When it comes to state finances, the Land of Lincoln is a national laughing stock. Illinois has not passed a truly balanced budget since at least 2001, and is home to the worst credit rating of any state.

Taxpayers deserve to know: Why is Illinois such an outlier on budget issues?

It is easy to blame elected officials in the state, and that blame is not misplaced. Illinois lawmakers have shown a policy preference for overspending and fiscally irresponsible decision making. However, there is a less well-known culprit that is equally as important and potentially more pernicious: the budget process itself.

Expert literature shows that the budget process is an important contributor to budget substance. States with different laws and procedures around budget making have been able to enforce fiscal discipline on their lawmakers and avoid many of the issues plaguing Illinois. These issues include the worst funded public pension system in the nation, billions of dollars of unpaid bills, the nation’s lowest municipal bond rating, a tax burden that is crippling the state economy and a yearslong outmigration crisis.

The following aspects of Illinois’ budget system are particularly problematic:

- Inherently unreliable revenue estimates, which are a source of political conflict and undermine the starting point of budget negotiations

- Poor savings habits and the lack of a sufficient rainy day fund make Illinois vulnerable to fiscal shocks

- Reliance on short-term borrowing and fund sweeps for annual operating needs undermines the long-term sustainability of government spending

- Bad accounting practices for the budget process deny taxpayers transparency and lawmakers the information they need to make good decisions

These issues are interconnected and mutually reinforcing.

By demanding change in the budget process, taxpayers can put Illinois on a path to fiscal discipline – which elected officials have proven unwilling to adopt voluntarily. Lawmakers should immediately enact the following reforms to fix the four key issues with the budget process:

- Replace faulty revenue estimates with a reliable starting point:

- Adopt a spending cap – SJRCA 21 and HJRCA 38 – to improve the accuracy of budget planning and reduce political conflict in negotiations, rather than relying on imperfect revenue estimates for spending planning.

- Revenue estimates should still be required and should statutorily require automatic averaging between COGFA and GOMB estimates, rather than relying on the General Assembly to pass a resolution.

- To address a paltry rainy day fund and volatile taxes, surpluses resulting from the spending cap should be used to do the following:

- Pay down the backlog of unpaid bills.

- Rebuild the Budget Stabilization Fund to at least 5 percent of annual expenditures. Simultaneously, lawmakers should strengthen restrictions on when funds can be withdrawn.

- Cut income tax rates to provide tax relief and improve the predictability of Illinois’ tax portfolio.

- Avoid one-time revenue infusions by limiting lawmakers’ ability to rely on spending gimmicks, without creating a patchwork of constitutional carveouts:

- For example, HJRCA 16 would redefine revenue to exclude debt, refinancing and fund sweeps.

- Avoid issuing bonds to pay for yearly operations or pension costs.

- End bad accounting practices that hide the true size of deficits:

- Adopt accruals-based budgeting so that budget balance is defined by including the present value of assets and the long-term cost of liabilities.

- Strengthen the balanced budget provision of the Illinois Constitution to require end-of-year balance, rather than just prospective balance.

Illinois must adopt comprehensive solutions to fix its broken budget process.

Introduction

Illinois is recently recovering from a historic 736-day budget impasse that made national news headlines and set an embarrassing record for the longest a state has ever gone without passing a budget.1 For fiscal years 2016 and 2017, the state never enacted a full-year comprehensive budget. During this budget impasse, Illinois’ already worst-in-the-nation credit rating dropped even further.2 Recently, S&P Global Ratings blamed the state’s “persistent crisis-like budget environment” for rating Illinois bonds just one notch above junk.3 Illinois’ poor credit rating makes borrowing even more expensive for taxpayers and hurts the state’s ability to issue bonds for long term investments, such as much-needed capital improvements.4

The impasse was only ended with a record setting $5 billion tax hike that failed to solve the state’s long-running challenges. The tax hike was passed over Gov. Bruce Rauner’s veto with the help of 16 Republican votes.

Almost one year later, the General Assembly passed a fiscal year 2019 spending plan by the regular deadline for the first time since 2014. Although closer to balanced than budgets in recent years, the plan spends as much as $1.5 billion more than realistic revenue estimates, does nothing to pay down state debt5 and represents a return to status quo budget-making by relying on a number of common but deceptive gimmicks to hide its deficits.6 Credit rating agencies have already signaled they are unimpressed by the state simply enacting a budget on time when the substance of the budget still lacks meaningful reform.7

Taxpayers deserve to know: Why is Illinois such an outlier on budget issues?

It is easy to blame elected officials in the state, and that blame is not misplaced. History shows the budget is often used as a political weapon, especially in election years, rather than as the fundamental policy tool it is supposed to be.8

However, there is a less well-known culprit that is equally as important and potentially more pernicious: the budget process itself.

Illinois’ budget process is broken and does not work for taxpayers. Until the process itself is fixed, even the hypothetical best of elected officials would find fixing Illinois’ long-term fiscal imbalances a daunting task.

The Illinois Constitution requires a balanced budget: “The General Assembly by law shall make appropriations for all expenditures of public funds by the State. Appropriations for a fiscal year shall not exceed funds estimated by the General Assembly to be available during that year.”9

