CPS pensions: From retirement security to political slush fund

By Ted Dabrowski, John Klingner

Download Report

CPS pensions: From retirement security to political slush fund

By Ted Dabrowski, John Klingner

Download Report

Introduction

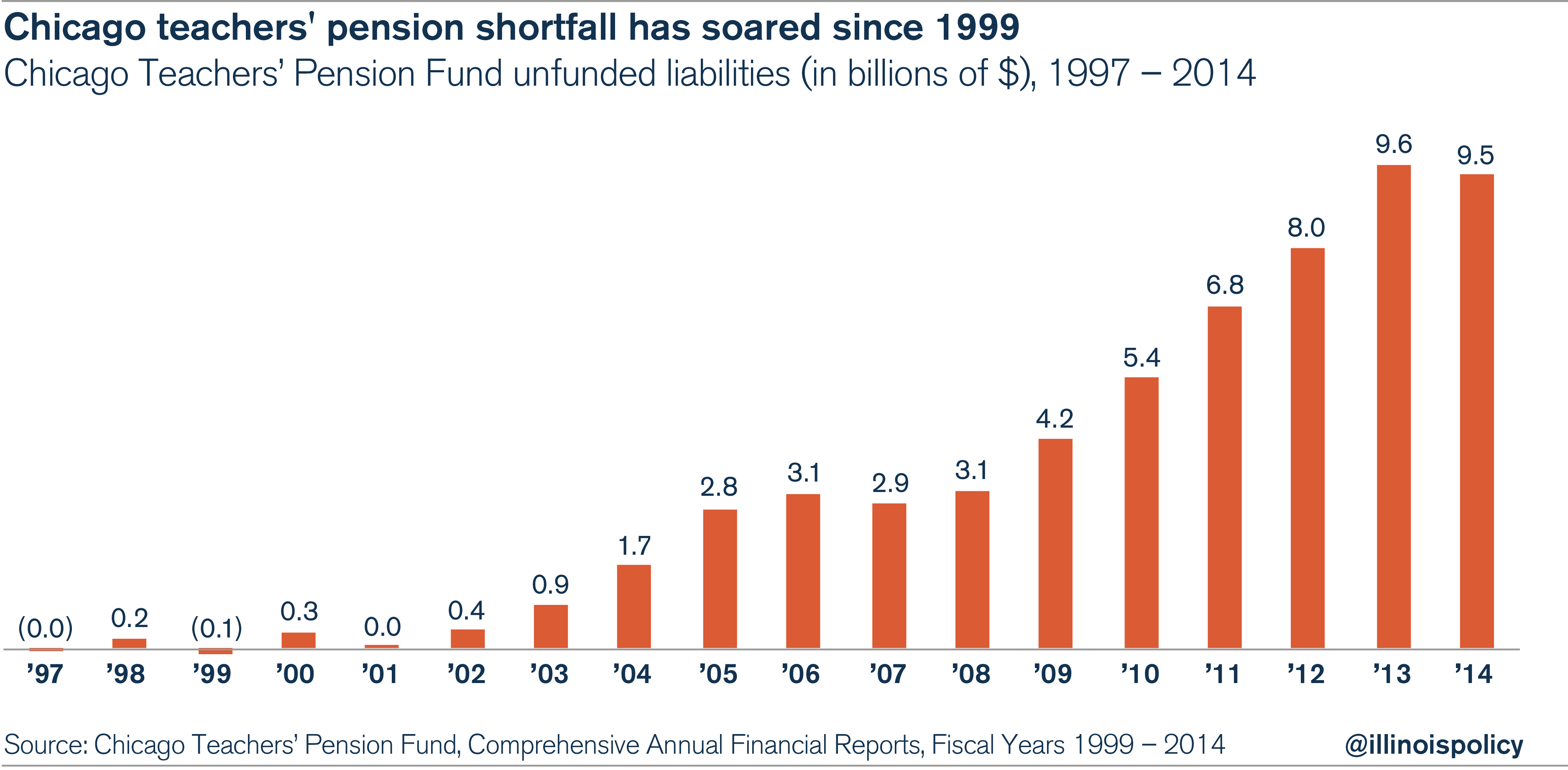

Chicago Public Schools, or CPS, is facing a pension shortfall of $9.5 billion, multiyear, billion-dollar deficits and a credit rating that’s been downgraded to junk. This crisis is arguably the best example of how Illinois politicians use and abuse pensions, turning what is meant to provide government workers with retirement security into a political slush fund.

From pension spiking and pickups to double dipping and skipped payments, pension systems have been co-opted by the corruption and political trading for which Chicago politicians are famous.

The current narrative is that historically CPS didn’t have enough money to fund both teacher pensions and the classroom – that it had no choice but to shortchange pensions.

But a close review of the school district’s finances over the past 20 years finds that revenues never were the issue; Illinois and Chicago taxpayers contributed more than enough money to pay for both, had the funds just been properly managed.

In fact, taxpayer-provided CPS revenue has more than doubled to $5.3 billion since 1997. When measured in per-student terms, CPS revenues grew at more than 1.5 times the rate of inflation during that time period. Despite those growing revenues, CPS leaders have brought the teachers’ pension fund to the brink of insolvency. Now they’re counting on taxpayers to clean up the mess; but taxpayers shouldn’t be forced to bail out a retirement system that’s been corrupted into a political tool.1

What caused the crisis

CPS’ problems began in 1995 when politicians started treating the pension system as a slush fund, draining billions of dollars from teachers’ retirements for political benefit.

CPS officials – with the consent of the General Assembly – enacted a 10-year “pension holiday” that diverted more than $1.5 billion in taxpayer dollars away from pensions and toward school operations, most notably to salaries.2

In 1999, the system was fully funded. But by 2006, those skipped pension contributions coupled with a weak stock market created a $3.1 billion shortfall.3

Even though the pension holiday added billions of dollars of debt to the pension fund, CPS resorted to the same pension-holiday scheme again in 2010, diverting yet another $1.3 billion from teacher pensions over a three-year period.

The results of that mismanagement were catastrophic: By 2013, the teacher-pension shortfall had jumped to $9.6 billion, and the fund had just half the money needed to pay out future teacher pension benefits.

It’s odd that the Chicago Teachers Union, or CTU, did not squash the pension holidays to protect its members’ retirement security. Perhaps it had to do with the fact that the money diverted from pensions allowed CTU members to receive consistent pay increases averaging 4.2 percent per year from 1998 to 2012.4

Those raises, which outpaced inflation, contributed to Chicago teachers becoming the highest-paid educators among the nation’s 10 largest school districts.5

Not only did those higher salaries drive up costs for CPS, they also widened the pension shortfall.

Because salaries determine future pensions, the pay increases helped boost benefits at the unsustainable growth rate of 6 percent annually over a 17-year period.

Had pension benefits grown at a more modest rate, the pension shortfall would be $4 billion to $6 billion less than it is today.6

The political scheming of the past two decades has led to the devastation of a school district meant to educate Chicago’s children, the destruction of the job and retirement security of the teachers who educate them, and the contempt of the taxpayers who fund it all.

If pension funding had simply gone where it belonged, those billions of taxpayer dollars could have funded teacher pensions while also allowing for a modest growth in teacher salaries.

Instead, politicians squandered the money – and now they’re coming back for more.

