Property-tax-for-pensions plan would pummel Illinois homeowners

By Orphe Divounguy, Bryce Hill, Joe Tabor

Property-tax-for-pensions plan would pummel Illinois homeowners

By Orphe Divounguy, Bryce Hill, Joe Tabor

The Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago released a report May 7 that claims to have found the best solution to paying off Illinois’ state pension debt, which researchers peg at anywhere from $130 billion to $250 billion.1,2

The proposed solution? Force Illinois homeowners, who already pay among the highest property taxes in the nation, to pay billions more each year through a statewide property tax. The typical Illinois household would pay an additional $1,948 in property taxes for the next 30 years under this proposal to pay for the state’s pension debt – a 44 percent increase.3

The report’s authors claim this plan is the best way to pay for the overpromising and underfunding of Illinois’ broken pension system, alleging that it is fair, efficient, transparent, certain and equitable. Unfortunately, the Chicago Fed economists are wrong on all counts.

Chicago Fed report claim: The statewide property tax would be efficient.

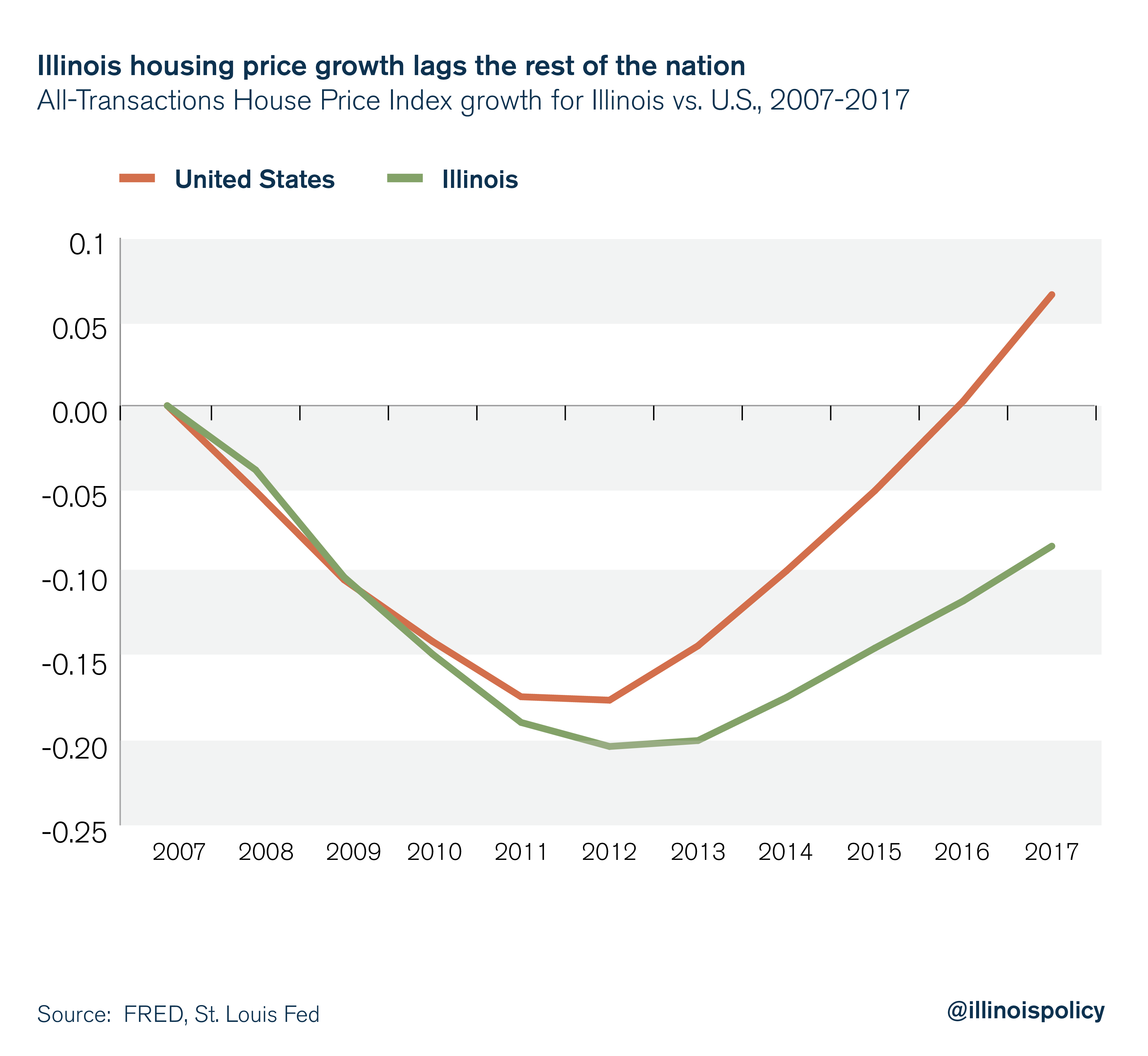

Illinois reality: The proposed tax would further slow Illinois’ housing market recovery. Illinois home prices are still nearly 10 percent below pre-recession levels,4 and pushing them down even further by saddling homes with even higher property taxes only erodes the life savings of many homeowners. Depressed home values could have negative spillover effects on the state’s fragile economic expansion.

Economist Frank Ramsey was a pioneer on optimal taxation. He suggested that if a social planner must raise a given amount of tax revenue, he must do so such that only commodities with inelastic demand are taxed. In other words, governments should try not to tax things that move.5 Since Ramsey’s work, economists have put forward that an efficient way to raise revenue – that is, maximizing revenues with the least reduction in the tax base – is to tax consumption goods and not investment goods.

Houses come close to fitting Ramsey’s “optimal taxation” mold, because they are not as responsive to taxation as other types of capital. They are illiquid assets and cannot be sold quickly for what would be considered the market price.6,7

This is why Chicago Fed economists proposed a statewide property tax to pay off Illinois’ pension liability. But in doing so, they illustrated the wide gap between Main Street and the economics profession.

Illinoisans are already overtaxed. The Illinois housing market still has not recovered from the last recession, and it is irresponsible to propose policies that would ultimately slow down the housing market recovery without additional reforms.

