AFSCME: The 800-pound gorilla at the negotiating table

By Mailee Smith

AFSCME: The 800-pound gorilla at the negotiating table

By Mailee Smith

The American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees claims to be seeking a “fair contract” on behalf of Illinois state workers. But the power and influence exerted by the state’s largest government-worker union means the bargaining table almost always tilts in AFSCME’s favor.

The reality is that AFSCME is the power player in negotiations with the state. This power – and the contract perks that result – pits the union against the state’s taxpayers.

Illinois state workers are the highest-paid state workers in the nation when adjusted for cost of living. AFSCME workers receive platinum-level health care at low cost, and most get free health insurance at retirement. And then there are AFSCME perks – such as lax disciplinary procedures (no repercussions when a worker has 10 unauthorized absences) and overtime pay starting at 37.5 hours – that are unlike anything offered in the private sector.

Just how did AFSCME obtain all these contract provisions? At least three factors place AFSCME at an advantage over state taxpayers when it comes to bargaining for a new contract:

1. The nature of collective bargaining favors unions over employers.

Natural checks and balances on union demands exist in the private sector. Unions cannot demand more than a private company earns, or the company will go out of business and union workers will lose their jobs.

Not so in the public sector. There are no natural limits on AFSCME’s demands for more money or more benefits. The union can demand more because the state passes on all associated costs to the taxpayers, who have no choice but to pay. And the harm to the state’s economy of ever-higher taxes and debt to fund unsustainable government-worker benefits can take years or even decades to reach a crisis point.

What’s more, government-worker unions have a monopoly. There is one source for government services. If an Illinois resident is displeased with those services, he cannot simply obtain them from a different state government. And when a government-worker union threatens to strike, it is threatening to shut down government services, generally leaving residents with no competing provider of those services.

2. AFSCME’s political contributions warp the negotiating process.

Political contributions mean power.

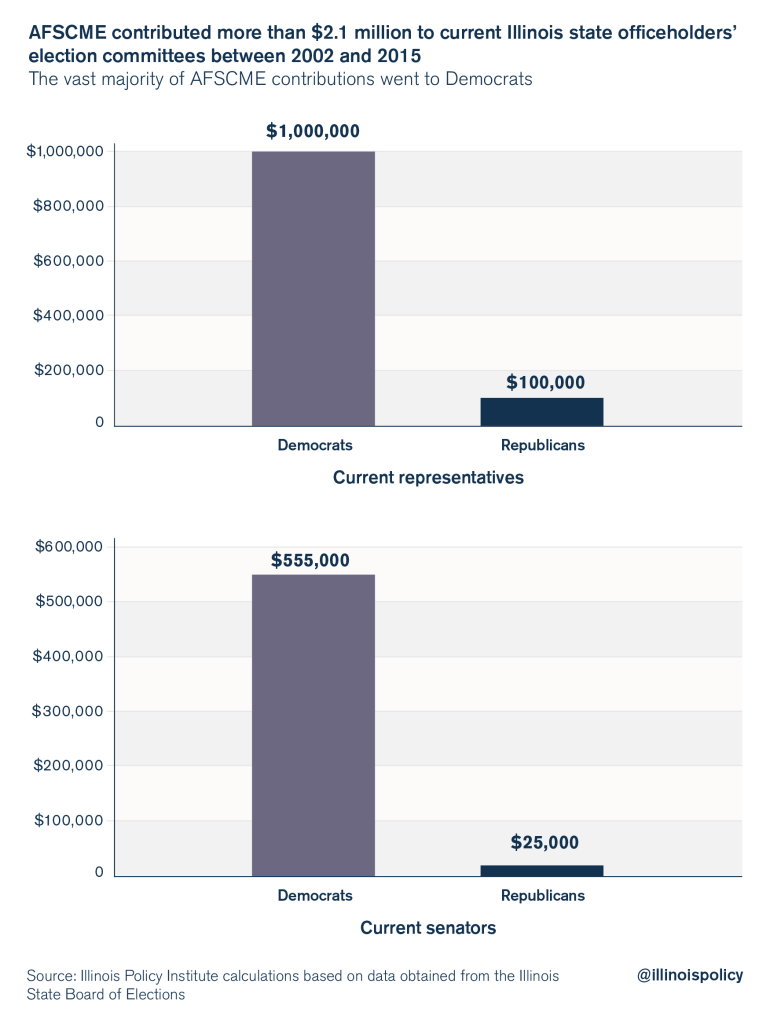

Between 2002 and 2015, AFSCME gave more than $2.1 million to the election committees of current officeholders – including the majority of current state senators and representatives in the General Assembly. As of late September 2016, AFSCME had already given over $1.4 million to political campaigns in 2016 alone.

AFSCME leverages these contributions to push union-friendly governors and lawmakers into contract provisions and policies that benefit the union.

Case in point: AFSCME donated hundreds of thousands of dollars to former Gov. Pat Quinn. During negotiations for the last contract, Quinn initially sought cost-saving provisions – but he caved to AFSCME demands, leaving taxpayers with a contract that cost even more money in salary and benefits than the previous contract.

AFSCME’s political power means taxpayers are not represented by elected officials who have only taxpayers’ interests in mind; rather, taxpayers are represented by politicians who are indebted to AFSCME for their elected positions.

3. AFSCME negotiates for contract provisions that give the union even more power.

Even the collective bargaining agreement itself gives the union an unfair advantage over taxpayers.

Imagine an employer paying an employee – and allowing him to use employer facilities – to work against the employer. It sounds preposterous, but that is exactly what the contract provides to AFSCME:

- Employees are allowed time off – with pay – to perform union work.

- Employees are allowed time off – with pay – to learn how to become union stewards.

- Employees are allowed time off – with pay – to attend union orientation.