More tax dollars won’t fix a broken system

City leaders are calling on Chicagoans to pay billions more in property and other taxes to clean up their mess.

Some claim pensions need a funding guarantee and other controls to ensure the political deals of the last 20 years don’t happen again.

But pension systems are inherently political, opaque and void of accountability. As long as politicians maintain control over pensions, they’ll always find ways to exploit them and pass on the costs to taxpayers.

Instead, teachers and taxpayers deserve a real funding guarantee in the form of self-managed plans such as 401(k)s – owned and controlled by teachers – which politicians can’t touch.

That would mean real retirement security for teachers and the ability of taxpayers to finally hold politicians accountable.

Until then, CPS doesn’t deserve another penny from taxpayers.

What's driving the CPS financial crisis and the teachers' pension crisis

Both CPS and the Chicago Teachers’ Pension Fund, or CTPF, are in financial crisis. CTPF is missing half of the money it needs to provide for teacher retirements.

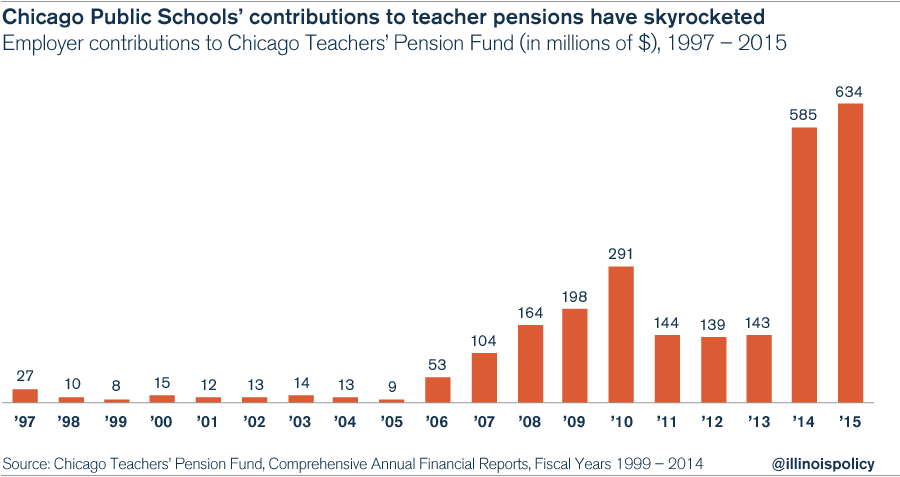

At the same time, the $634 million shortfall in pension contributions from CPS this year has caused the district severe financial stress. CPS is faced with a $1 billion budget deficit and is looking to increase taxes, borrow more than $1 billion, and cut teachers, schools and programs in order to stabilize its budget.7

According to Mayor Rahm Emanuel, the lack of revenue from Springfield is responsible for the current crisis. He and other city leaders say that CPS’ financial crisis would not exist if Springfield had provided “fair funding” to the district.8

However, an analysis of the financial history of both CPS and CTPF, shows that it’s the political exploitation of teacher retirements through underfunding and extra benefits that has caused the current crisis, not a lack of revenue.

CTPF’s near insolvency and the financial pressure its collapse is having on CPS are a direct result of politicians treating pensions as a slush fund rather than as a retirement guarantee for teachers.

Teachers’ pension fund: From fully funded to $9.5 billion shortfall

In 1999, the Chicago Teachers’ Pension Fund was fully funded and considered healthy according to the system’s actuaries.

That’s in stark contrast with the crisis CTPF faces today. The system’s unfunded liability has jumped to nearly $10 billion in the last decade, putting teachers’ retirements at risk and taxpayers on the hook.

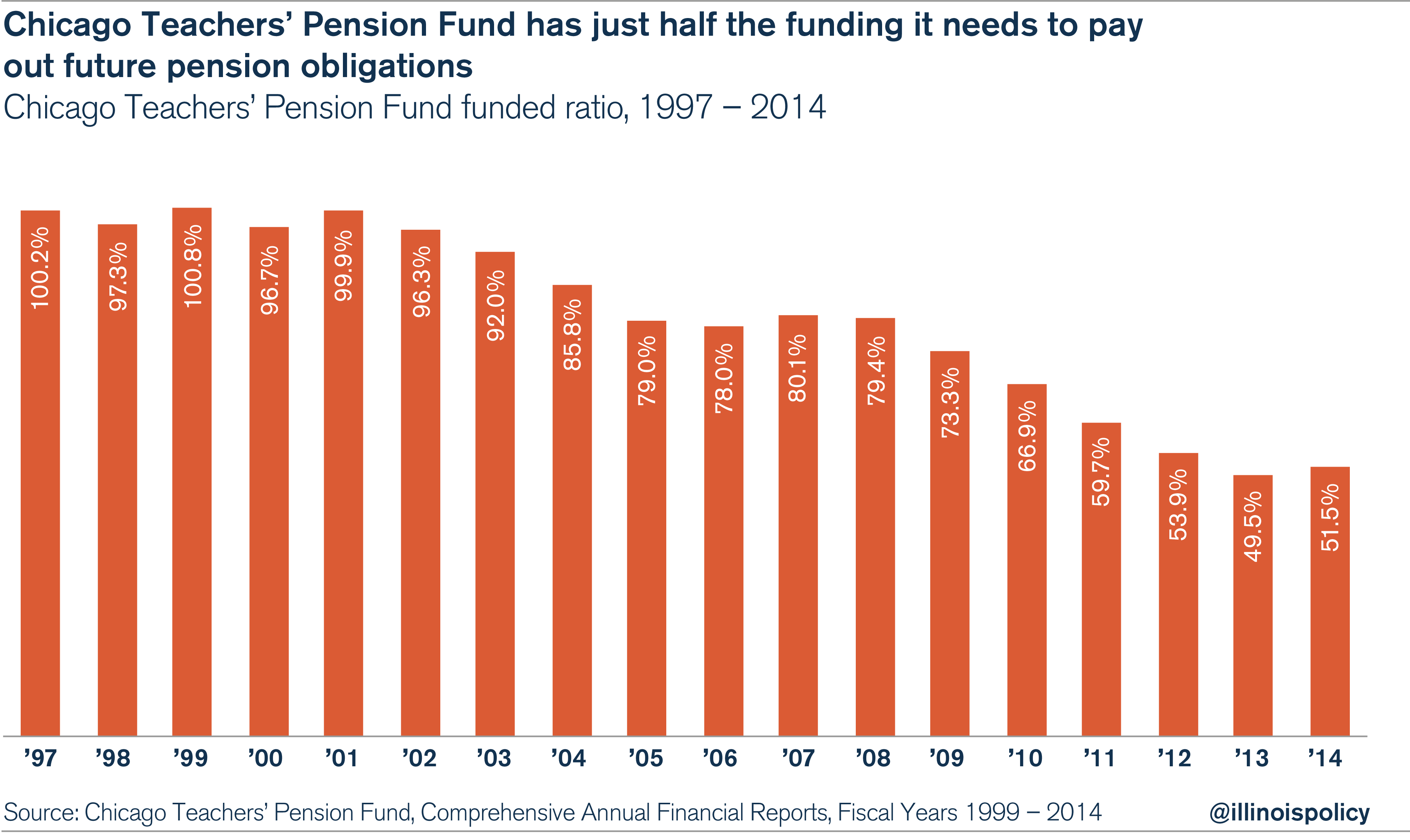

CTPF’s funding ratio has collapsed from 100 percent to 52 percent in just 13 years. It now has just half the funding it needs to pay out its future retirement obligations. By any private-sector measure, the fund is already bankrupt.9

The pension shortfall has caused the amount of contributions CTPF needs to jump by hundreds of millions of dollars, placing significant fiscal stress on CPS’ finances.

