The debt never paid: Re-entry reforms for Illinois

By Bryant Jackson-Green, David Camic

Download Report

The debt never paid: Re-entry reforms for Illinois

By Bryant Jackson-Green, David Camic

Download Report

Illinois’ criminal-justice system should hold offenders accountable for their crimes. This happens through a loss of freedom during a prison sentence, probation and mandatory supervised release. But the criminal-justice system must also focus on helping offenders become self-sufficient, productive community members, so they do not continue to cycle in and out of the corrections system. The Illinois Constitution states, “All penalties shall be determined both according to the seriousness of the offense and with the objective of restoring the offender to useful citizenship.”1 When someone commits a crime, he or she should expect to suffer the consequences. But that person should also be expected to find employment, support his or her family, and become a responsible taxpayer after paying his or her debt to society.

Right now, public policy undermines this goal. In fact, Illinois’ criminal-justice system continues to punish former offenders well after they’ve served their sentences – making them struggle to find work, reliant on welfare, and unable to build stable futures for their families. Former offenders face barriers in the form of occupational-licensing restrictions, loss of work skills during incarceration, and concerns of employers who may be reluctant to hire anyone with a criminal record – even when an ex-offender has reformed and would be a good fit for the job.

The state’s system punishes people like Lisa Creason, a mother of three, who made mistakes earlier in life, but turned things around. Over 20 years ago, at the age of 19, Creason tried to steal money from a Subway cash register so she could feed her daughter. At 20, she was sentenced to prison for three years for robbery, along with an unrelated burglary charge. But she resolved to make changes. Creason started a nonprofit to fight youth violence in Decatur, Ill. She later went back to school and completed a nursing degree while raising her children and working as a certified nursing assistant, or CNA. Her goal was to become a registered nurse, which would allow her to advance in a career she loved, and afford a better life for her children.

But in 2011, Illinois lawmakers updated the Health Care Worker Background Check Act to prohibit anyone convicted of a “forcible felony” such as robbery from being licensed as a health care worker.2 Although she had earlier obtained employment as a CNA and proved she could be trusted to work with patients, Illinois state law prevents Creason from working as a registered nurse, the more highly compensated profession for which she earned her degree. As a result of the policy change, Creason and her children remain on government assistance – with economic success just out of reach.3

Creason’s story is just one example among many of former offenders working to overcome their criminal records. Over 30,000 people leave Illinois prisons each year, according to the Illinois Sentencing Policy Advisory Council, or SPAC.4 And as of 2011, 65 million adults, or nearly 21 percent of the country at the time, had some kind of criminal record.5

What holds these people back are the collateral consequences of a criminal record – civil penalties imposed by statute, administrative rules or courts that result from a criminal conviction.6 Collateral consequences include legal bars to employment, generally for fields that require government to issue licenses; bans on some public and private housing; and prohibitions against receiving federal loans for higher education, as well as other public benefits. On the state level, anyone with a felony drug conviction is ineligible to ever work for a park district or school, or in many medical occupations.7 These restrictions are imposed by law and compound the effects of private employers’ wariness about hiring persons with criminal records.

A criminal record also poses an immense challenge because it reduces the likelihood that a private employer will hire an ex-offender. One overview by the Center for Economic and Policy Research suggests that criminal records have “[cost] the United States about 0.4 to 0.5 percentage points of GDP in 2008, or roughly $57 to $65 billion” in economic output as a result of lower employment.8 Other studies have highlighted how criminal records magnify disparate outcomes for minorities in hiring processes. For example, one Northwestern University study showed that 17 percent of white ex-offenders were contacted for interviews after applying for jobs, while a mere 5 percent of black ex-offenders received post-application invitations to interview. These rates for ex-offenders compared with an interview-invitation rate of 34 percent for whites without criminal records and a rate of 14 percent for blacks without criminal records.9 Policymakers must keep in mind the disparate racial impact of a criminal record given that almost 60 percent of Illinois’ prison population is black, and black Illinoisans are already more likely to experience unemployment.10,11

Concerns about the stigma inherent in a criminal record led policymakers in 19 states, including Illinois, and over 100 cities throughout the country to implement “ban the box” policies, which prohibit employers from inquiring about a job applicant’s criminal history, at least until after an interview or a job offer has been made. While these efforts were well-intentioned, they’re imperfect in several respects. Employers now conduct a background check after interviewing a candidate instead of asking about criminal history on the application. This might help employers to make more informed hiring decisions, but it may also lead them simply to reject prospects later in the application process.12 Business owners have also voiced concern about the compliance obligations imposed by “ban the box,” which add hiring-related financial and time costs that smaller businesses in particular may find extremely burdensome.13

