Power outage: Inside Illinois’ Hispanic opportunity gap

By Austin Berg

Power outage: Inside Illinois’ Hispanic opportunity gap

By Austin Berg

2 sides, 1 coin

“He says he wants to go to [Cristo Rey] St. Martin because the boys who go there get good jobs,” says Deborah Valderas of her 9-year-old son, Daniel.

Cristo Rey St. Martin College Prep is the only private school that serves high schoolers in Waukegan, Illinois, a northern Chicago suburb home to some of the lowest-performing public schools in the state.

Daniel is a fourth-grader at Most Blessed Trinity Academy, a private elementary school in the city of 90,000. Deborah pays for his education through her earnings as a hotel maid. She makes $8.67 an hour.

“I get my tax return, put it aside for his tuition, pay my bills and make up the rest selling flan,” she says.

“I was born poor and I will die poor. The best inheritance I can give to my children is an education.”

Deborah’s son dreams of finding a good job – the kind that used to come from people like Gerry Witter, owner of Waukegan’s Electrical Contacts Plus, a high-tech manufacturer producing electrical relays used in cars that has severely downsized its production in the U.S over the last few years.

Back in 2005, when Gerry began hiring in Waukegan, he noticed something strange. Workers coming into his shop were struggling with automated equipment, so he developed a 10-question math test for everyone who applied for a job. The results were extreme.

“A few people at the very top, many people at the very bottom and no one in between,” he says.

“That’s when I knew something was wrong with the school system. Many of these people lacked [basic] skills, and companies can’t afford to teach those skills.”

He went searching for answers.

“I went down to the unemployment office and asked, ‘How many skilled people do you have?’ They said ‘Hardly any, most of the people that come in can’t even fill out the forms.’”

That’s when Gerry decided to take matters into his own hands.

He now runs a tutoring program teaching basic math to 15 of Waukegan’s fourth and fifth graders every Monday using Khan Academy, an online learning platform. As their children receive tutoring, Waukegan mothers attend classes on family health.

“The kids are smart, but they need motivation to think they’re smart. It’s not just a problem of them learning. It’s a problem of believing in themselves,” Gerry says.

“They need unique teaching methods that the schools aren’t giving them. I want the schools here to start using those methods.”

Gerry isn’t the only one who wants to see the school district improve and innovate. Nearly 70 percent of Waukegan respondents to a We Ask America poll gave their schools a grade of C or below. And 2 out of every 3 Waukeganites reached in canvassing efforts supported school choice.

But little has changed.

State of the state

New research from the Illinois Policy Institute shows largely Hispanic communities such as Waukegan, which is home to a 75 percent Hispanic student population, are struggling to provide quality schooling. Across the state, the educational outcomes of a booming Hispanic student body are far worse than that of their white peers.

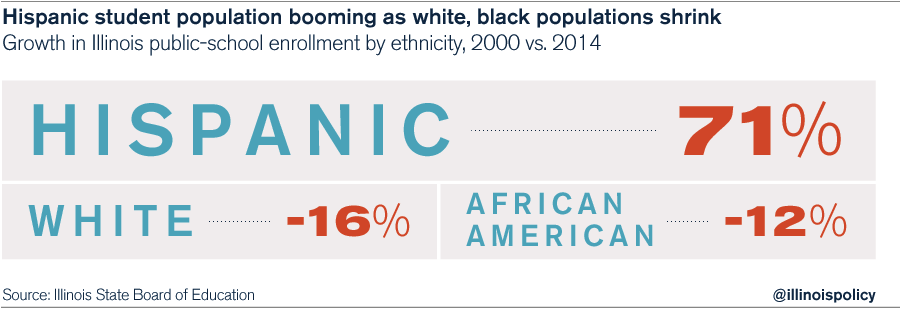

While the state’s black and white student populations have shrunk by 16 percent and 12 percent, respectively, since 2000, the Hispanic population has grown by more than 70 percent. But their needs are not being met.

