How to mislead Illinoisans into accepting higher taxes

A new report would have Illinoisans believe that a progressive income tax means tax cuts and economic growth. Illinois lawmakers’ tax-and-spend tendencies and evidence from all 50 states say otherwise.

A new report from the union-backed Center for Tax and Budget Accountability, or CTBA, is calling for Illinois to impose a progressive income tax. The center claims state lawmakers can have their cake and eat it too: a tax cut for a vast majority of residents, better economic growth and more revenue for the state. Those ideas have been echoed repeatedly by Democratic gubernatorial candidate J.B. Pritzker.

But these claims are too good to be true, and rely on state lawmakers who have proven all too willing to squeeze taxpayers for revenue at every opportunity. If enacted, CTBA’s recommendations would wreak further havoc on household budgets and the state economy.

The CTBA report perpetuates four major myths in its pursuit of scrapping Illinois’ flat income tax.

CTBA myth No. 1: A shift to a progressive income tax is a tax cut for Illinois families.

Fact: A progressive tax in Illinois will end up being a middle-class tax hike, as CTBA’s own projections demonstrate. Illinoisans can’t trust lawmakers to refrain from tax hikes under a progressive tax structure.

A progressive tax merely gives the state another opportunity to raise taxes on the middle class. Recall that many of the same politicians advocating for a progressive tax today promised Illinoisans the 2011 tax hike was only temporary – only to pass a permanent tax hike three years after its expiration.

Illinoisans are currently protected by the state constitution, which requires a flat tax. But the progressive tax is a gate that, once open, cannot be easily closed. Repealing the flat tax protection would require support from a three-fifths majority of the Illinois House and Senate. Once that protection is lost, taxpayers would need the same three-fifths support to reinstate it.

The CTBA’s proposed progressive tax schedule claims to raise an additional $2 billion. But that won’t come close to paying for the state’s backlog of bills, ballooning pension costs or politicians’ desire for more spending. Indeed, the CTBA’s own reporting shows the state’s “structural deficit” will return a few years after their suggested plan is enacted, meaning lawmakers will be looking to hike taxes again very shortly. And that’s only to cover the cash-based deficit, which does not take into account unpaid bills or unfunded pension liabilities.

When this occurs, the door will already be open for lawmakers to reach into the pockets of the middle class to pay for increased spending. Illinoisans need only look across the state border to see the term “rich” has been redefined to dip deep into the pockets of the middle class. A typical Illinois family would see a tax hike under nearby states’ progressive tax structures.

The rates the CTBA cites will not be etched in stone. Rebates can always be taken away, and rates can always be shifted – all to feed the insatiable spending habits of Illinois politicians. If the state can squeeze more money out of taxpayers, it will. The CTBA plan provides no spending reforms whatsoever to convince Illinoisans otherwise.

CTBA myth No. 2: Illinois’ structural deficit has persisted despite major cuts in spending over the past two decades.

Fact: Illinois does not have a revenue problem. Illinois has a spending problem.