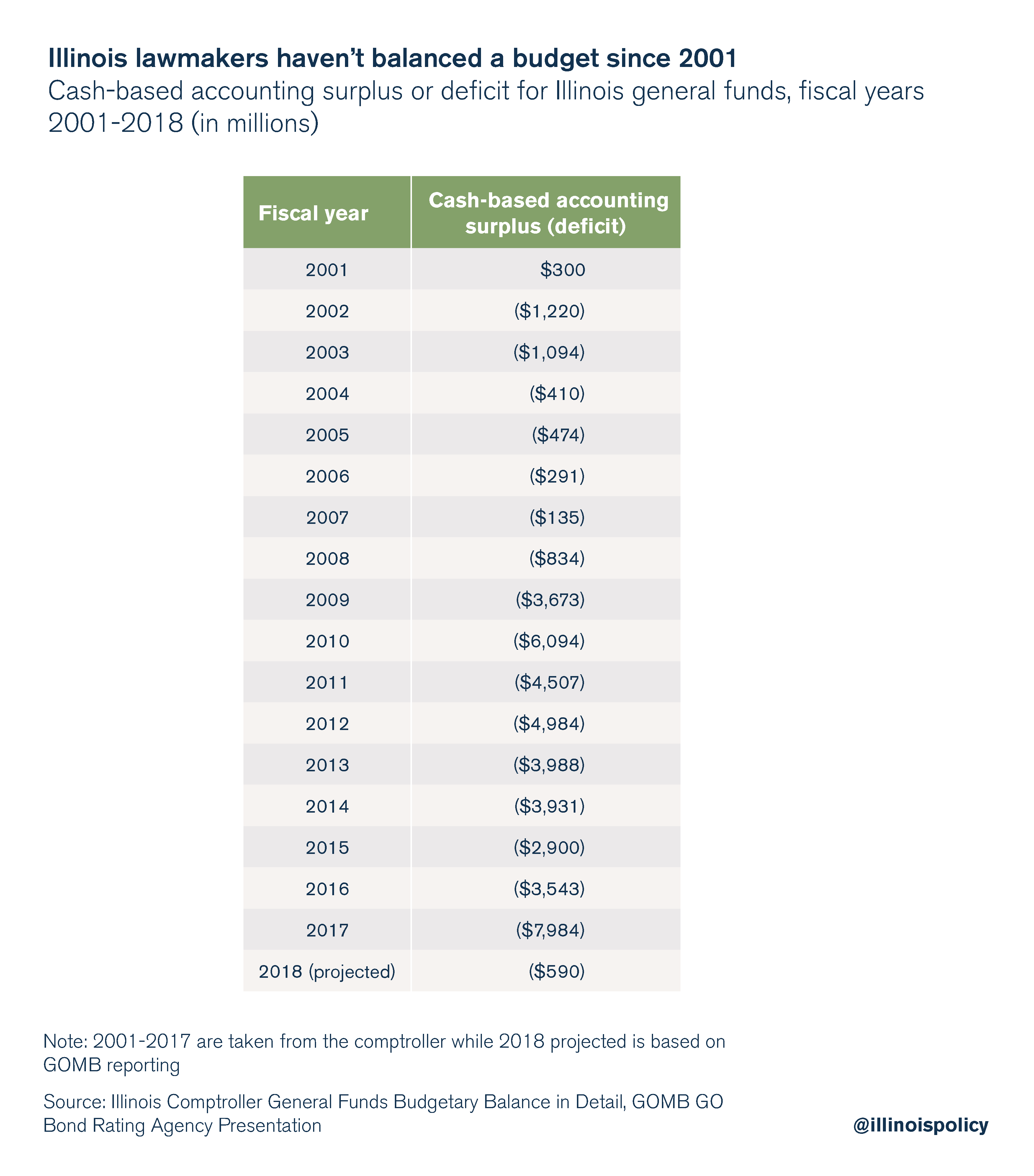

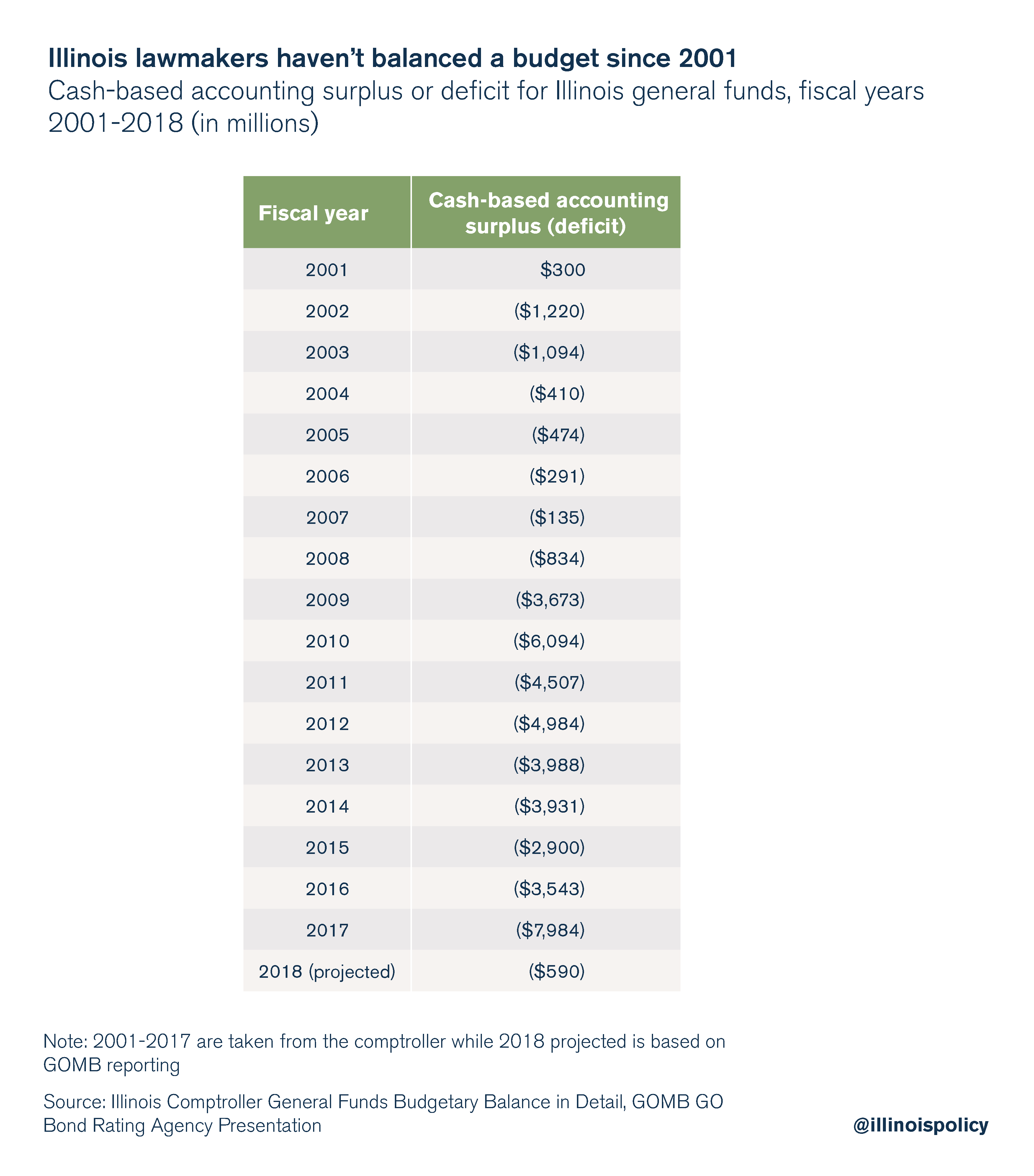

Unfortunately, this legal provision has been completely ineffective in practice. Illinois has not had a truly balanced budget since 2001.

The following aspects of Illinois’ budget system are particularly problematic:

- Inherently unreliable revenue estimates, which are a source of political conflict, undermine the starting point of budget negotiations

- Poor savings habits and the lack of a sufficient rainy day fund make Illinois vulnerable to fiscal shocks

- Reliance on short-term borrowing and fund sweeps for annual operating needs undermines the long-term sustainability of government spending

- Bad accounting practices for the budget process deny taxpayers transparency and lawmakers the information they need to make good decisions

These issues are interconnected and mutually reinforcing. Lawmakers must adopt comprehensive solutions to fix Illinois’ broken budget process. Those solutions include: adopting a spending cap, strengthening savings habits, ending reliance on short-term revenue infusions, requiring end-of-year budgetary balance and adopting generally accepted accounting principles for budget-making.

Why process matters

The results of Illinois’ broken budget process have been disastrous for taxpayers and the state economy. A lack of reliable information for budget planning (including error-prone revenue estimates and poor accounting practices) combined with a lack of meaningful spending constraints (such as an effective balanced budget requirement or a spending cap) have made tax hikes and borrowing the most common responses to fiscal pressures in Illinois.

From 2005 to 2015, state spending grew 25 percent faster than residents’ personal income.10 This makes it impossible for a constant rate of taxation to finance government spending. The only options are to cut spending, increase taxes or borrow more money. Borrowing money is ultimately a form of future taxation, because the bill eventually comes due.11

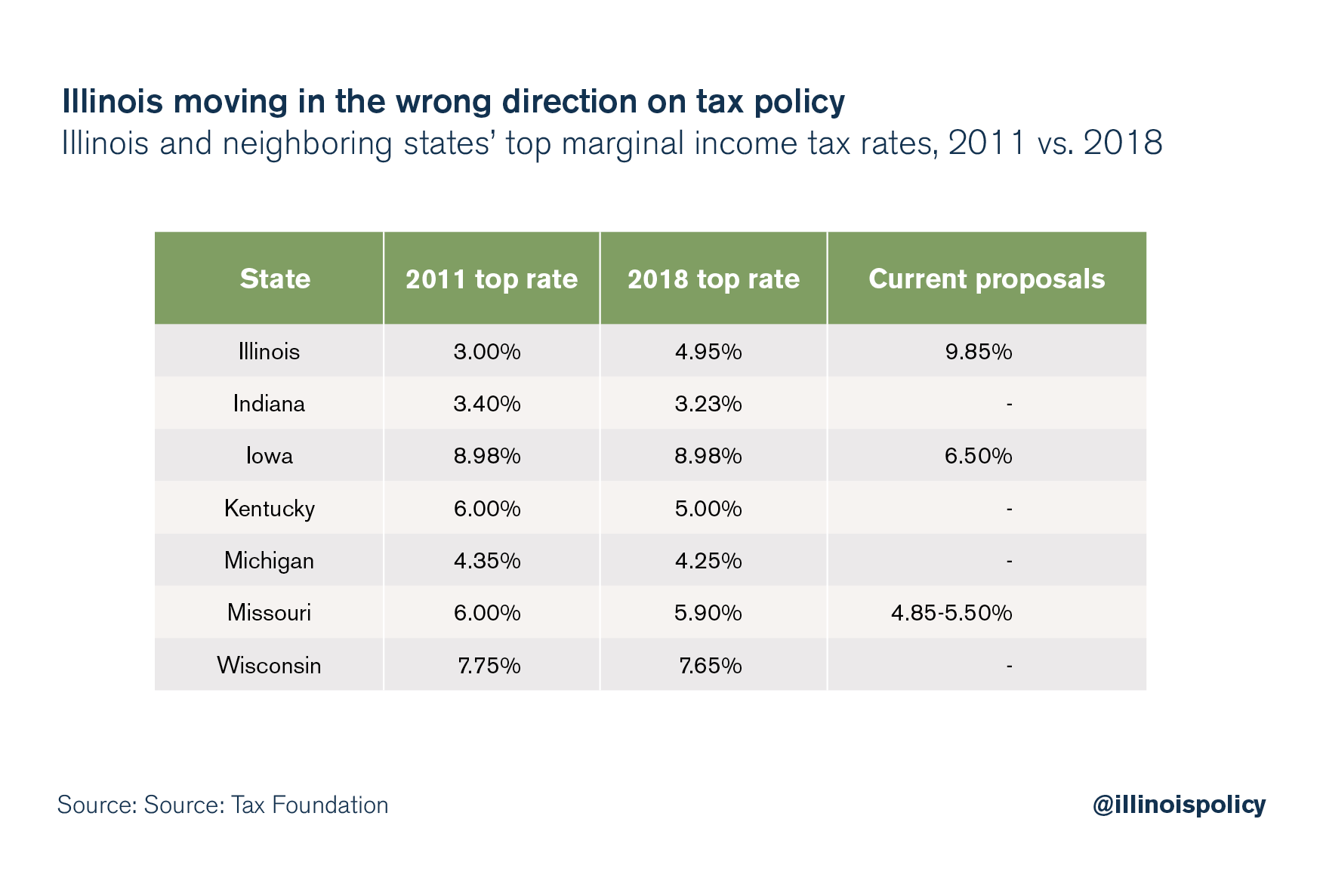

Rather than curbing spending to a level that taxpayers can afford, the Illinois General Assembly has historically opted for higher personal and corporate income taxes. A temporary income tax increase in 2011 did major harm to the Illinois economy – costing nearly $56 billion in real GSP and 9,300 jobs from 2012 to 2016 – and the $5 billion tax hike in 2017 is likely to be similarly harmful.12