On top of all of that, the state is required to provide rooms for union meetings; it must provide the use of state phones; and it must grant access to state email systems, as well as to information about employees who are not union members. Taxpayers are actually paying state employees to use state resources to advance union causes to the detriment of state taxpayers.

Each of these three factors places AFSCME in a more powerful position than state taxpayers when it comes to negotiations. Taken together, they place AFSCME on a totally different plane.

Introduction

The labor movement – and the rise of unions in the workforce – developed because of the poor working conditions present during the Industrial Revolution.[1] Low wages, long hours and dangerous working conditions were prevalent. Unions were seen as a way to prevent companies from exploiting workers.[2]

But that’s a far cry from what government-worker unions have become across the United States, and particularly in Illinois. These powerful unions have secured lavish benefits for state workers. For example, Illinois state workers are the highest-paid state workers in the nation when adjusted for cost of living.[3] Many state employees work just 37.5-hour workweeks before earning overtime.[4] And the workplaces and work hours of the thousands of state workers employed in white-collar positions are hardly comparable to the conditions that gave rise to labor unions, such as those faced by 19th century factory workers or coal miners.[5]

In fact, now it seems there has been a situation reversal: Government-worker unions hold disproportionate power, and taxpayers need protection from exploitation. In effect, the influence government-worker unions wield in Illinois has enabled them to create a system of “haves” and “have-nots.”

The haves – government workers – enjoy exorbitant benefits and increasing salaries that outpace what private-sector workers receive.

The have-nots – the taxpayers, whose own salaries have stagnated in recent years – have to foot the bill for ever-increasing union demands. And unfortunately, the taxpayers must depend on elected officials to represent their interests at the bargaining table – officials whose political fortunes are often closely tied to the unions with whom they are supposed to be negotiating.

The American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees – the largest government-worker union in Illinois – provides the perfect illustration of how government-worker unions have driven a wedge between state workers and state taxpayers. In addition to the fact that Illinois state workers are the highest-paid state workers in the nation when adjusted for cost of living,[6] state workers represented by AFSCME receive platinum-level health care at a low cost.[7] Most AFSCME workers also get free health insurance at retirement, a benefit worth $200,000 to $500,000 per employee.[8] And when Illinois’ contract with AFSCME expired in June 2015, the median AFSCME salary was $63,000 – compared to just under $32,000 in the private sector. In fact, the median income for an individual AFSCME worker is higher than the median income for an entire household in the private sector (just under $58,000 in 2014).[9]

The benefits AFSCME employees rake in are not limited to salary and benefits. Through the state’s collective bargaining agreement, workers are also entitled to other perks that are unlike anything offered in the private sector.[10] These include lax disciplinary procedures (such as no repercussions when a worker has 10 unauthorized absences), overtime pay that starts at 37.5 hours, and double-time and sometimes double-and-one-half time for working on holidays.

These lavish contract provisions raise the question: What makes it possible for a government-worker union to amass such perks?

Through collective bargaining, AFSCME has been allowed to strong-arm the state into meeting the union’s demands. At least three significant factors contribute to AFSCME’s ability to do so:

- The nature of collective bargaining and the rise of government-worker unions favor unions over employers. Because of differences between private employers and government employers, it originally was deemed unseemly for government workers to unionize. But the 1960s and 1970s brought the rise of government-worker unions, and with that proliferation came a wedge between state workers and state taxpayers – with the former having much more weight in the bargaining process than the latter.

- AFSCME’s political contributions warp the negotiation process and make the union the power player in contract negotiations with the state. AFSCME has contributed millions of dollars to current state officeholders, and AFSCME exerts this monetary influence to pressure lawmakers to accept contract provisions and push forward policies that benefit the union.

- AFSCME’s contract with the state gives the union even more power. Provisions within the collective bargaining agreement itself guarantee AFSCME even more power. Examples of these provisions include “release time” clauses, which require the state to pay workers for doing union work. In effect, these provisions require the state to pay workers to work against state taxpayers. And while the union has secured for itself the privilege of using state facilities and personal worker information to leverage its messaging, the state itself has to remain “neutral.”

Each of these factors alone would place AFSCME in a powerful position in bargaining for contract provisions. Taken together, they place AFSCME on a totally different plane.

This power – and the resulting contract perks – pits AFSCME against the state’s taxpayers. In reality, although it’s AFSCME versus the governor at the negotiating table, it’s AFSCME versus Illinois taxpayers when it comes to paying for the resulting contract provisions. And unfortunately, AFSCME holds vastly more power in this regard.

Collective bargaining: Government-worker unions’ advantage over employers

Understanding the source of AFSCME’s tremendous power requires a look at the nature of the collective bargaining process itself, and the way in which it can favor unions over employers. Originally, such bargaining was limited to the private sector: It was widely considered inappropriate for government workers. But government-worker unions began to proliferate in the 1960s and 1970s, pitting government workers against taxpayers.

Collective bargaining with private- and public-sector unions

The phrase “collective bargaining” is a term of art with a specific meaning in the labor context. The U.S. Department of Labor defines “collective bargaining” as “[t]he determination of wages and other conditions of employment by direct negotiations between the union and employer.”[11] Simply, collective bargaining is the negotiation process that goes on between an employer and the union that has been selected by employees to represent them in the negotiations. The employer and the union are bargaining for terms of a contract, such as wages and benefits. The contract itself is referred to as a “collective bargaining agreement.”

Collective bargaining is regulated differently depending on whether a union represents private-sector employees or public-sector employees. “Private sector” refers to the part of the economy that is not controlled by a government entity. In Illinois, a prime example of a private-sector union is the United Automobile Workers, or UAW. Among many groups of employees represented around the nation, UAW represents unionized Caterpillar employees in contract negotiations with the equipment manufacturing company. Private-sector collective bargaining is regulated under federal law.