In fact, the contribution CPS needs to make to pensions is the largest portion of the district’s projected billion-dollar annual deficits. To close its fiscal gap, CPS is looking to increase taxes, borrow more than $1 billion, fire teachers, close schools and cut programs. CPS’ financial situation has worsened to the point where Moody’s Investors Service, S&P Ratings Services and Fitch Ratings have downgraded the district’s bonds to junk bond status.10

However, this crisis does not derive from a lack of revenue at CPS. Instead, the origins of the crisis can be traced back to several bad, short-sighted political decisions made by the district’s leaders.

The following four factors created the current crisis.

1. CPS officials made decisions that were politically beneficial in the short term, but yielded disastrous long-term consequences.

Like most financial collapses, this crisis stems from a series of poor decisions that were politically advantageous at the time. CPS leaders and administrators, CTU leaders and the General Assembly created the current crisis by treating teachers’ retirements as a political tool and a slush fund, redirecting billions of dollars away from pensions toward other expenses.

Pickups and pension “holidays” in particular contributed heavily to the current crisis.

CPS “picks up” majority of teachers’ employee contributions

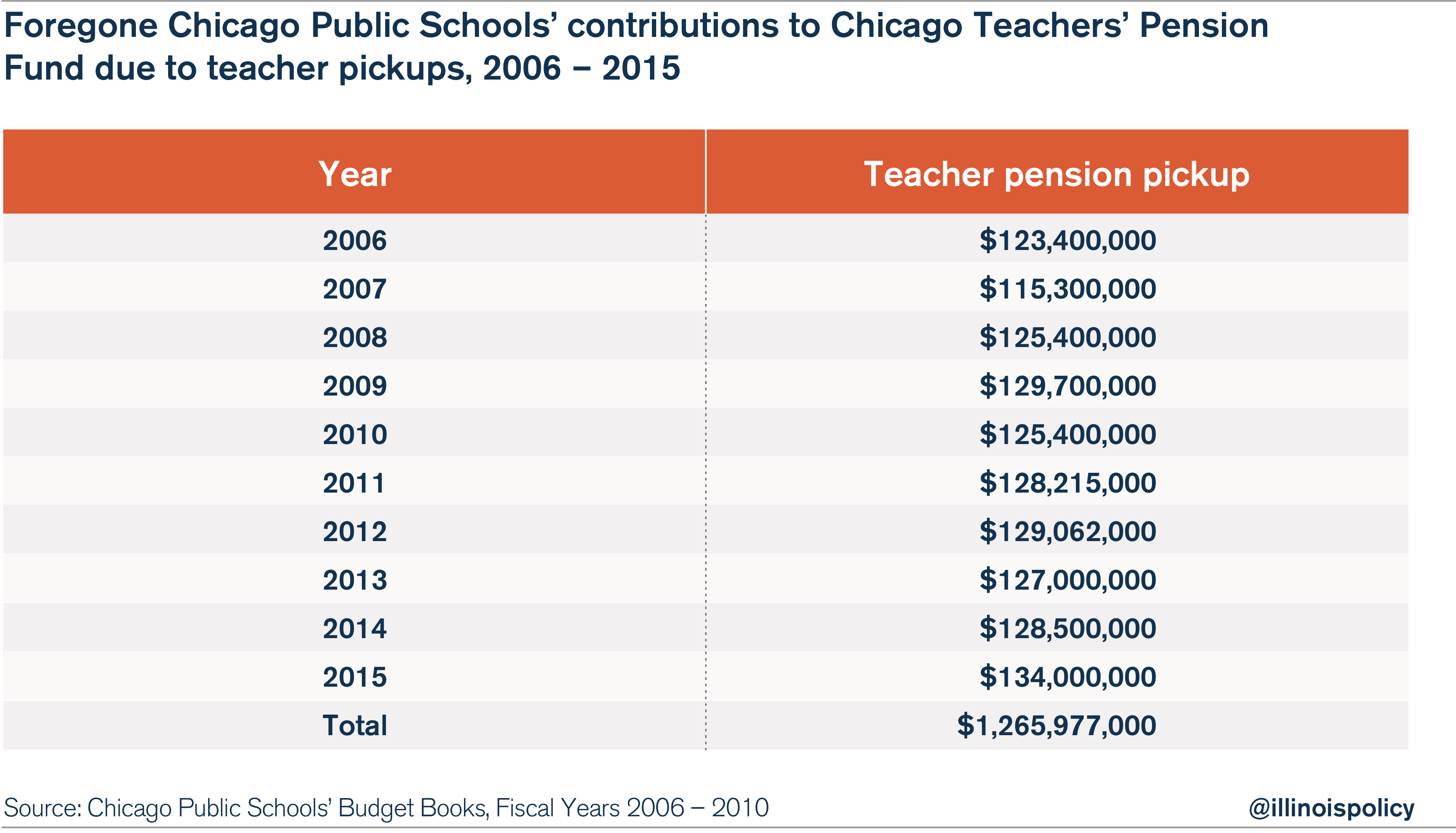

In 1981, as part of contract negotiations with the CTU, CPS agreed to pay, or “pick up,” a majority of what Chicago teachers were legally required to contribute toward their pensions in exchange for the teachers foregoing raises during the term of the contract.11

In other words, teachers were no longer required to pay a majority of their own pension contributions.

Since then, CPS has been diverting operating revenues equivalent to 7 percent of its total teacher payroll to pay for the teachers’ required pension contributions. Teachers still contribute an additional 2 percent of their salaries themselves, which constitutes the employee contributions.

CPS has spent more than $1.2 billion over the last decade covering the cost of teacher pickups. In 2014 alone, the practice cost CPS over $130 million.12,13

Had teachers made their own pension contributions, CPS could have increased the employer’s contribution by $1.26 billion. Higher total contributions would have kept the unfunded liability down, leaving the pension system far healthier.

Instead, CPS officials continue to pick up the majority of the employee contribution, even though only 1 percent of the teachers who were employed in 1981 and were part of that contract negotiation are still employed by CPS today.14