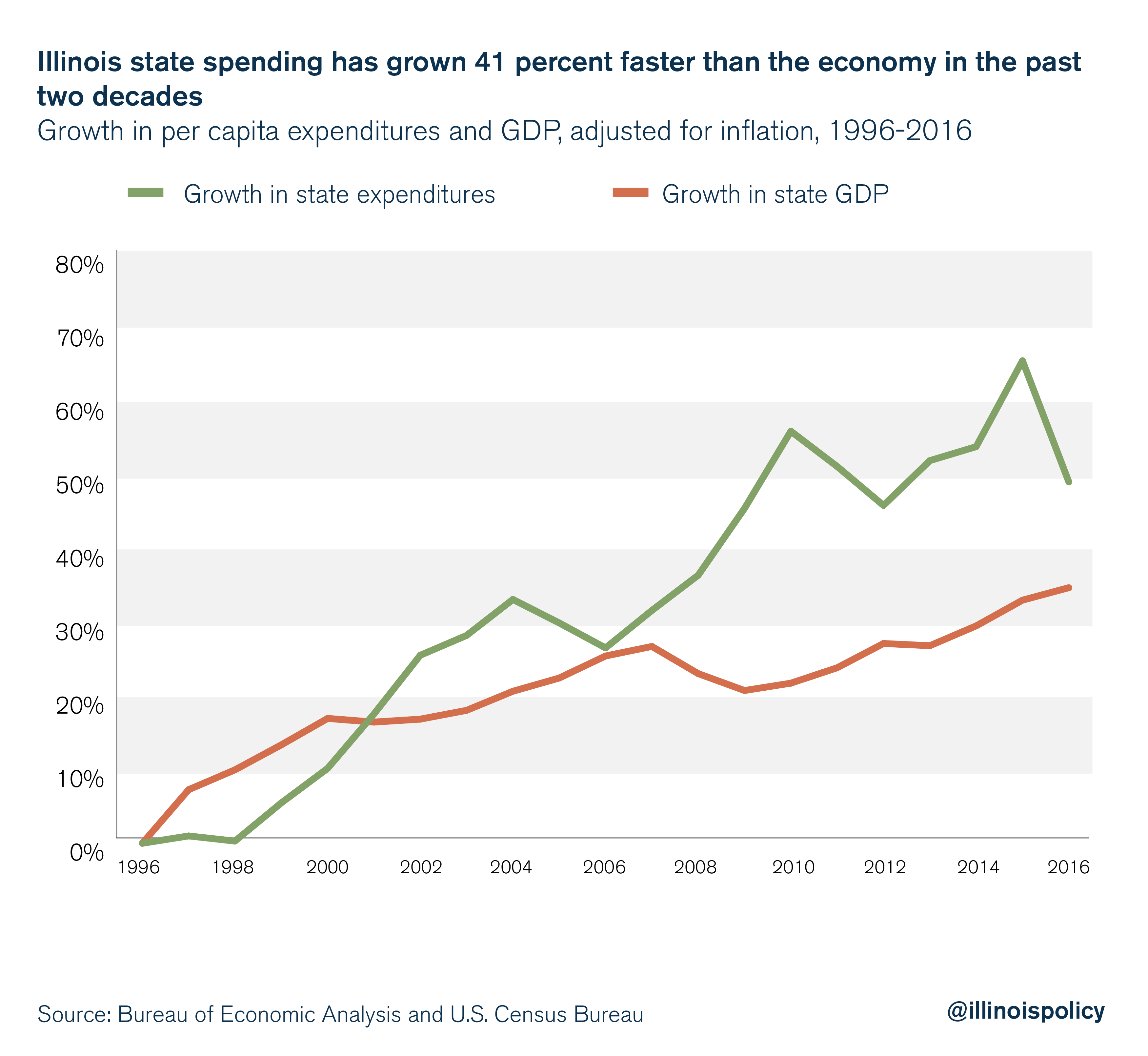

Over the past two decades, Illinois’ total state spending – state government expenditures reported by the U.S. Census Bureau – grew faster than Illinois’ economy when adjusted for inflation and population. Total expenditures grew 49 percent from 1996 to 2016, while state GDP only grew 35 percent.

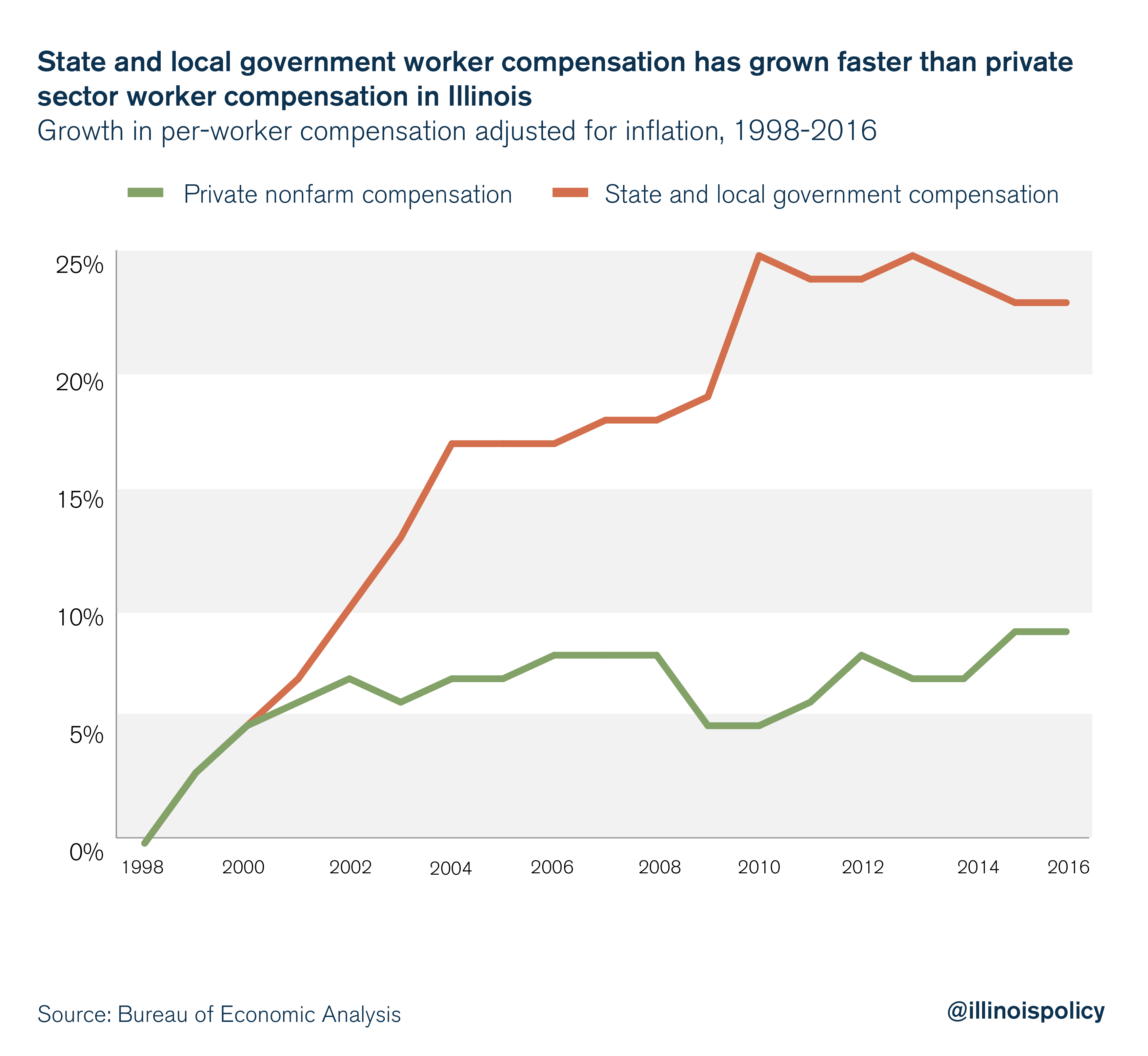

Not only that, but Illinoisans’ tax dollars have fueled public sector compensation that has grown faster than private sector compensation. Public sector compensation per worker in Illinois grew 23 percent from 1998 to 2016. Private nonfarm compensation per worker only grew 9 percent in that time.