The time it takes Illinois homeowners to sell their home was still nearly double the national average in February 2018: 71 days8 compared to a national average of 37 days.9 A housing market recovery means that the time it takes to sell a home in Illinois has been declining and prices have been slowly increasing again since 2012.10 However, the Chicago Fed economists’ plan could reverse that trend.

Employment growth and housing price growth are strongly correlated. Recent economic research highlights links between regional labor and housing markets. In their article “The Recent Evolution of Local U.S. Labor Markets,”11 authors Maximiliano Dvorkin and Hannah Shell examined the recession and recovery by reviewing the correlation between county-level unemployment rates and changes in housing prices. U.S. counties with larger decreases in housing prices experienced larger increases in the unemployment rate.

Why did unemployment rise so severely in some areas but stay low in others? One explanation may be related to the elasticity of the housing supply. Gascon, Arias and Rapach (2016)12 argue that areas with an inelastic housing supply (i.e., the supply does not respond much to changes in house prices) are more vulnerable to recessions and experience worse downturns than areas with a more elastic supply. An inelastic housing supply can lead to larger house price drops and declines in net worth during downturns, leading to larger declines in local consumption spending that further depress the local economy.

This means declining house prices could have negative spillover effects on the rest of Illinois’ economy.

A report prepared for the Illinois Commission on Government Forecasting and Accountability offers a grim portrait of Illinois’ current economic condition, and a bleak forecast of its future.13 Illinois does not measure up to neighboring states or to the rest of the country on most gauges of economic performance. Illinois employment is increasing more slowly than U.S. averages; and the labor force has fallen to its lowest point in more than 10 years. Illinois was 42nd in the nation for employment growth in 2017, finishing dead last among neighboring states.14

Chicago Fed report claim: A statewide property tax is fair and equitable

Illinois reality: There is nothing fair about asking taxpayers to pay billions more every year in taxes without doing anything to address the root cause of the problem – overpromised pension benefits. Thousands of homeowners are already at risk of losing their homes because they cannot afford their current property taxes, and the additional property tax will disproportionately harm low-income and minority households.

Property taxes are particularly harmful to impoverished and elderly Illinoisans on fixed incomes, because they’re not reflective of an individual’s ability to pay.