“Public sector” refers to the part of the economy that is controlled by federal, state or local governments or entities. As such, unions in the public sector are frequently referred to as government-worker unions. AFSCME, which represents 35,000 state workers, is the prime example of a public-sector union in Illinois. These workers include anyone from interns to administrative assistants to physician specialists.[12] Public-sector collective bargaining is regulated under state law.

Collective bargaining in the private sector

Collective bargaining in the private sector is governed by the federal government through the National Labor Relations Act, or NLRA. Enacted in 1935, the NLRA’s main purpose is to protect the legal rights of employees to engage in union and collective bargaining activities.[13]

Because the NLRA’s focus is more on employee or union rights than on the rights of the employer, “the legal restrictions on labor unions’ dealings with employees are less intrusive than those on employers’ relationships with employees.”[14] Put another way, the NLRA tends to favor the union more than it does employers.

For example, the NLRA places restrictions on employers when employees begin organizing, or working toward unionization, in the workplace. Section 8(c) of the NLRA provides that employers cannot express any views, arguments or opinions that contain threats of reprisal, force or promise of benefit.[15]

Over the years, the acronym “TIPS” has been developed to summarize what this means. Employers cannot use threats, interrogation, promises, or surveillance while employees are organizing a union in the workplace. On their face, such prohibitions may seem reasonable. But in application, they are nothing more than restrictions that favor unions over employers.

For example, an employer cannot make statements about discontinuing benefits or falling pay if employees unionize[16] – even if that is the likely outcome due to budgetary pressures from the extra expense of a unionized workforce. Likewise, an employer cannot promise better benefits if the employees choose not to unionize.[17] Not only does this inhibit employer speech, but it could also disadvantage employees who stand to benefit from such a promise. And the surveillance prohibition means that management should never attend a union meeting, even if invited.[18]

Conversely, restrictions on union speech are not nearly so intrusive. Unions can use promises, scare tactics and significant workplace pressure to drive employees toward unionization or going on strike.

The National Labor Relations Board, or NLRB consistently holds that employers violate the NLRA by promising or granting benefits to employees if they do not unionize. But it also consistently holds that union promises of the benefits and improvements the union can achieve are not coercive – and, therefore, allowed under the Act.[19] For example, the NLRB upheld the following communication from a union to workers during a unionization campaign:

Remember when Local 223 is elected on April 19th you will no longer have to pay for you and your families [sic] medical benefits. As a Local 223 member you will be entitled to free medical care, free hospitals, free dental care, free optical care and eyeglasses not only for you but for your immediate family members as well. And nothing will be taken out of your paycheck to pay for those benefits.[20]

Of course, such promises are empty because the union cannot guarantee ahead of time what will be achieved through collective bargaining negotiations. But despite the falsity of the union’s claims, the NLRB simply concluded that “[e]mployees are generally able to understand that a union cannot obtain most benefits automatically by winning an election but must seek to achieve them through collective bargaining.”[21]

This legal dichotomy – wherein the employer is prohibited from promising benefits (even if it can guarantee those benefits) while the union is allowed to make empty or even completely false promises – is entrenched in labor law.[22]

The Chicago Teachers Union, or CTU, provides a recent public-sector example of the type of legal pressure unions can exert against their members to advance a union cause. In September 2016, teachers in the union voted on whether to authorize a strike. But instead of conducting the vote through a secret ballot election, the union asked teachers to authorize the strike via open petitions circulated through the schools. This tactic allowed teachers to see how their colleagues voted, applying undue influence on those who disagreed with the strike and wished to vote “no.” In fact, the union’s scare tactics caused the editorial board at the Chicago Tribune to compare CTU’s obtaining an overwhelming level of support for a strike to the “election-in-name-only” victories of former Iraqi President Saddam Hussein and North Korean dictator Kim Jong Un.[23]

Collective bargaining in the private sector does have some practical checks and balances that help inhibit unions from demanding too much. For example, there are monetary constraints on employers – unions cannot demand more from the employer than it can afford to pay, or everyone could be out of work.

Case in point: Striking bakery workers drove iconic Hostess Brands LLC to close in 2012, triggering the closure of the company’s 33 bakeries, 565 distribution centers and 570 outlet stores.[24] Then-CEO Gregory Rayburn explained that the company simply did not have the financial resources to weather an extended nationwide strike. The closure affected 18,500 workers.

But as is examined below, the same type of checks and balances are absent in the public sector. Governments don’t permanently shut down or immediately go bankrupt because unions demand more money; instead, taxes go up and taxpayers bear the burden.

It is under this construct – a federal law that regulates private-sector unionization and collective bargaining in a way that tends to favor the union over the employer – that one must examine the role of government-worker unions.

Collective bargaining in the public sector was never meant to be

Historically, it was understood that there was no place for unions to represent government workers. There is a clear distinction between the nature of public-sector unions and the nature of private-sector unions.

First, Congress passed laws promoting collective bargaining in the private sector because of the concern that private employers would exploit workers – through long hours, poor wages, dangerous working conditions, etc. – to increase profits.[25] For example, the United Mine Workers of America claims it was founded to bring coal miners out of horrible conditions and unregulated mines.[26] In 1898, the union secured its first contract, which guaranteed wage increases and an eight-hour day, among other provisions.[27]

But such a purpose is inapplicable to government workers. The government earns no “profits.” Most government jobs are not dangerous, nor do they exist under horrible conditions. What’s more, the majority of union members in the United States are now professionals, such as teachers, nurses and engineers.[28]

For example, AFSCME represents approximately 35,000 state government workers throughout Illinois. These government employees work in the state’s many agencies and departments, such as the Illinois Department of Human Services and the Illinois Department of Revenue, and, therefore, include various positions from well-paid interns to administrative assistants to physician specialists and civil engineers.[29] And when Illinois’ contract with AFSCME expired in June 2015, the median AFSCME salary was $63,000 – compared to just under $32,000 in the private sector. In fact, the median income for an individual AFSCME worker is higher than the median income for an entire household in the private sector (just under $58,000 in 2014).