This propensity for tax hikes is a major reason13 Illinois’ economy lags behind14 the rest of the United States and Illinois’ neighboring states. Illinois has also seen four consecutive years15 of population loss, a sign of a migration crisis that is hurting the labor force.16 A 2016 survey from the Paul Simon Public Policy Institute found that nearly half of Illinois residents polled wanted to leave the state, and taxes were the No. 1 reason.17

With some Illinois politicians18 and advocacy groups19 considering further tax hikes to solve Illinois’ long running fiscal challenges, every other state in the region is moving in the opposite direction regarding income taxes, toward tax relief.20

Much of the over-taxation and over-spending in Illinois can be attributed to the policy preferences of the state’s elected officials. However, evidence from around the country shows effective fiscal constraints can mitigate some of these policy choices by limiting the set of available options.21 Only when the budget process itself is sound will residents and businesses have the certainty they need to plan for the future and invest in Illinois.

The expert literature shows Illinois’ budget process is deeply flawed

In order to understand the problems with the budget process in Illinois, it is important to understand best practices from other states and what the experts say. The following is a review of the academic literature from economics, public policy and management professionals.

Best practices for revenue estimates

Process is important for estimate accuracy

The first step in planning a balanced budget is knowing how much money one has to spend. Revenue estimation or forecasting, the process of using economic models to project how much tax revenue a state will collect in the coming year, is the traditional method for creating a starting point in public budgeting.

Ideally, revenue estimates should be built on consensus and dispassionate analysis to ensure accuracy and avoid political biases. Unfortunately, this is not always the case in many states.

According to the Better Government Association, 27 states currently have some type of “consensus budget forecasting.”22 However, experts draw a distinction between types of consensus forecasting. First, there are processes that are inclusive of both the legislature and executive branch but produce only one estimate. Second, there are processes where two different numbers are produced and then averaged into an official estimate.23 There is some evidence that averaging competing estimates is more accurate than building a single number through consensus.24

One theory for why this might be the case is that the competing estimates cancel out each other’s biases. Experts writing for the International Journal of Forecasting have noted that Republicans might overestimate revenue to rebut arguments for raising taxes; conversely, Democrats might underestimate revenues to strengthen arguments in favor of tax increases.25 Academic literature on revenue estimation has reached something of a consensus that political bias does become a consideration for both executive and legislative actors.26

Research shows that even nonpartisan civil service employees feel pressure to match the political goals of their partisan elected bosses,27 that external political pressure reduces forecast accuracy,28 and that forecasts are less accurate when one party has unified political power and more accurate when partisan power is relatively more balanced.29

Some ideas that may intuitively seem to increase accuracy can actually have the opposite effect. For example, more frequent updates to revenue estimates may actually decrease accuracy by giving more opportunity for random error or temporary fluctuations to influence the end-of-year total.30 The best time to do estimates is once annually, close to the time appropriations bills are actually passed.31

Similarly, the introduction of outside experts from academia and the business community may actually reduce forecast accuracy relative to reliance on government agencies alone. Two theories explain this phenomenon: First, it could be a case of correlation but not causation if states with more difficult to predict economies are more likely to rely on outside experts; and second, outside experts may lack the contextual and qualitative knowledge of those who work full-time within the government doing forecasting.32

Economic composition and tax portfolios affect revenue volatility and therefore forecast accuracy

Aside from the forecasting process, there are two main reasons some states have more difficulty estimating revenues than others. First, states with certain economic compositions are more vulnerable to national and international economic downturns than others.33

Second, certain tax portfolios – meaning the type of taxes a state relies on for most of its revenue – are more predictable than others.

Corporate income taxes are the most unpredictable and susceptible to change, followed by personal income tax, with sales taxes being the most stable.34 One reason for this difference in predictability is what economists refer to as price “elasticity,” or the extent to which a good is subject to a change in demand as a result of a change in price.

Taxes on the least elastic goods, such as alcohol, food, and motor fuel are the most stable sources of income and therefore the easiest to predict.35

Progressive income taxes are also more volatile than flat income taxes because they rely on a smaller tax base that includes more income from investment, or capital gains, which is highly elastic.36 In fact, revenue volatility is increasing nationwide since 2000, mostly driven by more volatility in capital gains – including during recessions – and an increase in the percentage of income from investment versus wages.37 This has made state revenue forecasting even more difficult.

How to manage revenue volatility and long term fiscal sustainability

Perfectly predicting revenues is impossible.38 A recent report by the Rockefeller Institute of Government explained the following about the term “forecast error”:

“All forecasts of economic activity will be wrong to some extent, regardless of the expertise of the forecaster or the quality of the tools used. Forecasting errors are inevitable because the task is so difficult: Revenue forecasts are based in part upon economic forecasts, and economic forecasts prepared by professional forecasting firms often are subject to substantial error; tax revenue is volatile and dependent upon idiosyncratic behavior of individual taxpayers, which is notoriously difficult to predict; and tax revenue is subject to legislative and administrative changes that also are difficult to predict.”39

There are, however, steps states can take to reduce the extent of forecasting error and minimize its negative impact on the budgeting process.

First, states can maximize accuracy. One way to do this is to build a tax portfolio that relies more on broad-based consumption taxes, rather than corporate or personal income taxes, for most of its revenue.40 Nearly all efforts to make taxes more progressive will make revenue estimates more inaccurate, including exempting goods such as food and medicine from sales taxes.41 There may be other policy reasons to pursue such a tax policy, but lawmakers should be aware of the effect on revenue volatility. Additionally, states can use consensus forecasting methods that improve accuracy and reduce political biases, as discussed earlier.

Second, states can save for the future using budget stabilization funds, also known as rainy day funds. In fact, this is one of the most common recommendations from the professional literature on public budget-making in the states.42 It is generally recommended that states maintain at least 5 percent of annual revenues or expenditures in a rainy day fund to offset lost revenue during recessions,43 but some recommendations range as high as 10 percent.44

Lastly, states can impose fiscal constraints on their budgeting processes including both statutory and constitutional spending controls. Managing long-term debt is key to fiscal sustainability.45 Spending caps, which limit increases in state spending using metrics such as economic or population growth, also reduce the impact of inaccurate revenue estimates and can actually reduce macroeconomic volatility, making revenue easier to predict.46

All U.S. states except Vermont currently require balanced budgets,47 at least nominally, and Vermont has a strong tradition of balancing its budget.48 The adoption of balanced budget requirements began in the 1830s and expanded after the Civil War to help restore bond buyers’ confidence in state government credit, which was poor at the time.49 Unfortunately, all fiscal constraints are not created equal.

Borrowing money can be a good thing in some cases, when there is a return on investment, such as for infrastructure spending.50 However, to give taxpayers and bond buyers certainty that the state can meet its obligations, long-term liabilities should always be balanced with the present value of assets held by the state.51

Moreover, balanced budget requirements that are prospective – meaning balance is required only at the planning stage – are less effective than constraints that require end-of-year balance.52 End-of-year balance, meaning deficits cannot be carried over, is required by 37 states plus Puerto Rico.53 Similarly, spending caps are more effective when they are constitutional, rather than statutory, and when they require supermajority votes from the legislature to override the limit rather than a simple majority.54

Why Illinois fails the good budgeting test

According to 2017 ratings by the nonpartisan Volcker Alliance, Illinois ranks poorly on a wide range of budget process measures.55 The Volcker Alliance gave Illinois the following grades:

- D- for budget forecasting

- D for budget maneuvers, with an emphasis on short term infusions

- D- for legacy costs

- C for reserve funds

- B for transparency

What follows is a deeper dive into Illinois’ bad budgeting basics. Unfortunately, things are worse than the Volcker Alliance reported. Since the release of that report, Illinois’ rainy day fund has been depleted even further. Additionally, transparency around the Illinois budget is even worse than what the Volcker Alliance described.

