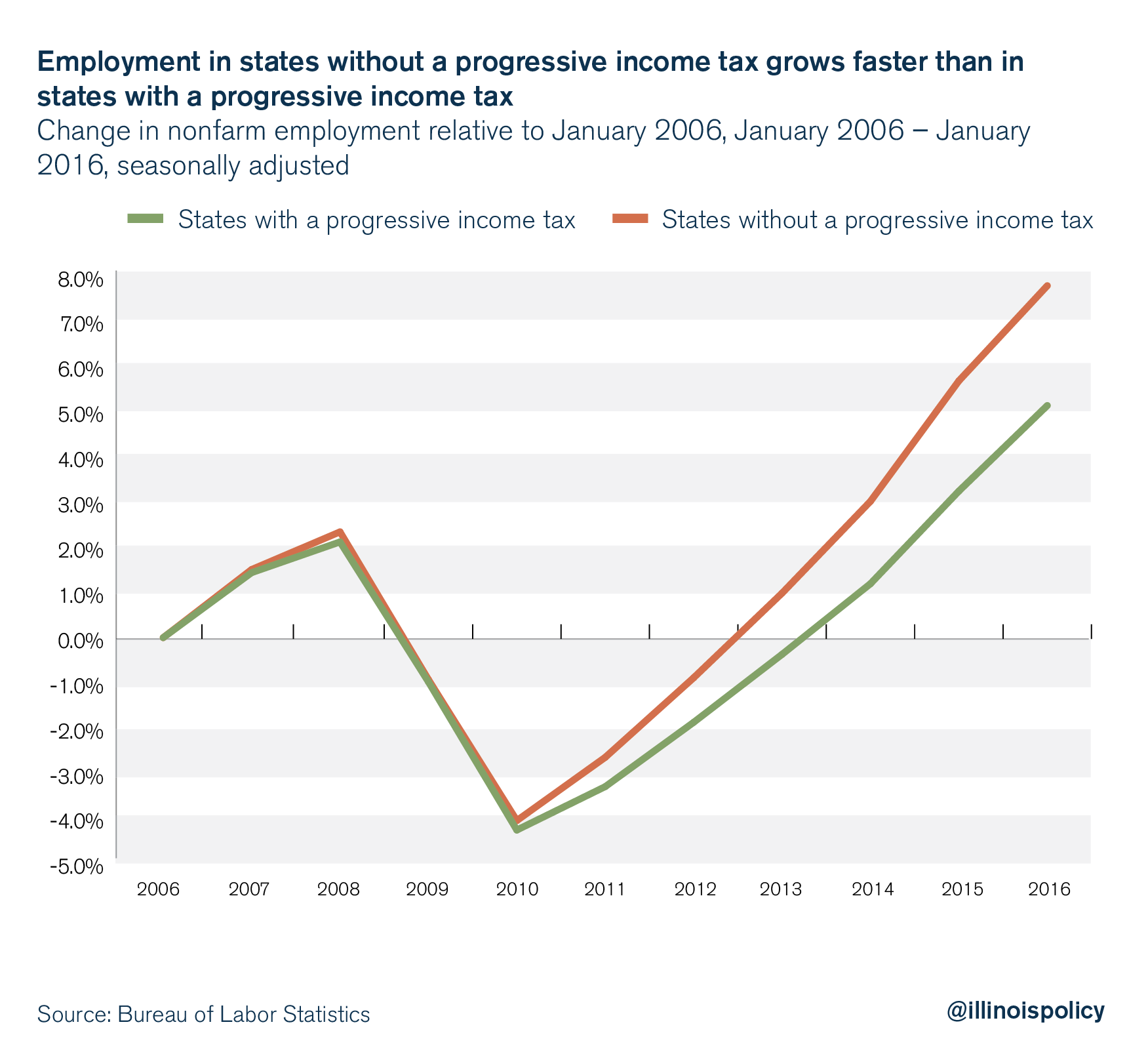

Additionally, employment has increased faster in states without progressive income taxes. In states without a progressive income tax, nonfarm payrolls have increased 7.8 percent, while payrolls have only increased 5.1 percent in states with a progressive income tax, since 2006.

