Introduction

No matter how bad Illinois’ finances get, one protected class of residents continues to reap higher wages and benefits: state workers.

The state has the nation’s worst credit rating. Illinois residents pay the highest median property taxes in the nation. And the state’s pension debt has reached $111 billion – with one-fourth of the state’s budget consumed by government-worker pensions.

And yet the state’s largest government-worker union is unwilling to yield on its demands for more money and better benefits. The American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees continually demands contract provisions that are devastating to the state’s finances and out of step with what the average taxpayer can afford. Taxpayers are left footing the bill for salary and compensation provisions that vastly outpace anything offered in the private sector.

Despite this, AFSCME does all it can to perpetuate the myth that it is the “little guy” – the victim – in any contract negotiations with the state. The evidence paints a different picture.

Illinois state workers are the highest-paid state workers in the nation, when adjusted for cost of living. On top of that, AFSCME workers receive platinum-level health care benefits at relatively little cost, and employees enjoy free health insurance after retirement. But employee salary and health care benefits only reveal a few of the perks AFSCME members enjoy.

The union’s contract with the state, also known as a collective bargaining agreement, or CBA, reveals additional privileges provided to AFSCME employees by the state’s overburdened taxpayers. These perks include exorbitant overtime rates and at least 15 different types of work leave, and they far outpace any benefits private-sector workers experience.

This report demonstrates the disparity between AFSCME state employees and workers in Illinois’ private sector through an examination of many of the privileges granted under AFSCME’s contract with the state.

What is AFSCME?

AFSCME Council 31 represents approximately 35,000 state government workers throughout Illinois. These government employees work in the state’s many agencies and departments, such as the Department of Human Services and the Department of Revenue, and, therefore, include various positions from interns and administrative assistants to physician specialists. Because the roles and classifications of AFSCME-represented state workers vary, union representation is actually composed of many smaller groups, referred to as “units.” During negotiations for the most recent AFSCME contract, which expired June 30, 2015, AFSCME negotiated on behalf of eight units: RC-63, RC-62, RC-42, RC-28, RC-14, RC-10, RC-9 and RC-6. (“RC” is an abbreviation for “recognized certification.”)

This use of coded categories can make it difficult for taxpayers to discern exactly whom AFSCME represents. Understanding the composition of these units can better equip taxpayers to evaluate AFSCME’s demands. When the most recent AFSCME contract expired in 2015, the median AFSCME salary was $63,660 – compared with just under $32,000 in the private sector. In fact, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, the median income for an individual AFSCME worker is higher than the median income for an entire household in the private sector (just under $58,000 in 2014).

RC-62, Statewide technical unit: This unit is composed of approximately 11,500 employees holding a range of positions, such as weatherization specialists in the Department of Commerce and Economic Opportunity, revenue tax specialists and revenue auditors at the Department of Revenue, gaming licensing analysts with the Gaming Board, and accountants and paralegal assistants in a variety of state agencies. In 2015, salaries ranged from $37,488 for entry-level revenue tax specialist trainees to $152,940 for revenue audit supervisors, with hundreds of state employees making over $85,000.

RC-42, Maintenance workers: The approximately 200 workers in this unit are employed in many state agencies across the state. Salaries in 2015 ranged from $38,800 for entry-level building/grounds laborers to $67,212 for building/grounds supervisors. The highest-earning building/grounds laborer earned $61,644 in 2015. Salaries for buildings/grounds maintenance workers ranged from $41,772 to $57,912.

RC-28, Public and client services: This group is described as a “unit composed of positions involving direct services to clients and the public.” Many of the unit’s approximately 1,700 employees are administrative assistants in the departments of Agriculture and Revenue, the Capital Development Board and Gaming Board. Salaries for the more than 570 administrative assistants ranged from $38,832 to $87,648 in 2015, but the majority (more than 430) made over $70,000. Other covered employees include dental hygienists, who earned between $51,852 and $66,960 in 2015, as well as lottery commodities distributors, who earned more than $55,000.