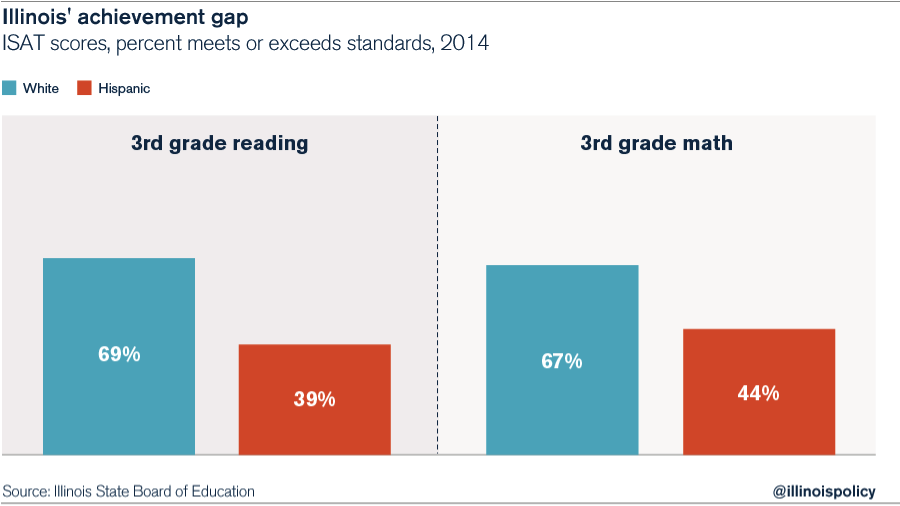

Learning gaps start early. If children can’t read at grade level by the third grade, the likelihood they’ll drop out by high school rises dramatically. In Illinois, fewer than 4 in 10 Hispanic third-graders can distinguish between the main idea and the supporting details of a story – the third-grade reading standard established in the Illinois Standardized Achievement Test, or ISAT. But nearly 7 in 10 white third-graders in Illinois can do this.

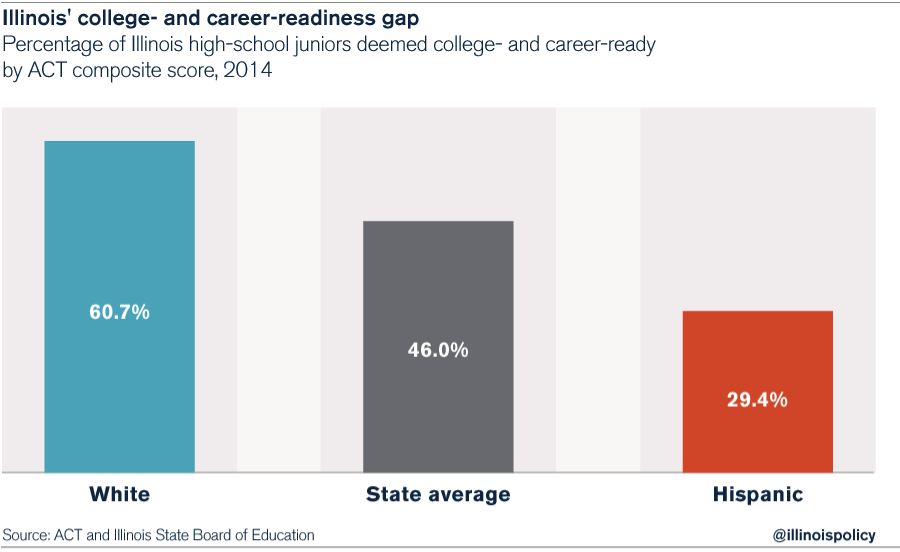

That gap persists into later grades, as revealed in ACT test results from high-school juniors across the state. Fewer than 30 percent of Illinois’ Hispanic high-school juniors earn a composite score of 21 or higher – indicating college- and career-readiness – compared with a state average of 46 percent and a white average of over 60 percent.