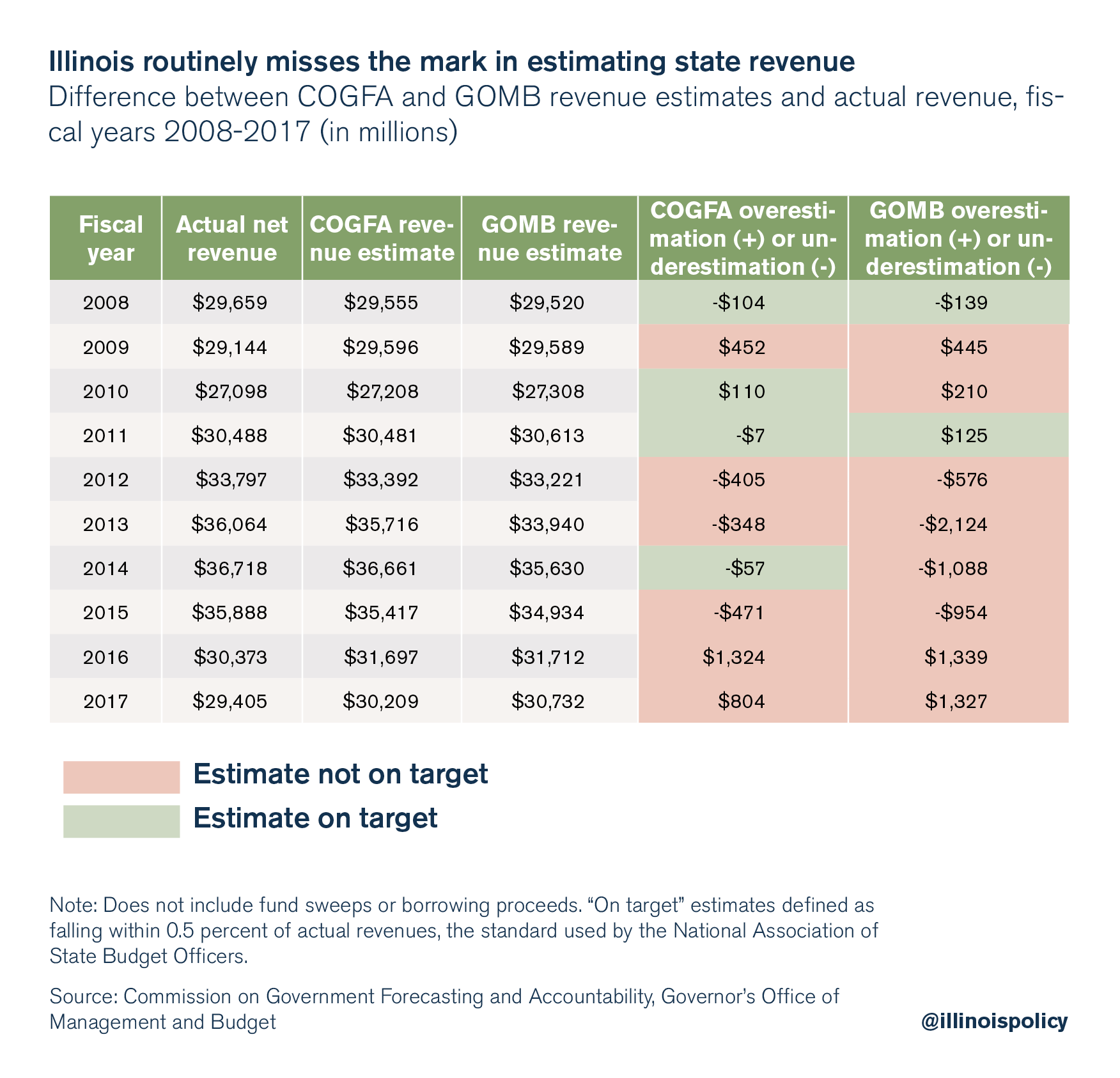

Unreliable revenue estimates add conflict and uncertainty to budget negotiations

State law currently requires two separate entities to estimate revenue for the coming year.56 The executive estimate comes from the Governor’s Office of Management and Budget, or GOMB, and is used by the governor in his annual budget proposal. A second estimate comes from the legislative Commission on Government Forecasting and Accountability, or COGFA. The General Assembly is then supposed to use these numbers to adopt its own official estimate for the budget process. There is no formal consensus forecasting process or requirement that projections from the two agencies be averaged together. Worse, these two estimates rarely match either each other or the amount of revenue that actually ends up coming in.

Based on the standard for revenue projections used by the National Association of State Budget Officers – estimates within 0.5 percent of actual revenues are considered “on target”57 – COGFA revenue estimates have been on target in only four of the last 10 years. GOMB estimates have been on target in only two of the last 10 years.

Even this standard is generous. “On target” in fiscal year 2010 meant an overestimation of $110 million by COGFA, which is the size of the annual budgets of several entire executive agencies and boards. “On target” for fiscal year 2018 would allow for an error of roughly $189 million, according to the COGFA revenue estimate.58 That’s more than the combined proposed operating budgets for the following agencies and offices:59

- Office of the Governor ($4.7 million)

- Office of the Lieutenant Governor ($1.2 million)

- Office of Executive Inspector General ($7.7 million)

- State Board of Elections ($25.4 million)

- Department of Human Rights ($15.1 million)

- Department of Insurance ($48.7 million)

- Department of Labor ($12.8 million)

- Department of Military Affairs ($64.6 million)

If revenue comes in below projections, that means adding to the backlog of bills, which GOMB predicts will stand at $7.7 billion at the end of this fiscal year.60 Ultimately, Illinois’ poor budget forecasting causes uncertainty. This uncertainty is a leading cause of Illinois’ poor credit rating.61

Worse, the General Assembly has not adopted an official revenue estimate since 2014. For the fiscal year 2019 budget, the subject of adopting a revenue estimate became a source of partisan political conflict.62

Both statutory law and the Illinois Constitution appear to require the adoption of a revenue estimate. It is impossible for the balanced budget requirement to work without one.63 Illinois Attorney General Lisa Madigan issued an informal opinion in 2014 that stated, “[T]he General Assembly’s appropriation authority is limited by its estimate of funds available, which serves as ‘a ceiling of revenues within which they must appropriate and beyond which they may not go.’”64

Adopting a revenue estimate is a necessary starting point for budget negotiations. However, by looking at patterns of the most dramatic revenue overestimations and underestimations, it appears Illinois is not free from the partisan political biases that are warned of in the academic literature.

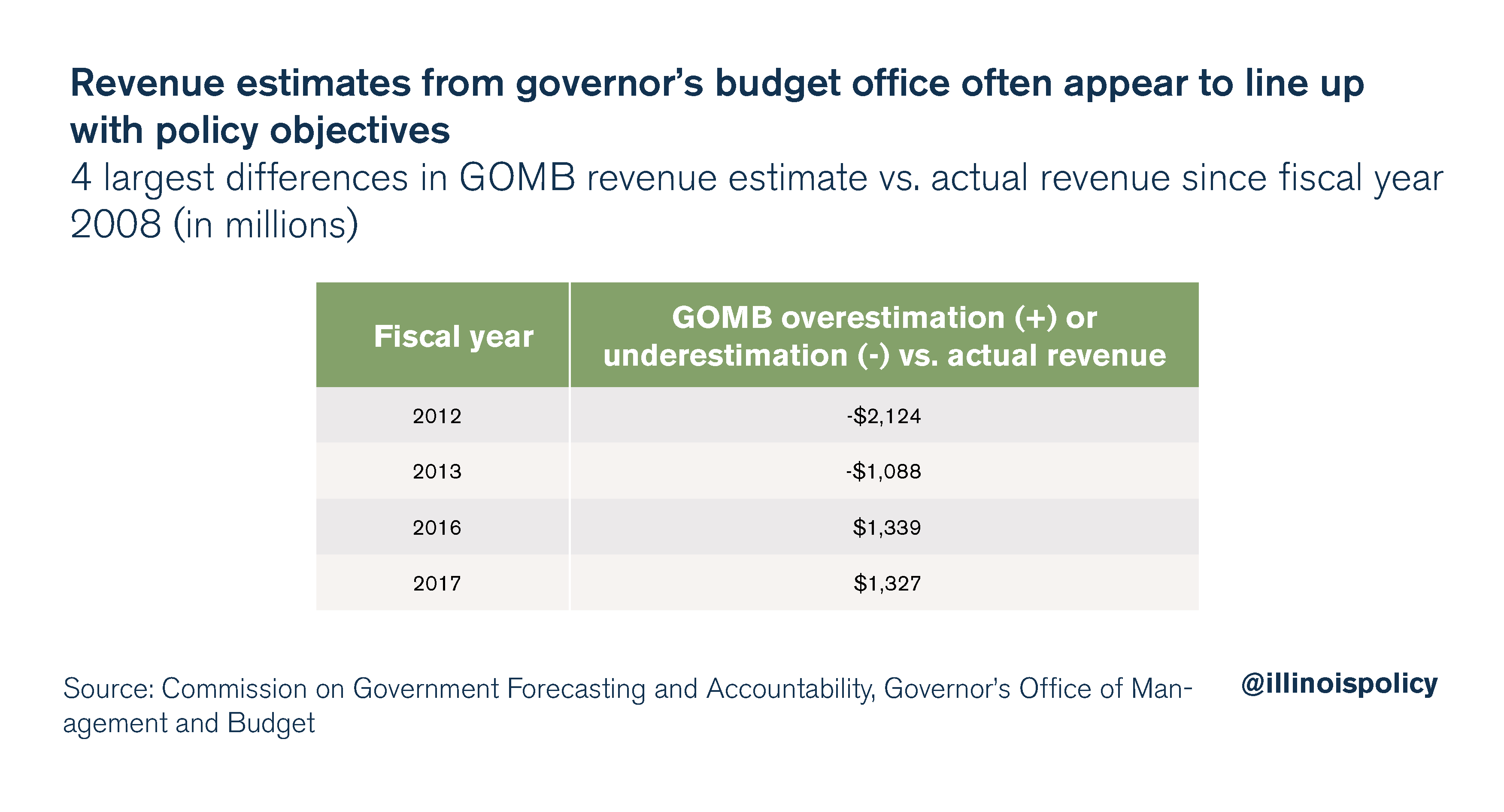

Revenue estimates from the governor’s budget office often appear to line up with policy objectives

