A worker’s right to choose

Hundreds of thousands of Illinois workers are forced to pay union dues to keep their jobs. But close by, worker freedom reigns.

Rejection

Ever since he was 10 years old, Steve Vaughn knew he wanted to be an electrician. That’s what his father did at ComEd while raising Steve and his three brothers in Antioch, Illinois.

Decades later, Steve has followed in his father’s footsteps, working as a low-voltage electrician and senior installer at a northern Illinois cabling company. He works hard to support his wife and three children.

Steve has worked in the building trades since he was 15, except for a four-year hiatus during which he served in the Marine Corps. He left for boot camp one week after graduating from high school.

When he returned home from the service, Steve figured he’d try union membership, again following in his father’s footsteps. The elder Vaughn occasionally complained about his union but was a member until his retirement.

Steve drove down to a Waukegan, Illinois, union hall to test his skills.

He says he did well, scoring in the top 15 percent of about 800 applicants. His experience and love for the work shined through.

A few weeks later, Steve got a call from the union.

“They said they really liked me,” Steve said. “But they had to meet their quota for minority and female workers.”

He was denied membership and would have to go through the rigorous testing process again if he wanted another shot.

“It wasn’t a race or gender thing with me,” Steve said. “But I knew then that I didn’t want to spend the rest of my career playing these sorts of games. I’m good at what I do.

“I’m not against unions, … but a lot of them aren’t fair to workers.”

Fairness

Members of Illinois unions such as the one that passed up Steve’s talents are often forced to pay dues or fees to keep getting work. But that’s not the case for workers elsewhere in the region.

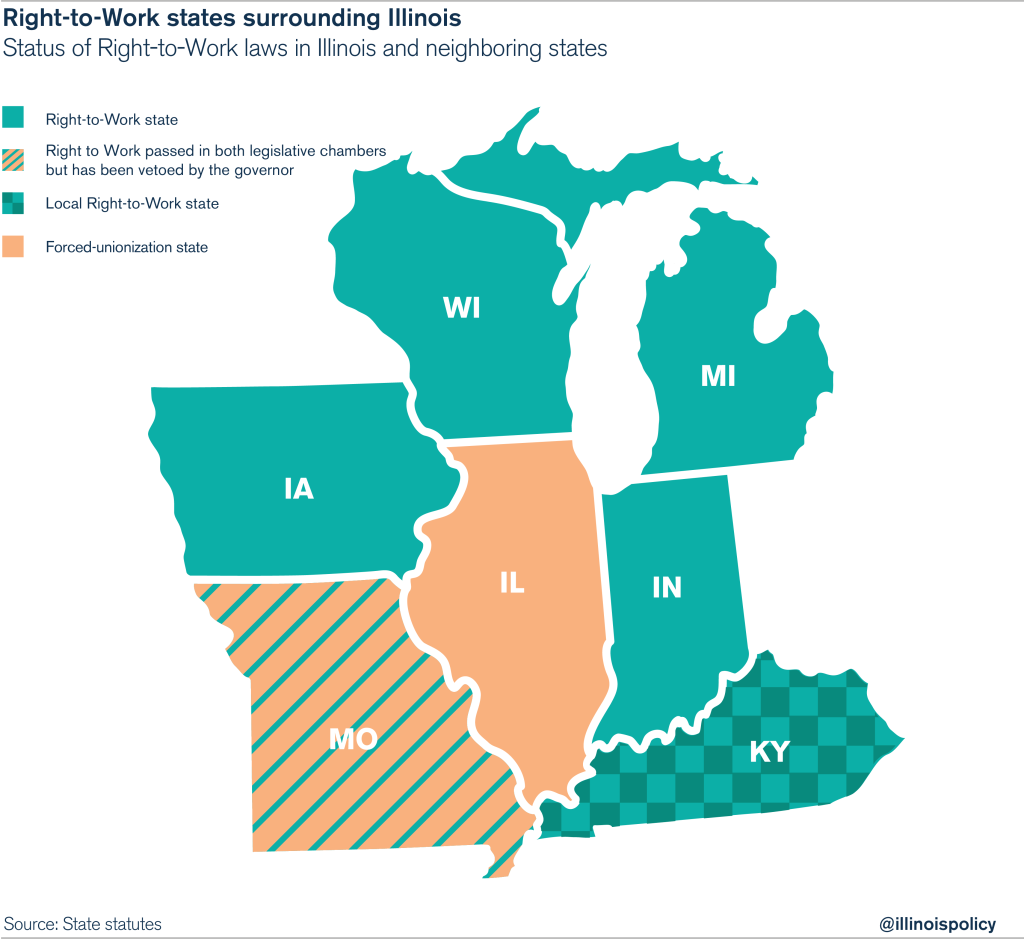

In fact, the three states to enact Right-to-Work laws most recently are Illinois neighbors: Indiana (2012), Michigan (2013) and Wisconsin (2015). Missouri would have followed Wisconsin’s lead in 2015 if not for its governor’s veto of Right-to-Work legislation.