RC-14, Clerical workers and paraprofessionals: This unit is composed of all clerical posi- tions, as well as any “paraprofessional positions involving administrative, data treating, technical, or applied science work” in a wide range of departments, including Agriculture, Capital Development Board, Central Management Services, Children and Family Services, Revenue and Transportation. There are approximately 3,800 employees in the unit. The highest-paid positions include a conservation police sergeant in the Department of Natural Resources ($123,576 a year), a graphic arts designer in the Department of Central Management Services ($88,704 a year), and communications equipment technicians and telecommunications supervisors with the Illinois State Police ($88,704 a year). The unit includes numerous executive secretaries who earned more than $70,000 a year at the time the most recent AFSCME contract expired, including secretaries with the Illinois Lottery.

RC-10, Technical advisers and hearing referees: Workers in this unit are professional employees who listen to and make decisions related to the claims of the state’s residents. For example, it includes attorneys, or “referees,” who hear employment-related claims pending before the state’s Department of Employment Security. Other employees include attorneys, referred to as “technical advisers,” who advise on issues and conduct training for the Department of Children and Family Services. The unit is composed of approximately 300 workers and includes employees in a number of additional departments, including the Department of Revenue and the Department of Financial and Professional Regulation. The majority of the employees in this unit made over $70,000 in 2015, with more than 140 employees earning more than $100,000. Among the highest-paid individuals are hearings referees in the Department of Employment Security ($114,005 a year), technical adviser advanced program specialists within the Department of Revenue ($113,664), and public service administrators in the Department of Public Health ($113,664). The lowest-paid employees in RC-10, such as technical advisers in the Department of Children and Family Services, made more than $50,000 a year.

RC-9, Institutional employees within departments of Human Services and Veterans’ Affairs: Among the highest-paid state workers of the approximately 4,900 employees in this unit are security therapy aides and mental health technicians, who made between $69,264 and $75,792 at the time the most recent contract expired. At the low end of the pay scale are a number of mental health technician trainees, whose salaries started at $30,924 in 2015. Other employees include licensed practical nurses, whose salaries ranged between $37,488 and $59,124, as well as an “apparel/dry goods specialist” who made $59,376 as of 2015.

RC-6, Department of Corrections workers: This unit is composed of approximately 8,200 employees who work for the Department of Corrections. The highest-paid state employees in the unit include correctional sergeants, corrections clerks, corrections supply supervisors, and many of the state’s juvenile justice specialists. As of June 30, 2015, when the most recent AFSCME contract expired, each of these employees earned $80,220 a year. In addition, a large portion of RC-6 is composed of the state’s correctional officers, whose incomes ranged from $48,432 to $70,404 a year. Other employees include 28 corrections locksmiths, with all but one making over $70,000 in 2015. At the bottom of the pay scale in RC-6 are correctional officer trainees, who earned between $42,432 and $48,000 in 2015.

AFSCME perks negotiated into the collective bargaining agreement

AFSCME has secured many privileges for its employees in its contract with the state. These perks include generous compensation in addition to salary, extensive opportunities to obtain time off, and lax disciplinary procedures for late or absent employees, as well as benefits extended to AFSCME employees from agreements the state makes with other bargaining units.

Generous compensation in addition to salary

Between 2005 and 2014, AFSCME salaries rose at twice the rate of inflation and five times faster than Illinois worker earnings. This is due in large part to the complex “steps” that are used to raise worker salaries from year to year. Rather than award workers with raises based on merit, AFSCME workers are automatically granted increases in pay based on years of service and job classification.

But the AFSCME contract also provides extra ways in which AFSCME workers can earn additional pay. From overtime pay after working only 7.5 hours in a day, to double time (or more) for holidays, to overtime pay to attend weekend conferences, these benefits outpace what most taxpayers obtain in their own private-sector jobs.

1. General overtime pay

Under the AFSCME contract, overtime is computed according to the number of hours of work an employee completes in a 24-hour period. For each AFSCME unit represented in the bargaining agreement, the contract provides the following:

Full-time employees shall be paid at the rate of one and one-half times the employee’s straight time hourly rate for all time worked outside of their normal work hours and/or work days up to sixteen (16) hours in a twenty-four (24) hour period. For hours worked in excess of sixteen (16) in a twenty-four (24) hour period, employees shall be paid double time.

Rather than being paid overtime after reaching a certain number of hours in a workweek, overtime is paid as soon as the employee works any time outside of his or her “normal hours” – which for some AFSCME units is defined as just 7.5 hours in a day.