For his 2013 budget proposal, while advocating for extending or making permanent the 2011 income tax increase, former Gov. Pat Quinn went so far as to propose two budgets to the General Assembly: a “recommended” budget including an extension of the tax increase and a “not recommended” budget that purported to show the deep cuts that would be necessary if the tax increase were allowed to expire.

In other words, an underestimation of revenue from his budget office would suit Quinn’s policy goals by making an extension of the tax increase seem necessary. Indeed, his fiscal year 2012 and 2013 revenue estimates were short by about $2 billion and $1 billion, respectively.

In 2016, as the newly elected governor, Rauner was trying to balance the state budget without advocating for tax increases. The more revenue the state was expected to bring in, the easier this task would be. Sure enough, GOMB estimates for fiscal year 2016 and 2017 overestimated revenue by about $1.3 billion each.

This pattern appears remarkably similar to the hypothetical situation discussed earlier, in which Democrats and Republicans use revenue estimates to further their own political ends.65

Only the analysts and decision-makers within the governor’s office can say for sure what their motivations were for using different assumptions in their revenue forecasting, but from the outside looking in, the estimates seem to conveniently line up with each governor’s policy goals.

Both COGFA and GOMB are likely doing their best. However, revenue estimating is a mixture of art and science that is impossible to get right. According to the National Association of State Budget Officers, 33 states underestimated revenue in 2017, 13 overestimated revenue and only four were reasonably on target.66

In fact, Illinois may be a state where it is particularly hard to do economic projections. Economists have found that short-term elasticities for taxes in Illinois were higher than the U.S. average, meaning revenues are more vulnerable to economic shocks.67 A report from the Rockefeller Institute found that the absolute value of percentage forecasting errors was higher in Illinois than the national average using a “naïve” or simple model, suggesting that the task is more difficult here.68

The lesson is not that the staff at COGFA and GOMB are bad at their jobs, but rather that relying on revenue estimates for budget planning will cause uncertainty no matter who is running the numbers.

A paltry rainy-day fund and bad tax policy make Illinois vulnerable to recession

Poor savings habits

State lawmakers created the Illinois Budget Stabilization fund in 2002 “for the purpose of reducing the need for future tax increases, maintaining the highest possible bond rating, reducing the need for short term borrowing, providing available resources to meet State obligations whenever casual deficits or failures in revenue occur, and providing the means of addressing budgetary shortfalls.”69

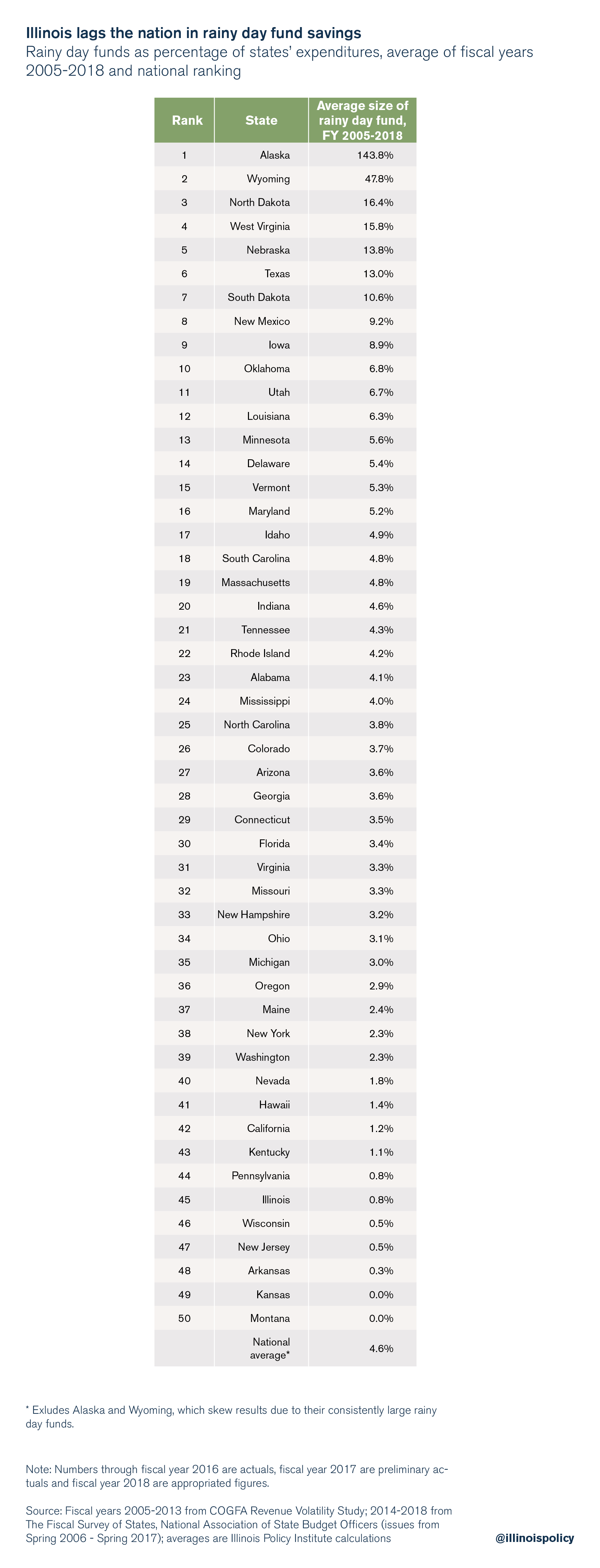

It has never been adequately funded. In fact, Illinois ranks 45th among states for rainy day savings as a percentage of expenditures from 2005 to 2018.

The average size of states’ rainy day funds since 2005 is 4.6 percent of expenditures, excluding the outliers of Alaska and Wyoming. The average size of Illinois’ rainy day fund is less than 1 percent of expenditures over the same time period. Going into the 2019 fiscal year, the state essentially has no savings at all, with less than $100,000 in the account as of June 7, 2018.70

The fiscal year 2017 stopgap budget both swept the rainy day fund and changed Illinois law so that the fund did not have to be repaid.71 The statute currently creates a goal of 5 percent funding as a percentage of revenue but lacks adequate procedures for withdrawals and deposits to make that a reality.72

Public economists comparing all 50 states rank Illinois’ rainy day fund withdrawal rules as low as possible on a scale of 1 to 4.73 Specifically, Illinois has no statutory formula for withdrawing funds and allows lawmakers to dip into the savings through a simple appropriation process.

Both COGFA and the Civic Federation have recommended Illinois implement a plan to preserve 10 percent of revenues in a rainy-day fund.74 However, this amount may be excessive and cause taxpayers to ask why additional revenue cannot be returned to them in tax relief.