A Right-to-Work law means workers can choose whether to pay dues or fees to a union. Twenty-five states give workers this right. But in forced-unionization states such as Illinois, workers can be fired for refusing to pay union dues or fees.

Despite union executives who imply otherwise, Right to Work does not affect collective bargaining or any other labor law. Workers and unions are free to negotiate wages, hours, benefits and anything else for which they could negotiate before the enactment of a Right-to-Work law. The difference is that unions can’t compel workers to pay them.

Steve says that’s not anti-union or anti-worker. It’s just fair.

His frustration with Illinois’ forced-unionization climate comes from what he saw his friends go through during the Great Recession.

“When the construction business went bust in 2008, a lot of guys were out of work,” he said.

“All the union reps were still making their salaries. But the guys actually doing the work [were] sitting at home on unemployment waiting for work to pick up again. That’s not fair – there’s no work for them, but they still have to pay their dues? These guys are trying to feed their families.”

Results

Government data show that workers in Right-to-Work states are seeing faster wage and jobs growth than their peers in forced-unionization states such as Illinois.

Neighboring Michigan and Indiana have both seen faster wage growth and jobs growth than Illinois since passing Right-to-Work laws.

Illinois’ lack of worker freedom has it sticking out like a sore thumb for prospective investors. Illinois Department of Commerce and Economic Opportunity Director Jim Schultz says more than 1,100 companies have blacklisted the state due to its lack of a Right-to-Work law.

And those who call Right to Work “anti-union” are ignoring evidence to the contrary.

Indiana jobs growth has been so robust that the state has more union members now than when it passed Right to Work in 2012. Indiana added 50,000 dues-paying union members in 2014, tied for the largest gain in the country.

And it’s not just Indiana. Over the last decade, forced-unionization states have seen a 9 percent decline in union membership, while Right-to-Work states have seen net growth in union membership.

Another benefit of Right to Work is greater union accountability. That’s tough to measure, but the current secretary–treasurer of the United Auto Workers, Gary Casteel, may have said it best:

This is something I’ve never understood, that people think [R]ight to [W]ork hurts unions. … To me, it helps them. You don’t have to belong if you don’t want to. So if I go to an organizing drive, I can tell workers, ‘If you don’t like this arrangement, you don’t have to belong.’ Versus, ‘If we get 50 percent of you, then you all have to belong, whether you like to or not.’ I don’t even like the way that sounds, because it’s a voluntary system, and if you don’t think the system’s earning its keep, then you don’t have to pay.

Steve looked at this from the other side.

“What’s in it for the union rep to do any better?” he asked.

“If I go to work and I don’t do my job, I’ll get in trouble and I’ll get fired. Is the same thing going to happen to a union rep? Probably not. They’re protected. You [should] have to care about the people you’re working for.”

Empowerment

Although a statewide Right-to-Work law is all but impossible in Illinois, given Democratic supermajorities in the Illinois General Assembly, a model solution exists just across the state border, in Kentucky.

Since January 2015, Kentucky counties have been enacting local Right-to-Work laws to kickstart the state’s manufacturing sector. The results are impressive.

The nation’s first Right-to-Work county was Warren County. Within a few months of passing local Right to Work, Warren County received 27 inquiries about prospective company projects, representing nearly 3,700 new jobs and $324 million in new investment.

With a workforce of only 62,000 (by comparison, Illinois’ Kendall County has a workforce of 64,000), those are major results.

The “home rule” provisions in state law that allowed Kentucky counties to act on this issue are at least as strong for Illinois municipalities. This means struggling communities in the Land of Lincoln need not wait for a resolution to the gridlock in Springfield. They can choose to take matters of worker freedom into their own hands.

Just ask the residents of Lincolnshire, Illinois.

On Dec. 14, Lincolnshire’s village board voted to become the first Right-to-Work municipality in the Land of Lincoln. The results remain to be seen, but mitigating the effects of the Midwest’s worst jobs climate and seemingly endless layoffs in the manufacturing sector may require this sort of historic action from local leaders across Illinois.

“Let’s see if they have the courage,” Steve said.