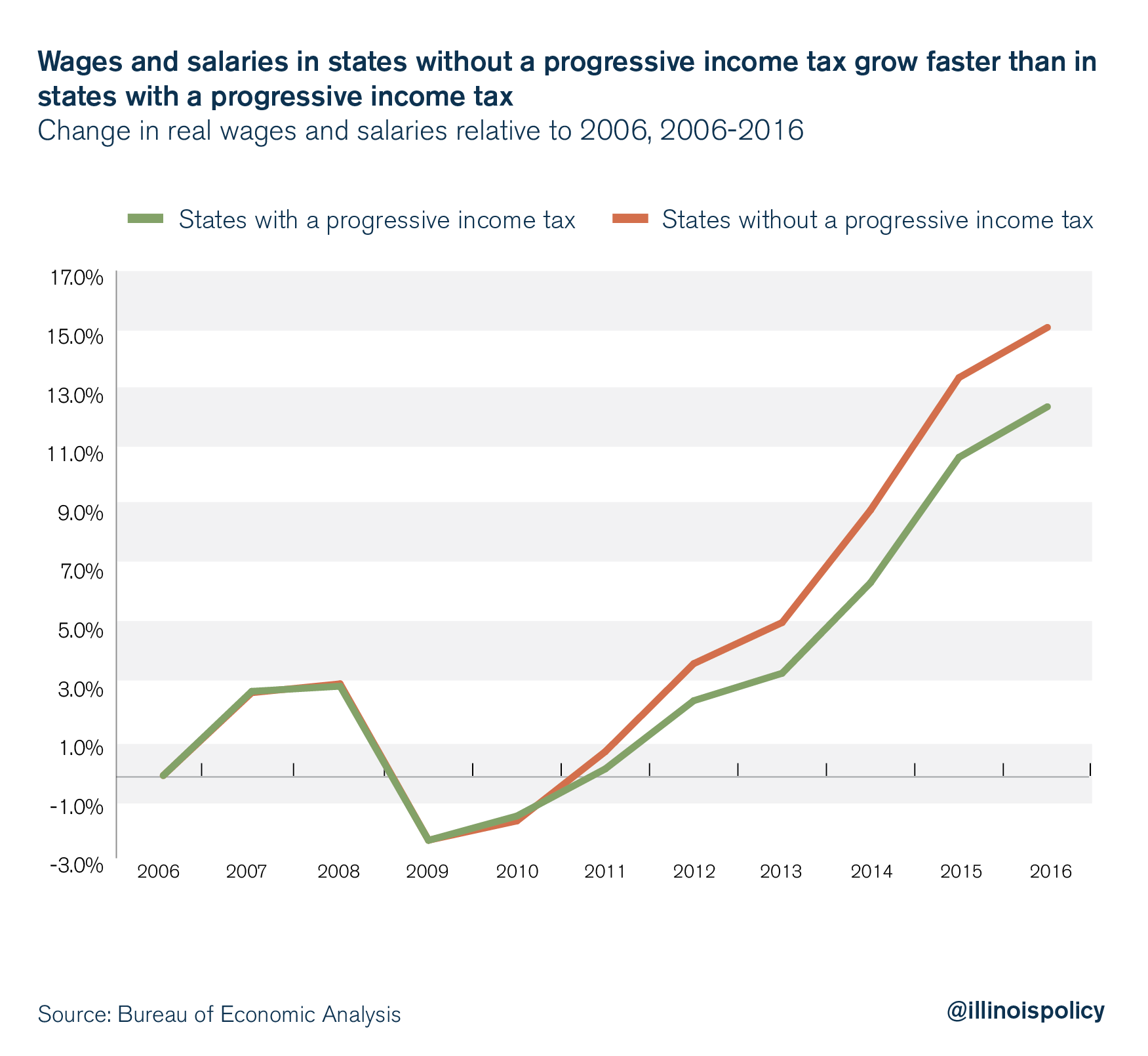

Wages and salaries have also been growing faster in states without a progressive income tax. Since 2006, states without a progressive income tax have seen wages and salaries increase 15.3 percent. Meanwhile, in states with a progressive income tax, wages and salaries have only increased 12.6 percent.

A majority of economists seem to agree that under plausible assumptions, tax progressivity has had a negative impact on the U.S. economy (see Appendix B).