Second, there is no competition within the public sector. The public sector is a monopolist.[30] There is one source for government services. If an Illinois resident is displeased with the services the state provides, he cannot simply choose to seek those services elsewhere, barring a move to another state. If a resident is displeased with the operations of a local city government, he cannot choose to receive those services from the next town over. The private sector, on the other hand, is competitive. If a consumer is unhappy with a service provided by a private business, he or she can shop elsewhere.

This monopolistic setup compounds the public-sector union problem when government workers decide to strike. Strikes or other work stoppages by government workers can cripple state and local governments and shut down public operations and services. This has an obvious detrimental impact on residents.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, the very nature of public-sector unions pits the union against the taxpayers. When public-sector unions bargain for higher wages and greater benefits, they are demanding that taxpayers pay more. In the private sector, increased union salaries and benefits are reflected in the services a company provides; costs go up and are passed on to the consumers, or the employer eats the costs and earns less profit, or a combination of the two. If costs go up, consumers can decide to do business elsewhere. Unions are bargaining against the employer, not against the consumer.

There is a natural check on union demands in the private sector. Union demands are limited by the company’s profit capacity and other competition in the marketplace. As seen in the Hostess example, if a union demands too much, a company will eventually crumble, and union workers will lose their jobs.

There is no such check in the public sector. In the public sector, the high costs of unionization are passed on to taxpayers – who have no choice but to pay.

It was the belief that unions have no place in government that led President Franklin Delano Roosevelt to say:

All Government employees should realize that the process of collective bargaining, as usually understood, cannot be transplanted into the public service. It has its distinct and insurmountable limitations when applied to public personnel management. The very nature and purposes of Government make it impossible for administrative officials to represent fully or to bind the employer in mutual discussions with Government employee organizations. The employer is the whole people …

Particularly, I want to emphasize my conviction that militant tactics have no place in the functions of any organization of Government employees. … Since their own services have to do with the functioning of the Government, a strike of public employees manifests nothing less than an intent on their part to prevent or obstruct the operations of Government until their demands are satisfied. Such action, looking toward the paralysis of Government by those who have sworn to support it, is unthinkable and intolerable.[31]

Early union leaders also indicated that unions have no place in the public sector. In 1955, AFL-CIO President George Meany said it is “impossible to bargain collectively with the government.”[32] And as far back as the 1880s-1890s, Samuel Gompers, the first president of the American Federation of Labor, sought to keep a separation between unionism and partisan politics.[33]

But those warnings were not heeded. In the 1960s, states began enacting laws that allow and regulate collective bargaining for government-worker unions.[34] By 1970, about half of state workers across the nation had gained collective bargaining privileges.[35]

Illinois joined those states in 1983, when it enacted the Illinois Public Labor Relations Act (mandating collective bargaining for government employees), or IPLRA, and the Illinois Educational Labor Relations Act (mandating collective bargaining for public school employees), or IELRA.[36] AFSCME is guaranteed collective bargaining privileges under the IPLRA.

In large part, the IPLRA and the IELRA are based upon federal law and the NLRA. In fact, when considering the IPLRA, the Illinois General Assembly expressly stated that it intended to follow the NLRA.[37] But the legislative history does indicate that certain employees – such as managers and supervisory employees – were excluded from unionization under the IPLRA to put the government on a more even footing with unions than employers have under the NLRA.[38]

Documents published after the enactment of the IPLRA report that the Assembly was “concerned with [the state’s] right to have someone on its side of the bargaining table.”[39] But even then, it was acknowledged that the IPLRA places a limitation on management’s rights when a policy “directly” affects wages, hours and terms and conditions of employment.[40]

With practically all contractual matters falling under those broad categories, the state is restrained from making taxpayer-friendly decisions about its workforce without first having to agree on those policies with a union. And the union, of course, has its own interests in mind, and it has the right to strike – it can threaten to disrupt state services if its demands are not met.[41]

Regardless of whether the General Assembly intended to place the government and the public-sector unions on similar footing in the collective bargaining process, time has demonstrated that they are not evenly matched. Public-sector unions make the negotiating process inherently political. And the political nature of government-sector unions has warped the bargaining process in Illinois in favor of government-worker unions. As a result, there is often no one truly representing taxpayers at the negotiating table.

Union political contributions’ distortion of the negotiation process

Labor unions have strayed a long way from their origins in the private sector. Now public-sector unions operate as political machines, helping to elect union-friendly politicians and then pushing those politicians to agree to generous contract provisions and labor policies. One national labor expert accurately refers to unions as “labor cartels.”[42]

AFSMCE provides the perfect illustration for why government workers should not be unionized. AFSCME has provided millions of dollars in contributions to the election campaigns of current state officeholders responsible for making labor policy decisions that affect government workers statewide. Yet other business entities that hold contracts with the state are prohibited from making any contributions – of any size – to officeholders who make decisions applicable to those entities. That stands in stark contrast to the millions of dollars AFSCME places in the hands of its political friends.