CPS took “holidays” from paying its pension obligations

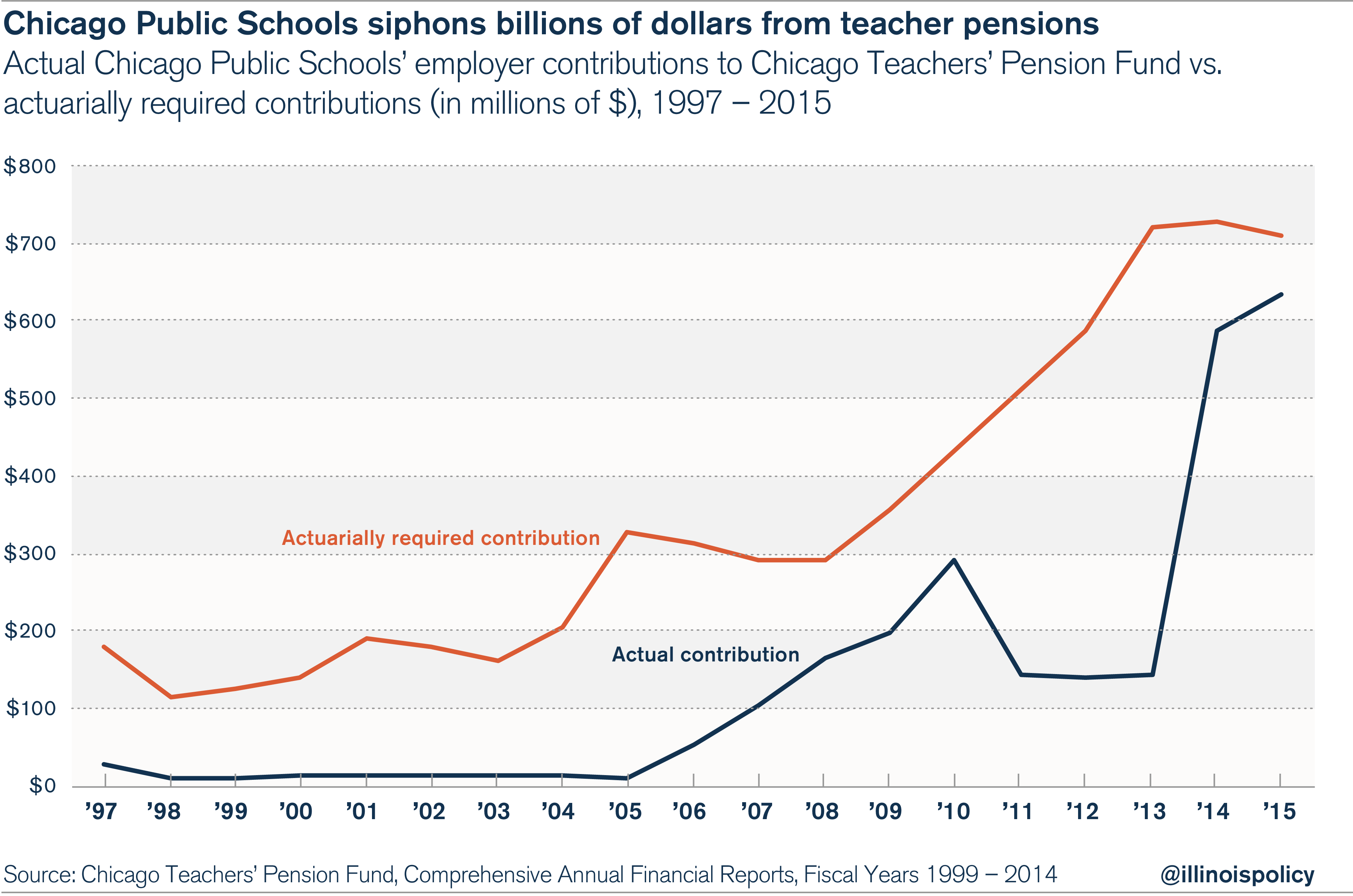

In 1995 and again in 2010, CPS requested, and the General Assembly granted, what are now known as “pension holidays.” Those holidays allowed CPS to avoid making its full required pension contribution to CTPF, setting the stage for the current crisis.

The first holiday, which lasted from 1995 to 2006, allowed CPS to effectively stop making any contributions to the pension plan. Over the course of a decade, more than $1.5 billion of taxpayer money that should have been paid into the fund was diverted toward other CPS operational spending.15

For the first several years of the pension holiday, the fund experienced little trouble. Investment returns, fueled by the dot-com bubble, managed to fill the pension system’s coffers. In fact, in 1997 and 1999, CTPF was fully funded according to the fund’s actuaries.16

But funding problems began when the dot-com bubble burst in 2001. The weak stock market meant the fund’s investment returns could no longer make up for the skipped pension contributions.

The first pension holiday expired in 2006, when the funded ratio of the pension plan fell below 90 percent, and the fund’s shortfall exceeded $3 billion. CPS began making contributions again, but not at the level needed to return CTPF to 100-percent funding.

The Great Recession of 2008 took an even greater toll on teacher pensions. By 2010, the funding ratio had collapsed to 67 percent, and the fund’s shortfall had grown to $5.4 billion.

But rather than shore up the pension fund, CPS requested yet another pension holiday in 2010. With the General Assembly’s approval, CPS went on to divert another $1.3 billion from teachers’ pensions from 2011 to 2013.17

Such mismanagement and shortsighted decision-making have resulted in fiscal calamity for CPS and its teachers’ pensions. Pension pickups and holidays shorted CTPF by more than $5 billion, destroying teachers’ retirement security and displaying a total disregard for the taxpayers who had supplied more than enough funding for Chicago education.

2. CPS had enough revenue to fund pensions and classrooms – but officials squandered it.

The current narrative, as told by school and union officials, is that CPS didn’t have enough money to fund both teacher pensions and the classroom – that it had no choice but to shortchange pensions.18

The implication is that taxpayers didn’t do their part. And with the crisis facing the school district and its pension plan, city leaders argue that taxpayers need to put up even more money.

But a close review reveals that revenues never were the issue; Illinois and Chicago taxpayers contributed more than enough money to pay for pensions and school operations, had those funds been properly managed.

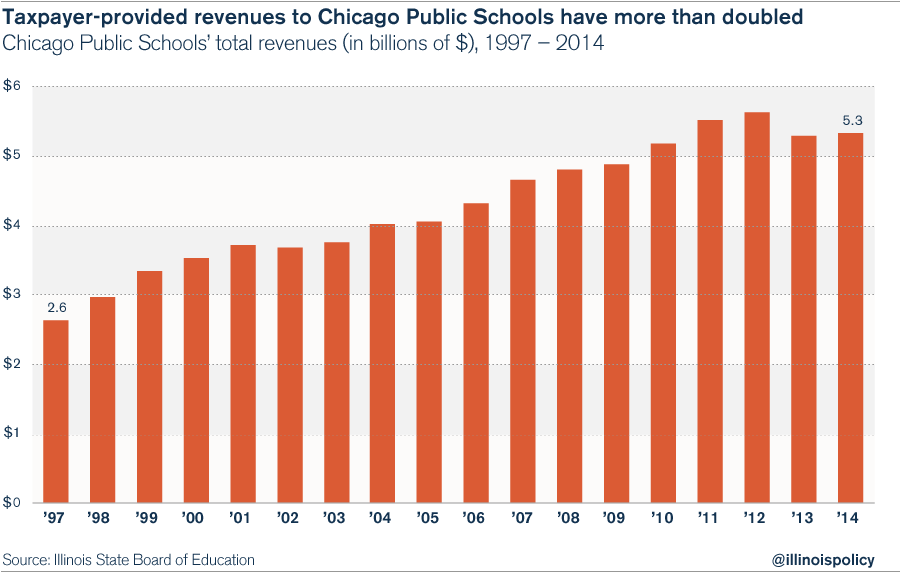

A look at the district’s finances shows CPS’ total annual revenues, including federal, state and local funds, more than doubled from 1997, to $5.3 billion in 2014.19