A volatile tax portfolio

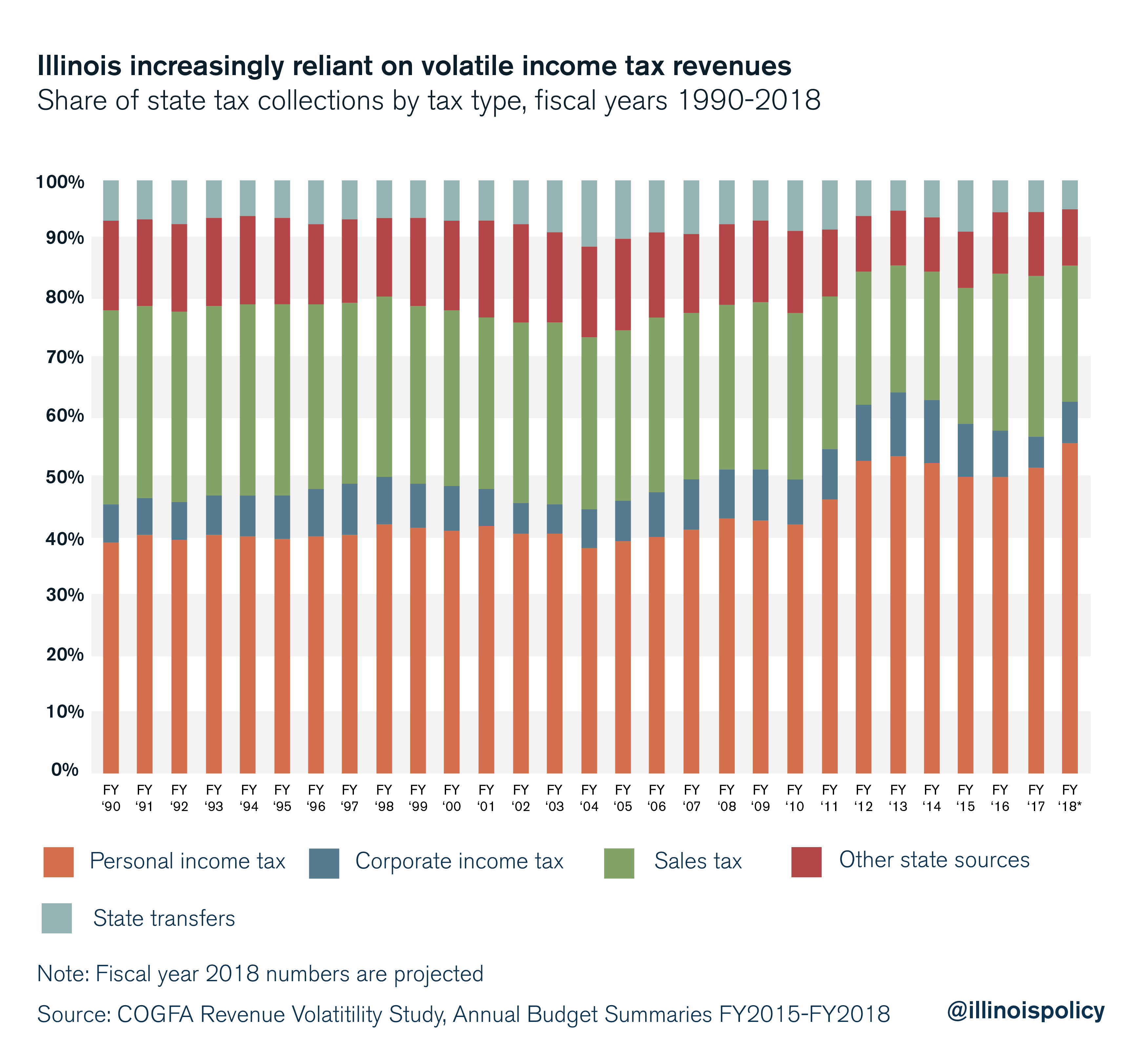

Additionally, Illinois is moving in the wrong direction with regard to its tax portfolio. This can be seen by looking at the “big three” taxes that account for most state revenue. In 1990, Illinois collected just under 39 percent of total state revenue from personal income taxes, just under 33 percent from sales taxes, and only about 6.5 percent from the corporate income tax. Over the 20-year period from 1990 to 2010, prior to the 2011 income tax hike, these averages were 40.5 percent, 30.3 percent, and 7.1 percent respectively.75

From 2011 to 2018, Illinois has relied more on personal and corporate income taxes to fund state government. Remember that these are the most elastic, and volatile, sources of revenue for a state. Since the 2011 tax hike, the personal income tax has increased to an average of 51.6 percent of state tax collections, while corporate income taxes averaged 8.5 percent. Just 23.8 percent came from sales taxes.76

With an economy that is harder to predict and more volatile than average, and savings far below the norm, Illinois is particularly vulnerable to fiscal crisis during the next national recession.

Dedicated fund sweeps and short-term borrowing for operations undermine sustainability of government spending

Illinois also violates sound budgeting principles by siphoning off money from dedicated funds and borrowing to fund ordinary government operations. The Volcker Alliance has noted, “A basic tenet of budgeting is that one-time revenues should fund only one-time expenditures and that recurring revenues should cover obligations that come due every year.”77 Put differently, the state should incur debt only for specific purposes and usually only when the incurrence of debt has a long-term return on investment, such as with certain capital improvement projects.

Spending on the operating budget should be entirely financed through annual recurring revenues, such as the big three taxes. Unfortunately, due to Illinois policymakers’ inability to control spending, the state has a habit of sweeping funds intended for dedicated purposes and issuing bonds to pay for pensions or operating costs.

Lawmakers have transferred money out of the budget stabilization fund every year since 2003. In all but five of the last 15 years, the state has either borrowed from state funds, issued bonds or swept funds to pay for operations. The difference between a fund sweep and borrowing from a fund is that sweeps do not have to be paid back. However, the state often “forgives” its borrowing from special funds and decides not to pay them back anyway.

According to Truth in Accounting, Illinois has over 600 special funds.78 Special funds often have dedicated revenue sources apart from the general funds budget, such as user fees, licensing fees or regulatory penalties. While not all of these funds are well-managed or necessary, many are self-funding and productive.

For example, the Mental Health Fund is financed by payments from patients and persons responsible for care and treatment. Money from the fund is supposed to be used to advance mental health facilities and services in the state. The General Assembly swept over $1.1 million out of this fund in fiscal year 2018.79

Borrowing or transferring money out of special funds is a crutch used to avoid reducing spending to a long term sustainable level.

The recent “safe roads” amendment to the Illinois Constitution will prevent lawmakers from sweeping transportation funds to use for anything other than transportation costs, taking away a favorite piggy-bank lawmakers used to raid.80 While transportation dollars should not receive special constitutional consideration over other essential state spending,81 efforts to constrain lawmakers’ ability to rely on spending gimmicks are good in principle. However, this should be done without creating a patchwork of narrow exemptions in constitutional law.

Similarly, the state issued bonds in 2003, 2010 and 2011 to pay for annual pension costs. This $17.2 billion in borrowing will cost $25.8 billion to pay off in the long term.82 This practice decreased public transparency around pension payments, while serving as a way to avoid reforming unsustainable pensions.

While official reporting from COGFA shows pensions account for 18 percent of all general funds spending, the total is actually higher since debt payments on the pension obligation bonds are included in the “debt service” category rather than the pensions category. GOMB reports that the pension obligation payment for fiscal year 2018 was $1.579 billion. If this amount is deducted from the “debt service” category and added to the pension category, total state spending on pensions for fiscal year 2018 rises to 22 percent.83

In addition to putting off tough choices about spending reductions, fund sweeps and borrowing are two reasons Illinois fails on financial transparency – these practices hide the real cost of government from residents and mislead bondholders about the sustainability of spending.

Cash-based budgeting hides the true size of Illinois’ deficits

While Illinois policymakers fail the transparency test in many aspects of budgeting, cash-based budgeting is perhaps the worst culprit behind the opaqueness of the budgeting process.

Official end-of-year cash-based reports show Illinois’ budget has not been balanced since 2001. What many Illinoisans may not know, however, is that the true size of Illinois’ budget deficit each year is even larger than it seems. Through what’s called “cash-based” accounting, lawmakers are able to hide spending by waiting to pay their bills, thus pushing costs onto future generations.84

Under this system, revenues are counted in the year they are received. Meanwhile, expenses are counted only in the year they are paid, not the year they are incurred.

Imagine if a household magically “balanced” its budget each month by not paying the electric bill. That’s the type of behavior cash-based budgeting hides in state government.