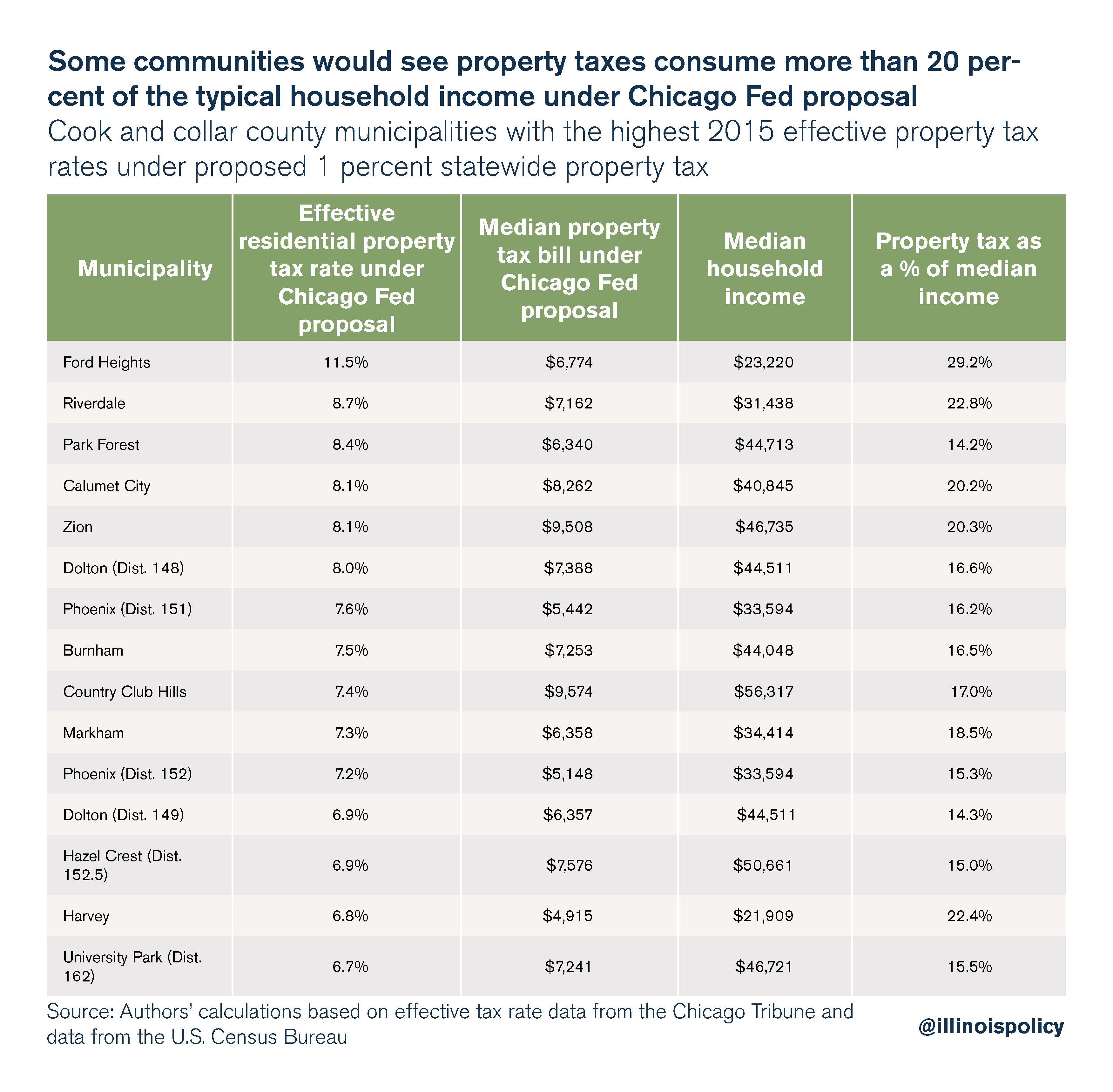

Further, minority and low-income communities already suffered the largest loss of wealth during the last recession. The housing crash meant that households with a greater concentration of wealth in their homes – young families and minorities – fared worse than other groups.15 This new tax would prevent minorities and low-income families from closing the wealth gap since most of their wealth is in their homes.16 Data from the Chicago Tribune show that among Cook and the collar counties, 14 of the 15 communities with the highest effective property tax rates are predominately African-American.

