Budget Solutions 2018: Balancing the state budget without tax hikes

By Ted Dabrowski, Craig Lesner, John Klingner, Michael Lucci

Download Report

Budget Solutions 2018: Balancing the state budget without tax hikes

By Ted Dabrowski, Craig Lesner, John Klingner, Michael Lucci

Download Report

If there’s one message many Illinois politicians and civic groups want taxpayers to hear this budget season, it’s that there’s no fixing Illinois’ fiscal and economic mess without a multibillion-dollar tax hike.

Tax-hike proponents also want residents to believe the Illinois General Assembly has already passed all the structural reforms it can, and the only thing left to do now is to hike taxes by $7 billion to $9 billion – and that will fix everything.

But that narrative is false. The General Assembly has done nothing to stop Illinois’ downward spiral.

The Illinois Policy Institute’s 2018 Budget Solutions offers a plan that reverses the state’s failed course. The plan fills Illinois’ $7.1 billion budget hole, balances the state budget without tax hikes, provides tax relief to struggling homeowners through a comprehensive property tax reform package, and implements pension reforms that comply with the Illinois Constitution and will begin to end the pension crisis.

It also implements many of the spending and economic reforms Illinoisans instinctively know are needed to create more jobs, generate higher pay and provide a better living environment, including right-sizing state worker benefits, implementing savings for Medicaid and making higher education more affordable for students by reducing administrative costs.

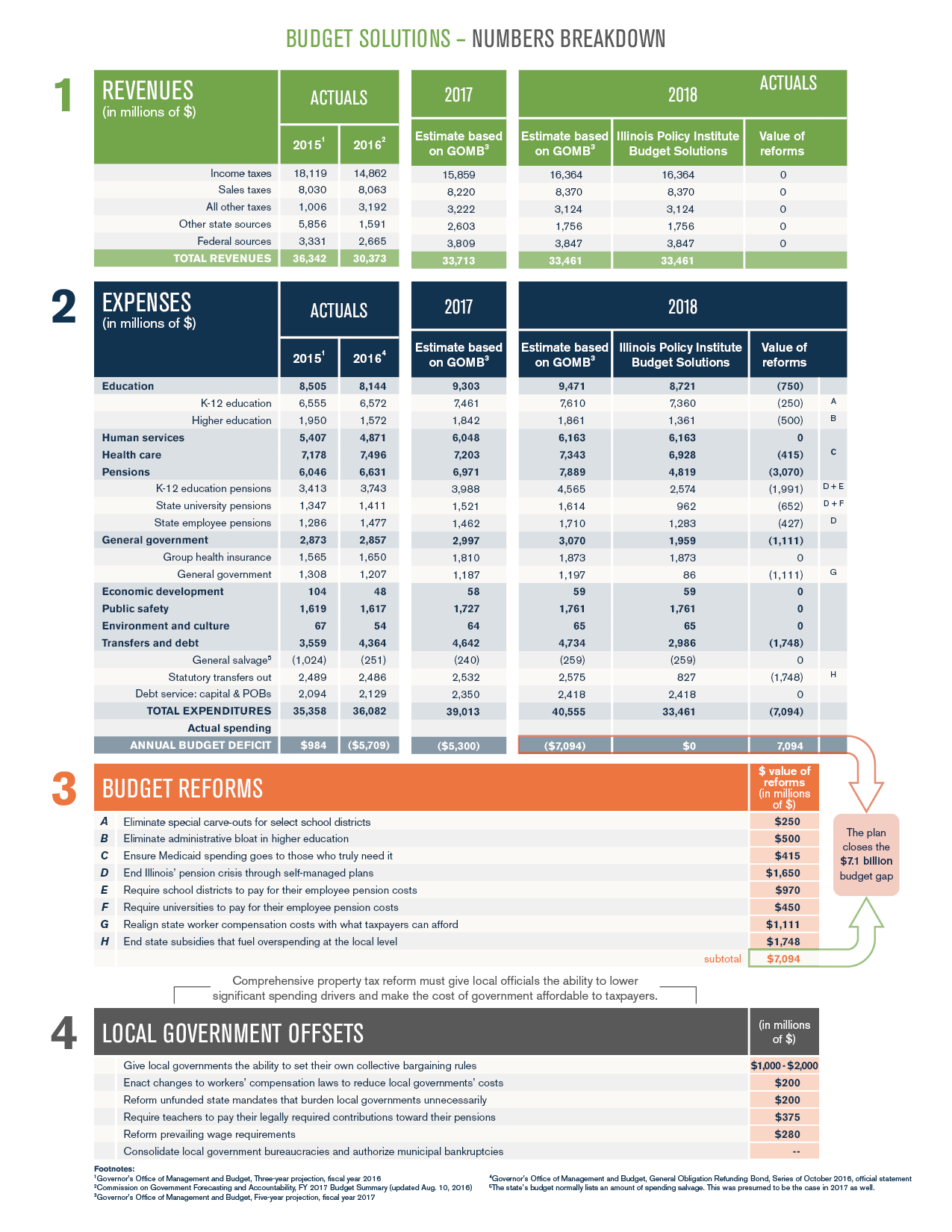

The Institute’s plan is as follows:

A. Enact comprehensive property tax reform – $3.4 billion in savings

Illinoisans are forced to pay the nation’s highest property taxes to prop up Illinois’ 7,000 units of local government – the most in the nation – and the bureaucracies that run them.

In some Illinois communities, residents pay 5 percent or more of the value of their home to property taxes. For many, that’s more than they pay toward their mortgage each year. In those places – such as in Chicago’s Southland area – homeowners will pay twice for their homes over a 20-year period: once to purchase their home and a second time in the equivalent amount of property taxes.