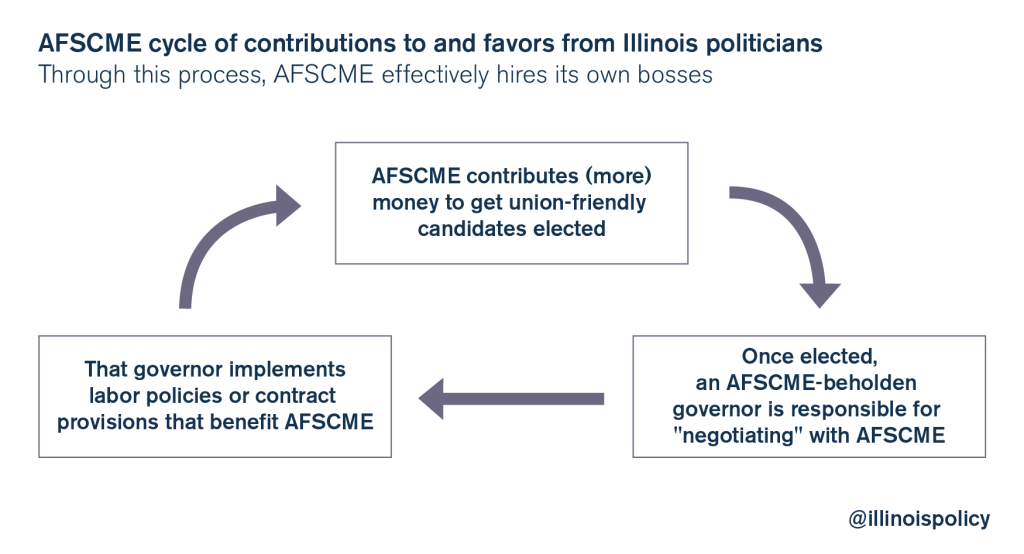

AFSCME then leverages the political power of those contributions to pressure governors and lawmakers into contract provisions and policies that benefit the union. In effect, this construct allows AFSCME to hire its own bosses. When the union comes to the bargaining table to negotiate a new contract, it is typically sitting across from a governor its campaign contributions helped to elect.

AFSCME’s money: AFSCME gave more than $2.1 million to current politicians’ election committees between 2002 and 2015 – and over $1.4 million in races to date in 2016

The political power AFSCME holds over state officeholders means taxpayers are not represented by elected officials who have their best interests in mind; taxpayers are represented by politicians who are indebted to AFSCME for their elected positions. While individual taxpayers may contribute to candidates, they do not do so as a unified bloc, and thus the power they might have from their donor status is diluted compared with a large single-source donor such as AFSCME.

That may sound dramatic, but the numbers illustrate AFSCME’s political influence – and demonstrate that AFSCME lavishes its money on friendly lawmakers who will push union-friendly policies.[43]

AFSCME contributed more than $2.1 million to current officeholders’ election committees between 2002 and 2015. The union gave more than $1.1 million to the election committees of current state representatives (with more than $1 million sent to Democrats). During that same time period, AFSCME contributed almost $580,000 to the election committees of current state senators (with more than $555,000 of that amount going to Democrats). The union sent even more money to the election committees of other current state officeholders. All of these additional recipients were Democrats – including Illinois Attorney General Lisa Madigan, whose own election committee received $207,000 from AFSCME.

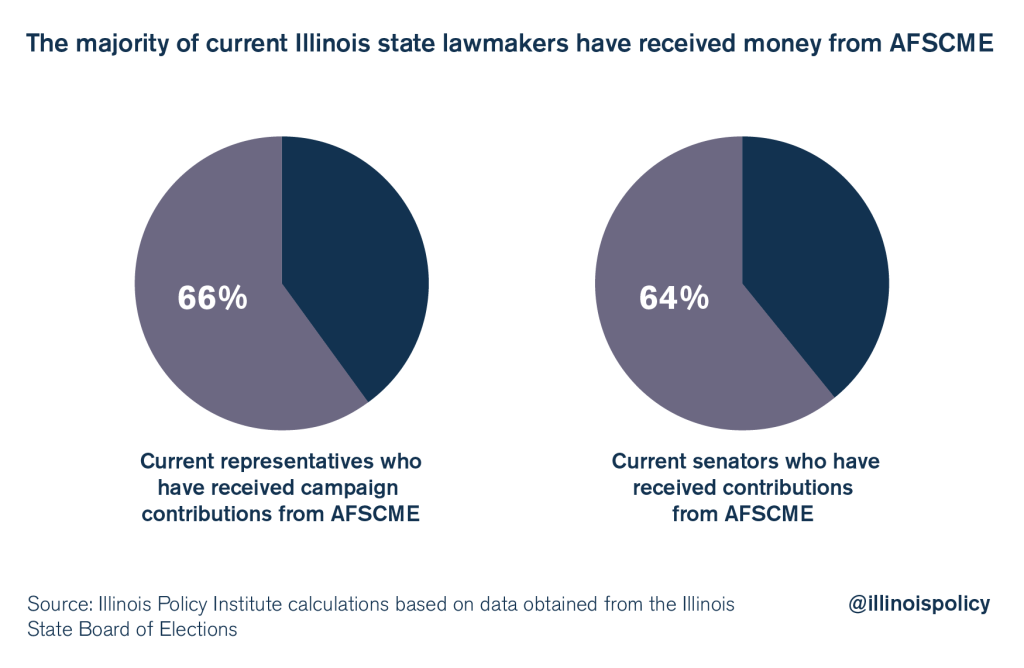

The numbers are particularly telling when focused on current state lawmakers. More than 66 percent of current representatives have received campaign contributions from AFSCME. Likewise, more than 64 percent of current senators have accepted contributions from AFSCME.

To put these numbers into perspective, consider the Illinois statute that prohibits certain business entities from making campaign contributions.[44] That law prohibits contractors who have $50,000 worth of contracts with the state – a fairly low threshold given the expense of construction and building work – from contributing to the election campaign of any officeholder who awards applicable contracts.

So while a business holding a contract with the state is prohibited from making campaign contributions, AFSCME can donate millions of dollars to the political campaign of the governor sitting across the table during negotiations. That’s a large monetary impact and a significant position of power.

These numbers do not take into account 2016, which is proving a harshly competitive election year. As of late September, AFSCME had already given over $1.4 million to political campaigns in 2016 alone.

AFSCME’s lobbying: AFSCME exerts its monetary influence on state officeholders

AFSCME’s political presence has benefited the union in negotiations for its contracts with the state, as past governors have kowtowed to AFSCME’s demands. Prior to Gov. Bruce Rauner taking office, AFSCME and the state reached agreements on more than two dozen collective bargaining agreements under the administrations of six different governors.[45] These agreements worked to give the union significant pay raises and benefit increases, often in times of statewide fiscal strain.