The tax hike would cost the median household in Calumet City, a predominately African-American community, an additional $1,056 in property taxes.17 This is particularly painful to these households as the community’s median household income is only $40,845 (more than $18,300 lower than the state’s median household income).18

Similarly, the median household in University Park, a predominately African-American village, would see its tax bill increase by $1,127 while its median household income is $12,475 lower than the state median.19 The median household in Harvey would see its tax bill increase by $756,20 meaning the typical household would pay more than 22 percent of its income in property taxes.21 Riverdale, a primarily African-American area in Cook County, would see its tax bill increase by over $861, meaning that the typical household would see 23 percent of its income eaten up property taxes.22

To call the Chicago Fed economists’ statewide property tax fair is disingenuous. The plan would disproportionately affect the poor as the tax is determined by home values, which are disassociated from individuals’ ability to pay the tax.

In addition, any new property tax would rely on local assessment systems, which in many cases have failed Illinoisans. There have been numerous reports on how Cook County’s system in particular favors the wealthy over the poor.23 Wealthier homeowners have the time and money to appeal their property assessments and reduce their tax bills.

Thousands of Illinoisans are already struggling to pay their property taxes. As of 2017 there were over 50,000 instances of unpaid property taxes in Cook County alone, adding up to over $180 million in taxes owed to the various taxing districts in the county.24 More Chicago-area homeowners are underwater on their mortgages than homeowners in any of the other 10 largest U.S. cities.25

Homeowners in these areas can’t afford to pay more in property taxes. Low-income and minority communities are already seeing higher property taxes and diminished services to pay for pensions.

Chicago Fed report claim: The payment amounts and duration of the tax would be known in advance.