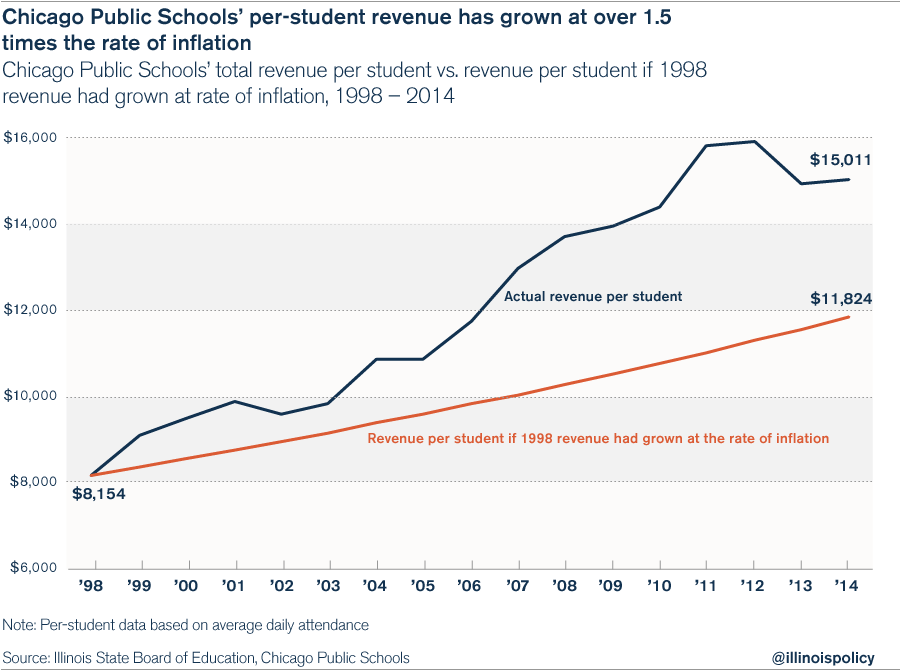

At a yearly growth rate of 4.2 percent, district revenues grew at over 1.5 times the rate of inflation during that time period.20

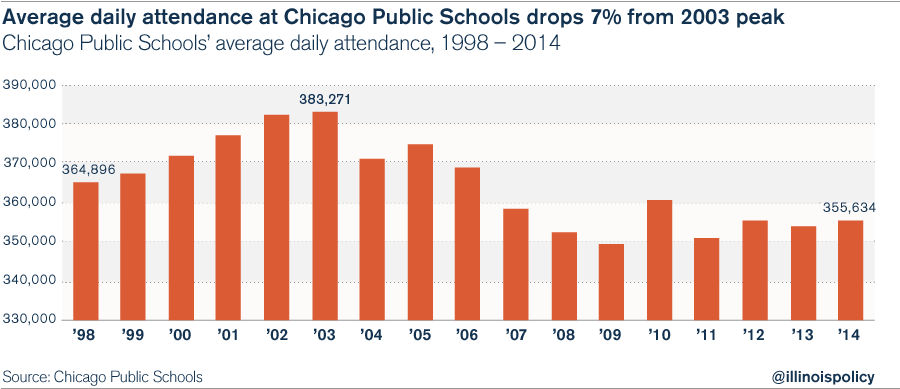

Revenue growth was even higher when measured in per-student terms. That’s because CPS average daily attendance, or ADA, has dropped 7 percent from its peak in 2003.

When adjusting for the drop in ADA, CPS revenue grew to $15,011 per student in 2014 from $8,154 in 1998 – over 1.5 times the rate of inflation.21

By comparison, had per-student revenue grown at the rate of inflation during that time period, it would have totaled just $11,824 in 2014.

Despite this significant growth in revenues, city, school and union officials continue to blame the state for not providing enough resources for the district.22

But CPS’ financial records show the state – and by extension, Illinois taxpayers – has paid its share. In fact, Springfield contributed $1.83 billion to CPS in 2014, up over 80 percent from its contribution in 1998.23

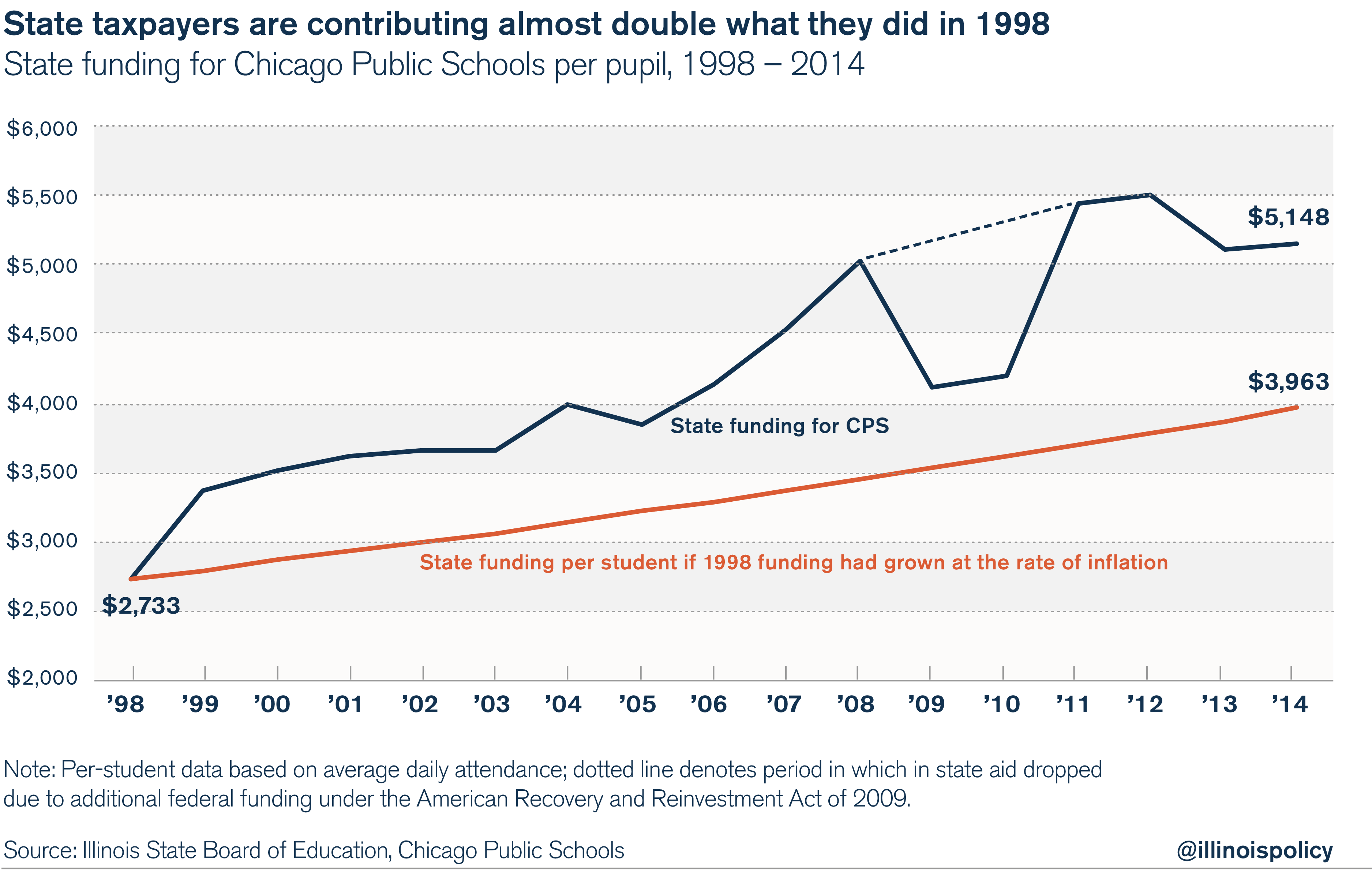

That means state funding to CPS has grown by over 1.5 times the rate of inflation since 1998. And state funding per pupil totaled $5,148 in 2014, compared with $2,733 in 1998 – an 88 percent increase.

