Progressive tax would introduce marriage penalty into Illinois tax code

Replacing Illinois’ fair, flat income tax with a progressive tax would mean that some married couples with both spouses working would pay more in state income taxes than if they remained single.

One of the virtues of Illinois’ flat income-tax structure is that it treats income the same whether it comes from a married worker or a single worker.

A progressive income-tax system, on the other hand, often involves marriage penalties and marriage bonuses. This structure bumps married couples into different tax brackets when they combine their income, compared to where they would have been if they were single. One of the many drawbacks of state Rep. Lou Lang’s progressive-tax scheme and others like it is that it would introduce the “marriage penalty” into the Illinois tax code.

Lang’s proposal, House Bill 689, is part of a bigger overall plan to change the Illinois Constitution to swap out the state’s fair, flat tax for a progressive income tax. First, the Illinois General Assembly would have to pass the constitutional amendment found in House Joint Resolution Constitutional Amendment 59.

With a constitutional amendment secured, Lang’s proposal would need to pass to set initial, progressive tax rates. The marriage penalty would kick in at higher income levels under Lang’s initial rates. Of course, Lang’s rates are only a starting position that would be subject to change if the constitutionally protected flat tax were removed. And indeed, state Sen. Don Harmon, D-Oak Park, the progressive-tax champion in the Illinois Senate, has already underscored the changeability of rates, explaining, “Nimbleness in tax policy is critical.”

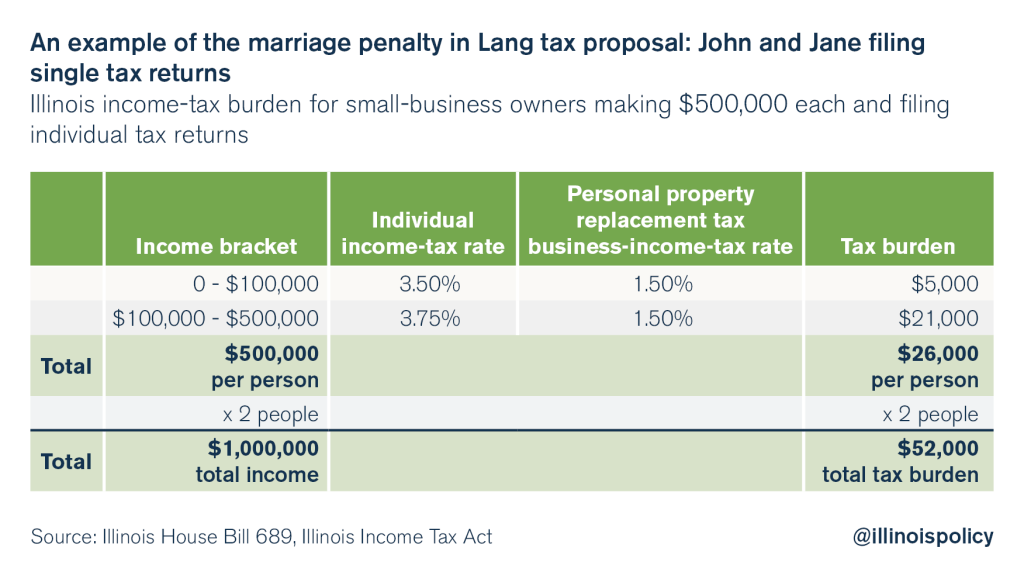

Setting aside how the rates might move, here’s a look at how the marriage penalty would work in Lang’s initial proposal. Suppose John and Jane are business partners who run a successful restaurant. They earn a profit of $1 million per year. Each partner would thus earn $500,000 per year in taxable income, and under Lang’s proposal each would each pay $26,000 in state income taxes, for a combined total of $52,000 in taxes between them.

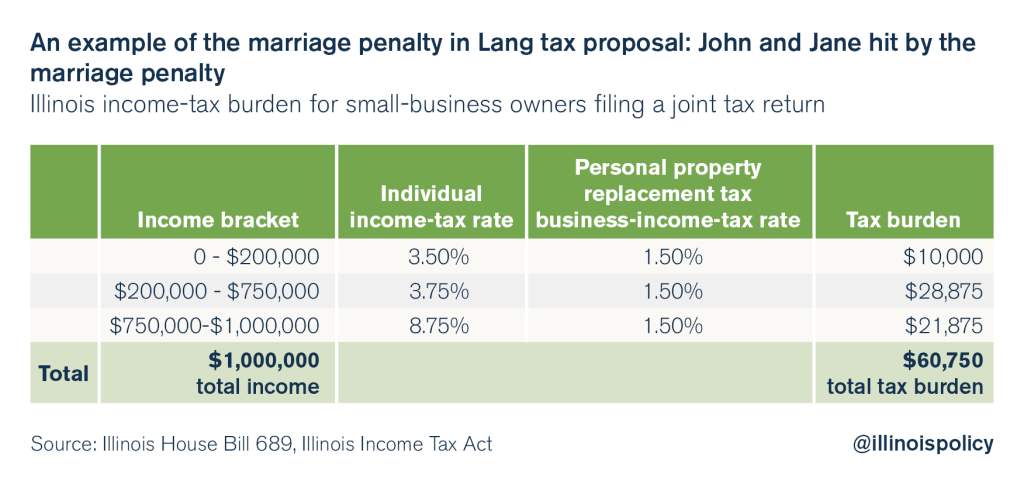

Now suppose restaurateurs John and Jane decided to get married. Instead of having $500,000 of business income each as individuals, they would have $1 million of joint income as a married couple. And instead of paying $52,000 in total taxes, Lang’s proposal would put them on the hook for $60,750 in taxes, a nearly $9,000 increase in taxes as a penalty for getting married. That’s because the marriage penalty embedded in Lang’s tax proposal would move some of John’s and Jane’s income into a higher income-tax bracket than if they’d never married.

If John and Jane opened up a second restaurant and doubled their income, their “marriage penalty” would increase to $12,500 per year from $8,750 per year. The more John and Jane succeed, the more they pay the marriage penalty.

The marriage penalty does not have much effect on whether people get married, but research does suggest the marriage penalty affects how much each spouse works once the couple marries.

And experience in Illinois shows the fewer tax tricks politicians have, the better. Just as the progressive-tax burden would likely creep down into lower income brackets after its institution, so too would the marriage penalty creep down to affect more and more couples with both spouses working.

Illinois politicians already manipulate the tax code to impose penalties on certain constituencies and dole out rewards to others. They should keep marriage out of it.