The state should not turn to taxpayers to continue feeding this habit. Illinois should reject a progressive tax and lawmakers should learn to spend within their means – just as Illinois families do every day.

CTBA myth No. 3: The CTBA progressive tax plan will increase economic growth.

Fact: Higher tax progressivity would harm economic activity.

The CTBA report claims a reduction in state revenue has led to a reduction in government spending, and also consumer spending. The authors assert this is what hurts the state’s economy and implies Illinois must stimulate consumer spending by increasing government spending and revenue. This, CTBA claims, is one reason Illinois needs a progressive income tax.

But while an increase in consumption expenditures can stimulate the economy, an increase in investment expenditures has a much larger positive effect on economic growth. This is because investment grows the size of available capital.

The tradeoff between investment and consumption is why CTBA’s $2 billion tax hike would harm the state’s economy.

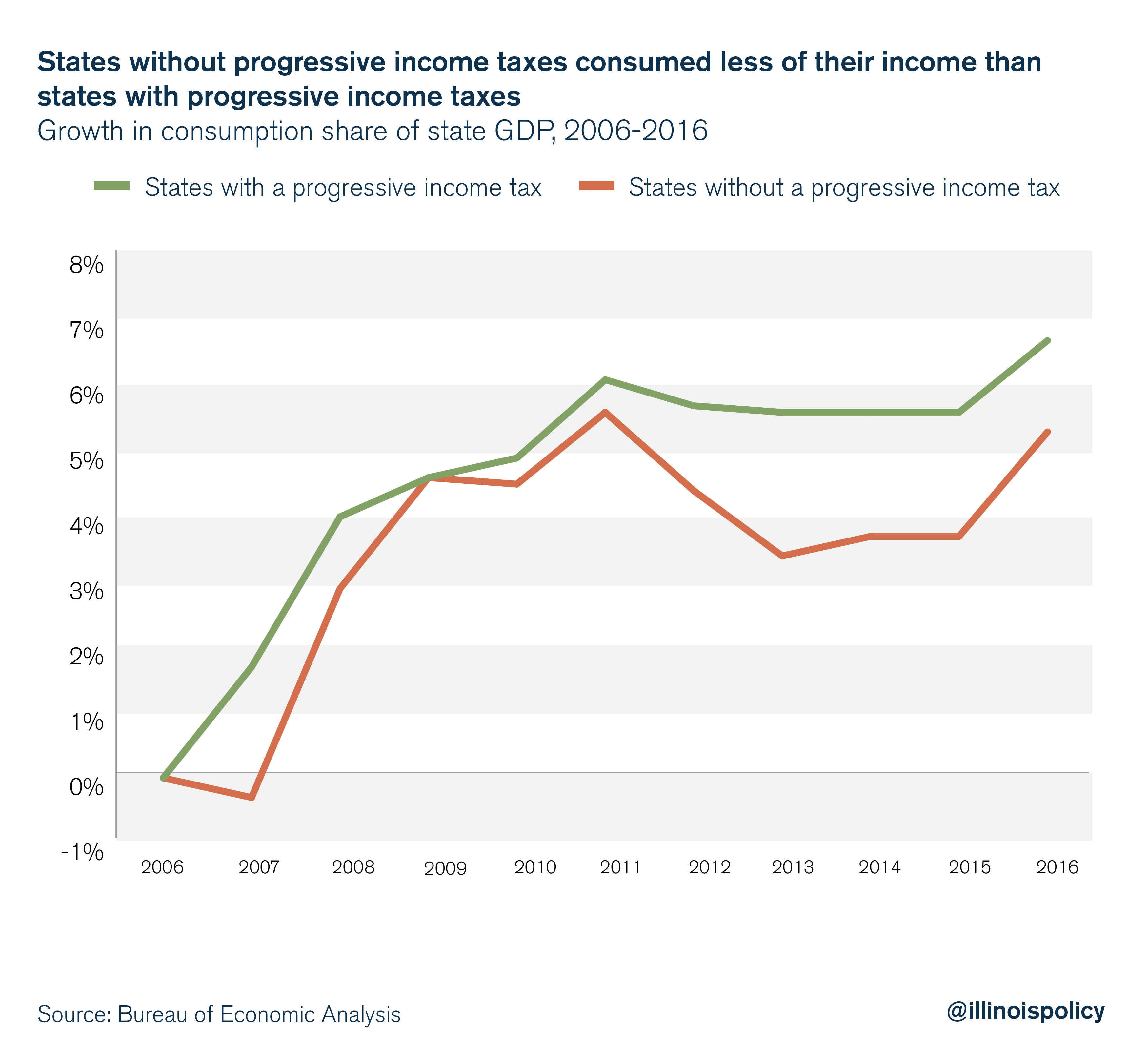

Data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis show that, in general, individuals in progressive tax states consume a larger share of their income but invest less. This leads to weaker economic growth. Consumption as a share of state GDP grew 21 percent less in states without progressive income taxes from 2006 to 2016.