City residents who pay property taxes have also put in their share. The portion of Chicagoans’ property-tax levy that goes directly to CPS has grown at 1.5 times the rate of inflation since 1998. The total levy for CPS reached $2.29 billion in 2014, up from $1.36 billion in 1998.24

In per-student terms, the levy has increased to $5,414 in 2014 from $3,733 in 1998.

Federal funding, the third major source of revenues, has also grown at a healthy pace. Federal funding grew to $876 million in 2014 from $415 million in 1998. That’s a compounded growth rate of 4.8 percent yearly.25

Federal revenues have more than doubled to $2,462 per student in 2014, from $1,138 per student in 1998.

CPS borrows large sums to pay current bills

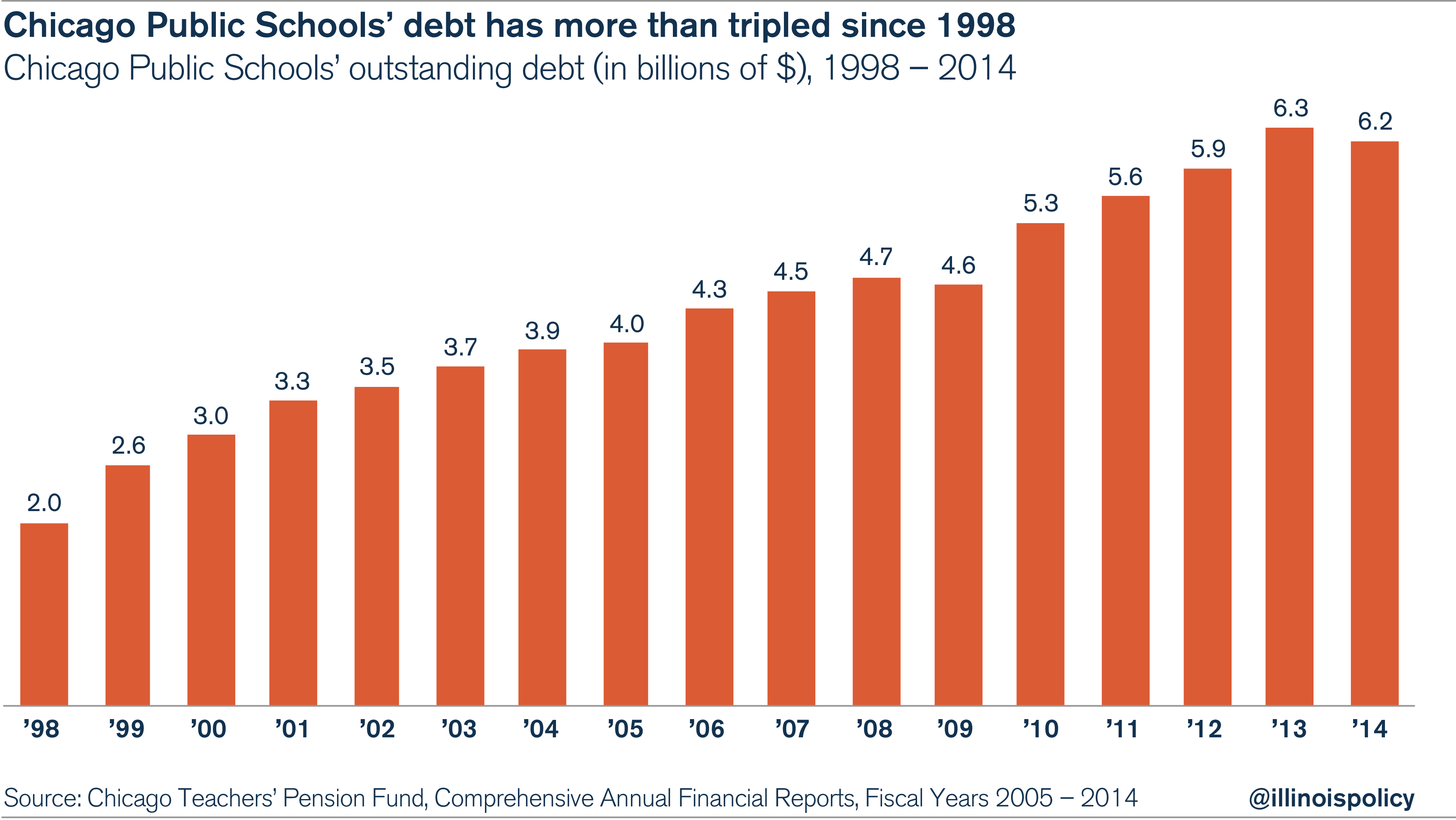

Despite having the revenue from taxpayers to pay for both pensions and operations, CPS also borrowed billions of dollars in extra funds between 1998 and 2014.

From 1998 to 2014, the district tripled its borrowings from $2 billion to $6 billion. Today, nearly 8 percent of CPS’ entire revenues are dedicated to paying its yearly debt service.26

This habit of borrowing has also contributed directly to CPS’ current crisis.

The district has issued debt to pay for unnecessary capital projects, such as renovating schools that were closed a year later. Worse yet, CPS practices “scoop and toss” borrowing – using borrowed money to push debt payments into the future – which costs the district far more in the long run.27

And despite the current cost of debt service and the fact that the district’s budget deficit exceeds $1 billion, the school board continues to borrow billions to paper over its short-term financial difficulties.

In fact, CPS borrowed the funds to make its $634 million 2015 contribution to CTPF and has authorized the borrowing of another $1.2 billion to pay for capital projects, fees on past borrowing and refinancing of older debt.28

Overall, CPS experienced significant revenue growth, above the rate of inflation, between 1998 and 2014. This growth in revenue, provided by taxpayers, should have been more than enough to pay for pensions and school operations.

Despite this, CPS still diverted funds from pensions to pay for current operations such as payroll.

3. When taxpayer money was redirected away from pensions, it went toward a growing CPS payroll, which increased pension benefits.

When the district leadership gained the General Assembly’s approval to skip required pension payments through the 1995 pension holiday, billions in taxpayer pension contributions were redirected toward CPS operational expenses.

At the time, CTU and other leaders in education formally objected to, but did not stop, the pension holiday.

