Do Illinois homeowners get any bang for their property tax buck?

From 2005 to 2015, home values are down, property taxes are up and educational outcomes haven't seen a big improvement.

Illinoisans are forced to endure some of the highest property taxes in the nation.

However, homeowners are often told that paying such egregious property taxes is OK because, in return, they get better schools for their children and the value of their property increases. Homeowners should know that in Illinois, the jury is still out on this claim: Property taxes are up, home values are down and educational outcomes have not improved substantially.

In other words, Illinois’ high property taxes appear to have been more effective at depressing home values than improving schools.

Take a look at DuPage County, for example. Do homeowners get a bang for their property tax buck?

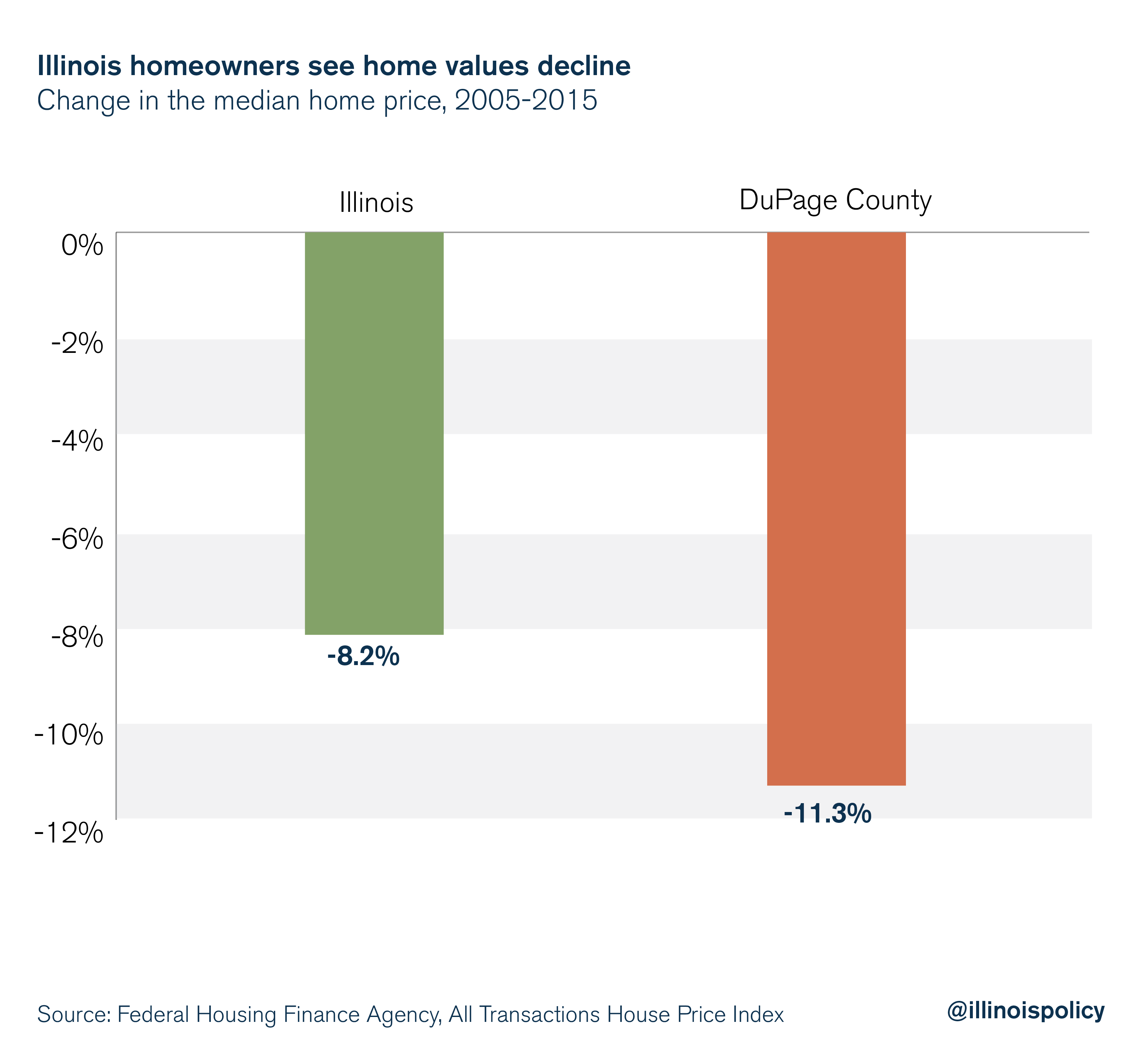

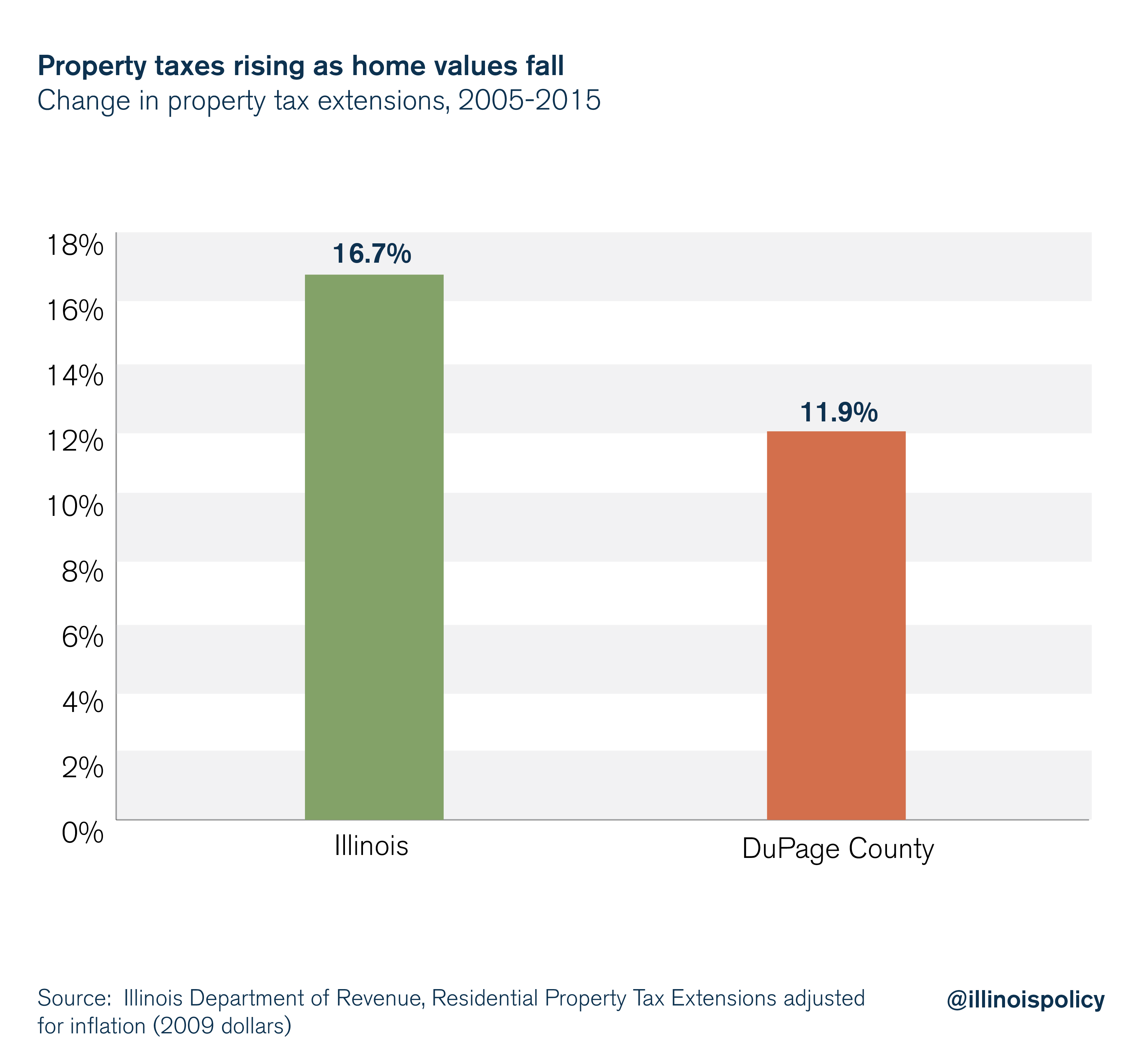

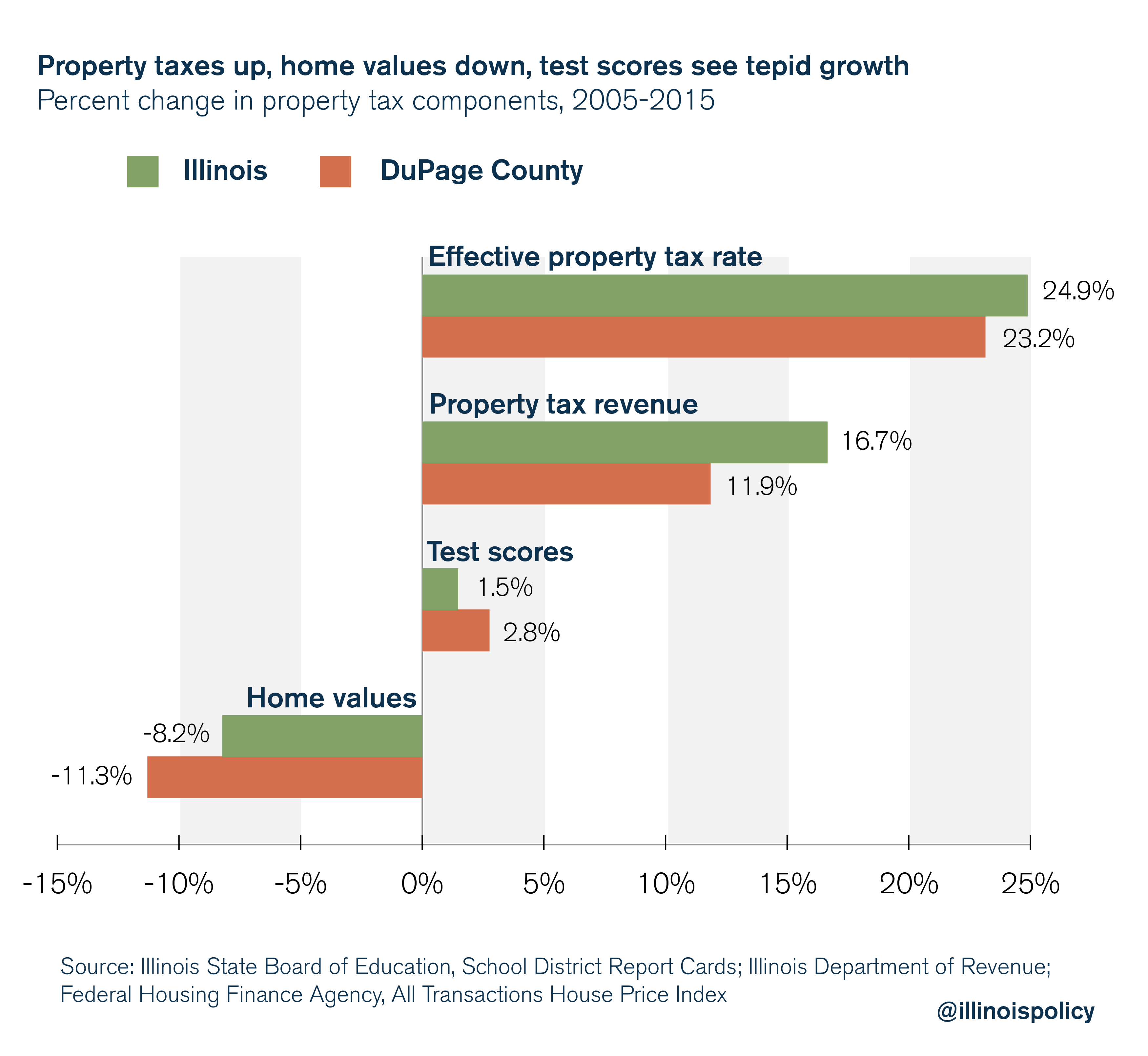

First, it’s important to note how property tax bills have grown at a time when home values have been struggling to recover. In DuPage County, property tax bills increased by 11.9 percent,1 while home values decreased by 11.3 percent from 2005 to 2015.