Illinois needs policy solutions to the real problems former offenders face in finding employment, but reformers too often rely on the threat of lawsuits to force private employers to hire more ex-offenders.14 Business owners and hiring managers have legitimate concerns about the risks involved in hiring former offenders – from discrimination lawsuits to the perception that an employee with a record is more likely to commit a new offense in the future. Instead of punishing businesses for their due-diligence concerns, reforms should focus on relieving government-imposed barriers, limiting lawsuit liability for employers, and enabling nonviolent offenders to better position themselves for success in the job market.

This report discusses some of the barriers to employment former offenders face, and outlines policy changes to address them. As solutions, the Institute proposes reforms in three areas to facilitate more employment among former offenders:

1. Sealing expansion: Allow most nonviolent offenders the chance to apply to have their criminal records sealed as soon as they successfully complete their prison sentences or parole, if applicable.

2. Business-liability reform: Protect businesses from lawsuits based solely on hiring employees with criminal records.

3. Occupational-licensing reform: Remove legal barriers that prevent former offenders from working in most licensed occupations.

The economic case for re-entry reform

Illinois has a costly prison problem. The state spends $1.4 billion a year on prisons, or over $21,000 just to hold an inmate. Costs increased as the prison population exploded by over 300 percent between 1978 and 2013, leading Illinois to have the most overcrowded prison system in the U.S. by the end of 2014.15

Unfortunately, the state spends many of its corrections dollars on people who’ve already gone through the system. In Illinois, over 45 percent of offenders released from prison each year will have returned three years later – at a terrible social and financial cost.

Certainly, one of the strongest cases for removing barriers to work for ex-offenders is that the alternative – unemployment, underemployment or a return to crime – is immensely costly for former offenders and taxpayers alike.

One reason these barriers are so expensive is that without work, former offenders are likely to resort to crime to make ends meet, perpetuating a cycle of recidivism.

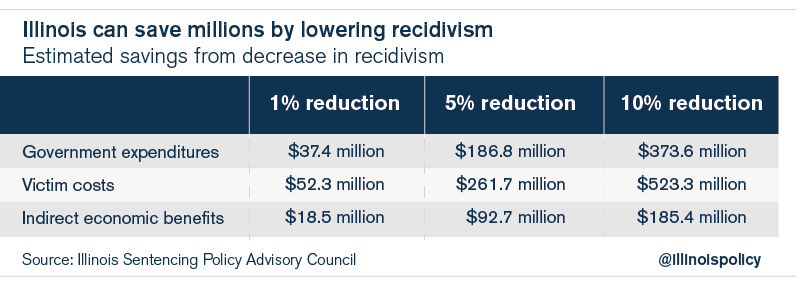

Each instance of recidivism in Illinois costs the state, on average, approximately $118,746, according to a report by SPAC.16 The report breaks down this average cost into three parts: Taxpayers cover $40,987 by paying for arrests, trials, court proceedings, incarceration and supervision; $57,418 of the cost is borne by victims who have been deprived of property, incurred medical expenses, lost wages, and endured pain and suffering; and another $20,432 comes from indirect costs in foregone economic activity.

Assuming Illinois’ recidivism rate stays the same, taxpayers themselves will pay approximately $5.7 billion for recidivism costs over the next five years, to say nothing of the burdens borne by crime victims.

But even small reductions in recidivism can lead to substantial financial savings for taxpayers and victims, as well as increased economic activity.

If re-entry policy changes reduced recidivism by just 1 percent, Illinois would save $37.4 million in prison, court and policing costs. If it fell by 5 percent, these savings would jump to nearly $187 million, along with $93 million in avoided economic losses and $262 million in victimization costs not incurred.17 Given that repeat offenses cost taxpayers and crime victims so much, and the considerable savings that could result from effective strategies to reduce them, policymakers and voters should welcome new policies that discourage crime by encouraging productive employment.