Lack of a quality education put minority workers at a huge disadvantage during the last recession. The employment rate for Latino men in Illinois dropped by more than double the rate of all workers ages 25-54 from 2006-2013, according to data from the Illinois Department of Employment Security.

Blame for the opportunity gap falls indiscriminately on parents, students and circumstance. Children are scolded for poor effort or deficient language skills; parents for lack of preparedness and engagement. Many blame poverty.

But some Waukegan parents say the problem isn’t poverty; it’s power.

Imbalance

“Just because someone lives in a certain place doesn’t mean they don’t deserve access to a quality education,” says Diana Baerga, a single mother in Waukegan. Her 8-year-old son Ian has autism. Her frustration with the school district is evident.

“We as parents are seen as troublemakers, as a nuisance. If we bring up concerns we are brushed aside,” she says. “When you say something they make you feel like a diva.”

After years of struggling with administrators at local public schools, Diana finally entered her son in a lottery for a spot in a brand-new charter school in Waukegan for the upcoming school year. But Ian’s name wasn’t picked. He sits at No. 30 on the waiting list.

“My first reaction was that we weren’t good enough,” says Diana. “That’s when I learned the difference between charter and choice. School choice puts the ball back in the parents’ court.”

Diana is far from the only parent looking for a way out. One look at the state of Waukegan schools and anyone can see why. In the city’s lowest-performing elementary school, Carman-Buckner, only 2 in 10 third-graders can read at grade level.

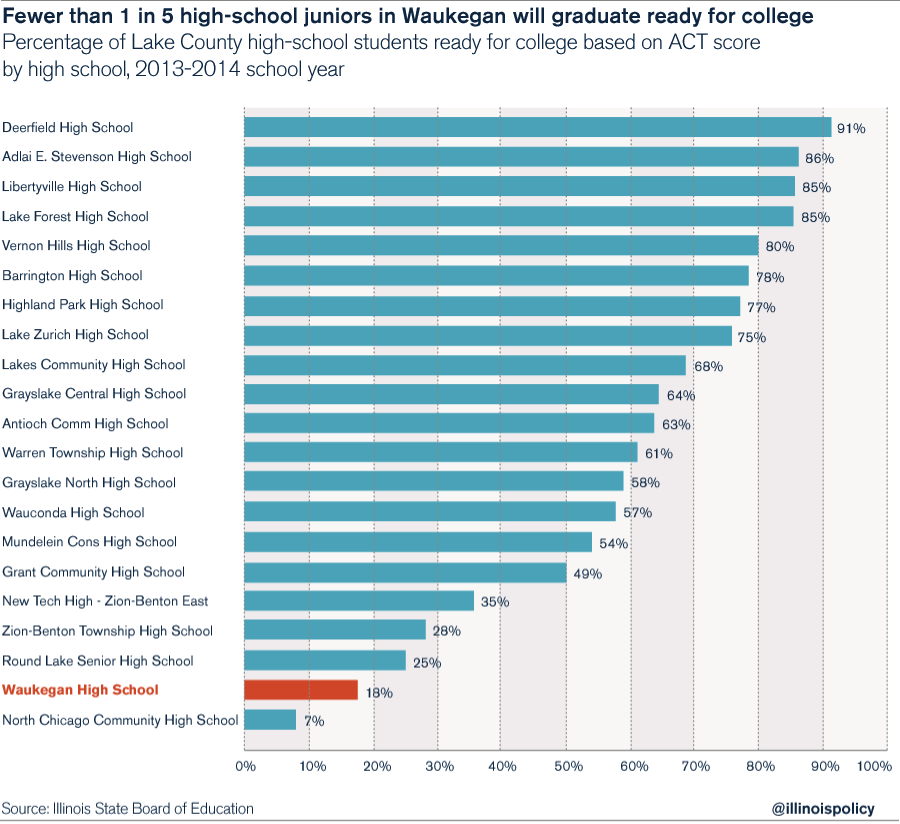

As is the case statewide, these results come with severe consequences later in life. Children are put at an enormous disadvantage in later grades, as is evident when comparing Waukegan High School to other high schools in Lake County, home of some of the most affluent communities – and best-performing school districts – in the state.