As such, the CBA’s definition of “normal time” for various units boosts the opportunity to earn overtime pay. For employees in RC-14, which includes all clerical positions, the “normal” workday is to consist of 7.5 hours, for a total of 37.5 hours in a workweek. The same is true for employees in RC-28, which includes administrative assistants, and RC-42, which includes maintenance employees. As soon as one of these covered employees works more than 7.5 hours in a day, he or she will be paid at one and a half times the hourly wage for the time worked after the 7.5 hours.

This computation of overtime differs from federal regulations. As explained by the U.S. Department of Labor, the federal Fair Labor Standards Act, which regulates overtime pay, applies on a workweek – rather than workday – basis. Further, the federal regulations define a workweek as 40 hours. As such, federal regulations dictate that overtime pay begins after an employee has worked a total of 40 hours in a workweek.

2. Holiday overtime pay

In addition to general overtime pay, employees are offered lavish holiday overtime pay.

If an employee is required to work on a holiday, he or she may receive time off from work at a later date to compensate. But in lieu of equivalent time off, an employee may choose instead to receive double-time cash payment for working on the following holidays or their observed days: New Year’s Day, Martin Luther King Jr. Day, Lincoln’s birthday, Presidents Day, Memorial Day, Independence Day, Columbus Day, Veterans Day, the Friday after Thanksgiving, and Election Day. This means that an AFSCME employee working on Election Day will earn double his or her normal rate of pay for each hour worked.

In addition, employees can be paid even more than double time for certain holidays. Labor Day, Thanksgiving Day and Christmas Day are a sort of “super holiday” – if an AFSCME employee works on one of those days, or the day on which the holiday is observed, the employee can choose to receive double-time-and-one-half cash payment in lieu of time off.

Similarly, educators who are covered under the AFSCME contract receive double-time cash payment for working on a holiday that occurs during the academic year.

Once again, this differs from what is required under the federal Fair Labor Standards Act. That law does not require overtime pay for work on holidays.

3. Overtime for training

Many employees covered under the AFSCME contract require additional training, orientation or professional development. When employees travel for such training, and it is in excess of their normal commute and outside normal work hours, they are paid overtime.

An example demonstrates the extensive benefit of this provision. If a physician employed by the Department of Human Services needs to travel a distance that is farther than his daily commute in order to attend a weekend professional development conference, and he does not normally work on a weekend day, the travel and weekend time at the conference will not only be paid, but paid at the rate of overtime pay.

4. Pay for union work

While technically not “additional” pay, it bears noting that there are provisions in the AFSCME contract that allow workers to be paid while doing union work – that is, not the work they’ve been hired to do.

For example, the contract provides time off with pay for investigation and procedures when a union member has filed a grievance against the state. The employee and a union representative are permitted time off without loss of pay, during working hours, to investigate and process grievances.

In addition, union representatives, stewards, witnesses or grievants are allowed reasonable time off with pay, during working hours, to attend grievance hearings, labor/management meetings, meetings covering modifications of supplemental agreements, and committee meetings. Employees are also allowed time off without loss of pay to attend certified stewards training.

Ample opportunities for time off – often with pay

AFSCME employees are guaranteed extensive opportunities to obtain time off, and often with pay. The state maintains, by contract, generous vacation time for AFSCME employees: 10 workdays per year through five years of continuous service; 15 workdays per year through nine years of continuous service; 17 workdays per year through 14 years of continuous service; 20 workdays through 19 years of continuous service; 22 workdays through 25 years of service; and 25 workdays after 25 years of continuous service. Vacation time can be carried over for up to 24 months after the expiration of the calendar year in which it was earned.

Yet opportunities for time off from work encompass more than vacation time, and include extensive holiday schedules, generous opportunities to obtain leaves of absence, compensatory time in lieu of overtime pay, generous sick-time policies, and time off for union work.

1. Holidays

All AFSCME employees are guaranteed 13 holidays under the collective bargaining agreement: New Year’s Day, Martin Luther King Jr. Day, Lincoln’s birthday, Presidents Day, Memorial Day, Independence Day, Labor Day, Columbus Day, Veterans Day, Thanksgiving Day, the Friday after Thanksgiving, Christmas Day and Election Day.