Just as important as financial costs, however, are the social costs of not prioritizing rehabilitation and employment in the state’s criminal-justice system. Around 70,000 children in Illinois have a parent behind bars at any given time,18 which means that hundreds of thousands have parents with felony records. This is a problem, because the children of incarcerated parents are substantially more likely to experience economic hardship, and in many cases end up involved in the criminal-justice system themselves.19

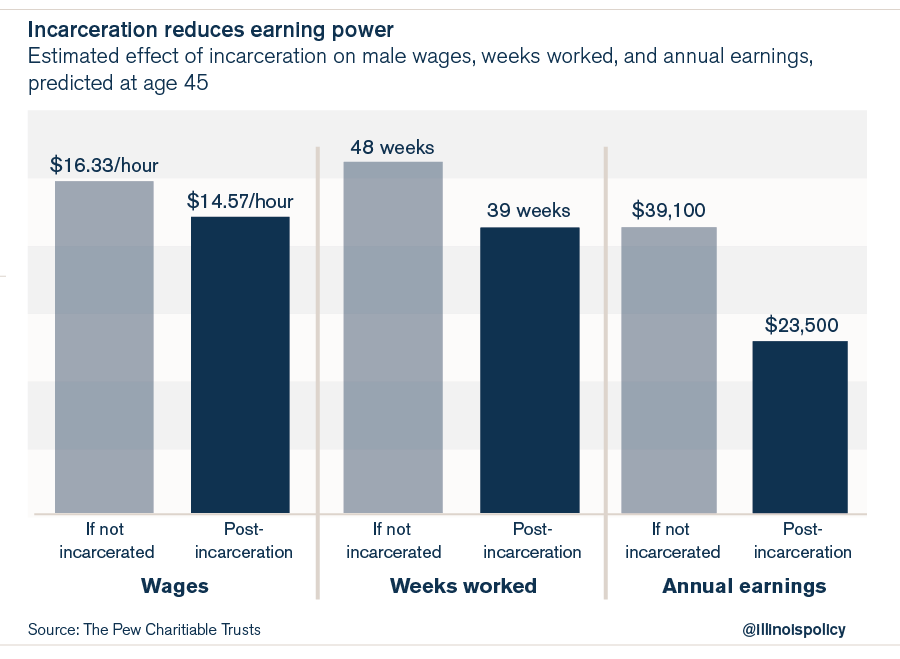

When government makes it excessively difficult for ex-offenders to find work, it exacerbates these problems. Even when former offenders can find work, they already have lower estimated annual earning power than the typical worker: An ex-offender will earn about $15,600 less per year than someone who has never been incarcerated, according to research by The Pew Charitable Trusts.20

While data on the exact number of unemployed persons with criminal records aren’t available, research shows former offenders are more likely to experience unemployment and underemployment than the general population. Survey data have suggested that as many as 60 to 75 percent of former offenders are unemployed a year after their release.21 This makes removing the barriers to work that limit options for people who’ve already completed their sentences all the more urgent.

One might also consider how much tax revenue Illinois foregoes while ex-offenders remain shut out of jobs. For example, Illinois’ per-capita income was $44,815 in 2012.22 For every former offender who can’t find a job, Illinois may be missing out on over $1,600 in state income-tax revenue, depending on exemptions, to say nothing of other tax revenue, such as sales taxes. (This estimate may be high, as data on the average salaries of employed former offenders in Illinois are very limited.)

The fiscal and societal costs of unemployment and underemployment among ex-offenders are staggering for former offenders, their families and the public. Illinois needs new approaches to bring down these costs.

Policy solutions to encourge successful re-entry for Illinois’ ex-offenders

Providing opportunities for ex-offenders to improve their situations must play a major part in Illinois’ approach to re-entry. To that end, a criminal record should not normally play a role in an ex-offender’s everyday life, except where absolutely and clearly necessary to protect public safety. After an offender has successfully served a sentence, the presumption should be that the offender has paid his or her “debt to society.”

As of Jan. 5, 2016, Illinois prisons held 45,938 persons.23 Almost half have previously served time in Illinois prisons. Research has shown that unemployment is a major driver of a return to crime, to say nothing of poverty. To stop the cycle of incarceration, Illinois needs to focus on removing barriers to work that keep too many former offenders out of legal employment. The following three proposals outline how Illinois can remove some key hindrances to re-entry and success after incarceration.

1. Sealing expansion

One major step Illinois can take to enable employment is to expand the ability of nonviolent offenders to apply for record sealing, also known as record nondisclosure in some jurisdictions. While expungement completely clears a criminal record from someone’s history, sealing, on the other hand, restricts who may view the record – usually limiting this to law enforcement, employers in certain sensitive industries such as education or finance, or by court order.