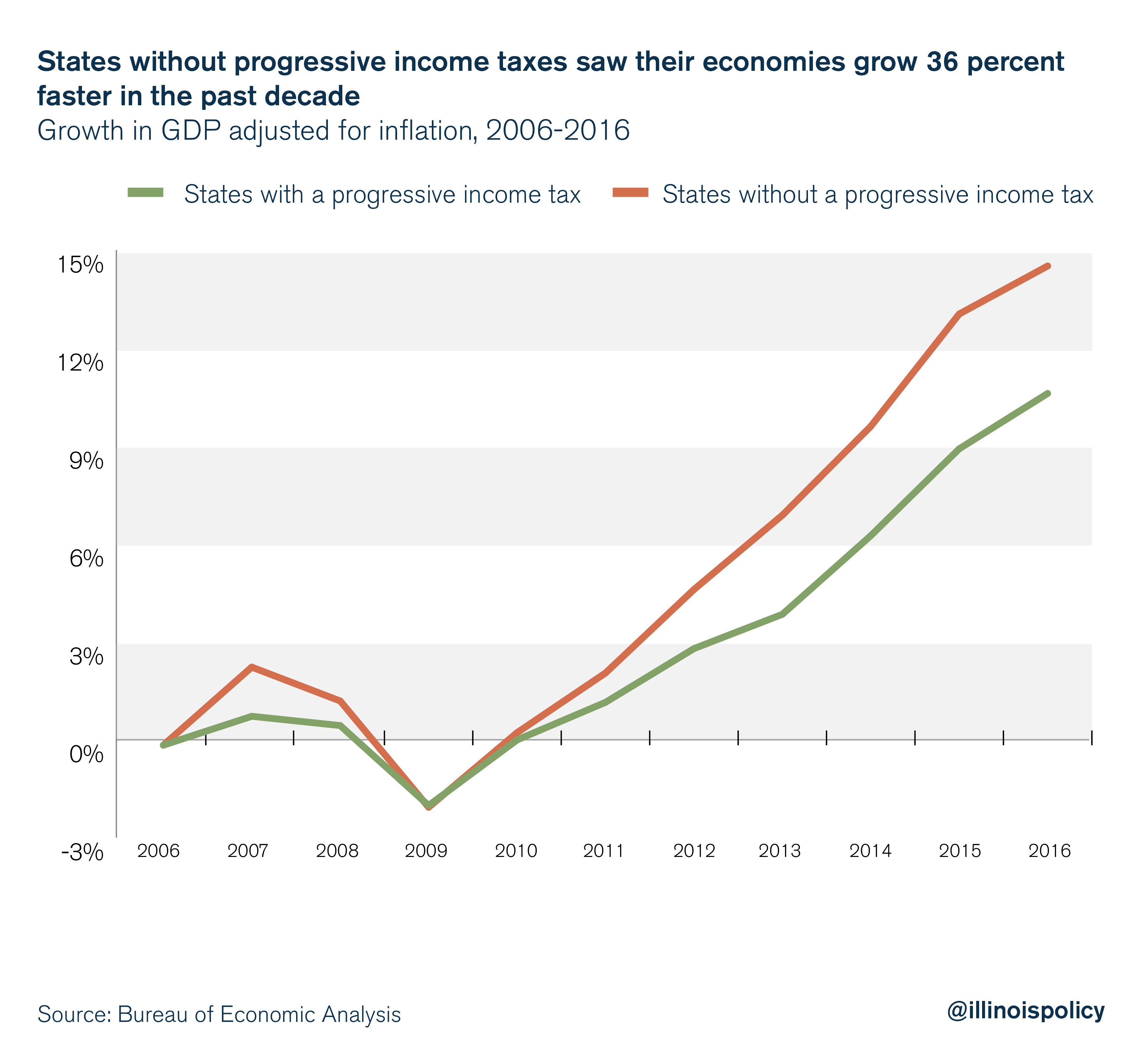

Meanwhile, states without a progressive income tax saw their economies grow 36 percent more than states with a progressive tax.

This evidence is consistent with economic theory: When investment declines, productive capital becomes scarce, output per worker – labor productivity – declines, hiring slows and so do wages for new hires. Faster productivity growth reduces unemployment by decreasing job separation and inducing job creation.

CTBA myth No. 4: Minnesota proves that a progressive income tax is good policy.

Fact: In the last decade, progressive tax states have seen weaker economic growth, weaker jobs growth, higher inequality and weaker growth in public spending and resources than states without a progressive income tax. Low-income households fare worse in states with higher income tax progressivity.

The CTBA compares the two cases of Minnesota and Kansas to argue that a progressive income tax is desirable. A more appropriate comparison takes into account outcomes in all states with and without progressive income taxes.

When comparing apples to apples, progressive tax states see weaker jobs growth, weaker economic growth and – especially interesting for progressive income tax proponents – weaker growth in government resources and spending than states without a progressive income tax. In simple terms, low-income households fare worse in states with higher income tax progressivity because it is harder to find a job, the quality of jobs is lower, there is greater income inequality and the government has fewer resources available to provide assistance.