If one of the holidays falls on an employee’s scheduled day off, or the employee works on the holiday, equivalent time off is to be granted to the employee in the 12-month period following the holiday. Or, as noted above, the employee can choose overtime pay in lieu of compensatory time off.

By comparison, there are only 10 federal holidays; the federal list excludes Lincoln’s birthday, the day after Thanksgiving, and Election Day.

2. Leaves of absence

The AFSCME CBA includes more than 15 different types of work leave. While several of these leaves of absence are reasonable and to be expected in any professional field – such as military leave or jury duty – others go far beyond what is expected in the private sector, where it’s nearly unheard of for an employer to hold a worker’s position for an extended period of time.

What’s more, the benefits of such leaves of absence extend beyond simply the ability to take time off. With limited exceptions, an employee retains and continues to accumulate seniority and continuous service while on leave. An employee can be away from work for a significant amount of time and still earn seniority during that time. Because everything from vacation schedules to layoff priority to over-time preference is governed by seniority, this means that employees can be away from their jobs for extended periods of time and still return to a place of seniority higher than that of someone who has been working continuously. And upon return, the employee is entitled to a job in the same or similar position he or she had before, so long as someone more senior is not already in that position.

Following are some of the more generous leaves of absence.

General leave: The state may grant leaves of absence, without pay, for periods of up to six months. These leaves of absence can be extended for good cause for additional six-month periods. No standards are outlined for the granting of this leave, and it appears completely at the discretion of the state authorities supervising the employee. However, seniority and continuous service do not accumulate under this form of leave.

Leave for elected office: Any employee who is elected to a state office shall be granted a leave of absence for the duration of the elected term. There is no time limit on this particular leave of absence; it can go on as long as the employee remains in state office. However, seniority and continuous service do not accumulate under this form of leave.

Educational leave: The AFSCME contract offers two different opportunities for educational leave. First, an employee may be granted a leave of absence for one year in order to attend a recognized college, university, trade or technical school, or high school or primary school related to the employee’s employment with the state. Leave may be extended in one-year increments. Both the initial leave and any extensions “shall not be unreasonably denied.” Furthermore, employees are entitled to reimbursement of tuition expenses for academic courses, subject to the availability of funds. Seniority and continuous service continue to accumulate during this leave.

Second, if changes in certification or licensure have occurred and an employee is required to take courses on a part-time basis in order to retain the present position, the employee is to be granted reasonable time for courses without loss of pay. If the employee is required to take courses on a full-time basis, he will be granted a leave without pay. Again, seniority and continuous service continue to accumulate.

Peace Corps or Job Corps leave: Any employee who volunteers for service with the Peace Corps or Job Corps – whether overseas or in the U.S. – shall be given a leave of absence for the duration of the initial period of service. Upon return, the employee is to be restored to the same or similar position. Seniority and continuous service continue to accumulate during this leave.

Child care leave: An employee can be granted leave without pay for six months for the purpose of child care in situations where the employee’s care of the child is required to avoid unusual disturbances in the child’s life. The leave may be renewed for good cause. During this leave, seniority and continuous service continue to accumulate.

Family responsibility leave: An employee may be granted up to one year to fulfill responsibilities arising from the employee’s role in his or her family or as head of the household. A request shall not be unreasonably denied. “Family responsibility” is defined as the duty or obligation, as perceived by the employee, to provide care, full-time supervision, custody or nonprofessional treatment for a member of the immediate family or household. The CBA provides examples, called “standards,” when family responsibility leave is appropriate, including to provide nursing and/or custodial care for the employee’s newborn, to care for a temporarily disabled resident of the household, and to furnish special guidance, care or supervision of a resident of the household or member of the family. While no extensions of the leave are available, the state continues to pay its portion of the employee’s health and dental insurance for up to six months. Upon request, the employee may be granted a part-time schedule if it would not interfere with the operating needs of the state agency involved. As is the case with most of the leaves of absence allowed in the AFSCME contract, seniority and continuous service will continue to accumulate.