Across the country, at least 18 other states besides Illinois permit sealing or expungement of misdemeanor or felony records for adults.24 The scope of these policies vary significantly by state, but liberal and conservative states alike have expanded their use in recent years. New Hampshire, for example, allows nonviolent convictions to be annulled, but waiting times vary by offense between one and 10 years. While Massachusetts allows felony records to be sealed after 10 years.25 Utah allows petitions for sealing felony records seven years after an offense, and Texas passed legislation in 2015 allowing first-time offenders to have their records sealed, as long as their offenses were nonviolent and nonsexual.26, 27

Illinois currently has a limited sealing program, established by the Criminal Identification Act. Illinois law provides for the sealing of certain nonviolent Class 4 and Class 3 offenses – the two lesser categories of felonies, comprising offenses such as possession of cannabis and prostitution.28

Here’s how the process works: The sealing of a record happens through an adversarial process in the circuit court where the state initially brought criminal charges. For sealing-eligible crimes, an offender can petition the court that sentenced him or her, and a judge considers various factors such as the strength of the evidence supporting the initial conviction; the applicant’s age, criminal and employment history; the period of time between the crime and the petition for sealing; factors brought up in a prosecutor’s objection; and adverse consequences to the applicant if the court denies the sealing petition. Upon application, notice is given to the state’s attorney, state police, and any other relevant arresting authorities, which will have the opportunity to oppose the application if they think the offender poses a continuing risk to public safety and should not have his or her record sealed.

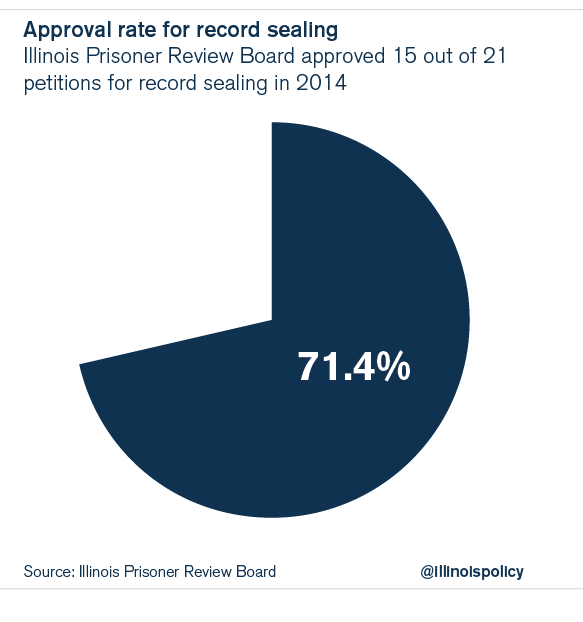

Data on sealing through the court system isn’t readily available because Illinois circuit courts do not maintain public records of how many sealing petitions they grant. But some limited information regarding the frequency of sealing-petition approval does exist. Record sealing can also occur through the Illinois Prisoner Review Board, an administrative agency with the authority to issue certificates of sealing under the Criminal Identification Act.29 In 2014, the review board received 21 petitions for sealing and granted 15, or 71.4 percent, of them.30 Only a small number of sealing petitions go through the review board, which in fact encourages people to apply for sealing relief through the courts. But the approval rate indicates that a genuine vetting process occurs for sealing applications – they aren’t granted automatically to everyone who applies.

The idea that former nonviolent offenders could limit viewings of their criminal records to law enforcement might worry some people. But there are already safeguards in place to address these concerns. For example, financial firms would need to know if prospective employees have committed any offenses related to fraud or embezzlement – and the law already provides for banking firms to see this information, even if a record is sealed.31 Schools are another field of employment in which knowing someone’s background may be critical – and schools also have access to all criminal records, even if they are sealed.32 Additionally, any kind of record not specifically addressed by statute could still be accessed through a court order if necessary.

The general rule, however, should be that the punishment for a conviction is the prison sentence, parole or probation served by an offender. For most nonviolent offenses, at least, the ex-offender should have the option to petition a judge for record sealing after serving his or her sentence. If a judge, with the agreement of law enforcement officials, determines that an offender has reformed, that ex-offender should have the chance to apply for work on the same grounds as anyone else – without the burden of a criminal record holding him or her back from employment.

Why it works

Expanding sealing eligibility works as a solution because it allows a nonviolent former offender who has completed his or her sentence to apply for jobs on a more equal footing if a judge and law enforcement believe that person does not pose a safety risk. This wouldn’t shorten anyone’s sentence or allow a person to escape paying the price for committing a crime. Judges vet every application. But this one change can help put more former offenders in a better position when applying for work, giving them a path to supporting themselves and their families without turning back to crime.

