The problem

A common refrain sounded by public sector unions is that government workers have consistently “paid their share” into Illinois’ pension systems and the state has not.

However, the facts tell a different story.

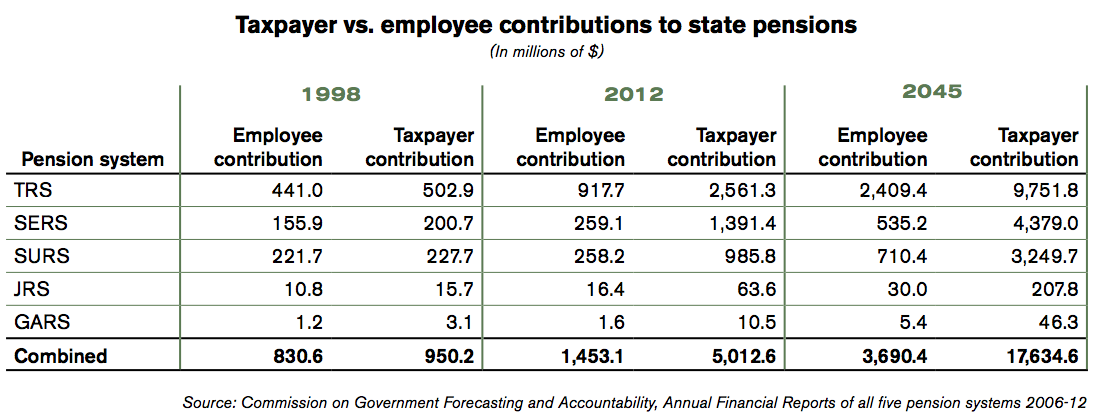

While government worker contributions to Illinois’ five pension systems have increased by 75 percent since 1998, taxpayer contributions have increased by 427 percent over the same period. In 2012 alone, Illinois taxpayers contributed $3.5 billion more to the pension systems than state workers did.

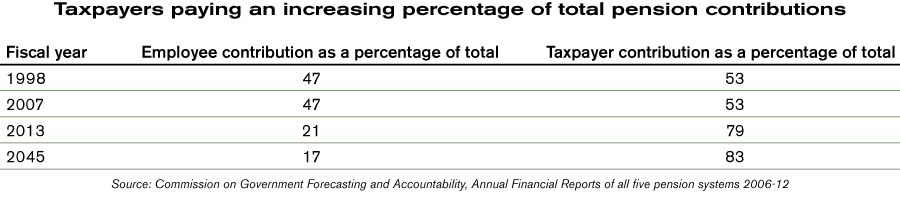

Government workers’ share, as a percentage of total contributions, has continued to decline when compared to taxpayers’ contributions. In 1998, government workers paid for 47 percent of the state’s total pension contribution; today, they only pay 21 percent. By 2045, government workers will be expected to pay only 17 percent of total pension contributions.

Taxpayers, on the other hand, will continue to pay a higher and higher percentage of total contributions. In 1998, taxpayers contributed 53 percent of total contributions. By 2045, they will be expected to pay 83 percent, or $17.6 billion out of $21.3 billion in total contributions.

The five state pension systems

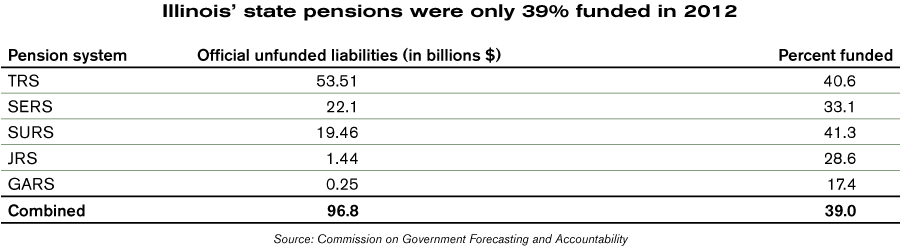

Illinois has five state pension systems, and all of them are seriously underfunded:

- The Teachers’ Retirement System, or TRS, manages pensions for teachers across Illinois (excluding Chicago).With more than 130,000 active members and nearly 95,000 retirees, TRS is the largest pension system in the state. Unfortunately, TRS also has the highest unfunded liability of the state’s pension systems. In 2012, TRS was only 40.6 percent funded and officially had more than $53.51 billion in unfunded liabilities. TRS members contribute 9.4 percent of their salary to the pension system.