The FRIENDLY Act and the harm of a progressive tax

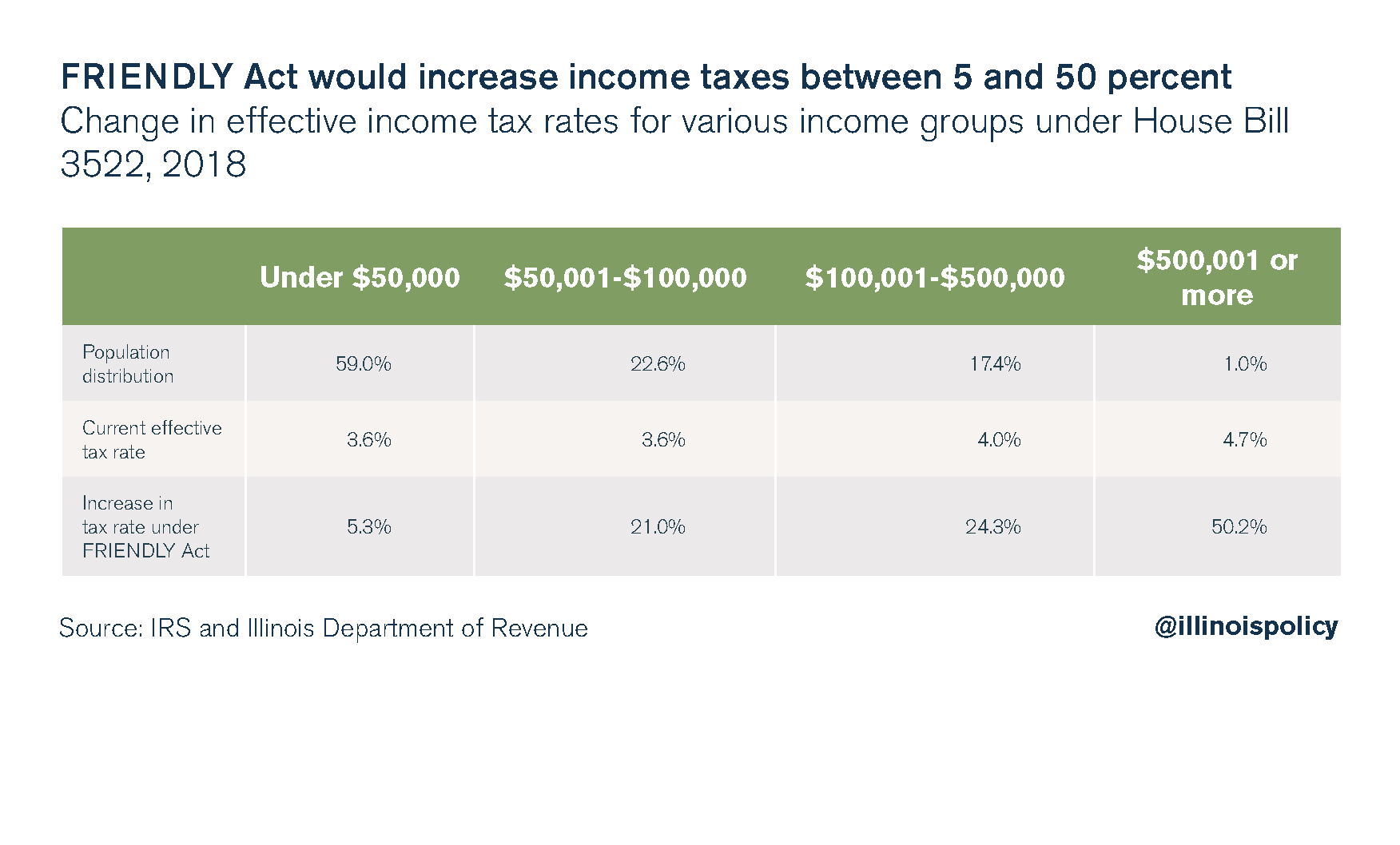

House Bill 3522, filed in the Illinois House of Representatives in 2017 by state Rep. Robert Martwick, D-Chicago, would set the tax rates for a progressive income tax. Also known as the FRIENDLY Act, this proposal would raise taxes on Illinoisans making as little as $17,300 a year by enacting the following income tax rates:

- 4 percent for income between $0-$7,500

- 5.84 percent for income between $7,501-$15,000

- 6.27 percent for income between $15,001-$225,000

- 7.65 percent for income above $225,000

These rates would cause an increase in income taxes for a vast majority of Illinoisans.

Measuring the effects of tax changes on the economy is a challenging task. Fortunately, there’s a large body of expert literature that addresses difficult empirical challenges and that proposes economic theories that are consistent with the data. Romer and Romer (2010) find that tax increases have a negative impact on real gross domestic product.2 This is because tax increases have a large and sustained negative impact on investment. These results are consistent with the findings of Blanchard and Perotti (2002)3 and Mountford and Uhlig (2009).4