Sealing is also more business-friendly than “ban the box” reforms, which impose regulatory and reporting burdens on large and small businesses alike, as well as legal risks for noncompliance with the law:

“In Illinois … a public or private employer who has at least 15 employees cannot ask about an individual’s criminal history until the applicant has been selected for an interview or, if there is no interview, until they have been pre-selected for the job. This may seem straightforward; however, Chicago has a separate, tougher “ban the box” rule. Chicago’s ordinance applies to businesses with fewer than 15 employees, and also requires certain city agencies to take into account several factors prior to hiring individuals with criminal backgrounds — such as the nature of the offense, the applicant’s criminal history, and the age of the individual when convicted. The ordinance also forces small businesses to tell applicants who weren’t hired whether the decision was due to their criminal record. Thus, a business owner who has entities in and outside of Chicago must establish different hiring practices and training for each location to indemnify him- or herself from hefty fines and litigation.”33

But with sealing, former offenders can more easily obtain employment, and this happens without placing burdensome reporting requirements on employers. To make these changes a reality, Illinois should make three updates to the current sealing law:

- First, lawmakers should expand eligibility to apply for record sealing to most nonviolent offenses of any felony class.

- Second, lawmakers should eliminate the time an ex-offender must wait to be eligible to apply for sealing. After a prison sentence or parole has been successfully completed, a former offender should have the right to petition a court to have his or her record sealed.

- Third, the current law should be revised to presume that anyone with a nonviolent offense will be allowed to petition for record sealing unless the General Assembly chooses to specifically exclude that offense. This would be the opposite of the Criminal Identification Act in its current form, as only specific, listed offenses are now eligible for sealing.

2. Negligent-hiring liability reform

Many employers are willing to hire former offenders, but are concerned about the possibility of a negligent-hiring lawsuit if an employee commits an offense in the future.

Given that starting and running a business constitute a significant personal investment in financial resources, time and effort, it shouldn’t surprise anyone that business owners “are cautious and tend to overprotect themselves.”34 Employers’ concerns about the risk of negligent-hiring liability were the primary reason that trade organizations such as the National Federation of Independent Business and local chambers of commerce have expressed concerns about “ban the box” reforms.35

The stigma of a criminal record in private hiring is a real problem that policymakers need to address, but not in a way that forces employers to deal with unnecessarily burdensome regulatory requirements, or that relies on the threat of lawsuits to encourage hiring. Researchers have noted an increasing push toward litigation in recent years to challenge employers’ use of criminal background checks. But businesses can hardly be faulted for simply trying to protect themselves.

A more coherent approach would take the concerns of employers seriously by limiting the risk they face from negligent-hiring lawsuits. If done the right way, this would give employers the confidence to take a chance on a former offender, without fear of exposure to lawsuits as a result.

Several states have already taken a lead on this issue. Since 2010, Colorado, Connecticut, Minnesota, New York and Texas have passed negligent-hiring liability laws. Colorado’s law, for example, limits the use of an employee’s criminal record in lawsuits if an arrest didn’t result in a conviction, if the record was sealed or the person received a pardon, and, most importantly, if the conviction was unrelated to the facts of the case.37 Kansas, Louisiana, Massachusetts, North Carolina and Ohio also provide qualified immunity from lawsuits when a criminal record is the only evidence of negligence.38

Illinois, too, provides some negligent-hiring liability protection – but only for employers that hire former offenders who have been issued certificates of relief from disabilities. A certificate of relief from disabilities is issued after an assessment by a court and affirms that an offender is rehabilitated, makes him eligible for most business licenses, and provides protection from lawsuits to employers that hire the ex-offender.39 But this isn’t an ideal solution to the problem of hiring. First, not all former offenders can afford the money for a lawyer to handle the application process for the certificate, or the time to wait to be issued the license before looking for work. An ex-offender’s job-search process should be as streamlined as possible, and, whereas some procedural steps might make sense for record sealing, a complicated process should not be required to relieve private employers of liability when making their own hiring decisions.

Why it works

Fifty-two percent of employers conduct background checks because they are concerned about the risk of negligent-hiring liability, according to survey data collected by the Society for Human Resource Management.40 Employers are clearly concerned about lawsuits, and unless those fears can be assuaged, there’s little reason to think they would expose themselves to the risk of liability.

