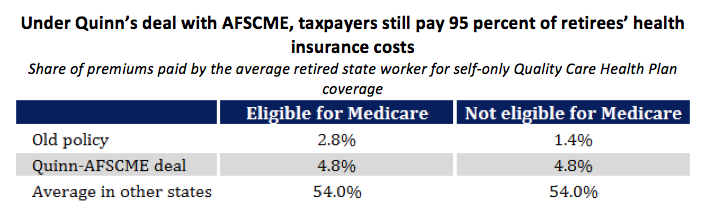

Under Quinn’s deal with AFSCME, taxpayers still pay 95 percent of retirees’ health insurance costs

For years, retired state government workers have contributed little or nothing toward the cost of their health insurance premiums. This sweetheart deal costs Illinois taxpayers roughly $1 billion a year, with costs continuing to climb year after year. The state’s unfunded liability for retiree health insurance is more than $54 billion. Lawmakers decided to do...

For years, retired state government workers have contributed little or nothing toward the cost of their health insurance premiums. This sweetheart deal costs Illinois taxpayers roughly $1 billion a year, with costs continuing to climb year after year. The state’s unfunded liability for retiree health insurance is more than $54 billion.

Lawmakers decided to do something about these ever-growing costs last year. But rather than set premiums through statute, the General Assembly did something new. It turned over authority of setting health insurance premiums for retired state workers to the governor’s office.

When we met with Gov. Pat Quinn’s policy team last spring, we shared our plan for reform, which Quinn was free to implement with his new authority. Our proposal, which state Rep. Ron Sandack, R-Downers Grove, sponsored as House Bill 3309, would have retired state workers pay an average of what retired state workers in other states pay, with premiums set on a sliding scale, according to retirement age, years of service and pension income. This would reduce the enormous burden on taxpayers while still rewarding employees for lifelong service, discouraging early retirement and protecting low-income retirees.

Having lost the fight lobbying against the law while it was pending in the legislature, American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees turned its attention to making sure Quinn bargained over the issue. As the union told its members after the deal was struck last week, the union bosses “fought to minimize the impact” of the law.

Of course, the law is very clear that Quinn was under no obligation to negotiate the changes at all. As details over the deal struck between AFSCME and Quinn are beginning to emerge, let’s review how it turned out.

Under the deal, there is zero connection between the retirees’ share of premiums and the actual cost to provide coverage. Instead, retired employees will pay premiums as a small percentage of their pensions. Folks who retired early and are not yet eligible for Medicare will pay 2 percent of their pensions toward premiums and those who are already on Medicare will pay 1 percent of their pensions.

Retirees in the state’s most popular health plan currently pay an average of 1.4 to 2.8 percent of the cost of their premiums for self-only coverage. Under the Quinn-AFSCME deal, these retirees will pay an average of 4.8 percent of the cost of their premiums.

Under Quinn’s deal with AFSCME, taxpayers still pay 95 percent of retirees’ health insurance costs

Share of premiums paid by the average retired state worker for self-only Quality Care Health Plan coverage

Consider this: the retired state worker who will pay the highest premium under the deal has an annual pension of more than $130,000. And even she would only pay 19 percent of the cost of her premiums.

Compare that with the private sector, where only 8 percent of retirees are even offered health insurance coverage through their former employers and typically pay all or most of the premiums when they do have access to retiree health insurance.

Quinn’s deal is also structured in a way that will incentivize retirees to choose Cadillac coverage over the less expensive HMO options. Because premiums are not tied to the actual cost of the plan selected, retirees will pay the same regardless of which plan they pick. They’ll have no incentive to choose a lower-cost option.

This perverse incentive could be quite costly. The difference in costs between the Cadillac plan and the average HMO is more than $2,400 per year for a retiree not yet eligible for Medicare. Taxpayers can expect to see some of the savings wiped out entirely by retirees switching to higher-cost plans.

Last year, lawmakers punted this issue to the governor. That maneuver clearly failed. It’s time they step up and do what they should have done in the first place: reform retiree health insurance benefits in a thoughtful, meaningful way. The U.S. Supreme Court says they have that power. It’s time they used it.