- The State Employees’ Retirement System, or SERS, manages pensions for state-level employees across Illinois. It has 62,000 active members and 50,000 retirees. In 2012, SERS was only 33.1 percent funded and had officially $22.13 billion in unfunded liabilities. Under its regular pension formula, SERS members covered by Social Security contribute 4 percent of their salary, and those not covered by Social Security contribute 8 percent of their salary to the pension system.

- The State Universities Retirement System, or SURS, manages pensions for employees working at state universities. It has 71,000 active members and more than 45,500 retirees. In 2012, SURS was only 41.3 percent funded and had officially $19.46 billion in unfunded liabilities. SURS members contribute 8 percent of their salary to the pension system.

- The Judges’ Retirement System, or JRS, manages pensions for judges throughout the state. It is one of the two smaller pension systems, with only 968 active members and 725 retirees. Despite its small size, in 2012 JRS was only 28.6 percent funded and officially had $1.44 billion in unfunded liabilities. JRS members contribute 11 percent of their salary to the pension system.

- The General Assembly Retirement System, or GARS, manages pensions for members of the Illinois General Assembly. Despite having only 176 active members and 294 retirees, GARS has the dubious honor of being the worst-funded pension system in the state. In 2012, GARS was only 17.4 percent funded and officially had $251 million in unfunded liabilities. GARS members contribute 11.5 percent of their salary to the pension system.

Combined, the five state pension systems were only 39 percent funded in 2012 and had an official unfunded liability of $97 billion dollars according to the Commission on Government Forecasting and Accountability.

However, that underestimates the state’s unfunded pension liability. Illinois’ pension funds use overly optimistic assumptions in calculating their unfunded liability, including an expected 8 percent yearly investment return.

To calculate a more realistic unfunded liability, Moody’s Investors Service reported Illinois’ current shortfall using a new methodology.

Under the methodology, which uses more reasonable investment assumptions, Illinois’ 2011 unfunded liability jumped 65 percent to $133 billion.

For 2012, the Illinois Policy Institute – using Moody’s methodology – estimated that Illinois’ pension systems were approximately 23 percent funded, and the shortfall exceeded $200 billion.

Under defined benefit systems, taxpayers pay increasingly larger contributions

Under Illinois pension law, each pension system is required to reach 90 percent funding by 2045.

For this to happen, taxpayers will have to pay greater and greater contribution costs going forward to pay for both the systems’ normal cost and its current unfunded liabilities.

To reach 90 percent funding, taxpayers will be forced to contribute at least $385 billion to the pension systems over the next 30 years. That’s nearly $81,000 per household and more than four times what state workers are expected to contribute.

And that $385 billion won’t be paid off in equal installments. Instead, Illinois law requires contributions to undergo a payment ramp, wherein taxpayers will see their annual contribution to pensions increase every year.

In 2012, taxpayers contributed $5 billion to the pension systems. In 2014, they are expected to contribute $6.8 billion. By 2045, they are expected to contribute $17.6 billion, or about $3,600 for every household in Illinois.

But these numbers are actually a low estimate of how much taxpayers will end up contributing.

The state’s current funding requirement assumes the unfunded liabilities of the pension systems will not increase further. But the unpredictable nature of defined benefit programs and the last two decades of actual pension history tell us they will continue to increase.

Taxpayers are not only responsible for paying off the system’s current unfunded liabilities; they are also responsible for all future increases in liabilities as well.

Government workers, on the other hand, continue to pay a constant percentage of their payroll to the pension system. Their total contribution to the pension system only increases when their salaries increase or more workers are hired. They are not required to pay more into the pension system, regardless of increasing shortfalls and growing liabilities.

Taxpayers are paying for the failures of defined benefit plans

Taxpayers are seeing their contributions rise dramatically because the pension system continues to rely on defined benefit plans. Defined benefit plans are rife with complexities and full of surprises that increase costs year after year. That’s why, no matter how much money taxpayers and retirees contribute into the pension system, the underfunding always gets worse.

The proof is in the pension systems’ past performance. According to the Commission on Government Forecasting and Accountability, the state’s pension shortfall grew by $76 billion from 1996 to 2012. Of that amount, nearly $45 billion came from some form of missed “expectation”:

- The investment returns for the state’s five pension funds were lower than their assumed 8 percent expectation. Cost to taxpayers: $17.2 billion.

- Unplanned benefit increases for employees. Cost to taxpayers: $5.8 billion.

- Changes in actuarial assumptions. Cost to taxpayers: $8.8 billion.

- “Other” actuarial factors. Cost to taxpayers: $12.9 billion.

Breaking down the taxpayer and employee contributions into the individual pension funds tells a similar story. Taxpayers are on the hook for increasing costs in every single pension system.

What follows is a look into how much taxpayers’ contributions will grow for each individual fund.