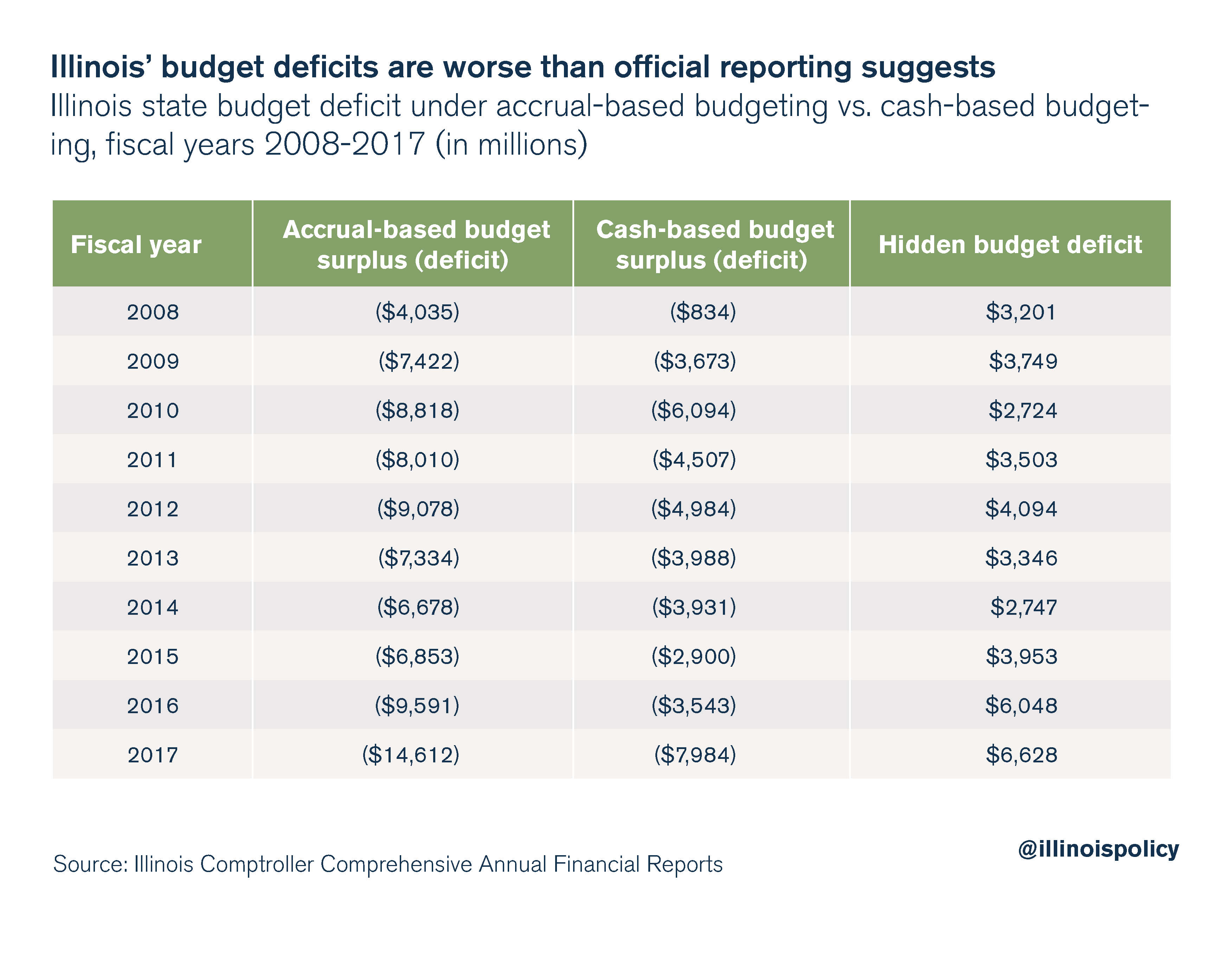

The extent to which this accounting gimmick hides the true cost of Illinois government spending can be seen by comparing Illinois’ cash-based accounting to a system using generally accepted accounting principles, or GAAP. The crucial difference between these two methods is that GAAP includes what’s called “accrual-based” accounting.

When comparing cash-based accounting with accrual-based accounting, it’s clear the state has underreported its true budget deficit by billions of dollars each year. The true budget deficit for fiscal year 2017 alone was at least $6.6 billion worse than official reporting, and lawmakers’ assumptions, suggest.

In addition to the traditional reporting lawmakers use when planning the budget each year, the Illinois comptroller releases a Comprehensive Annual Financial Report, or CAFR, which uses accrual-based accounting. The problem is that the CAFR doesn’t come out until several months after the fiscal year ends, making it useless for the budget planning process. This reveals the futility of a balanced budget amendment that requires balance at the appropriation stage, rather than focusing on end-of-year balance.

National and state policy groups including the Volcker Alliance, the Better Government Association, the Fiscal Futures Project and Truth in Accounting have all suggested Illinois switch to an accrual-based system for budgeting, meaning spending would be counted in the year it was incurred, not the year the bill is paid.

Academic research on the subject is clear that balancing budgets including accruals information, such as the present value of assets and the long-term cost of liabilities, is vital to fiscal sustainability and strong credit.85 Internationally, proponents argue that using accruals information for the budget process improves management of capital stock, illuminates the long-term trajectory of public finances, improves transparency and ensures symmetry with financial reporting that is done on an accruals basis. At least four countries – the United Kingdom, Italy, Australia and New Zealand – use full accruals budgeting.86

While Illinois lawmakers have not adopted this standard for themselves, they have passed laws mandating the use of generally accepted accounting principles for some private entities.87

Including information about unpaid bills, pensions and debt service would go a long way toward improving public transparency and lawmaker planning around the budget.

Solutions to Illinois’ budgeting problems

llinois has been a national embarrassment on budget and tax issues for too long. It is time to give taxpayers and businesses the certainty they need to plan a long-term future in the state.

Lawmakers should immediately enact the following reforms to fix the four key issues with the budget process:

- Replace faulty revenue estimates with a reliable starting point:

- Adopt a spending cap – SJRCA 21 and HJRCA 38 – to improve the accuracy of budget planning and reduce political conflict in negotiations, rather than relying on imperfect revenue estimates for spending planning.

- Revenue estimates should still be required and should statutorily require automatic averaging between COGFA and GOMB estimates, rather than relying on the General Assembly to pass a resolution.

- To address a paltry rainy day fund and volatile taxes, surpluses resulting from the spending cap should be used to do the following:

- Pay down the backlog of unpaid bills.

- Rebuild the Budget Stabilization Fund to at least 5 percent of annual expenditures. Simultaneously, lawmakers should strengthen restrictions on when funds can be withdrawn.

- Cut income tax rates to provide tax relief and improve the predictability of Illinois’ tax portfolio.

- Avoid one-time revenue infusions by limiting lawmakers’ ability to rely on spending gimmicks, without creating a patchwork of constitutional carveouts:

- For example, HJRCA 16 would redefine revenue to exclude debt, refinancing or fund sweeps.

- Avoid issuing bonds to pay for yearly operations or pension costs.

- End bad accounting practices that hide the true size of deficits:

- Adopt accruals-based budgeting so that budget balance is defined by including the present value of assets and the long-term cost of liabilities.

- Strengthen the balanced budget provision of the Illinois Constitution to require end-of-year balance, rather than just prospective balance.

Ultimately, getting Illinois back on the path to fiscal health will require meaningful pension reform and changes to all of the major cost drivers of the budget. But creating a sound budgeting process is a critical step to ensure taxpayers have the transparency and predictability they deserve.

Endnotes

- John O’Connor and Sophia Tareen, “Illinois approves spending plan, ending nation’s longest budget stalemate,” PBS News Hour, July 6, 2017.

- Ted Dabrowski and John Klinger, “Illinois now has the lowest credit rating on record for a US State,” Illinois Policy Institute, June 1, 2017.

- Adam Schuster, “Illinois bonds once again rated just above junk,” Illinois Policy Institute, April 10, 2018.

- Civic Federation, “How Will Illinois Fund Its Infrastructure Needs?” January 26, 2018.

- Adam Schuster, “Illinois General Assembly passes state budget out of balance by as much as $1.5B,” Illinois Policy Institute, May 31, 2018.

- Adam Schuster, “Illinois bonds once again rated just above junk.”

- Sunny Oh, “Here’s why Illinois’ new budget isn’t impressing ratings firms,” Market Watch, June 7, 2018.

- Adam Schuster, “Will Illinois pass a budget this year?” Illinois Policy Institute, April 20, 2018.

- Ill. Const. art. VIII, § 2(b).

- Orphe Divounguy, Bryce Hill, and Joe Tabor, “Special report: Why Illinois needs a spending cap,” Illinois Policy Institute.

- Jonathan Bydlak and Corie Whalen, “Remember Milton Friedman: Spending is taxing,” Real Clear Policy, December 17, 2012.

- Orphe Divounguy, Bryce Hill, and Joe Tabor, “Why the 2017 tax hikes will harm Illinois’ economy,” Illinois Policy Institute.

- Orphe Divounguy, “Land of lagging: Illinois’ sluggish economy and lawmakers’ tax hike treachery,” Illinois Policy Institute, January 24, 2018.

- Orphe Divounguy, “What’s dragging down Illinois’ economy,” Illinois Policy Institute, December 20, 2017.

- Austin Berg, “Census: Illinois loses title of 5th-largest state to Pennsylvania,” Illinois Policy Institute, December 20, 2017.

- Orphe Divounguy, “September jobs report: Declining job prospects and a shrinking labor force,” Illinois Policy Institute, October 20, 2017.

- Paul Simon Public Policy Institute, “Illinois voters ask: Should I stay or should I go?” October 10, 2016.

- Orphe Divounguy, Bryce Hill, and Joe Tabor, “False promises, real harm: Why Illinoisans should reject a progressive income tax,” Illinois Policy Institute, Spring 2018.

- Orphe Divounguy, Bryce Hill, and Joe Tabor, “False promises, real harm: Why Illinoisans should reject a progressive income tax,” Illinois Policy Institute, May 3, 2018.

- Jared Walczak, “Proposed Illinois tax hikes are a regional outlier,” Tax Foundation, May 3, 2018.

- Antonio Fatás and Ilian Mihov, “The macroeconomic effects of fiscal rules in the US states,” Journal of Public Economics, 90 (1-2) (2006): 101-117.

- Danish Murtaza, “Three ways to improve Illinois’ budget process,” Better Government Association, February 15, 2018.