Although families in DuPage County – and the rest of the state – were seeing the values of their largest investment rapidly decrease, local officials refused to provide them with any reprieve from their property tax burden. In order to generate more revenue from a shrinking tax base, officials had to raise the effective property tax rate by 23 percent.

Despite a massive increase in property tax rates and school funding, DuPage residents saw a small improvement in their children’s education. The same goes for the state as a whole. ACT scores were up 1.5 percent and 2.8 percent in Illinois and DuPage County respectively from 2005-2015.

Although many factors contribute to disparities in test scores across counties or states, there doesn’t seem to be any evidence that counties that saw their property taxes and school spending increase also saw improvements in the quality of local schools. This is a big problem for homeowners, because higher property taxes without improvements in school quality lead to lower property values.

In Illinois, it simply isn’t clear that higher property taxes always lead to more success in the classroom.

The dependence of local governments on property taxes has been traditionally justified with the claim that an increase in the tax rate has little to no effect on the tax base. One explanation offered for why property taxes may not lead to changes in property values is that taxes are used to finance public services that may benefit homeowners.

When property ownership is related to individuals’ use of goods provided by local governments, such as schools or parks, then property taxes can be justified as user fees, implying that it is the provision of amenities, not property taxes that lead to changes in property values.

However, research shows that an increase in the property tax rate has a negative effect on property values, even after accounting for local public services.

Changing the system

Property taxes have skyrocketed, and most of those taxes go to local school districts.

Meanwhile, those districts’ spending priorities are often misplaced. For instance, these taxes were spent on six-figure salaries for 75 percent of superintendents in Illinois’ 852 school districts. Many of these districts could be consolidated without seeing a decline in educational outcomes.

This approach is not unproven. Nebraska reduced its number of school districts from 898 to 249 between 1987 and 2013. Nebraska is currently ranked sixth in the nation in overall K-12 education according to U.S. News and World Report. Nebraska is proof that consolidation of school districts does not come at the expense of education quality.

Local officials should begin looking outside of taxpayer wallets for real improvement in educational outcomes and efficiency. School district consolidation is one way to help not only reduce property taxes, but improve educational outcomes by removing layers of unnecessary bureaucracy in school administration.

If Illinois cuts just the number of school districts—not the number of schools—in half, taxpayers could save operating expenses of nearly $130 million to $170 million annually. These cost savings could then be passed on to taxpayers in the form of property tax relief that so many Illinois families desperately need.

1 The property tax is assessed on the value of residential real property. There is significant heterogeneity in the administration of the tax across jurisdictions. Abstracting from this heterogeneity, property tax revenue can be defined as being equal to the effective tax rate times the market value of property:

T=τV

Where τ is the effective property tax rate and V is the market value of taxable property. Holding the tax rate constant, when the market value of property increases, tax revenue increases.

Policymakers do not have to accept this mechanical increase; they may choose to offset some or all of the mechanical change by adjusting the effective tax rate. The change in tax revenue is therefore equal to the sum of the mechanical and policy offset components:

∆T=τ ∆V+∆τ V

Where τ ∆V is the mechanical change in tax revenue and ∆τ V is the change caused by a change in the effective rate – the policy change.