Leave for union office: As many as 30 employees at a time may be granted leaves of absence – for up to two years each – to serve as AFSCME representatives or officers at the international, state or local level. An employee seeking such leave can request the time off as little as five workdays before the effective date of the leave. Requests will be granted as long as leave will not substantially interfere with the state’s operations. The number and length of leaves can be increased or decreased by mutual agreement between the employee and the state. While these employees are on leave to conduct union business, seniority and continuous service continue to accumulate.

Leave for personal business: AFSCME employees are granted three personal days off each calendar year, with pay. Personal leave does not accumulate from year to year. While many private employers provide personal days for employees, it is important to note that in the case of AFSCME, these days are in addition to the extensive vacation, sick leave and other time off available to employees – and combined, it means that AFSCME’s members have extensive opportunities to take days off during the year.

Illness or injury leave (nonservice-connected): Employees who have used all of their sick days, but are unable to come back to work because of the start or continuance of a sickness or injury, may receive a nonservice disability leave. Seniority and continuous service will continue to accumulate for up to three years under this section of the contract.

3. Sick leave

Sick leave is technically one of the “leaves of absence” listed in Article XXIII, but the additional benefits that accompany sick leave warrant discussing it separately.

First, each employee receives one day of paid sick leave for every month of service – for a total of 12 sick days in a calendar year. Furthermore, sick leave is cumulative. Employees can carry over unused sick leave from year to year, with no restrictions or limitations. For example, if a 10-year employee uses only half of his sick days per year, he will have banked 60 paid sick days. A 20-year employee would have the opportunity to utilize 240 paid sick days in his career, and he could bank any unused time.

In addition, the parties have a memorandum of understanding, which is like a supplemental agreement, entitled “Affirmative Attendance Policy.” It provides that employees who have used all of their sick time shall be granted up to five additional days of “dock time,” or unpaid days, each year. Once the dock time is exhausted, the employee is to be informed of his or her right to apply for the leave of absence appropriate for the employee’s circumstances.

Another memorandum of understanding, entitled “Sick Leave Bank,” provides employees with an additional opportunity to extend their paid sick leave by another 25 days each year through use of an employee sick-leave bank. To become a member of the sick-leave bank, an employee must have five days of accumulated sick time and have donated at least one day of sick leave to the bank. If the employee or a member of the employee’s family is temporarily disabled due to a catastrophic or severe illness or injury, the employee can use 25 days from the sick-leave bank in a 12-month period.

In total, this means that an employee could be eligible to take at least 41 sick days in a 12-month period of time: 11 paid sick days, 25 paid sick bank days, and five docked absences. This differs significantly from the amount of sick leave provided to private-sector employees. Based on data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, on average, private-sector workers receive seven days of sick leave per year for one year of service, eight days a year at five to 10 years of service, and nine sick days per year at 20 years of service. And for more than half of private-sector employees, sick leave does not accumulate from year to year.

4. Compensatory time

Employees in RC-6, RC-9, RC-14, RC-28 and RC-42 are granted further opportunities to earn time off when they work overtime. Rather than being paid in cash, these employees can request compensatory time off.

While compensatory time must be taken within the fiscal year it was earned, employees can save vacation days – and carry those over from year to year – by using compensatory time instead of vacation time. Furthermore, any unused compensatory time will be liquidated and paid in cash at the end of the fiscal year.

Between vacation days, personal days, sick leave and compensatory time, AFSCME has secured extensive opportunities for its workers to take time away from their state jobs.

5. Time off for union work

In addition to leaves of absence for union officeholders, the CBA allows time off for union activities, but without pay. Local union representatives are allowed time off for union committee meetings, union training sessions, contract negotiations and state or international conventions. Such absences will be allowed as long as they do not substantially interfere with the operating needs of the state.

No limit is placed on the amount of time a union representative can be away from work, and seniority, continuous service and creditable service continue to accumulate while the employee is gone.

Lax disciplinary procedures for late or absent employees

The privileges AFSCME has secured in its contract with the state are not limited to what an employee can obtain. These privileges also include job security for employees who repeatedly miss work for unauthorized reasons.

Article IX of the collective bargaining agreement is entitled “Discipline,” and it outlines the state’s agreement with the “tenets of progressive and corrective discipline.” Disciplinary measures are to include only the following: oral reprimand, written reprimand, suspension and discharge. But taken together with other portions of the CBA, it is clear that AFSCME has negotiated provisions that protect employees from this “corrective discipline” – even if those employees have continuous unauthorized absences or are frequently late to work.