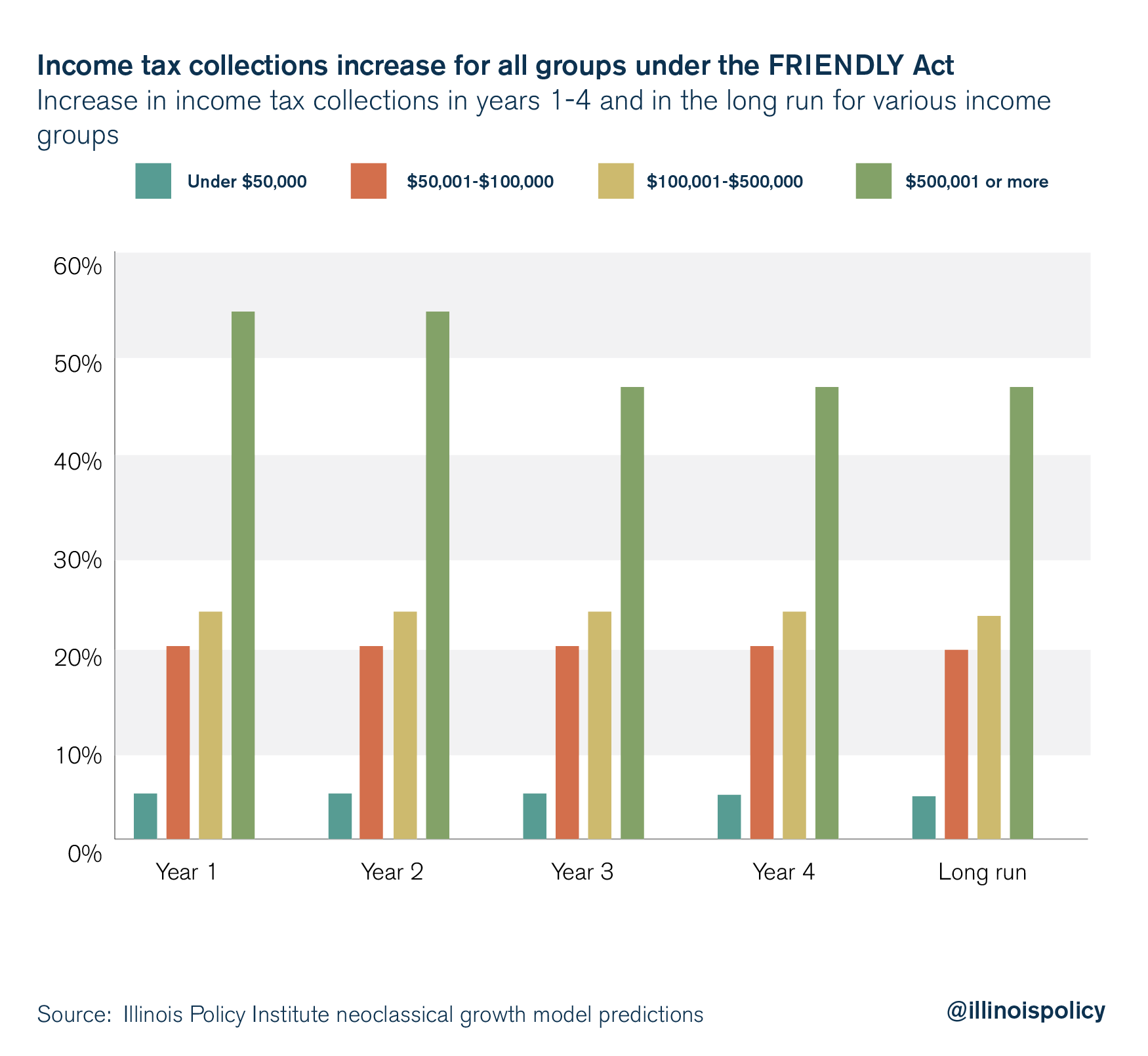

As expected, simulating Martwick’s progressive income tax in a dynamic macroeconomic model (see Appendix C and Appendix D) would raise additional income tax revenues, because most Illinoisans face a higher tax burden under this proposal.

