Illinois General Assembly passes law allowing creation of ‘super TIFs’

A law passed by the Illinois General Assembly in June allows Chicago to create new transit-based super TIFs, adding more opportunities for city-run slush funds to divert and hoard property-tax dollars.

While public attention this spring focused on the debate in the Illinois General Assembly surrounding the stopgap budget, Illinois lawmakers quietly passed an additional bill with big-money implications. On June 30, state politicians passed a bill amending the state’s tax increment financing, or TIF, statute to allow Chicago to create four transit-based TIF districts, or super TIFs (dubbed “super” because the taxing district’s lifespan is 35 years instead of the normal 23 years). Like standard TIFs, these super TIFs would divert funds from the cash-strapped city. Unlike standard TIFs, the super TIFs could take money from one neighborhood to benefit transit projects in other parts of the city.

Chicago wanted the ability to create these super TIFs because without them the city can’t secure approximately $800 million in federal funding. The four planned projects include: improvements to Chicago Union Station; the Chicago Transit Authority, or CTA, Red and Purple lines modernization plan; the CTA Red Line extension; and the CTA Blue Line – Forest Park Branch modernization plan. In total, the four projects are expected to cost nearly $6 billion.

Funds from the super TIFs could only be spent on transit developments, meaning the tracks, stations and buildings associated with the projects.

In theory, TIFs are a mechanism providing economic incentives to developers to redevelop blighted neighborhoods. TIFs freeze the existing property-tax rate for a designated area and collect all taxes above that rate for use in the TIF. Individual taxing bodies (the city of Chicago, Chicago Public Schools, or CPS, the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District, etc.) get their usual share of the money at the frozen rate. And the mayor has carte blanche when it comes to spending TIF dollars.

In order to make the creation of super TIFs more palatable, the General Assembly included language to ensure CPS gets its full share of local property taxes at their highest levels. That means there would be no property-tax freeze in the super TIFs, and CPS would receive a state-mandated share of approximately 53 percent of the property taxes in the super TIFs. After CPS takes its allotted property taxes from a super TIF, 80 percent of the remaining property-tax revenue would be deposited into the super TIF fund. Other municipal taxing bodies, such as the water reclamation district, would receive the remaining 20 percent in proportional amounts. In order to compensate for the city’s expected loss of funds under this regime (as compared with a standard TIF district), the law increases the lifespan of the super TIF to 35 years from an ordinary TIF’s 23 years.

An Illinois House Republican staff analysis of the new super TIFs speculated, “Current TIFs within the areas intended for the Transit TIFs will be allowed to expire or could be dissolved sooner by the Chicago City Council” – meaning Chicago won’t be allowed to create multiple layers of TIF slush funds within the same areas. However, the proposed Union Station super TIF currently resides in the highly lucrative Canal Street/Congress Expressway TIF. That TIF had a 2014 closing balance in excess of $66 million and isn’t scheduled to expire until 2022. The existing boundaries of the Union Station super TIF also include the Old Post Office, which has yet to receive TIF subsidies for a proposed development.

As of 2014, 15 percent of Chicago revenues came from property taxes. Many of the neighborhoods with the highest property-tax collections (e.g., Lincoln Park, Wrigleyville, the Gold Coast) are exempt from TIFs because they are not “blighted.” They would, however, be subject to super TIFs, provided a transit stop exists within their neighborhood boundaries. Since these neighborhoods have stops along the Red and Purple lines and would fall into a new super TIF, the city would see less revenue from property taxes. This would result in city politicians making up the difference in some other way. Thus, super TIFs would likely add to the already heavy tax burden Chicago imposes on residents and visitors as politicians attempt to recoup the tax revenues that would be diverted to transit projects.

Super TIF boundaries: Taking cash from some neighborhoods to benefit people in other neighborhoods