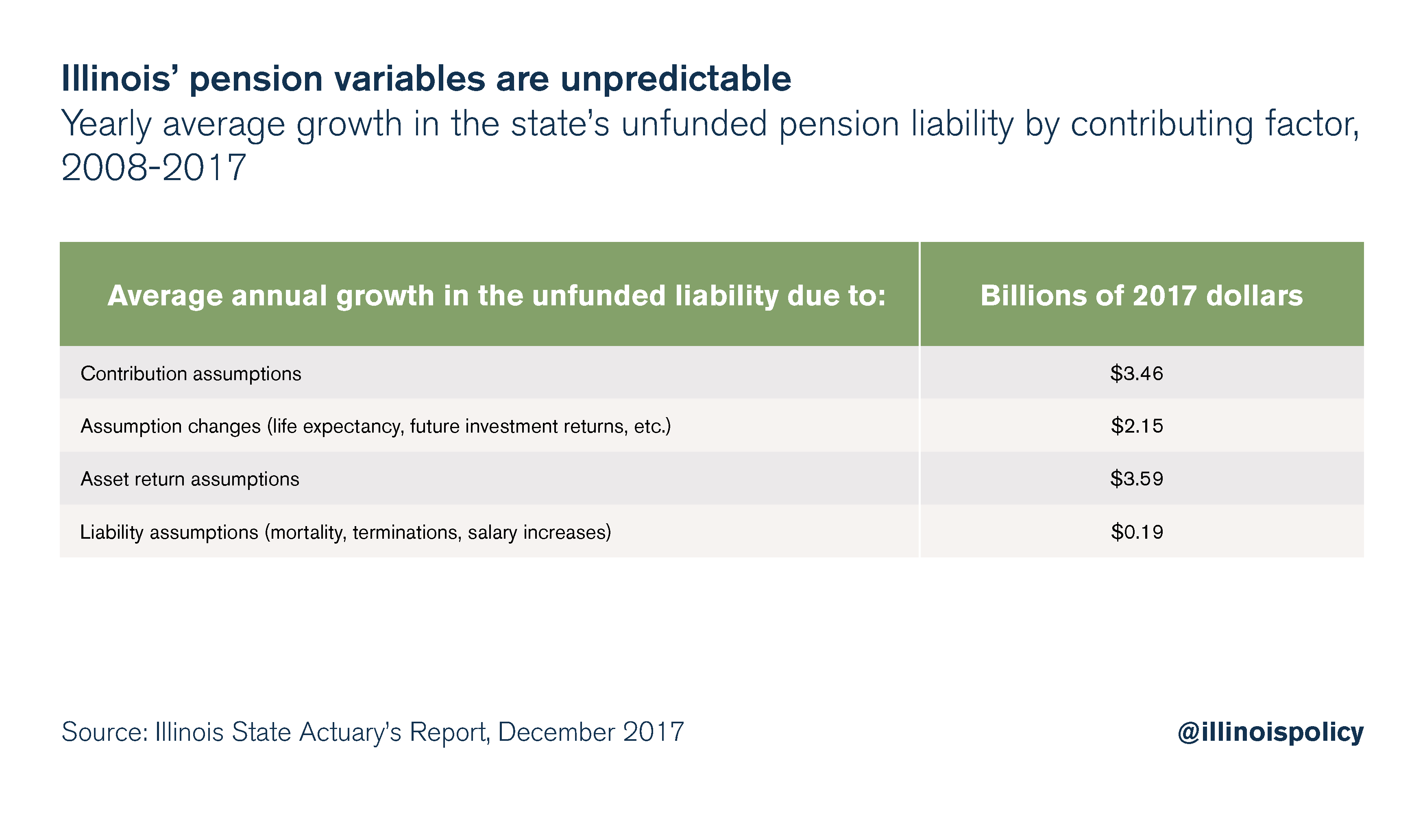

Illinois reality: The current pension liability relies on assumptions about investment returns and mortality rates that are difficult to predict. The rate of return gained by the pension fund can fluctuate greatly, and if the fund underperforms, taxpayers will have to contribute even more money.

Defined-benefit pension plans entail a great deal of uncertainty, which is one of the reasons many states have moved to defined-contribution, 401(k)-style plans. This is also why the Chicago Fed authors’ assumptions regarding the size of the deficit should be taken with a grain of salt. A case in point: While the Chicago Fed paper takes the overall pension liability to be $130 billion, Moody’s Investors Service pegs that number at $250 billion.

Illinois’ current pension liability is the result of not only current beneficiaries, but assumptions about how many future beneficiaries there will be, how long they will live and the rate of return the pension fund investments will generate. In the past decade, the unfunded liability of the state’s five major pension systems has been revised upward by an average of $9.4 billion each year, due to faulty assumptions that the system relies on.26

But faulty assumptions aren’t even the main reason this plan fails to provide certainty to property taxpayers. The biggest sources of uncertainty are Illinois lawmakers.

In 2011, politicians proposed a “temporary” income tax hike that would go toward paying Illinois’ backlog of bills. But after the state raised $31 billion in additional revenue, taxpayers were still left with billions of dollars in unpaid bills.27 Lawmakers saw the increased revenue as simply another opportunity to spend even more.

Two years after this temporary tax hike expired, lawmakers hit Illinoisans with another tax hike28 – all to accommodate the spending habits they had grown used to. And this time, the tax hike was permanent.

It will be the same with a statewide property tax. The Chicago Fed economists do not give Springfield enough credit for politicians’ ability to find new and creative uses for residents’ tax dollars. Illinoisans can bet politicians won’t give up that revenue if and when the time comes.

Conclusion

The statewide property tax proposal illustrates a disconnect between policymakers and the gravity of what Illinoisans are experiencing. It would squeeze already overburdened taxpayers for billions more each year with no end in sight to solve the state’s pension crisis. It would also condemn many homeowners to lose their homes or guarantee that their homes will never again be worth as much as they paid for them. Ultimately, any plan claiming to correct the problem without curbing the growth in pension benefits will fail to solve Illinois’ pension crisis.

Endnotes

- Commission on Government Forecasting and Accountability, Illinois State Retirement Systems Financial Condition as of June 30, 2017 (March 2018), http://cgfa.ilga.gov/Upload/FinConditionILStateRetirementSysMar2018.pdf.

- Ted Dabrowki and John Klingner, “Illinois owes over $250 billion in pension debt,” Illinois Policy Institute, June 1, 2017, https://www.illinoispolicy.org/moodys-downgrades-illinois-to-1-notch-above-junk-warns-state-pension-liabilities-top-250b/.

- U.S. Census Bureau, “American FactFinder”.

- Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, “All-transactions House Price Index for Illinois,” February 27, 2018, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/USSTHPI.