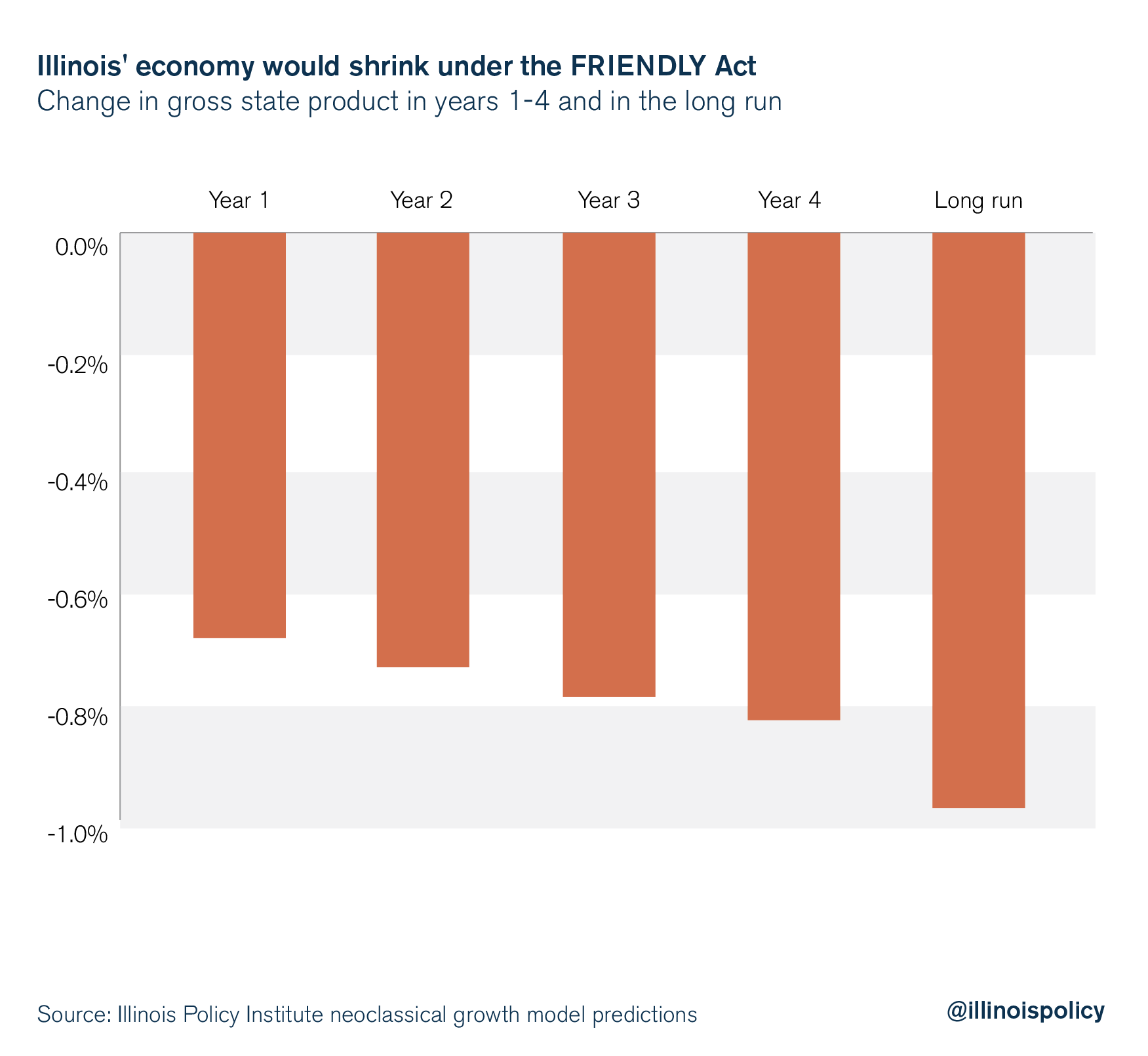

Simulating the proposed level of tax progressivity lowers aggregate economic activity. This is because the tax plan implies a tax hike that results in decreased aggregate investment. The increase in the tax burden has a negative impact on investment expenditures. When the marginal productivity of labor and capital decline, real wages fall.

If this policy had been enacted in 2016, Illinois’ economy would have shrunk by $5.5 billion in the first year alone.