- See multiple: Donald J. Boyd and Lucy Dadayan, “State Tax Revenue Forecasting Accuracy,” Rockefeller Institute, 2014; Emily Franklin, Carolyn Bourdeaux, and Alex Hathaway, “State revenue forecasting practices: Accuracy, transparency, and political acceptance,” Volcker Alliance Project, 2017.

- See multiple: Stuart I. Bretschneider, Wilpen L. Gorr, Gloria Grizzle, and Earle Klay, “Political and organizational influences on the accuracy of forecasting state government revenues,” International Journal of Forecasting, 5 (1989): 307-319; Yuhua Qiao, “Use of Consensus Forecasting in U.S. State Governments” in, Government Budget Forecasting: Theory and Practice, 402-408 (2008); Robert T. Clemen, “Combining forecasts: A review and annotated bibliography,” International Journal of Forecasting, 5 (1989): 559-583.

- Bretschneider et al. 1989, p. 311.

- See multiple: John Ellwood, “The great expectation: The Congressional budget process in an age of decentralization,” in: Lawrence C. Dodd and Joe B. Oppenheimer, eds., Congress Reconsidered, 3rd ed. (Congressional Quarterly Press, Washington, D.C.); Mark S. Kamlet and David C. Mowery, “The first decade of the Congressional budget act: Legislative imitation and adaptation in budgeting”, Policy Sciences, 18, (1985): 313-334; Mark S. Kamlet and David C. Mowery and T. Su, “Whom do you trust? An analysis of executive and Congressional economic forecasts,” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 6, (1987): 365-384.

- William E. Klay and Gloria A. Grizzle, “Forecasting state revenues: Expanding the dimensions of the budgetary forecasting research,” Public Budgeting & Financial Management, 1992; secondary citations available online.

- Vernon Dale Jones, Stuart Bretschneider, and Wilpen L. Gorr, “Organizational Pressures on Forecast Evaluation: Managerial, Political, and Procedural Influences,” Journal of Forecasting, 16(4) (1998): 241-254.

- Bretschneider et al., 1989.

- William R. Voorrhees, “More Is Better: Consensual Forecasting and State Revenue Forecast Error,” International Journal of Public Administration, 27 (8-9) (2004): 651-671.

- Boyd and Dadayan, 2014.

- Bretschneider et al., 1989.

- See multiple: Randall G. Holcombe and Russel S. Sobel, Growth and Variability in State Tax Revenue: An Anatomy of State Fiscal Crises, (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1997); Russell S. Sobel and Gary A. Wagner, “Cyclical Variability in State Government Revenue: Can Tax Reform Reduce It?” State Tax Notes, 29(8) (August 2003): 569-576; Gary C. Cornia and Ray D. Nelson, 2010, “State tax revenue growth and volatility,” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, Regional Economic Development, 6(1): 23-58.

- See multiple: Richard Mattoon and Leslie McGranahan, “Revenue Bubbles and Structural Deficits: What’s a state to do?” Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, 2012; Boyd and Dadayan 2014; Russell S. Sobel and Randall G. Holcombe, “Measuring the Growth and Variability of Tax Bases Over the Business Cycle,” National Tax Journal 49(4) (1996): 535-552; Alison R. Felix, “The Growth and Volatility of State Tax Revenue Sources in the Tenth District,” Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City Economic Review, 93(3) (2008): 63-88.

- See multiple: Cornia and Nelson, 2010; Randall G. Holcombe, and Russel S. Sobel, 1997.

- See multiple: Sobel and Wagner, 2003; Dye, Richard F. and Therese J. McGuire, “Growth and variability of state individual income and general sales taxes.” National Tax Journal, 44(1) (1991): 55-66.

- Matoon and McGranahan, 2012; Boyd and Dadayan, 2014

- Fred Thompson and Bruce Gates, “Betting on the Future with a Cloudy Crystal Ball: Revenue Forecasting, Financial Theory, and Budgets – An Expanded Treatment,” Public Administration Review, 67(5) (2007).

- Boyd and Dadayan, 2014, p. ii

- Thompson and Gates, 2007; Boyd and Dadayan, 2014.

- Holcombe and Sobel, 1997; Sobel and Wagner, 2003; Felix, 2008.

- See for example: Henning Bohn and Robert P. Inman, “Balanced-budget rules and public deficits: evidence from the U.S. states,” Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy, 45 (1996): 13-76; Gary A. Wagner and Erick M. Elder, “The role of budget stabilization funds in smoothing government expenditures over the business cycle,” Public Finance Review, 33(4) (2005); Fatás and Mikov, 2006; Thompson and Gates, 2007; Mattoon and McGranahan, 2012; Boyd and Dadayan, 2014.

- Richard Dye, David Merriman, and Andrew Crosby, “Improving Budget Practices in Illinois,” The Fiscal Futures Project, 2015; Murtaza 2018, Better Government Association.

- Gary C. Cornia and Ray D. Nelson, “Rainy Day Funds and Value at Risk,” Conference on ‘State Fiscal Crises: Causes, Consequences, and Solutions,” Urban Institute, Brookings Institution, Kellog School of Management and Institute for Policy Research, April 3, 2003.

- Saeid Mahdavi, “Bohn’s Test of Fiscal Sustainability of the American State Governments,” Southern Economic Journal, 80(4) (2014): 1028-1054.

- Fatás and Mihov, 2006; Thompson and Gates, 2007.

- National Conference of State Legislatures, “State balanced budget requirements.”

- Kitty Toll, “Balanced budget is a Vermont tradition,” May 30, 2015.

- Michael U. Dothan and Fred Thompson, “A Better Budget Rule,” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 28 (3): 463-478.

- James Poterba, “Capital Budgets, Borrowing Rules, and State Capital Spending,” Journal of Public Economics, 56 (1992): 165-187.

- See multiple: James D. Hamilton and Marjorie Flavin, “On the Limitations of Government Borrowing: A Framework for Empirical Testing,” American Economic Review, 76(4) (1986): 808-819; Thompson and Gates, 2007.

- Bohn and Inman, 1996.

- National Conference of State Legislatures, “State balanced budget requirements.”

- Matthew Mitchell,, “T.E.L. it like it is: Do state tax and expenditure limits actually limit spending?” Mercatus Center, 10-71 (2010).

- Vincent Caruso, “Illinois flunks new nationwide fiscal report card,” Illinois Policy Institute. November 15, 2017.

- 25 ILCS 155/4; 20 ILCS 3005/2.1.

- Standard disclosed to Illinois Policy Institute via email.

- COGFA, “FY 2019 Economic Forecast and Revenue Estimate and FY 2018 Revenue Update,” February 27, 2018.

- Fiscal Year 2019 proposed operating budget, February 14, 2018.

- GOMB, State of Illinois General Obligation Bonds, Series of May 2018, April 13, 2018.

- Adam Schuster, “Illinois bonds once again rated just above junk.”

- Adam Schuster, “Senate President John Cullerton says Illinois doesn’t need a revenue estimate,” Illinois Policy Institute, May 9, 2018.

- 25 ILCS 155/4; Ill. Const. art. VIII, § 2(b).

- Lisa Madigan, “APPROPRIATIONS: Durational Requirements of State Budget; Legislature’s Appropriation Authority,” Office of the Attorney General: State of Illinois, May 27, 2014.

- Bretschneider et al 1989, 311.

- National Association of State Budget Officers, “Spring 2017 Fiscal Survey of States,” June 15, 2017.

- Holcombe and Sobel, 1997.

- Boyd and Dadayan, 2014.

- House Bill 3493, 92nd Illinois General Assembly.

- Office of the Illinois Comptroller, Budget Stabilization Fund.

- Public Act 099-0523.

- 30 ILCS 122/15.

- Fatás and Mihov, 2006.

- COGFA Revenue Volatility Study, p. 75; Civic Federation FY 2019 Recommended Operating and Capital Budgets, May 9, 2018: p. 12.

- Illinois Policy Institute calculations based on COGFA data.

- Ibid.

- The Volcker Alliance. 2017. “Truth and Integrity in State Budgeting: What is the reality?”

- Sheila Weinberg, “Illinois’ special funds,” Truth in Accounting, October 12, 2017.

- COGFA Budget Summary 2018.

- Truth in Accounting, “Illinois’ Special Funds.”

- Ted Dabrowski, “Transportation ‘lockbox’ amendment is a bad idea,” Illinois Policy Institute, October 27, 2016.

- Illinois Policy Institute, “Illinois Pension Bonds: The other $26 billion obligation you shouldn’t ignore.”

- Illinois Policy Institute calculations based on COGFA and GOMB data.

- Dye et al., 2015, “Improving Budgetary Practices in Illinois.”

- Hamilton and Flavin, 1985; Thompson and Gates, 2007; Mahdavi, 2014.

- Jón R. Blöndal, “Issues in Accrual Budgeting,” OECD Journal on Budgeting, 4(1) (2004).

- 765 ILCS 160.