Some critics have argued that since the likelihood of a negligent-hiring lawsuit is low, there’s little need to address the issue in most states.41 But even if these lawsuits are rare, the threat is real enough that it has influenced hiring practices. And because not all former offenders will be eligible for record sealing, it is necessary to make it easier for employers to give those ex-offenders a chance at a job. Without employers’ willing participation, it will remain difficult for former offenders to overcome the stigma that discourages employers from hiring them.

To achieve this goal, Illinois lawmakers should pass legislation that limits an employer’s liability for hiring an offender with a record to cases in which:

- The employer knew of the conviction or was grossly negligent in not knowing of the conviction, and

- The conviction was directly related to the nature of the employee’s or independent contractor’s work and the conduct that gave rise to the alleged injury that is the basis for the suit.

Updating Illinois’ negligent-hiring law would also be fairer for employers and employees. Liability for an offense should lie with the person who commits it, not with an employer who gave that person a second chance. Those employers that do their due diligence in hiring should not have to worry about being made to pay for someone else’s conduct. By limiting hiring liability, lawmakers ensure individuals remain responsible for their own conduct – a critical point to emphasize for former offenders – while easing the transition to legal employment for ex-offenders re-entering society.

3. Occupational Licensing

One additional way Illinois can combat unemployment among former offenders is to expand occupational-licensing options. In Illinois, the state licenses 24.7 percent of the workforce.42 Excessive licensing itself poses problems for economic growth and development: It raises barriers to entry that both prevent people from finding employment and unfairly protect an industry’s established players from market competition.

But since nearly a quarter of the state’s workers need the government’s permission to work in their fields, it’s key that Illinois eliminate most of its restrictions that keep former offenders from these jobs. At least 118 state-level licenses either must or may not be granted to former offenders, and the categories are broad.43 The state can deny licensure to a former offender for professions such as barber, cosmetologist, dance-hall operator, geologist, dietician, roofer and sports agent. Licenses must be denied for occupations such as lottery ticket agent, mortgage loan originator, and health care worker.44 The restrictions cover a host of positions that do not have a public-safety element. Moreover, some licensing regulations do not even set a time period after which the restrictions can be lifted, in effect imposing lifetime prohibitions on ex-offenders’ obtaining many kinds of work.

There may be some cause for case-by-case license denials. No one wants to risk allowing a convicted child molester to teach children in a school, for example. But these examples are few and far between – and should not define the state’s general policy approach to granting licenses. The General Assembly can draft narrow rules to exclude dangerous persons from particular professions as needed.

Carefully tailoring Illinois’ restrictions to limited situations where public safety requires it could still protect vulnerable populations, but would also enhance career options for ex-offenders and thereby help lower the recidivism rate.

Why it works

If government controls entry to a quarter of all jobs in the state, as Illinois does, it has a unique ability to prevent former offenders from working in these fields. Removing these restrictions would give ex-offenders the opportunity to earn a living in many occupations from which they would otherwise legally be barred.

Illinois needs two major updates to its occupational-licensing regime:

- The presumption should be that once a sentence is completed, a former offender is restored to the same rights and privileges as any other resident of Illinois. To that end, licensing boards should be required to take sentence completion as evidence of rehabilitation for the purpose of issuing a license.

- Any statute that enacts licensing bans or restrictions that are necessary for public safety, such as certain jobs in schools or in other sensitive industries, should come with a time frame that will eventually allow any ex-offender to petition his or her sentencing court for the right to apply for a license. The only justification for continued legal disabilities is in narrow cases where particular offenders may pose unique public-safety risks if employed in specific professions. But the burden should always fall on the state to demonstrate that such a precaution is needed.

Conclusion

The reforms this report proposes offer a way to incorporate second chances into Illinois’ criminal-justice system after offenders have completed their court-mandated sentences – creating a path forward to rehabilitation and productive citizenship after incarceration.

The success of the state’s criminal-justice system is not measured simply by how many offenders it removes from the streets. It also needs to return offenders to communities as self-sufficient, productive people, able to support their families. If Illinois wants to meet the governor’s goal of reducing the prison population by 25 percent, lawmakers and reformers will have to pay as much attention to re-entry policy as they do to sentencing reform and front-end policy issues.

Illinois can and should hold offenders accountable. But once offenders have completed their sentences, the state must consider their debts repaid – and help clear the path toward economic opportunity.