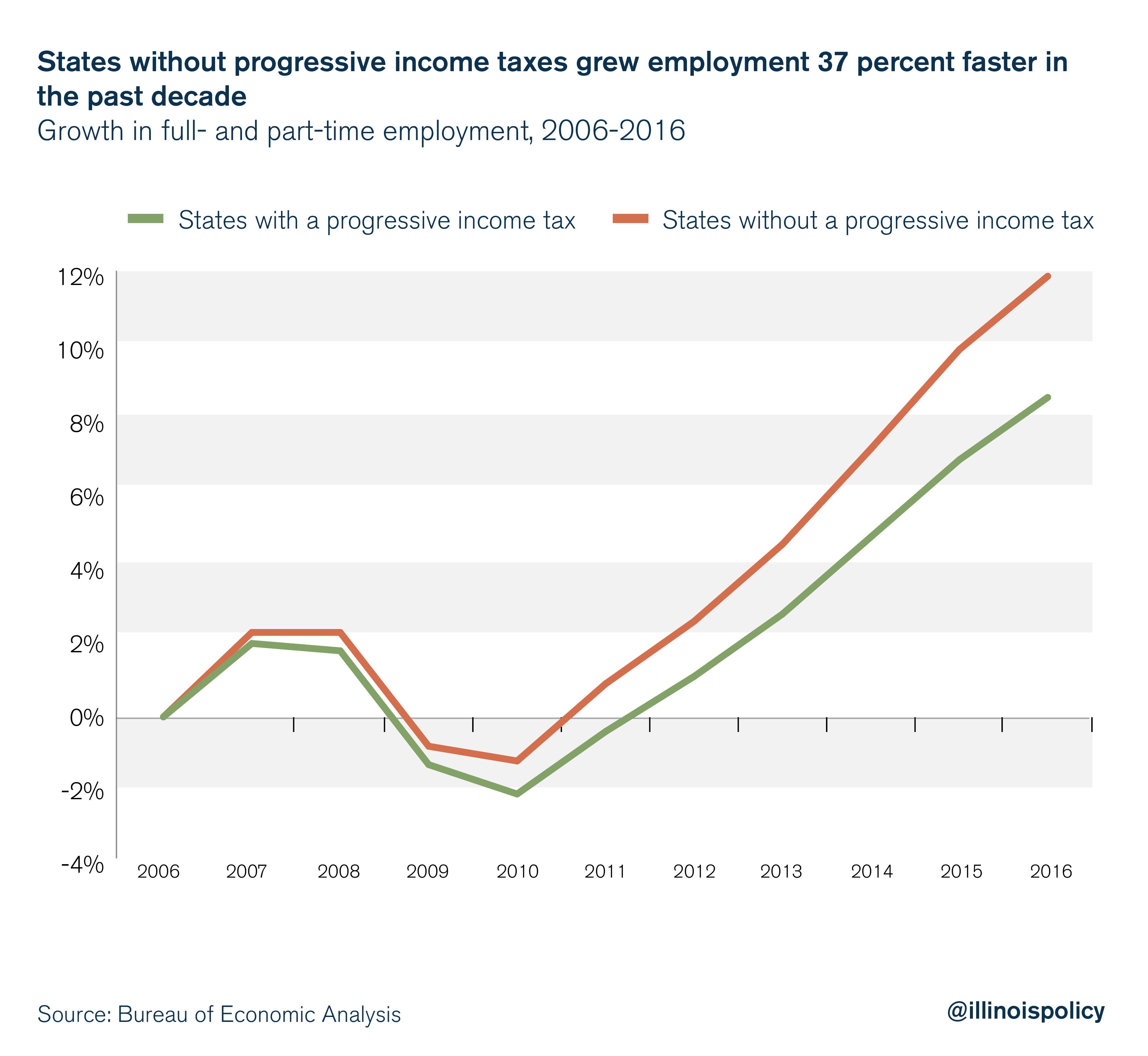

Employment

In states without a progressive income tax, employment grew 37 percent faster than in states with a progressive income tax from 2006 to 2016.