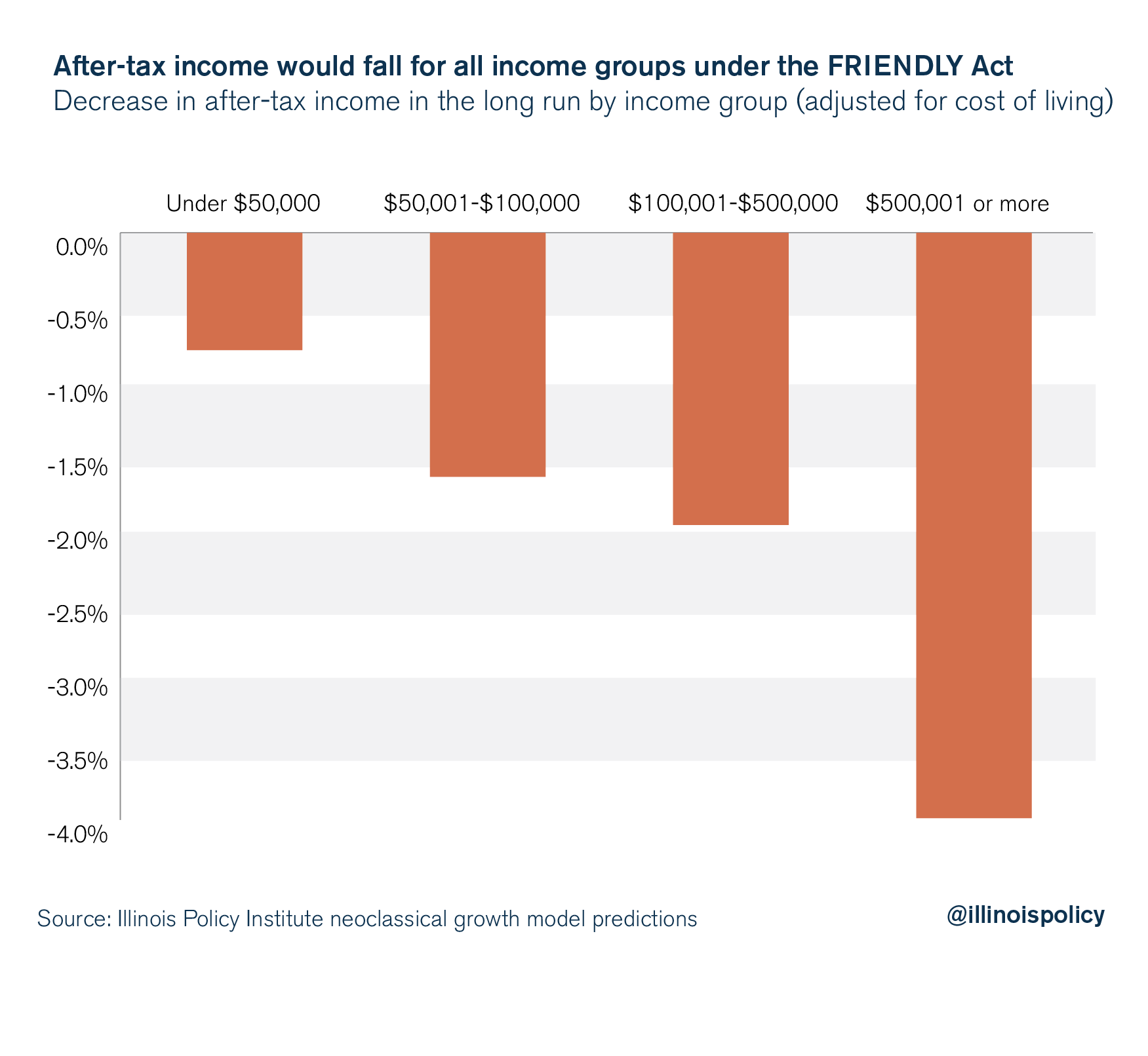

In the long term, Illinoisans would see reduced incomes as a result of the FRIENDLY Act. Adjusted for cost of living, after-tax incomes would drop 0.8 percent for the average income earner making less than $50,000; drop 1.6 percent for the average earner making between $50,001 and $100,000; drop 1.9 percent for the average earner making between $100,001 and $500,000; and drop 4.1 percent for the average earners making over $500,001.