Diana has made her preferences clear. “I would like to see more structure in our schools. More structure and more accountability,” she says.

Many Waukegan parents share her demands. But only a select few are able to act on them.

Escape hatch

Deborah’s son Daniel wasn’t wrong about Cristo Rey St. Martin leading to better job prospects.

Baltazar Pizano Sr., a Waukegan father of four, may know this better than anyone. Each of his children has graduated or is currently attending Cristo Rey, where 100 percent of graduates from the class of 2015 will attend college (more than 80 percent will attend a four-year college) and an overwhelming majority of students are Hispanic. Cristo Rey students are enrolled in a rigorous work-study program, which helps pay off part of their tuition. Almost every student receives additional financial assistance from the school.

Baltazar Sr.’s eldest daughter, Mariana, graduated from Loyola University Chicago and now works at an Illinois law firm. Baltazar Jr. graduated from Loyola’s business honors program in 2015 and begins work at Ernst & Young as an accountant in the fall. Eloy is studying at the Milwaukee School of Engineering. Baltazar’s youngest son, Jose, is enrolled at Cristo Rey.

Baltazar Sr. left Guanajuato, Mexico, nearly 20 years ago for Waukegan, and became a U.S. citizen to provide better opportunities for his children. But upon arrival, he was caught off guard. “Down the street on the corner there were kids selling drugs every day and no one ever did anything about it,” he says.

“That’s when I decided I needed to put my kids in a private school. They needed structure and discipline.”

Cristo Rey’s work-study model and sky-high expectations have allowed students like Mariana, Baltazar Jr., Eloy and Jose to access opportunities their father never could have imagined in Guanajuato.

And among those who have left Waukegan for college campuses full of students from more privileged backgrounds, hope in the city remains strong. Young, educated Waukeganites know the city is struggling and want to be part of the solution.

“A lot of my friends who graduated plan to come back and do something for the community,” says Baltazar Jr.

“[Waukegan] is not in good shape, and when you leave, that’s brain drain. People are cognizant of that. You realize you can have some positive influence if you come back.

“Our parents gave up a lot to put us through school. So it’s your responsibility to give back,” he says.

Meek to mighty

Community revival takes a combination of flourishing schools and employers eager to hire skilled labor. Waukegan and many other Illinois communities have neither. This creates a vicious cycle.

Hoards of students are graduating high school without basic skills, rendering them unhirable. Those fortunate enough to beat the system and attend college are forced to take work elsewhere. And the odds of winning outside investment to spur development are slim to none without a skilled workforce.

But one tool to begin chipping away at this problem – more school choice – has been deployed less than 10 miles north of Waukegan in Wisconsin. In 2013, the Badger State enacted a statewide voucher program where low-income parents are given state money to send their children to a school of their choosing. Milwaukee, Wisconsin, a one-hour drive from Waukegan, is home to the largest and oldest local school-choice program in the nation. More than 25,000 Milwaukee students use vouchers to attend a school of their choosing.

Like governments in New Orleans, Nevada and North Carolina, political leaders in Wisconsin have empowered parents to make the best educational choices for their children. Tying public dollars to parent demands can open the door for growth in options and opportunities, forging a future where the unique needs of every child are met. Deborah’s son, a shy kid dreaming of a steady career, can attend a smaller school focused on math and science. Diana’s son, who needs specialized services to set him up for a life of independence, can attend a school focused on children with special needs.

In Waukegan and across the state, rebirth requires rethinking the status quo.

“Everything happens for a reason, and when you feel defeated something better comes along … a better tomorrow is looking like choice to me,” says Diana.

Will those in power grant that choice?

Illinois families are waiting for the answer.