- Frank P. Ramsey, “A Contribution to the Theory of Taxation,” 37.145 The Economic Journal 47-61 (1927).

- J. Krainer “A theory of liquidity in residential real estate markets,” 49 Journal of urban Economics, 32-53 (2001).

- J. Krainer, “Falling house prices and rising time on the market,” FRBSF Economic Letter.

- “Illinois home prices climb higher in February; sales shift lower,” Illinois Realtors, 2018, https://www.illinoisrealtors.org/blog/illinois-home-prices-climb-higher-february-sales-shift-lower/.

- “Existing Home Sales Climb 11 Percent in March,” National Association of Realtors, April 23, 2018, https://www.nar.realtor/newsroom/existing-home-sales-climb-11-percent-in-march.

- Illinois Realtors, “Annual Report on the Illinois Housing Market,” Illinois Realtors, 2017, https://www.illinoisrealtors.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/IAR-Illinois_ANN_2017.pdf.

- Maximiliano Dvorkin and Hannah Shell, “The Recent Evolution of U.S. Local Labor Markets,” Economic Synopses no. 15 (2016).

- Maria A. Arias, Charles S. Gascon, and David E. Rapach, “Metro business cycles,” 94 Journal of Urban Economics 90-108 (2016).

- Moody’s Analytics/Economic & Consumer Credit Analystics, State of Illinois Economic Forecast (February 2018), http://cgfa.ilga.gov/Upload/2018MoodysEconomyILForecast.pdf.

- Bryce Hill, “Illinois Dead Last among Neighboring States for Jobs Growth in 2017,” Illinois Policy Institute, March 25, 2018, https://www.illinoispolicy.org/illinois-last-among-neighbors-42nd-in-the-nation-for-jobs-growth-in-2017/.

- Edward N. Wolff, Household Wealth Trends in the United States, 1962 to 2016: Has Middle Class Wealth Recovered?, No. w24085m National Bureau of Economic Research (2017).

- Wolff, Household Wealth Trends in the United States; William R. Emmons, “Is homeownership bad for wealth accumulation?” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, December 7, 2017, https://www.stlouisfed.org/publications/housing-market-perspectives/issue-7-december-2017/homeownership-bad-for-wealth-accumulation.

- Authors’ calculations based on property tax rate data from the Chicago Tribune and median home value data from U.S. Census Bureau “American FactFinder”.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Christopher Berry, “Estimating Property Tax Shifting Due to Regressive Assessments: An Analysis of Chicago, 2011-2015,” University of Chicago, March 2018, https://harris.uchicago.edu/files/inline-files/Estimating%20Property%20Tax%20Shifting%20Due%20to%20Regressive%20Assessments.pdf; Jason Grotto and Sandhya Kamhampati, “How the Cook County Assessor failed Taxpayers,” ProPublica, December 7, 2017, https://features.propublica.org/the-tax-divide/cook-county-commercial-and-industrial-property-tax-assessments/.

- “Cook County Property Tax Sale List,” Bridget Gainer, Cook County Commissioner – 10th District, http://www.bridgetgainer.com/tax-sale-properties.

- Amy Korte, “More Chicago-area homeowners drowning in mortgage debt than any other major city.” Illinois Policy Institute. February 9, 2018. https://www.illinoispolicy.org/more-chicago-area-homeowners-drowning-in-mortgage-debt-than-in-any-other-major-city/.

- Office of the Auditor General, State Actuary’s Report the Actuarial Assumptions and Valuations of the State-Funded Retirement Systems, December 2017, https://www.auditor.illinois.gov/Audit-Reports/Performance-Special-Multi/State-Actuary-Reports/2017-State-Actuary-Rpt-Full.pdf.

- Benjamin VanMetre, “Illinois’ $31 billion tax hike: Where did the money go?” Illinois Policy Institute, March 21, 2014, https://www.illinoispolicy.org/policy-points/illinois-31-6-billion-tax-hike-where-did-the-money-go/.

- Austin Berg, “Illinois lawmakers pass permanent income tax hike, override Rauner’s veto,” Illinois Policy Institute, July 6, 2017, https://www.illinoispolicy.org/illinois-lawmakers-pass-permanent-income-tax-hike-override-rauners-veto/.