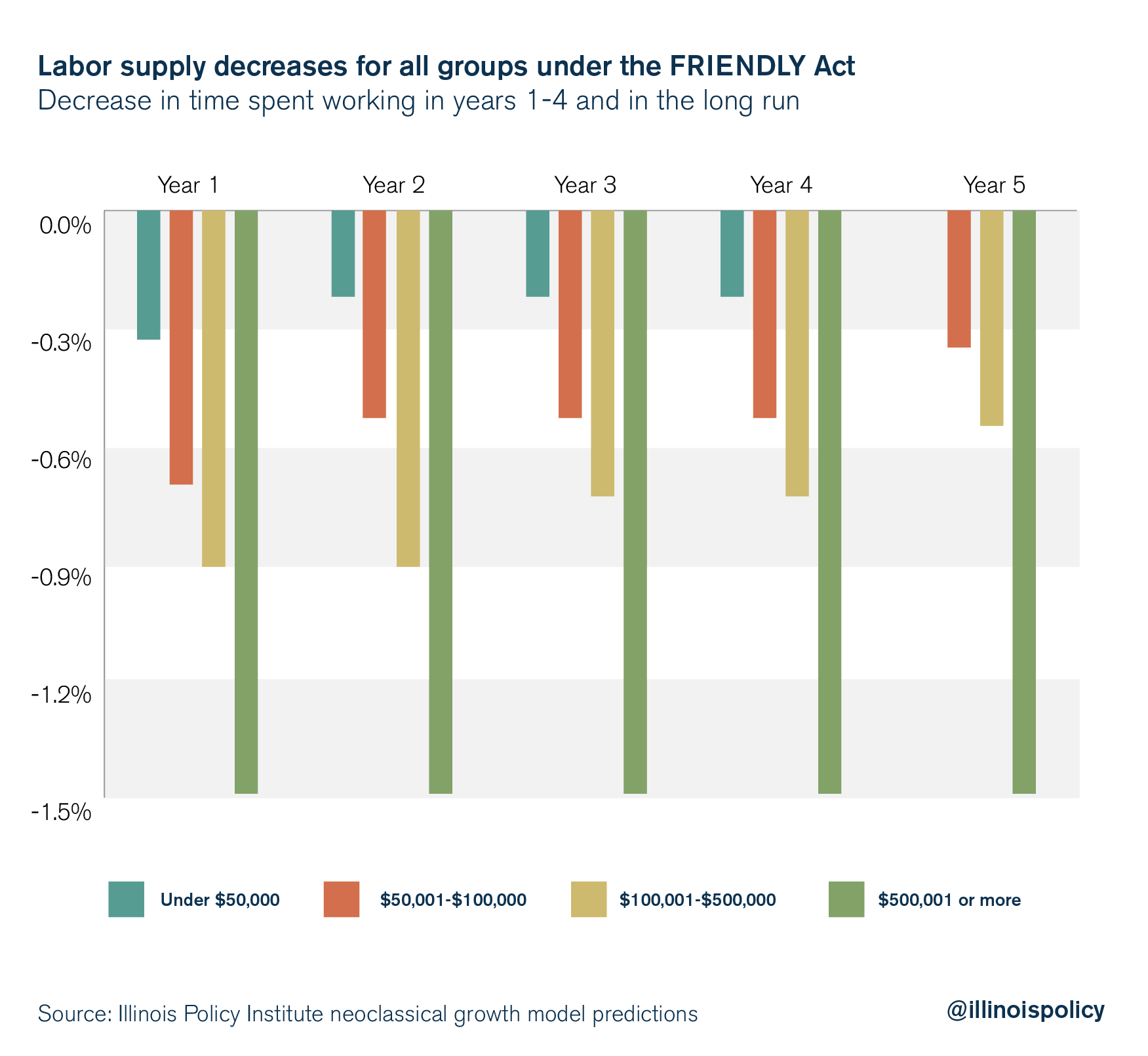

Declining real wages make workers worse off and reduce the incentive for market work relative to leisure or time spent in home production. On the other hand, a lower after-tax income raises the need to work longer hours in order to keep the value of take-home pay constant. The first effect lowers economic activity – economists refer to it as the substitution effect – while the second effect normally can offset any decline in labor supply through the so-called income effect. The impact of the tax hike depends on which one of these effects dominates the other in magnitude. Permanent (or very persistent) shocks have large income effects; hence labor works to offset the wage shock in the transmission to earnings.

The decline in the after-tax real wage results in Illinoisans choosing to work less because of the increased burden of taxation. The largest decline comes from those who are taxed at the highest rates.