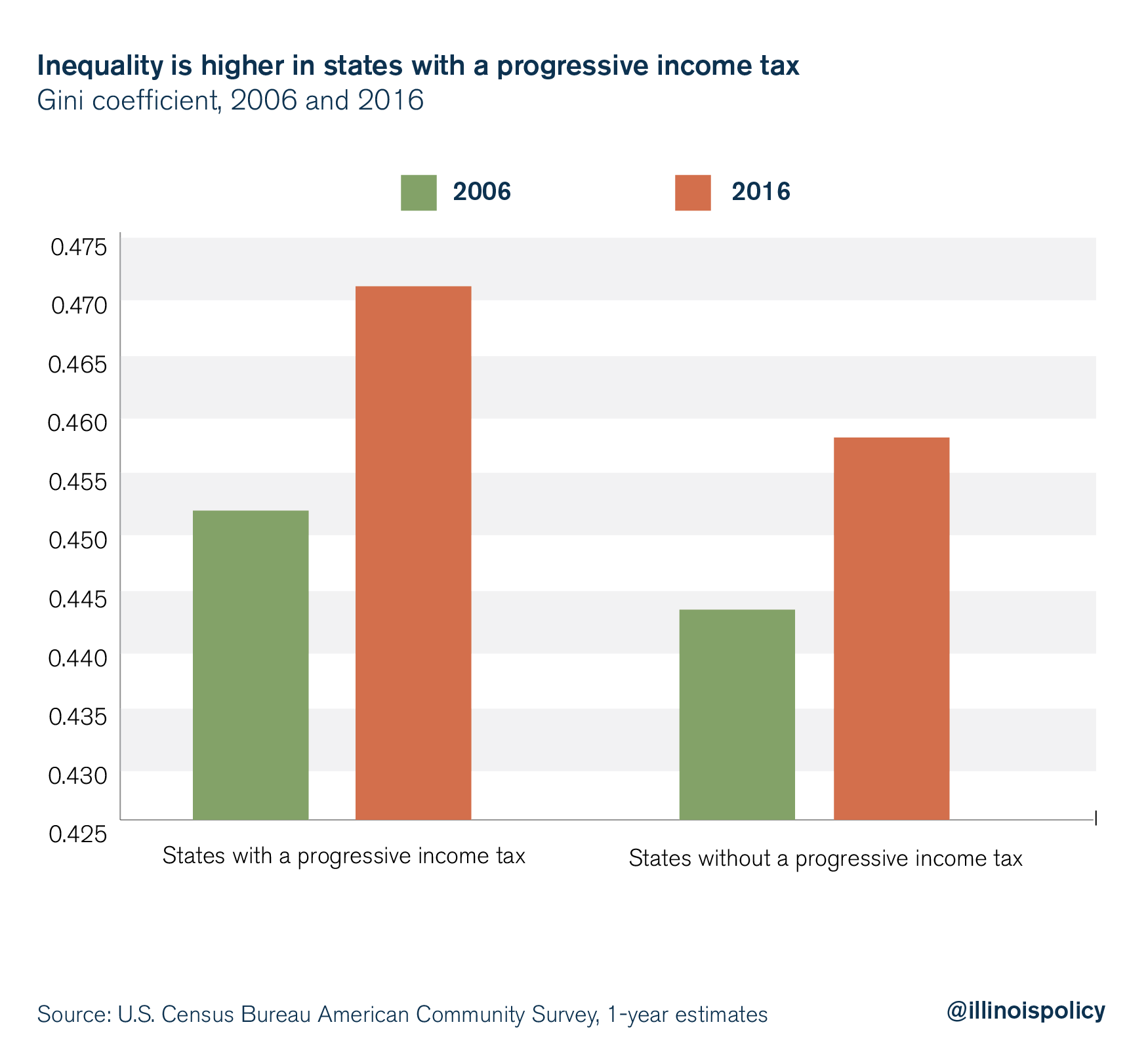

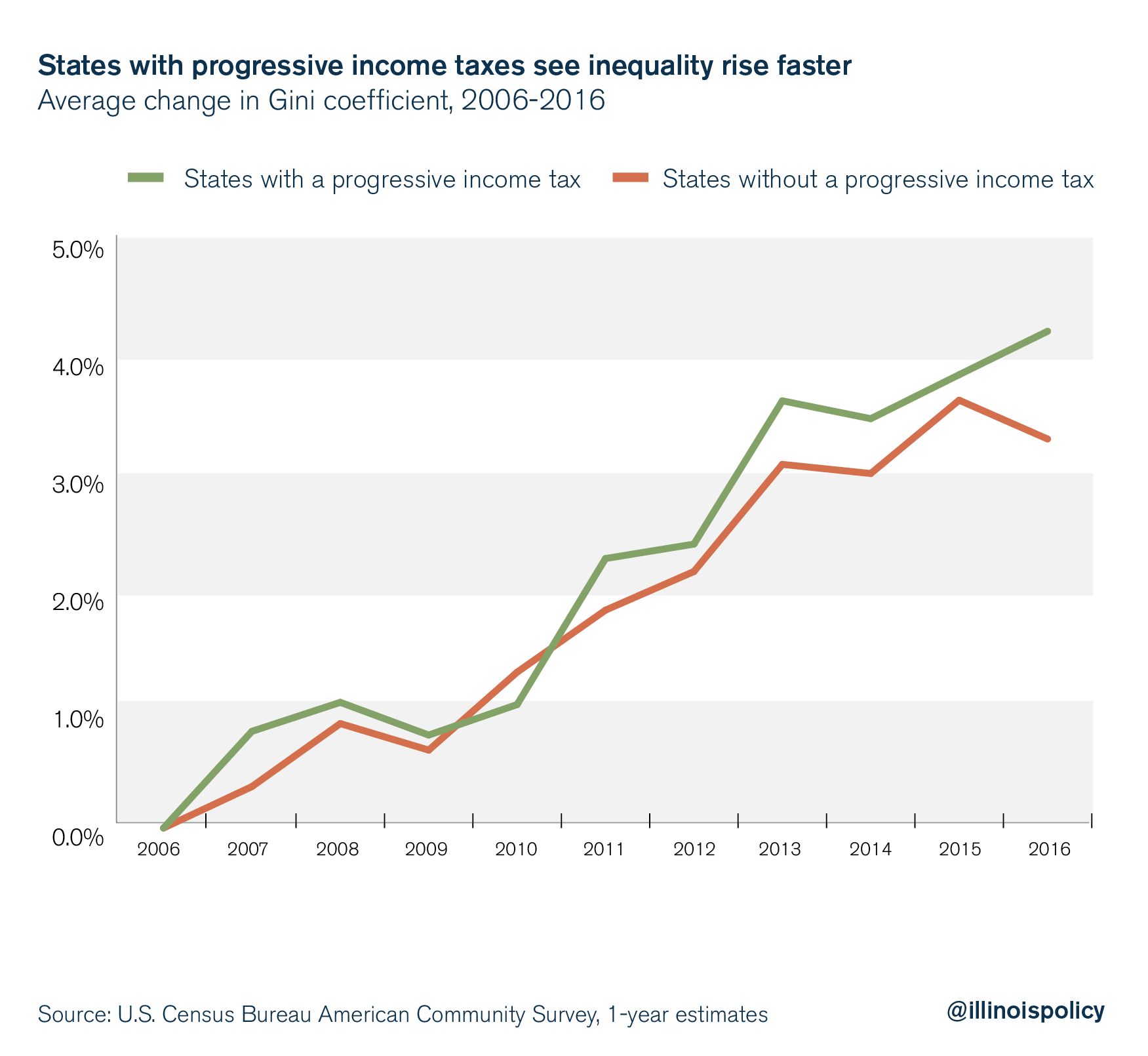

Inequality

Proponents of progressive income tax structures often claim they would go a long way in reducing income inequality. While changes in inequality reflect a host of factors, it is certainly not the case that states with a progressive income tax are more equal. In 2016, inequality in states with a progressive tax was 2.8 percent higher than states without a progressive income tax, as measured by the Gini coefficient.

Not only is inequality higher in states with a progressive income tax, but inequality has risen faster in those states as well. Inequality in states with a progressive income tax grew 4.2 percent from 2006 to 2016, while inequality grew by 3.3 percent in states without a progressive income tax.