The best evidence of CTU’s apparent unwillingness to defend pensions is the 2012 teachers’ strike. Instead of marching for retirement security, CTU demanded extremely expensive 30 percent raises. CTU focused its protest on pay raises despite knowing that CPS faced a $1 billion deficit the next year, and that teacher pensions were underfunded by $8 billion.29

The fact that CTU did not direct any serious protest at pension underfunding may have had to do with where the money from the pension holidays went – to CTU members.30

The funds directed away from pensions ended up being spent, most notably, on compensation. According to the Chicago Tribune:

“Diana Ferguson, the school district’s chief financial officer at the time, defended the pension holidays, saying the money saved by not paying into the pensions still went to teachers through salary increases and other benefits. ‘It’s not as if we are keeping the money from them.’”31

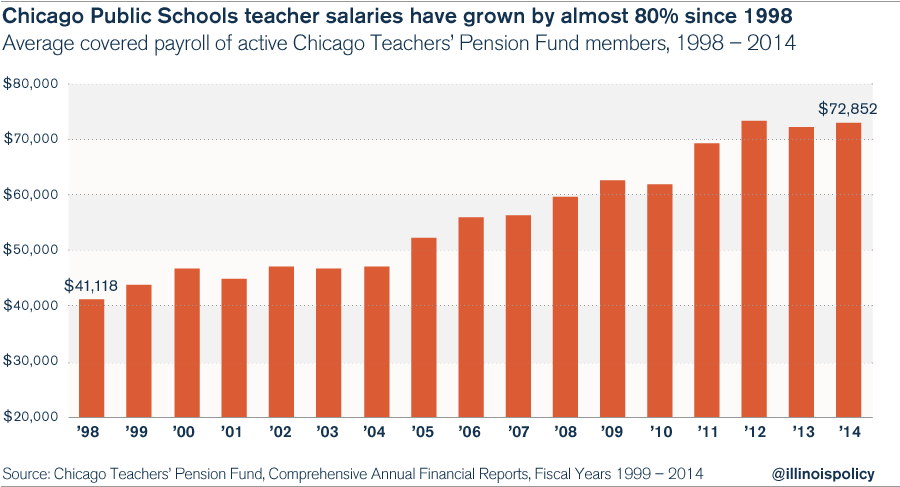

From 1998 to 2012, the district consistently handed out average annual pay increases of 4.2 percent, even though annual inflation averaged just 2.3 percent during that period.32

Overall, CPS payroll growth from 1998 to 2012 resulted in average covered payroll, or “annual average reported salaries for all active participants,” growing by 80 percent, almost twice the rate of inflation.33

In 2012 and thereafter, teacher salaries plateaued despite the fact that the most recent teachers’ contract, signed in 2012 after the CTU strike, granted teachers 16-percent pay increases through 2015. Average salary is impacted by changes in the composition of the workforce, average years worked and other demographic changes. The school closings and ensuing pink slips issued to thousands of teachers over the last several years have had a major impact on CPS’ teacher demographics.34

As a result of overall salary growth, compensation costs are taking up a larger share of CPS’ budget. In 2014, over 68 percent of CPS’ budget went toward compensation, up from 63 percent in 1998.35

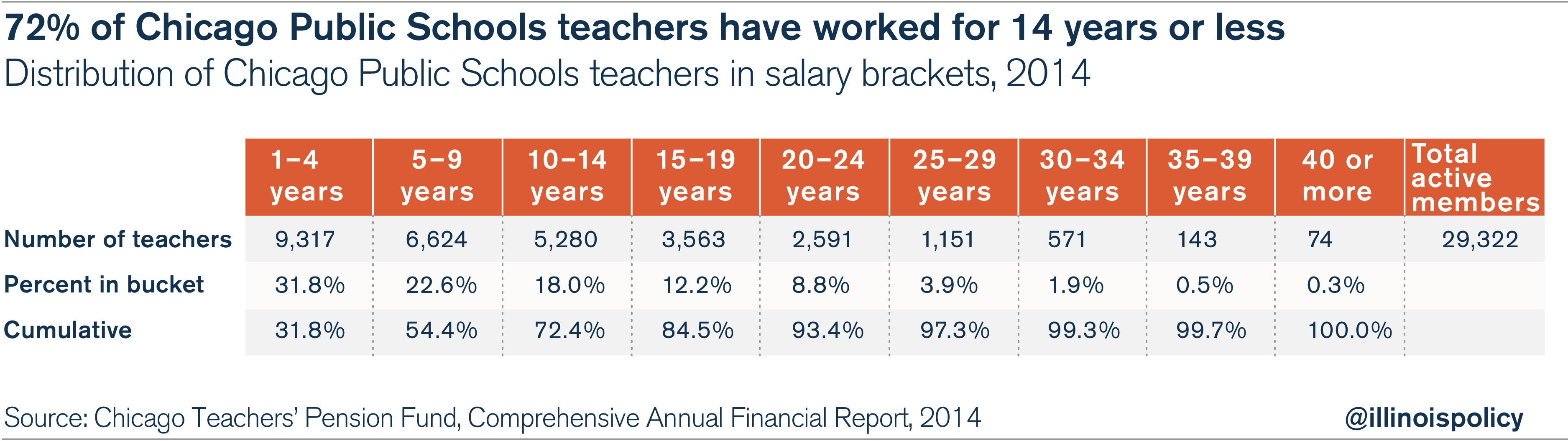

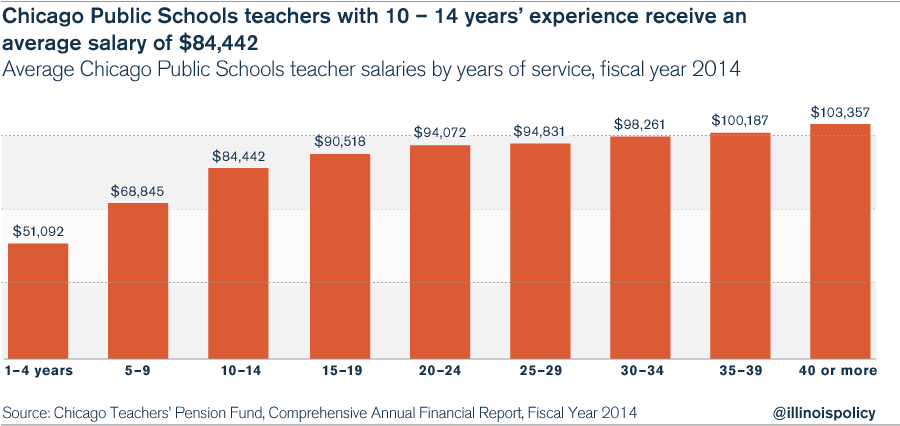

An even clearer perspective of Chicago teacher salaries comes from the CTPF annual report, which breaks down average salaries by years of service. According to the demographic data, the average salary for CPS teachers equals $73,000 because most teachers skew young. Over 72 percent of CPS teachers have worked 14 years or less.36

However, CPS’ salary schedule is designed to rapidly increase salaries during the first decade of service. With 10 to 14 years of service, a Chicago teacher’s average salary equals more than $84,000 a year.

That salary schedule has made Chicago teachers’ lifetime earnings the highest in the nation when compared to the largest U.S. school districts, according to a recent analysis by the National Council on Teacher Quality.37

This analysis also shows that CPS has the highest beginning salary for a teacher with a bachelor’s degree and ranks only a close second behind New York City in other categories.

Had CPS salaries simply grown at the same rate as median household income in Illinois over the last decade, CPS would have needed $3.2 billion dollars less for payroll expenses.38

Pension contributions did not need to be diverted toward payroll to pay teachers’ salaries. If CPS had placed the money for pensions where it belonged, teachers’ retirements would have been more secure thanks to a well-funded pension system, and teachers could still have received modest salary increases and higher levels of job security from 2004 to 2014.