For example, under the administration of Gov. Pat Quinn, the state already was facing a dire financial situation. There was a budget deficit of $507 million for fiscal year 2012, a projected $818 million shortfall for fiscal year 2015, and the state had $7 billion in unpaid debts.[46] Quinn initially came to the table seeking concessions from AFSCME, such as eliminating contract language that gave workers automatic annual salary increases.[47] But Quinn caved and agreed to wage increases that cost the state $202 million between 2012 and 2015, in addition to the cost of other benefits.[48]

Not coincidentally, Quinn is currently the all-time highest recipient of AFSCME campaign contributions – totaling over $715,000 between 2002 and 2014. In total, he received over $11 million in contributions from government-worker unions during that time.[49] Similarly, former Gov. Rod Blagojevich received over $375,000 in AFSCME contributions – and a total of over $3.5 million from government-worker unions combined – during the same time period.[50]

The cycle of political contributions and political “favors” is fairly easy to follow. AFSCME contributes considerable amounts of money to a gubernatorial candidate. Once elected, that governor sits across the table from AFSCME in contract negotiations, supposedly representing “the people.” But that governor is beholden to AFSCME and its contributions for his position, and the governor implements labor policies or contract provisions that benefit AFSCME. AFSCME contributes more money. And the cycle continues.

But Rauner interrupted this cycle: He was elected without contributions from AFSCME or its affiliates.[51] AFSCME, unaccustomed to negotiating with a governor not beholden to it, refuses to compromise on a new contract.

But recent history reveals that AFSCME’s political power is not limited to pressuring state governors. There are clear demonstrations of AFSCME’s heavy-handed lobbying in the legislature. Without a governor in its pocket to sign off on the union’s demands, AFSCME has turned to its friends in the General Assembly in an attempt to get what it wants out of state taxpayers. In 2015 and 2016, politicians in the Illinois General Assembly passed AFSCME-backed legislation that would have altered state bargaining laws to further favor unions over the state.[52] Rather than allowing Rauner to represent taxpayers at the negotiating table, the legislation would have turned that power over to an unelected third-party arbitrator to determine the terms of the next AFSCME contract. The taxpayers would have no representation. Tellingly, this legislation would have been in effect only for Rauner’s term and would not have affected AFSCME’s negotiations with future governors from whom it might expect a better deal.

Rauner ultimately vetoed both bills, but the fact remains that AFSCME induced a majority of Illinois representatives and senators to support the bills. In short, when AFSCME didn’t get its way at the negotiating table as it had with past governors, it sought to legislatively remove the governor standing in its way.

AFSCME contract provisions: Source of additional union power

The nature of collective bargaining and the political power of government unions play out in the negotiation process. Not only does this power allow AFSCME to negotiate incredible salaries and benefits for state workers, but it also allows AFSCME to secure even more power for itself through the provisions of the collective bargaining agreement.

In its contract with the state, AFSCME has obtained a number of provisions that allow the union time and space to conduct union work. In many instances, union members are actually paid by the state while performing union work. That means the state – taxpayers – is paying employees to work against the state.

The absurdity of such provisions is obvious when applied to the private sector. Nationally, only 7.4 percent of private-sector workers are represented by a union.[53] In Illinois, only 10.1 percent of workers in the private sector are represented by a union.[54] This means the vast majority of employees in the private sector are nonunionized and therefore not subject to release-time clauses like those found in the AFSCME contract. And the idea of requiring private-sector employers to provide time, space and money for a group of employees to work against the employer is preposterous.

Release time to conduct union work

The most obvious examples of contract provisions providing power to the union are the “release time” clauses in the AFSCME contract. Generally speaking, “release time” occurs when a union member or representative is allowed time off from work to pursue a union project or priority.

For example, the collective bargaining agreement states that union representatives, union stewards and other eligible employees must be allowed time off – with pay and during work hours – to attend negotiations pertaining to their own state agencies or facilities, various committee meetings and grievance hearings.[55]

In sum, these employees are being paid, by state taxpayers, to step away from their jobs to conduct union activities. In fact, the contract explicitly states that “[a]ny time off with pay … shall be at the employee’s regular rate of pay as though the employee were working.”[56] But the employee is not working – not for the state, anyway.

In addition, employees are allowed up to two days off – with pay – to attend “certified stewards training.”[57] This means the state is paying employees to go through union training to become representatives of the union. These representatives will, in many instances, end up working against the state in union activities and negotiations.

Similarly, new employees are allowed time off – with pay – to attend union “orientation.”[58] Once again, employees are paid by the state to attend a union gathering that serves only union purposes. Because of the nature of collective bargaining in the government workplace, there is no check on the union’s speech during that time. And while the union can use that time to disparage the state or the governor and incite new employees to join the union, the state is not allowed a similar freedom to gather employees for the purpose of presenting its side and discouraging union membership.

Finally, union representatives also are allowed time off for a number of other activities, such as state or areawide committee meetings, union training sessions, statewide contract negotiations, and state or international conventions.[59] Time off for these particular activities is not paid, but employees do continue to accumulate seniority, continuous service and creditable service during this time. So while an employee representing the union at a state committee meeting may not receive monetary payment from the state for his time off from his state job, he would continue to accumulate benefits like vacation days and sick days while doing union work.[60]

Leave of absence to hold union office

In addition to release time, the AFSCME contract also provides an explicit, extended leave of absence to conduct union work.[61] Up to 30 employees at any one time shall be granted leave for the purpose of service as representatives or officers with the international, state or local AFSCME affiliates. Such leave is granted for a period of up to two years. Leave will be granted as long as the employee gives the state just five (working) days’ notice before going on leave, and the leave will not “substantially” interfere with the state’s operations. During those two years, the employee will continue to accumulate seniority and continuous service.[62]

As with the release time provisions, this leave of absence allows the union to utilize state employees for its own agenda and purposes. In the meantime, the state employee will continue to accumulate seniority. An employee can be gone for two years and come back to a job with the state. And because his seniority had continued to accumulate, he may have higher seniority than other employees who were working for the state during that time.[63]

Use of state facilities

Under the AFSCME contract, the state must make available state conference and meeting rooms for union meetings.[64] Thus, the union is allowed state meeting rooms to conduct union business that in all likelihood will never benefit the state. Again, applying that scenario to a nonunionized workplace demonstrates its absurdity. Forcing an employer to provide workspace for an organization that is working against it is ludicrous – but that is exactly the type of power AFSCME has secured for itself through its contract with the state.