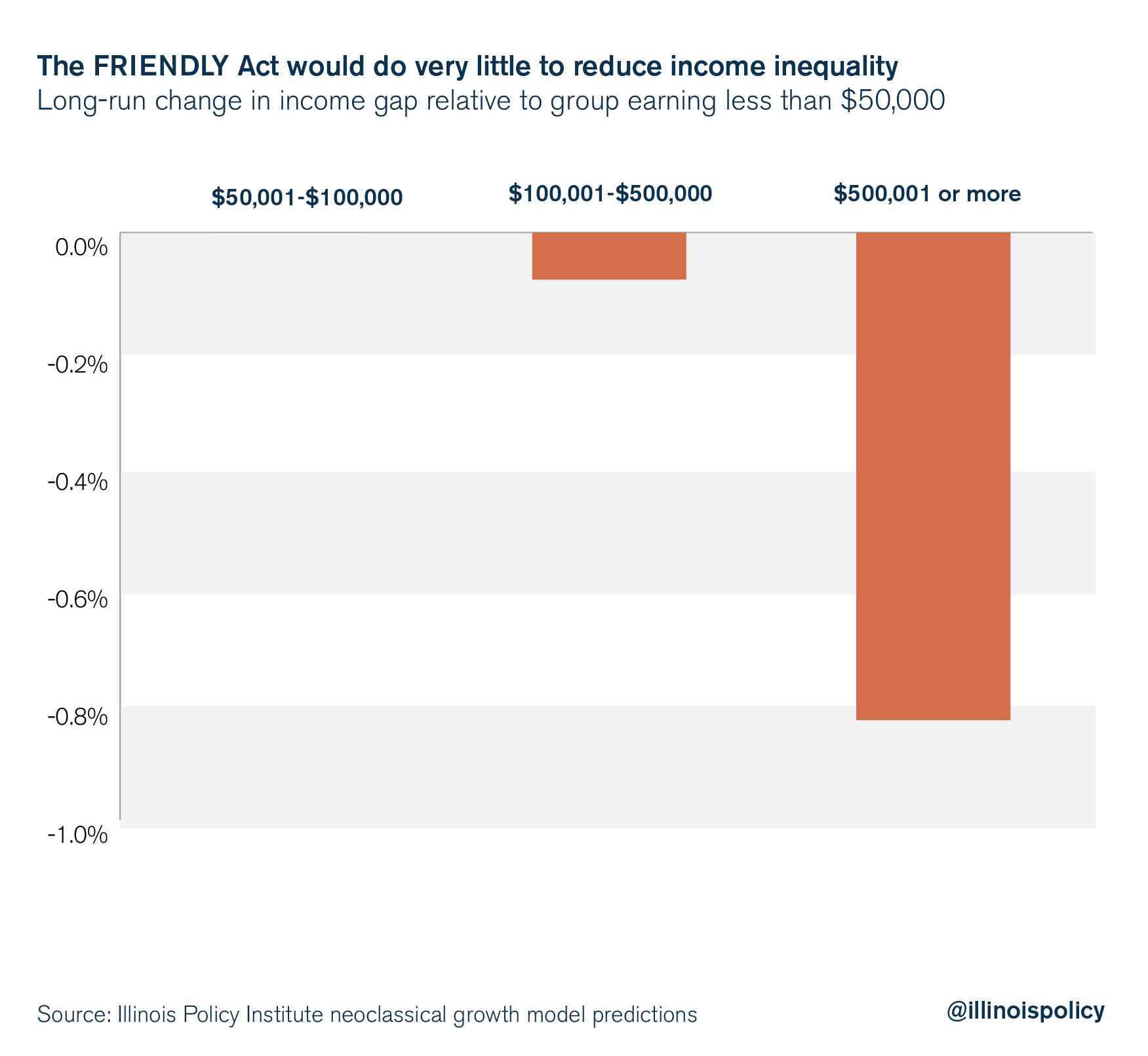

The FRIENDLY Act would reduce economic activity by nearly a full percentage point in Illinois, costing the state tens of thousands of jobs and billions of dollars in economic activity. In exchange for this economic harm, the proposal would reduce the income gap between those making less than $50,000 and those making more than $500,000 by 0.8 percent in the long run. The income gap between those making less than $50,000 and those making $100,000 to $500,000 would be reduced by less than 0.1 percent. Making all income groups worse off in exchange for these small reductions in the income gap is a foolish trade.

The effects of a shift to a progressive income tax on income inequality and individual welfare strongly depend on the specific assumptions made about individual preferences, labor supply and the income tax schedule. However, regardless of these assumptions (within reason), the effect of a progressive tax on economic activity is clearly negative.

The results from this analysis show transitioning from a flat tax system to a progressive income tax system results in reduced output, reduced labor supply and a slight reduction in the long-run income gap between earning groups. These results are consistent with Altig, Auerbach, Kotlikoff, Smetters, and Walliser (2001), Conesa and Krueger (2006), Peterman (2012), Li and Sarte (2004), Echevarria (2012), Rhee (2008), Carroll and Prante (2012), Gimenez and Pijoan-Mas (2006), Ventura (1999), and Erosa and Korkeshova (2007) (see Appendix A and Appendix B).

This potential economic harm is why Illinoisans should not allow a progressive income tax. Any progressive tax amendment would inevitably lead to tax hikes on the middle class, fewer job prospects and lower incomes.

Conclusion

Claims that a progressive tax in Illinois would produce a meaningful reduction in income inequality are dubious at best. Claims that it would spur economic growth fly in the face of macroeconomic data and the prevailing economic literature. And claims that it would provide middle-class tax relief are disingenuous, as demonstrated by the FRIENDLY Act.

Instead, efforts to pass a progressive income tax in Illinois are best understood as desperate revenue grabs in the face of persistent government overspending.

Illinois spending has consistently grown faster than residents can afford, with state spending growing 25 percent faster than Illinoisans’ personal incomes from 2005 to 2015.5 Over the same time, state debt grew to $64 billion from $51 billion – not including the $250 billion the state owes in pension debt on benefits that cannot be reduced, according to the Illinois Supreme Court.6

A progressive income tax is not the solution to Illinois’ overspending. And it will likely inflict further damage on the state’s economy. Instead, lawmakers must look to rein in the growth in state spending. Their lack of discipline has forced tax hikes, unsustainable debt and enormous uncertainty in the private sector over the future of Illinois. Rather than introducing more uncertainty with a progressive income tax system, lawmakers should adopt a spending cap that ties state spending growth to growth in Illinois’ economy. Illinoisans can then rest assured they’re getting a state government they can afford.

Endnotes

- Robert Ernest Hall and Alvin Rabushka. “The at tax,” Hoover Institution Press, Stanford University, (1995).

- Christina D. Romer and David H. Romer, “The Macroeconomic Effects of Tax Changes: Estimates Based on a New Measure of Fiscal Shocks,” American Economic Review 100, no. 3 (June 2010): 763-801.

- Olivier Blanchard and Roberto Perotti, “An Empirical Characterization of the Dynamic Effects of Changes

in Government Spending and Taxes on Output,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 117, no. 4 (2002): 1329– 1368. - Andrew Mountford and Harald Uhlig, “What Are the Effects of Fiscal Policy Shocks?” Journal of Applied Econometrics 24, no. 6 (2009): 960-992.

- Orphe Divounguy, Bryce Hill and Joe Tabor, “Restraining state spending means more certainty, security for Illinois families,” Illinois Policy Institute (January 30, 2018).

- Orphe Divounguy, Bryce Hill and Joe Tabor, “Why Illinois needs a spending cap,” Illinois Policy Institute (January 27, 2018).