Consolidating school districts could cut family’s tax bill by $1,030

House Bill 7 would create a process to review and recommend consolidating school district administration, with the goal of cutting bureaucracy so the money goes to classrooms or back to taxpayers.

West Chicago gave the Zentners good schools in a quiet community when they decided to buy a home and raise their two children.

During the next 18 years, it also gave them nearly triple their original property tax bill. They support 15 taxing bodies, nine pension systems and two school districts.

“We have watched our property taxes go from $2,800 when we first bought the home in 2002 to roughly $8,200 according to our reassessment last spring,” Megan Zentner said.

The schools take 70% of their property taxes, but their two schools are not the only schools in town.

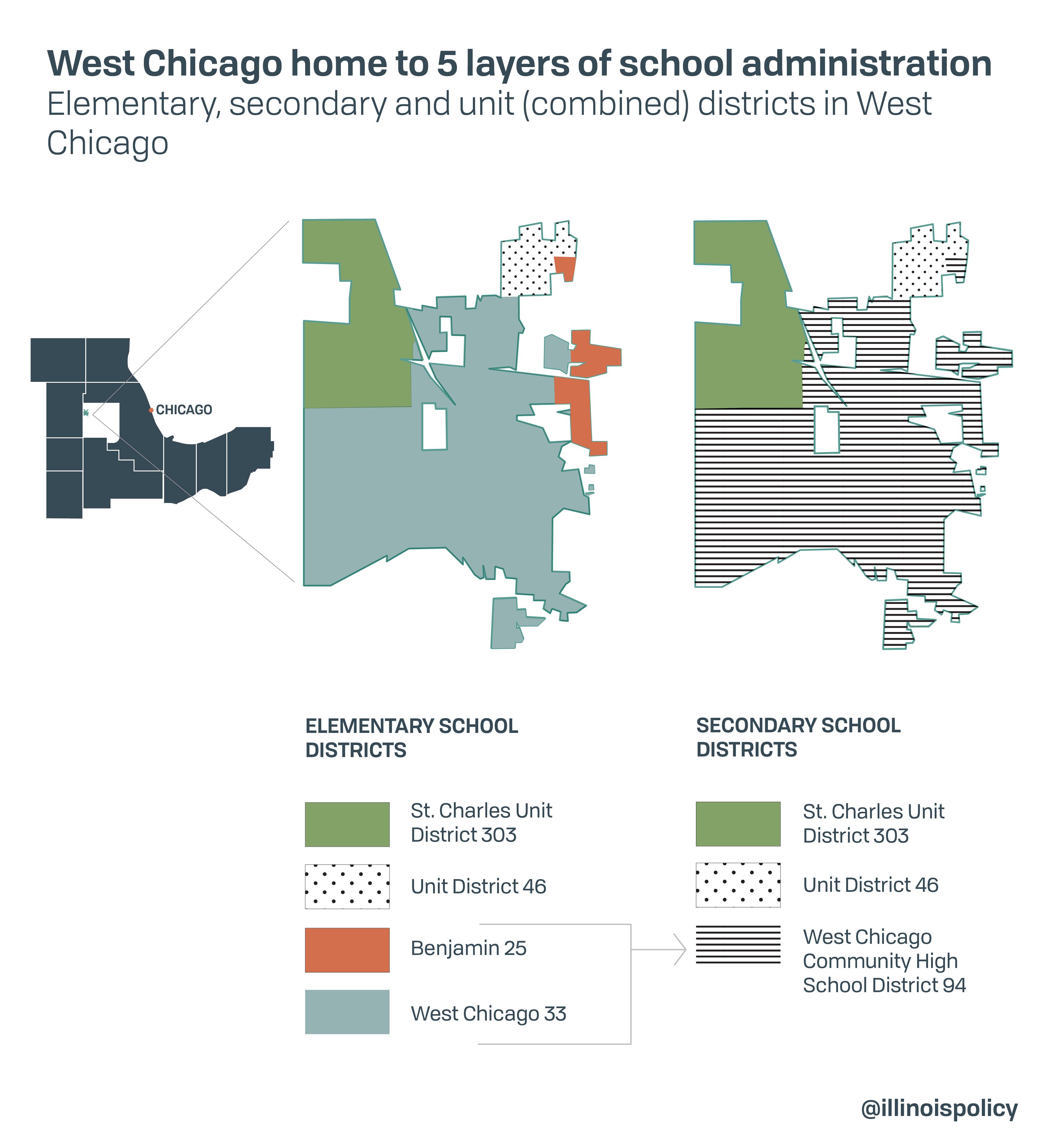

“We live in a small town of around 27,000 people, so I am boggled by the fact that we are split up among five school districts: 25, 33, U-46, 94, and District 303,” she said.

It’s inefficient to have so many separate school districts, each with its own set of administrators and overhead, in a city of that size, she said.

“Furthermore, dividing the town among so many school districts also divides the community.”

The Zentners could be paying $1,030 less on their property tax bills just by consolidating the two separate school districts they help support, according to an analysis by the Illinois Policy Institute. No schools would go away but were administration of the separate grade school district and high school district consolidated there would be efficiencies that could help improve classroom instruction or give taxpayers a break.

That is the aim of House Bill 7, the Classrooms First Act, sponsored by state Rep. Rita Mayfield, D-Waukegan. It would create the School District Efficiency Commission, tasked with recommending specific district consolidations with a goal of cutting the number by 25% across Illinois. Voters in each district would need to agree before any local districts merged.

Illinois has 852 school districts and nearly half serve only one or two schools – such as West Chicago Community High School District 94. All that excess bureaucracy leads to high costs: Illinois spent $1.19 billion on district-level administration in 2018, but California is able to serve three times as many students for over one-third less.

Illinois spends $598 per student on district-level administration, more than two and a half times the national average of $237. If Illinois reduced its general administrative spending to the national average per student, it would save $716.6 million in bureaucratic costs.

That amount is over double the $350 million state leaders promised to boost school spending each year when they revamped the school funding formula in 2017. That promise was broken for the current school year, with Gov. J.B. Pritzker keeping school spending flat. He’s proposed doing the same again in his upcoming budget.

Illinois’ student and teacher populations each dropped 2% between 2014 and 2018, but administration grew 1.5% during that time. Administration isn’t cheap: 204 district superintendents and assistant superintendents in Illinois made $200,000 or more in 2020.

Besides the tax savings, consolidating districts improves academics and leads to better student test scores. A 2018 studyfound increasing the size of a district to 1,000 students improves the average SAT score by 48 points, with another 14 points added by increasing to 2,000 students.

While the Zentners pay most of their property taxes toward the two school districts, they are also paying to support pension funds for DuPage County, its health department, forest preserve and the township, in addition to their school districts. Technically, payments for the Teacher’s Retirement System are paid in by the state and the teachers themselves, however in Zentner’s districts the school board covers the teachers’ portions – meaning they pay for these pensions on both ends.

The state’s $144 billion pension debt is not the only crisis facing taxpayers: there is another $63 billion in local government pension debt that causes property taxes to rise each year. West Chicago’s 2018 report shows the city collected $4.6 million dollars in revenue from property taxes and paid $3.5 million, or 70%, into their police and municipal pension funds.

“It is definitely a situation where we are spending a whole lot of money, but we are not really seeing any return in the way our property is valued compared to the other houses in town in different school districts,” Zentner said.

Paying more for school district administration that doesn’t improve student learning and paying for pension costs that compound by 3% a year regardless of inflation are driving up property taxes. Those taxes are driving out Illinoisans.

HB 7 would be one solution. Amending the Illinois Constitution to allow future, unearned public pension benefits to be controlled would be another.