The evidence substantiates the expert literature on this topic, which highlights that if individuals are taxed at a lower rate while unskilled and at a higher rate when they become skilled, the return to becoming skilled, skill accumulation, and growth will be negatively affected. As Nobel Prize-winning economist James Heckman (1999) notes: “For some individuals, the gain in earnings resulting from human capital investment causes them to move up tax brackets. In this case, the returns from investment are taxed at a higher rate, but the cost is expensed at a lower rate. This discourages human capital accumulation.”

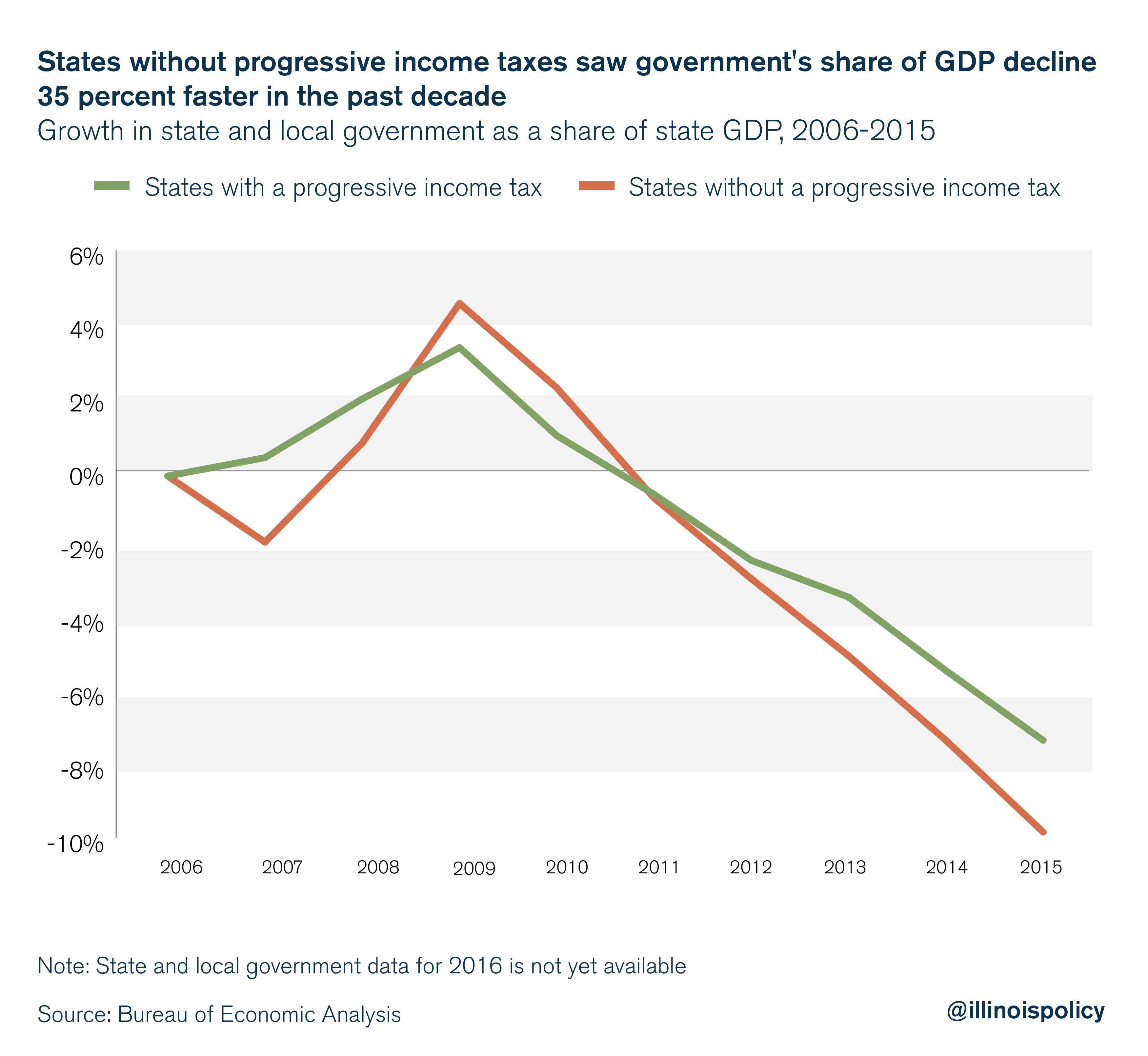

Government revenues

States without a progressive income tax have seen the government’s share of the economy decline faster than in states with a progressive tax. This might lead some to believe that progressive tax states were able to generate more revenue and provide better services to their residents.

