Kids Win. Taxpayers Win.

By Collin Hitt

Kids Win. Taxpayers Win.

By Collin Hitt

Tens of thousands of Chicago families are trapped in failing public schools. A new school voucher program has been proposed by the Reverend Senator James Meeks. Its goal is to give parents of students enrolled in the worst performing public schools the choice to send their children to private schools.

Similar programs in other states have been shown to improve academic outcomes for the students who use vouchers, and surveys unsurprisingly show that parents are happier with their new schools. Moreover, when the impact of school voucher programs on public school performance has been researched, practically every study has shown that the increased competition for students has actually led surrounding public schools to improve as well.

As a means of improving education in inner-city Chicago, Rev. Meeks’ proposal is solid. Many lawmakers, however, have raised concerns over whether state government can afford to pay for students to attend private school. This policy brief examines that question, and finds that the school voucher program proposed by Rev. Meeks will almost certainly lead to significant savings for state government.

A school voucher program requires the state to cut new checks as students transfer to private schools from failing public schools. However, this also means that the state will lower the amount of its regular payments to Chicago Public Schools (CPS), since the district would see a corresponding decline in enrollment. How do these two factors balance out? In the scenario we find most likely, with twenty thousand students redeeming school vouchers at an average of $4,500 apiece, the savings from reduced General State Aid (GSA) payments would not only cover the cost of the school vouchers but also lead to a five-year surplus of $37 million.

Calculating the Fiscal Impact of School Vouchers

A pilot school voucher program can lead to significant savings for state taxpayers. Any drop in public school enrollment – such as that created by a school voucher program – would lower the state’s financial obligation to the district. Local revenue streams, which account for roughly half of CPS’s budget, would be unaffected. In calculating the potential savings to state government, this paper looks only at how the state’s General State Aid obligation would be affected by various potential declines in enrollment.

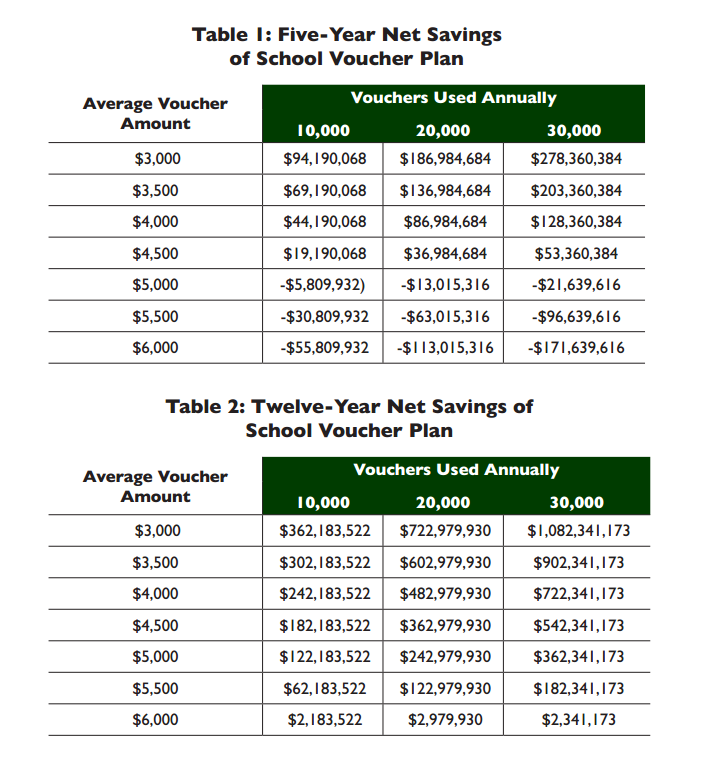

Tables 1 and 2 present the findings from our analysis, according to the wide range of possible scenarios.

Enrollment Declines and General State Aid

General State Aid is the primary – though certainly not the only – means through which state government subsidizes public education in Chicago. CPS receives approximately $1.2 billion in General State Aid support. There are also grant programs for transportation reimbursement, bilingual education, reading improvement and special education that together provide hundreds of millions of dollars in support to CPS. General State Aid, more than these other programs, is influenced by enrollments. All other factors aside, the more students a district has, the larger its state aid payment. As such, this policy brief focuses solely upon General State Aid, as it relates to potential voucher outlays.

The “General State Aid Overview” published by the Illinois State Board of Education contains a lengthy explanation of how a given school district’s General State Aid entitlement is calculated. Four main variables influence a given district’s state aid entitlement:

- The Foundation Level, as determined annually by the Illinois General Assembly, currently at $6,119;

- Average daily attendance within the district for the past three years;

- Average “Low Income” student enrollment within the district for the past three years; and

- Total assessed property value within the district, which provides the base for local property taxes.

Local property taxes are the initial revenue stream for public schools. If a district is deemed to have a high property tax base relative to the number of its students, then it receives less state aid – with the expectation being that the district will draw upon local resources to fund local schools.