The contract also provides that AFSCME representatives and officers have “reasonable access to the premises of the [e]mployer,” and the state is to provide bulletin boards or space at each work location for “sole and exclusive use” of the union.[65]

A separate section in the contract details the process for the handling of employee grievances, or complaints, against the state. In that section, the union is allowed the use of state workspace, state phones, and email to investigate or process those grievances against the state.[66]

Access to personal information of employees

The contract provides that the state is to notify the union of certain “personnel transactions”[67] involving “bargaining unit employees,” including the following:

- New hires

- Promotions

- Demotions

- Checkoff revocations[68]

- Layoffs

- Leaves and returns from leave

- Suspensions and discharges

This information is to be provided to the union in writing and “[a]t least once each month.”[69] Each transaction reported to the union must also include the employee’s Social Security number.

What’s more, the information required is not limited to transactions involving union members, but applies to all “bargaining unit employees” – even if they have opted out of the union and are fair share payers.

In addition, the union can request – and shall be allowed to use – state electronic mail on a semiannual basis to solicit personal email addresses of all AFSCME-represented employees.[70] Again, this includes members and nonmembers alike.

In sum, AFSCME’s contract with the state explicitly allows AFSCME to obtain personal information about both members and nonmembers, as well as to use state email systems to communicate with all employees. Not only is this an infringement on the privacy of workers who do not want to associate with the union, but it also provides a significant opening for AFSCME to utilize personal employee information and state email systems to pursue its own agenda.

Limits on state speech

Like most union contracts, the AFSCME contract includes an “employer neutrality” provision. This provision holds that the state “will not oppose efforts by any of its employees to be represented by a union.”[71] In effect, this provision prohibits the state from speaking out against union organization or membership. Yet there is no provision requiring union speech to remain neutral in regard to union organization or negotiations.

Conclusion

AFSCME’s power in Illinois cannot be overstated. The union-favoring nature of collective bargaining, AFSCME’s extraordinary campaign contributions and pressuring of recipient lawmakers, and the contract provisions it has negotiated for itself that provide the union even more power guarantee AFSCME is not the underdog in negotiations with the state. Rather, it is the 800-pound gorilla at the negotiating table. And taxpayers are too often left to its mercy.

Endnotes

[1] James Sherk, “How Collective Bargaining Affects Government Compensation and Total Spending,” (testimony before the Committee on Government Affairs, Nevada Assembly, April 7, 2015), http://www.heritage.org/research/testimony/2015/how-collective-bargaining-affects-government-compensation-and-total-spending.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ted Dabrowski and John Klingner, Illinois State Workers Highest Paid in Nation (Illinois Policy Institute, Spring 2016), https://www.illinoispolicy.org/reports/illinois-state-workers-highest-paid-in-nation/.

[4] Mailee Smith, AFSCME vs. the Private Sector: A Comprehensive Review of the Most Absurd Benefits in the AFSCME Collective Bargaining Agreement (Illinois Policy Institute, Summer 2016), https://www.illinoispolicy.org/reports/a-comprehensive-review-of-the-most-absurd-benefits-in-the-afscme-collective-bargaining-agreement/.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Dabrowski and Klingner, Illinois State Workers Highest Paid in Nation.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] AFSCME members’ salary data received pursuant to a FOIA request to the Illinois Department of Central Management Services; U.S. Census Bureau, 2014 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates.

[10] Smith, AFSCME vs. the Private Sector: A Comprehensive Review of the Most Absurd Benefits in the AFSCME Collective Bargaining Agreement.

[11] U.S. Department of Labor, Glossary, https://www.dol.gov/general/aboutdol/history/glossary.

[12] Smith, AFSCME vs. the Private Sector: A Comprehensive Review of the Most Absurd Benefits in the AFSCME Collective Bargaining Agreement.

[13] See Robert P. Hunter, Michigan Labor Law: What Every Citizen Should Know (Mackinac Center, August 1999), https://www.mackinac.org/S1999-05.

[14] Ibid.

[15] 29 U.S.C. § 158(8(c)).

[16] Celeste Purdie and Jim Rhollans, Union Communication Guidance: TIPS and FOE (Society for Human Resource Management, April 26, 2016).

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Daniel V. Johns, Promises, Promises: Rethinking the NLRB’s Distinction Between Employer and Union Promises During Representation Campaigns, 10 J. Bus. L. 433, 437 (2008), http://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1303&context=jbl.

[20] Ibid. at 438.

[21] Ibid. at 439.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Editorial Board, “The Chicago Teachers Union’s Vote Charade,” Chicago Tribune, September 21, 2016, http://www.chicagotribune.com/news/opinion/editorials/ct-chicago-teachers-union-strike-vote-edit-20160921-story.html.

[24] Chris Isidore and James O’Toole, “Hostess Brands Closing for Good,” November 16, 2012, http://money.cnn.com/2012/11/16/news/companies/hostess-closing/.

[25] See James Sherk, How Public-Sector Unions Differ from Their Private-Sector Counterparts, in “Sweeping the Shop Floor: A New Labor Model for America” (Evergreen Freedom Foundation, 2010).

[26] United Mine Workers of America, 125 years of struggle and glory (July 2015), http://umwa.org/video/video125-years-struggle-glory/.