Section 1 in Article IX provides the following:

An employee shall, whenever possible, provide advance notice of absence from work. Absence of an employee for five (5) consecutive work days without reporting to the Employer or the person designated by the Employer to receive such notification may be cause for discharge. The above provision shall not apply so long as the employee then notifies as soon as it is physically possible.

Several aspects of this provision should concern the state’s taxpayers. First, five unauthorized absences “may” be cause for discharge. Use of the word “may,” as opposed to “shall,” means that discharge is not automatic at five absences. Furthermore, from the face of the text, no disciplinary measures are taken if the employee misses four or fewer days without alerting the employer. And even if the employee misses five days, he or she will not be discharged “so long as the employee then notifies … as soon as it is physically possible.” In other words, from the face of the contract, the employee can miss five days of work, not inform anyone where he is, and then notify the employer as to his absences. Notifying the employer after the fact appears to negate the possibility of discharge.

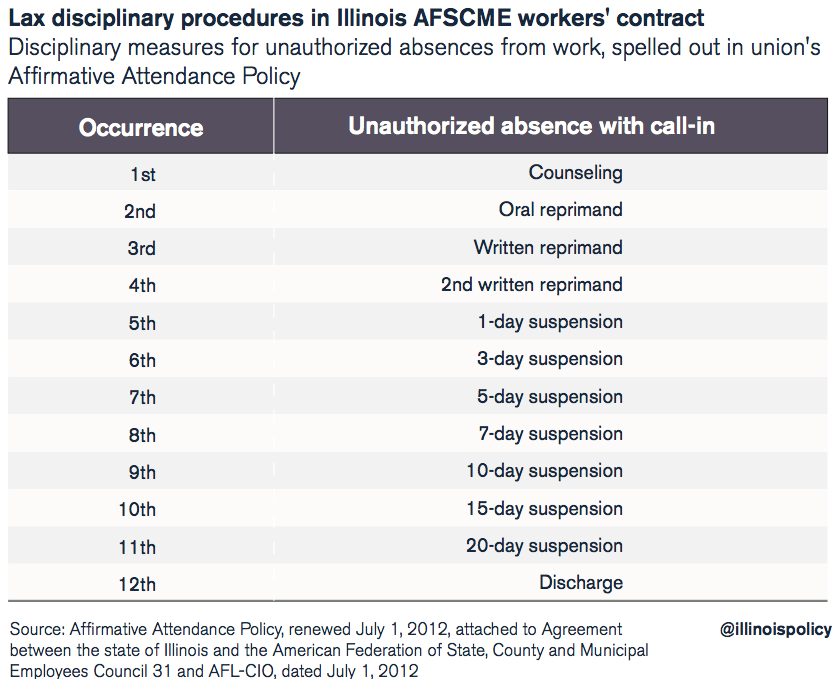

But the lax disciplinary measures for unauthorized absences do not stop with Article IX. Attached to the CBA are more than 65 “Memoranda of Understanding” – additional agreements between AFSCME and the state – including one entitled “Affirmative Attendance Policy.” In this memorandum, “corrective and progressive disciplinary action” for unauthorized absences, occurring within a 24-month period of time, is set forth as follows:

However, the memorandum also provides the following:

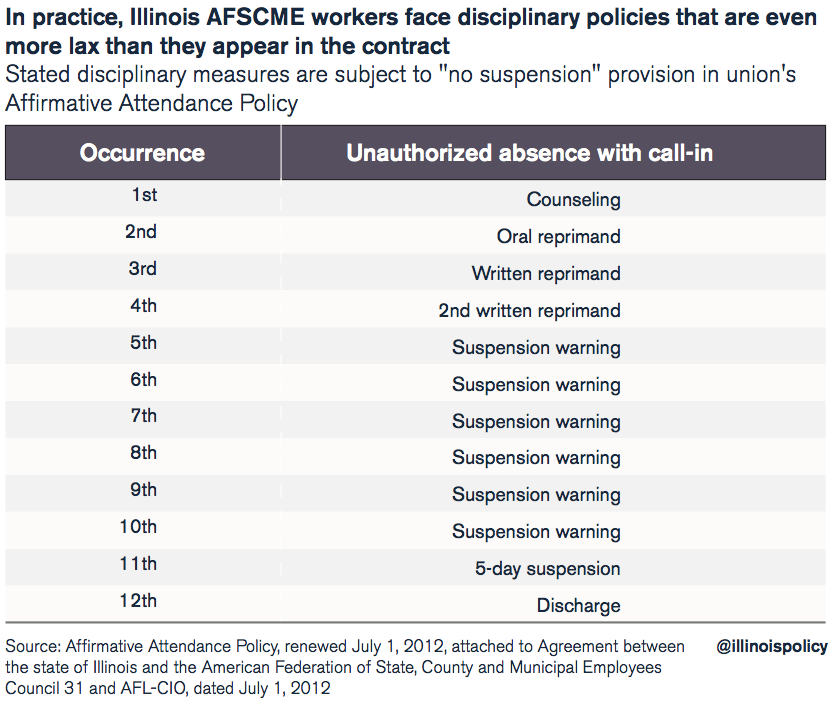

Under this Affirmative Attendance Agreement, except for the last offense before discharge, no employee will serve any suspension time. Employees will be given the usual notice of a suspension but will be expected to report to work and lose no wages. An employee will only serve five (5) days of actual suspension time for the last offense prior to discharge.

In other words, there are no repercussions for unauthorized absences until a state worker misses 11 days of work in a two-year period of time.

On the fifth, sixth, seventh, eighth, ninth and 10th absences, the employee will receive a notice of “suspension.” This amounts to nothing more than a warning, because the employee will still report to work – and get paid – during the “suspension” time. On the 11th absence, the employee will serve a five-day suspension, as opposed to a 20-day suspension. On the 12th absence, the employee will be discharged.

In practice, the policy actually looks like this:

Once two years have elapsed from the last unauthorized absence, the count starts over again.

Moreover, tardiness is not considered an unauthorized absence under the memorandum of agreement. If an absent employee is gone for less than half a day, the hours away from work will be treated as “misuse of time” and not as an unauthorized absence.

Similar to unauthorized absences, AFSCME’s contract provisions mean the state can do virtually nothing if an employee is late to work. Article XII of the CBA, which is entitled “Hours of Work and Overtime,” provides that “[t]here shall be no general policy of docking for late arrival.” An employee who is “repeatedly late” may be docked “until the problem has been corrected over a reasonable period.” However, the threshold between tardiness and unauthorized absence is one hour, meaning that an employee can be up to an hour late to work – without being docked pay – as long as it is not done “repeatedly.” And presumably, if the employee must stay late in order to finish work that was not completed within regular work hours, overtime pay will kick in as discussed above, because that time would fall outside of the employee’s “normal work hours.”

Taken together with other portions of the contract, this means that not only are the state’s taxpayers on the hook for increasing salaries and other unique privileges under the CBA, but they are also required to pay employees who may not even show up for work in a timely manner.

AFSCME is able to tap into benefits other unions negotiate with the state

The AFSCME collective bargaining agreement includes two provisions commonly referred to as “me, too” clauses: If other non-AFSCME bargaining units are given increases in pay or benefits, then the state must provide the same to AFSCME. The catch: The provisions do not apply if those other workers receive a reduction in benefits.

Specifically, Article XXXIV provides that if the director of Central Management Services grants an increase in fringe benefits to every and all non-AFSCME bargaining-unit employees who are subject to the state’s Personnel Code, then such increase shall also be made applicable to the employees covered under the AFSCME contract. But a “reduction in benefits … shall not be made applicable.”

Likewise, the contract provides that if the state voluntarily agrees to give a general wage increase greater than that given to AFSCME, or more favorable treatment for insurance premiums or health care plan design, to any other bargaining units under the jurisdiction of the governor and covered by the Illinois Pension Code or in the state’s group health and life insurance plan, the increases or favorable insurance treatment must be afforded to AFSCME employees as well.

In effect, AFSCME employees are not just granted exceptional benefits under their own contract with the state: Their benefits can also extend to include provisions in agreements made with non-AFSCME employees.