Increased salaries drove pension benefits higher

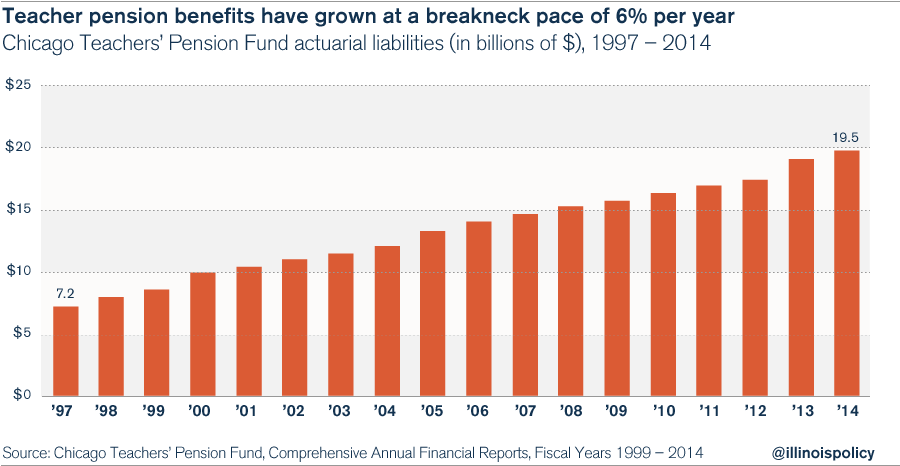

Higher teacher salaries have also contributed to a faster growth in pension benefits, putting further strain on CTPF. Because salaries determine future pensions, the pay increases helped boost benefits to an unsustainable growth rate of 6 percent over a 17-year period.39

Had benefits grown at a more modest rate of 4 percent, the pension fund’s unfunded liability would be at least $5.3 billion less than it is today.40

And those growing benefits will continue to cause pain for CTPF. As workers retire, they will put additional strain on the fund’s assets and contributions by active members.

4. Retired CTPF beneficiaries are on track to surpass the number of active workers paying into the system.

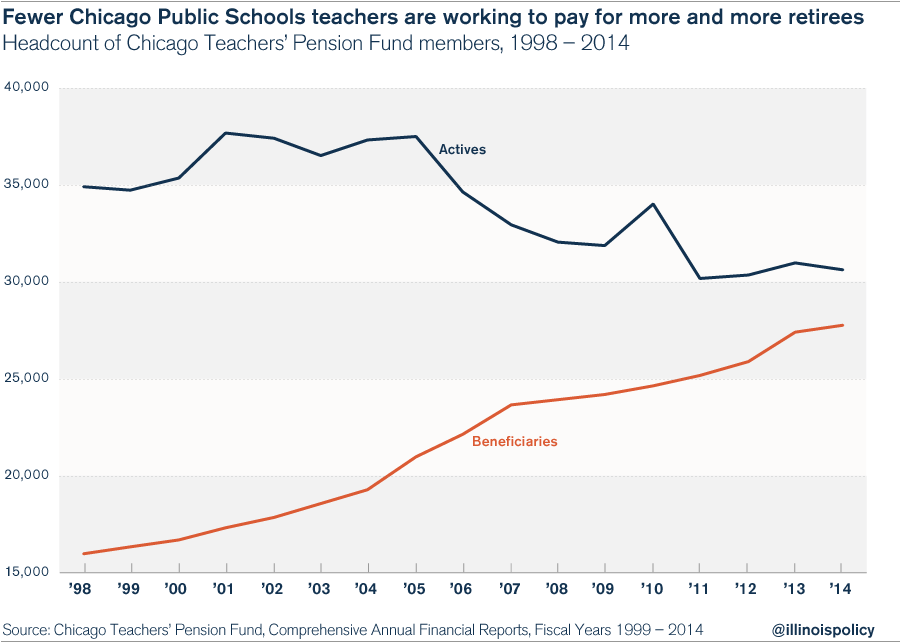

Not only does the CTPF have a massive unfunded liability, it’s also becoming actuarially upside-down in terms of membership.

The number of beneficiaries – along with their increased final salaries – continues to rise, while the number of active members paying into the fund has declined by 12 percent since 1998.41

That means more and more annuitants are drawing benefits from the pension fund compared to active workers contributing to it, pushing teachers’ pensions closer to insolvency.

Conclusion

Years of political manipulation, underfunding and a significant growth in liabilities have led to the fiscal collapse of CPS and CTPF. Despite the claims of city leaders, taxpayers and state funding deficiencies aren’t at fault.

It was district administrators, union executives and politicians who corrupted the pension system. By performing pension pickups and allowing holidays, district leaders shorted teacher retirements by more than $5 billion. And by granting unsustainably generous additional salary increases, leaders contributed to pension benefits growing far faster than average.

Legislative records show that CTU opposed the holidays, but if the union had really fought to save the retirements of its teachers, it would have been marching in the streets, doing everything it could to block the pension holidays.

Instead, the district administration gave teachers higher salaries but destroyed their job and retirement security in the process.

As a consequence, both the school district and teacher pensions are facing massive shortfalls. Now that the financial crisis has reached a critical point, the city’s and district’s leaders expect Chicagoans to foot the bill, demanding that they pay higher property and sales taxes to bail out pensions.

Essentially, city government is asking taxpayers to pay for teacher pensions twice. The first round of taxpayer contributions was diverted by politicians toward payroll and away from teacher retirements. Now taxpayers are on the hook for a second round of even larger payments to bail out the defunded retirement system.

The solution

CPS can start the long process of restoring its financial health by ending teacher-pension pickups. It’s not out of line to ask employees to pay their share of the costs associated with their own retirement benefits. That’s the standard across most industries, public and private alike. And it’s a responsible way for CPS to save at least $130 million a year.

Next, CPS should create real budget stability for itself and retirement security for teachers by terminating the CPS pension system in favor of self-managed retirement plans, or SMPs.

Some claim that the political deals of the last 20 years are the reason why pensions need a “funding guarantee” and other controls. But simply demanding a promise that throws more and more revenue at a broken pension system is not a real solution.

After all, pension systems are inherently political, opaque and void of accountability. As long as politicians maintain control over pensions, they’ll always find ways to exploit them and pass on the costs to taxpayers.

The real solution is to provide Chicago teachers and taxpayers with a funding guarantee in the form of SMPs for teachers, which would be impossible for politicians to manipulate. SMPs would also give both taxpayers and CPS more budget certainty and would grant teachers the retirement security they deserve.

And CPS won’t have to look far for a model SMP – one already exists right here in Illinois. Today, almost 20,000 active and inactive members of the State Universities Retirement System participate in a 401(k)-style plan. These state-university workers control their own retirement accounts, which aren’t part of Illinois’ own increasingly insolvent state pension systems.42

While transferring current teachers into SMPs would require a constitutional convention to change the wording of Illinois’ pension-protection clause, creating SMPs for newly hired teachers going forward is entirely within the state and city’s power.

Converting to an SMP system will help stabilize education retirement expenditures for CPS by halting the growth of CTPF unfunded liabilities for new teachers. The reform would also make future retirement expenditures easier to estimate, as the cost of SMPs would equal a steady percentage of CPS’ payroll.

With unfunded liabilities under control, CPS would no longer be subject to runaway retirement costs, allowing the district to create more stable budgets going forward.

Taxpayers shouldn’t be forced to bail out the teachers’ broken pension system with ever-higher taxes.

If CPS enacts the reforms outlined above, they won’t have to.