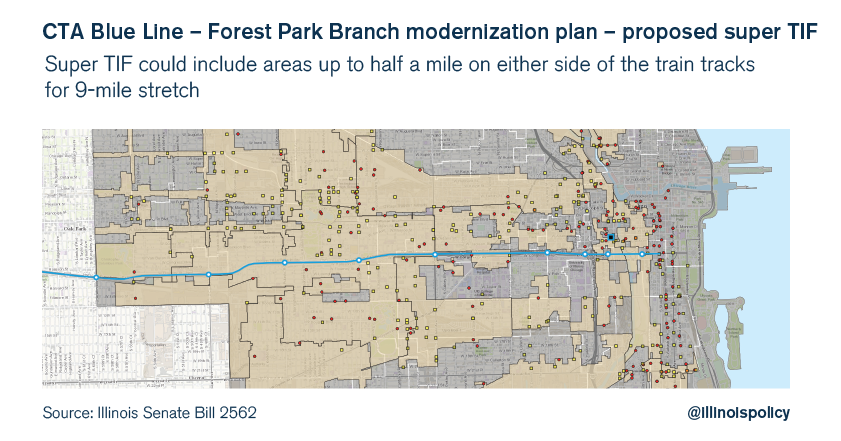

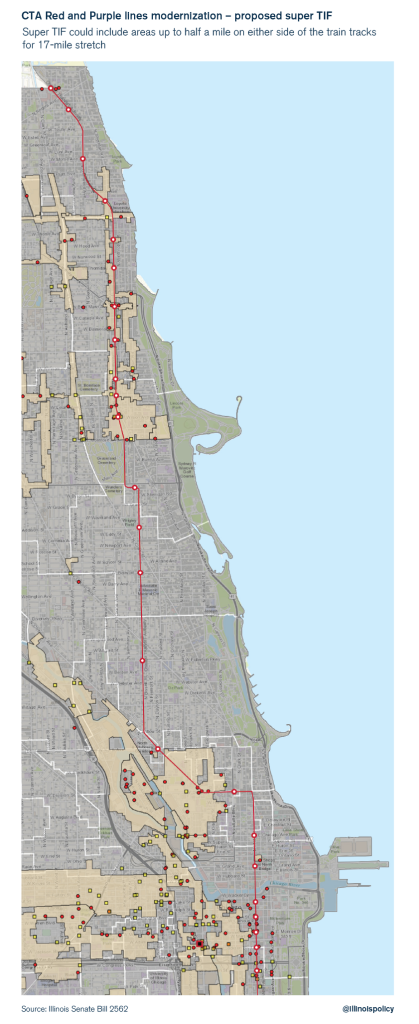

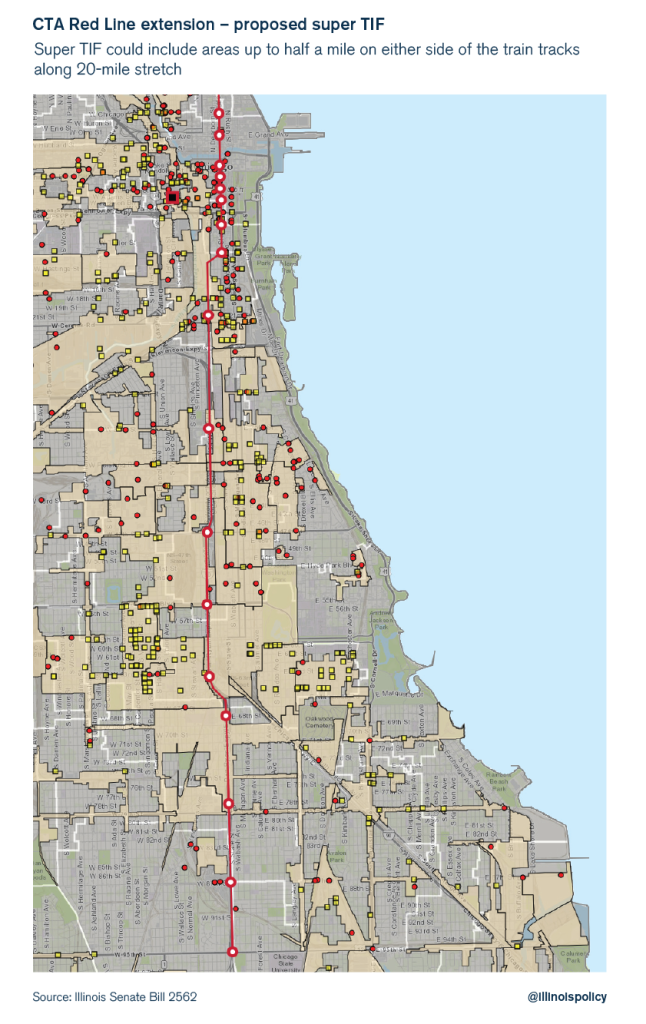

One key difference with respect to super TIFs is how the boundaries are drawn. In a standard TIF, boundaries can be arbitrarily determined to include multiple neighborhoods. In a super TIF, the district must be centered on a mass transit facility and cannot be more than half a mile in any direction.

The bill includes the train or L tracks as part of the “right of way” and allows each super TIF to continue for the following distances: 9 miles for the Blue Line modernization, 17 miles for the Red and Purple lines project, and 20 miles for the Chicago Red Line extension. But the language lacks crucial specifics regarding such matters as what constitutes a transit-related development and the exact parameters of the super TIFs.

The Blue Line super TIF would include the Loop, the medical district around Rush University Medical Center and Stroger Hospital, Lawndale, Garfield Park and Austin.

The Red and Purple lines super TIF would include River North, Lincoln Park, Wrigleyville, Uptown and Rogers Park, among other areas.

The Red Line extension would include the Loop, Chinatown, Bronzeville, Washington Park and Roseland, among other areas.

Given the diversity of the neighborhoods involved in these super TIFs, and mechanisms such as using tracks that continue for several miles as the right of way, it’s clear that this is a cash grab by the mayor to fund transit developments outside of the neighborhoods that are providing the financial support. It’s no coincidence that these are neighborhoods that do not qualify for traditional TIFs because they do not satisfy the definition of “blight.”

Given the diversity of the neighborhoods involved in these super TIFs, and mechanisms such as using tracks that continue for several miles as the right of way, it’s clear that this is a cash grab by the mayor to fund transit developments outside of the neighborhoods that are providing the financial support. It’s no coincidence that these are neighborhoods that do not qualify for traditional TIFs because they do not satisfy the definition of “blight.”

The corruption and unfairness associated with TIFs in Chicago is well-documented. TIFs have served as political slush funds into which the mayor diverts millions of tax dollars to reward his political donors. One of the chief concerns about TIFs has always been a lack of transparency. Considering the lack of specifics in the legislative text and the lack of details from City Hall, taxpayers should be extremely wary of the proposed super TIFs.

While the elimination of existing TIF districts is generally a good idea, the creation of new mechanisms to be used as a replacement slush fund is not. The prospect of these new super TIFs is giving some aldermen pause, and rightfully so. This is a deal Chicago taxpayers can’t afford to make. As the state has granted the authority to create these super TIFs, taxpayers will need to be especially vigilant and prepared to prevent City Hall from engaging in still more unaccountable taxing and spending.

Contact your alderman today and let him or her know that you oppose the creation of super TIFs.