[27] United Mine Workers of America (Dictionary of American History 2003), http://www.encyclopedia.com/topic/United_Mine_Workers_of_America.aspx.

[28] Moshe Marvit, “5 Myths About Labor Unions,” Chicago Tribune, September 2, 2016, http://www.chicagotribune.com/news/opinion/commentary/ct-labor-unions-dues-right-to-work-20160902-story.html.

[29] Smith, AFSCME vs. the Private Sector: A Comprehensive Review of the Most Absurd Benefits in the AFSCME Collective Bargaining Agreement.

[30] David Denholm, Are Labor Unions a Good Thing? And Can They Survive?, in “Sweeping the Shop Floor: A New Labor Model for America” (Evergreen Freedom Foundation, 2010).

[31] Franklin D. Roosevelt, “Letter on the Resolution of Federation of Federal Employees Against Strikes in Federal Service” (August 16, 1937), http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=15445.

[32] Government Unions 101: What Public-Sector Unions Won’t Tell You (Heritage Foundation, 2016), http://www.heritage.org/research/factsheets/2011/02/government-unions-101-what-public-sector-unions-wont-tell-you.

[33] Rachel Culbertson, Origins of the Industrial-Age Labor Model: History Shapes the Future in Labor Policies, in “Sweeping the Shop Floor: A New Labor Model for America” (Evergreen Freedom Foundation, 2010).

[34] Chris Edwards, Public-Sector Unions (Cato Institute, March 2010), http://object.cato.org/sites/cato.org/files/pubs/pdf/tbb_61.pdf.

[35] Ibid.

[36] For purposes of this report, the author specifically examined the Illinois Public Labor Relations Act because of its relevance to AFSCME.

[37] Sally J. Whiteside, Robert P. Vogt, and Sherryl R. Scott, Illinois Public Labor Relations Laws: A Commentary and Analysis, 60 Chi.-Kent L.Rev. 883, 884 (1984). See ibid. at 929 (“For the most part, the IPLRA tracks the language of the NLRA ….”).

[38] Whiteside, Vogt and Scott, Illinois Public Labor Relations Laws: A Commentary and Analysis, at 883, 884-885.

[39] Whiteside, Vogt and Scott, Illinois Public Labor Relations Laws: A Commentary and Analysis, at 883, 886.

[40] Whiteside, Vogt and Scott, Illinois Public Labor Relations Laws: A Commentary and Analysis, at 883, 897.

[41] The main focus is on a government-worker union’s use of threats to get its way – not necessarily on its ability to cripple a state or local government. Unions can put a damper on some day-to-day government activities, but not to the extent they threaten. Unions forecast doom and gloom to sway the public into siding with the union; but that doom and gloom typically amounts to smoke and mirrors. During a strike, a government can hire replacement workers to keep the state or locality operating. And under the IPLRA, public safety workers – such as police and firefighters – cannot strike. See 5 ILCS 315/14. Public safety should not be compromised when government workers go on strike. See also 5 ILCS 315/18 (allowing the employer to petition a court for an injunction against strike activity when there is a threat of clear and present danger to the health and safety of the public).

[42] See Sherk, How Public-Sector Unions Differ from Their Private-Sector Counterparts.

[43] All figures were computed by the Illinois Policy Institute from data obtained from the State Board of Elections.

[44] 30 ILCS 500/50-37.

[45] State of Illinois, Department of Central Management Services, and American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees, Case Nos. S-CB-16-017/S-CA-16-087, Administrative Law Judge’s Recommended Decision and Order (September 2, 2016) at 10, https://www.illinois.gov/ilrb/decisions/decisionorders/Documents/S-CB-16-017rdo.pdf.

[46] Ibid. at 12.

[47] Ibid. at 13.

[48] Ibid.

[49] David Giuliani and Chris Andriesen, The Anatomy of Influence: Government Unions in Illinois (Illinois Policy Institute, 2015), at 22.

[50] Ibid.

[51] Illinois Sunshine, https://www.illinoissunshine.org/committees/citizens-for-rauner-inc-25185/.

[52] See House Bill 580; Senate Bill 1229.

[53] See Bureau of Labor Statistics, Union Members – 2015, Table 3 (January 28, 2016), http://www.bls.gov/news.release/union2.t03.htm.

[54] See State: Union Membership, Coverage, Density, and Employment by State and Sector, 2015, http://www.unionstats.com.

[55] Agreement Between the State of Illinois and the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees Council 31 and AFL-CIO, Dated July 1, 2012, (the “Collective Bargaining Agreement” or “CBA”), Article V, Sec. 6; Article VI, Sec. 1.

[56] CBA, Article VI, Sec. 8.

[57] CBA, Article VI, Sec. 1.

[58] CBA, Article VI, Sec. 10.

[59] CBA, Article VI, Sec. 3.

[60] Rather than taking time off work without pay, an employee can utilize vacation days or personal days and thus still be paid while doing union work. CBA, Article VI, Sec. 3.

[61] CBA, Article XXIII, Sec. 10.

[62] CBA, Article XXIII, Sec. 22.

[63] CBA, Article XXIII, Sec. 22.

[64] CBA, Article VI, Sec. 7.

[65] CBA, Article VI, Sec. 2(a); CBA, Article VI, Sec. 4.

[66] CBA, Article V, Sec. 6(b). Long distance or toll calls by the union, at the expense of the state, are prohibited.

[67] CBA, Article VI, Sec. 5.

[68] A union member must sign a “dues checkoff,” which authorizes the state to deduct union dues directly from the employee’s paycheck. That amount is then remitted directly to the union. When a union member resigns membership and becomes a fair share payer, he revokes the authorization, or the “dues checkoff,” allowing the state to do so.

[69] CBA, Article VI, Sec. 5.

[70] CBA, Article VI, Sec. 2(b).

[71] CBA, Article I, Sec. 5.