But that’s not the case. Because states without a progressive income tax saw their economies grow so much faster than states with progressive income taxes, state and local governments actually had more resources available to serve their communities.

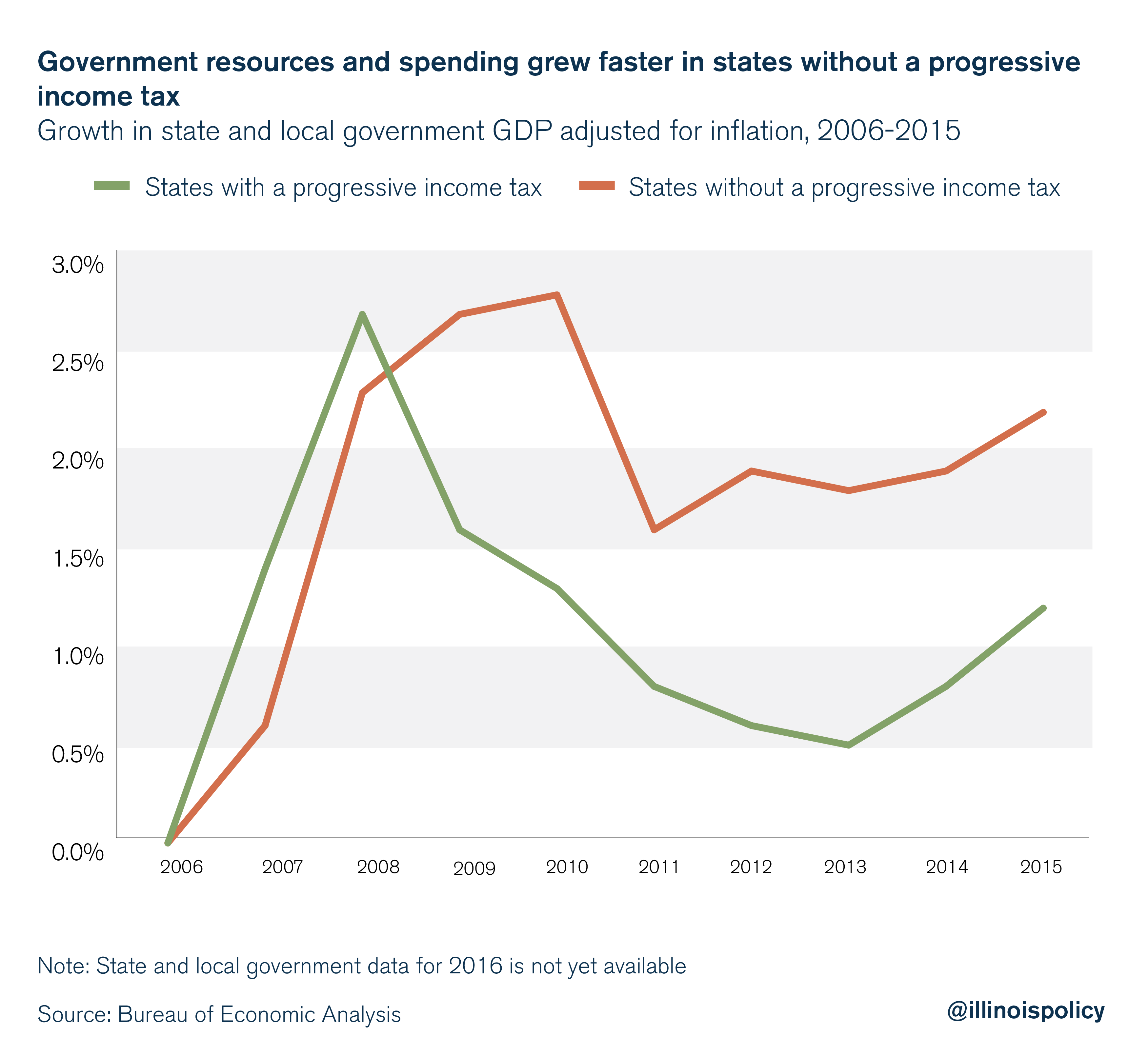

State and local government GDP – a measure of public resources and spending – grew 2.2 percent in states without a progressive income tax and only 1.2 percent in states with a progressive income tax from 2006 to 2015 (2016 data is not yet available), after adjusting for inflation.

In short, states without progressive income taxes are more competitive. And the bulk of evidence suggests that a more competitive tax code grows the tax base and improves the economy for all income groups. This is precisely why good tax policy in a global economy begins with improving competitiveness.

Conclusion

A progressive tax is a bad deal for Illinoisans. They would be giving up constitutional protections for an illusory promise from lawmakers to lower taxes. But a look at Illinois’ history and the outcomes of progressive tax states shows that promise for what it is – a lie. Any progressive tax rates will almost certainly rise to the level of spending in Springfield, and that means tax hikes on the middle class.

Illinois’ families and the state’s economy simply can’t afford more tax hikes.

Illinois is already experiencing the weakest economic expansion in state history, and a progressive income tax hike will only serve to hinder the state’s sluggish economy.

Instead, Springfield needs to learn to spend within its means. That is why lawmakers should limit growth in spending to the growth in Illinois’ economy – to what taxpayers can afford.