However, if a district has a relatively low property tax base relative to its number of students, then it receives state aid sufficient to fund each student’s education at the statutory Foundation Level, currently set at $6,119. Moreover, the higher a given district’s concentration of low income students, the more state aid it is entitled to receive on a per pupil basis via the GSA “Poverty Grant.”

In short, each district has a predefined amount of per pupil resources that it should have access to, according to state law. In a vast majority of instances, local resources are insufficient to cover the state-set levels of per pupil spending. General State Aid covers the difference.

A school voucher program would have an impact on two of the main variables of Chicago’s General State Aid application, since the program would create a slight decline in enrollment. A district’s average daily attendance (ADA) would drop, as would the total number of Low Income students.

This will affect the Chicago Public School’s General State Aid application in two ways. For one, it lowers the amount of students for whom the district and the state will need to support financially. Second, it will mean that an unchanged level of local property tax resources will be available for a reduced number of public school students, thus meaning that fewer state resources are needed to aid Chicago schools in reaching Foundation Level funding. Both of these factors would lower the state’s General State Aid payment to CPS.

Gross Savings to State Aid

For the purposes of this paper, we assume that students who use school vouchers attend school at a similar rate as their peers and have similar economic backgrounds. This is to say – for the purpose of our projections – a potential five percent drop in CPS enrollment would lead to an identical five percent drop in both average daily attendance and low-income student enrollments. For the purposes of our projection of General State Aid obligations, we assume that all other relevant factors will remain constant at 2008-09 Levels.

Projected state aid obligations to CPS will total $6.11 billion between the five-year period of FY2012 to FY2016, averaging $1.22 billion per year. A ten thousand student drop in annual enrollment would lower that obligation to $5.86 billion, showing a gross savings of $244 million. Twenty thousand and thirty thousand student decreases would lower state aid obligations by $487 million and $728 million, respectively, over that five-year period.

It is worth noting that the current formula for General State Aid reimburses districts for three-year averages in enrollments. This means that, even though a school voucher program would lead to an immediate decrease in district enrollment, state aid payments would take three years to fully reflect that decrease. As Table 2 shows, we find that the state will eventually realize a net annual savings as a result of a school voucher program, regardless of the popularity of the program or the average that vouchers are redeemed for.

Potential School Voucher Outlays

The pilot school voucher program, as outlined in Senate Bill 2494, would give parents with children attending the bottom-performing ten percent of public schools “a School Choice Voucher for payment of qualified education expenses incurred on behalf of the qualifying pupil at any participating nonpublic school in which the qualifying pupil is enrolled.” The voucher can be redeemed for as much as the current state Foundation Level of $6,119. This is more than sufficient to cover the average cost of private elementary school tuition in Chicago.

It is impossible to know beforehand what exactly will be the average value of the school vouchers issued. Similarly, it is impossible to predict exactly how many students will take advantage of the program. Thus we have created Table 3 to demonstrate the various potential outlays for school vouchers, according to various assumptions about voucher program enrollments and average voucher amount.

The math is uncomplicated: if 20,000 vouchers are redeemed at an average amount of $4,500, then the total annual voucher outlay would be $90 million, which is roughly equivalent to 7.5 percent of what the state pays annually to the district in General State Aid. What we show in full in the Appendices is that concomitant reductions in General State Aid – reflecting the marginal decline in enrollment for the district – will more than cover the costs of the voucher program.

In every scenario, a school voucher program will generate annual net savings to state government by its third year.

In only a few instances – if voucher enrollment is very high and the average voucher amount approaches the Foundation Level of $6,119 – will it take longer than six years for the state to realize a net savings. In these instances, it will take between seven and twelve years for state government to realize a net savings from the voucher program. This is not due to any inherent cost of a voucher program per se. Rather; Illinois’s current state aid formula takes three years to fully adjust to permanent enrollment decreases. In effect – because General State Aid is paid out based on three-year enrollment averages – the state will temporarily and heavily compensate CPS for the thousands of students who have already accepted a voucher and left the public schools.

This slow adjustment will soften the financial impact to the district, to be sure, though it will also delay the date by which a school voucher program will generate savings for state government. Under our projections, there are no instances wherein Rev. Senator Meeks’ proposed school voucher program would come at a net cost to state taxpayers.

Conclusion

As the Rev. Senator Meeks said to the editorial board at the Chicago Tribune, “the worst thing that could happen is that a child might get a decent education,” if the state creates a school voucher program. And indeed, research on existing voucher programs suggests that Chicago students who use vouchers will end up in safer schools that can give them a better education, while surrounding public schools will in turn improve their performance as well.

Moreover, as shown above, the pilot school voucher program outlined in Senate Bill 2494 would likely generate significant savings to state government simply by reducing its General State Aid liabilities. This says nothing of the potential savings to other educational grant programs, some of which can be adjusted to reflect declining enrollments. Those savings could be further invested in public education or used to pay down portions of the state’s record budget deficit. In either case, as the editorial board of the Tribune rightly anticipated, “the Meeks plan wouldn’t cost the state a dime.”