But property taxes aren’t the only thing fueling excessive local government spending. Billions more in state subsidies help drive local spending on employee perks and other expenses such as the seventh highest workers’ compensation costs in the nation. Many of these costs result from state mandates that only increase costs for taxpayers.

Illinois taxpayers deserve relief. That’s why Illinois needs comprehensive property tax reform that includes not just a five-year property tax freeze, but reforms to the state subsidies and mandates that increase local costs.

Step 1: 5-year property tax freeze

- Freeze the property tax levy of every local government in Illinois for five years, including home rule and non-home rule local governments.

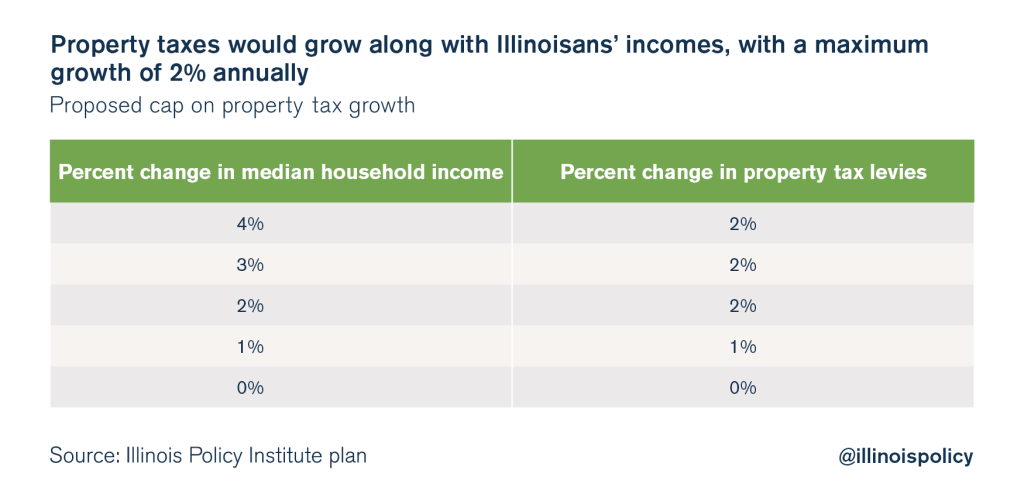

- Base the annual increase in local government levies not on inflation, but on Illinoisans’ ability to pay higher taxes. After the five-year freeze, property tax levies will grow based on the annual change in Illinois’ statewide median household income, with a maximum of 2 percent and a minimum of zero.

- Require a referendum when governments wish to raise other local taxes or fees. To pass, the referendum must be approved by two-thirds of local voters.

Step 2: Curb wasteful spending habits by eliminating local government subsidies

Billions in state subsidies allow local officials to funnel money where it’s most politically expedient – all without having to answer to local taxpayers. Those billions prop up unnecessary perks and expenses including salary spikes, pension sweeteners and workers’ compensation costs that would otherwise be unaffordable. Subsidies ripe for elimination include:

- Revenue-sharing agreements that fuel excessive local spending, such as the Local Government Distributive Fund – for counties and cities with populations above 5,000 – and the Downstate Transit Fund. (Savings: $1.75 billion)

- State pension subsidies that allow districts and universities to dole out higher pay, end-of-career salary hikes and pensionable perks. Going forward, local school districts and universities should be responsible for paying the annual (normal) cost of pensions. (Savings: higher education: $450 million; K-12: $970 million)

- Special carve-outs in the state’s education funding formula that grant subsidies to a select few school districts affected by local property tax caps and special economic zones. (Savings: $250 million)

Step 3: Eliminate costly state mandates and give back spending control to local governments

Freezing property taxes and ending state subsidies won’t be enough to fix Illinoisans’ tax burdens. Local officials must be given greater control over their own budgets so they can reduce the burden on local taxpayers and reform how local government is delivered.

- Reform costly state mandates imposed on local governments such as prevailing wage requirements and collective bargaining rules. Ease the process for government consolidation and other cost-saving measures. (Local government savings: $2 billion-$3 billion)

B. End Illinois’ pension crisis through self-managed plans – 2018 pension contribution $1.65 billion less than baseline

Illinois’ pension math simply doesn’t work. It doesn’t work for pensioners, who are worried about their collapsing retirement security. It doesn’t work for younger government workers, who are forced to pay into a pension system that may never pay them benefits. It doesn’t work for taxpayers, who pay more and more each year toward increasingly insolvent pension funds. And it doesn’t work for Illinois’ most vulnerable, who have seen vital services cut to make room for growing pension costs.

The status quo cannot continue. Illinois must follow the lead of the private sector and over a dozen other states, such as Michigan and Oklahoma, and move away from its broken defined-benefit pension system.

State worker retirements can be put on a path to financial security by passing a holistic retirement reform plan that complies with the Illinois Constitution and creates a new self managed plan for state workers.

The Institute’s comprehensive retirement reform plan:

- Respects the decisions of the Illinois Supreme Court by making changes that do not diminish or impair pension benefits.

- Enrolls all new workers in a new hybrid self-managed retirement plan, or SMP, based on the State Universities Retirement System’s own SMP. The hybrid plan contains two key elements: an SMP and an optional Social Security-like benefit.

- Gives all current workers the option to enroll in the SMP. Retirees, and current workers who do not opt in, will be unaffected by the plan.

The plan will result in a number of valuable benefits for state workers, retirees and taxpayers, including:

- Providing increasingly stable and predictable costs for the state budget going forward.

- Significantly reducing the growth in accrued liabilities.

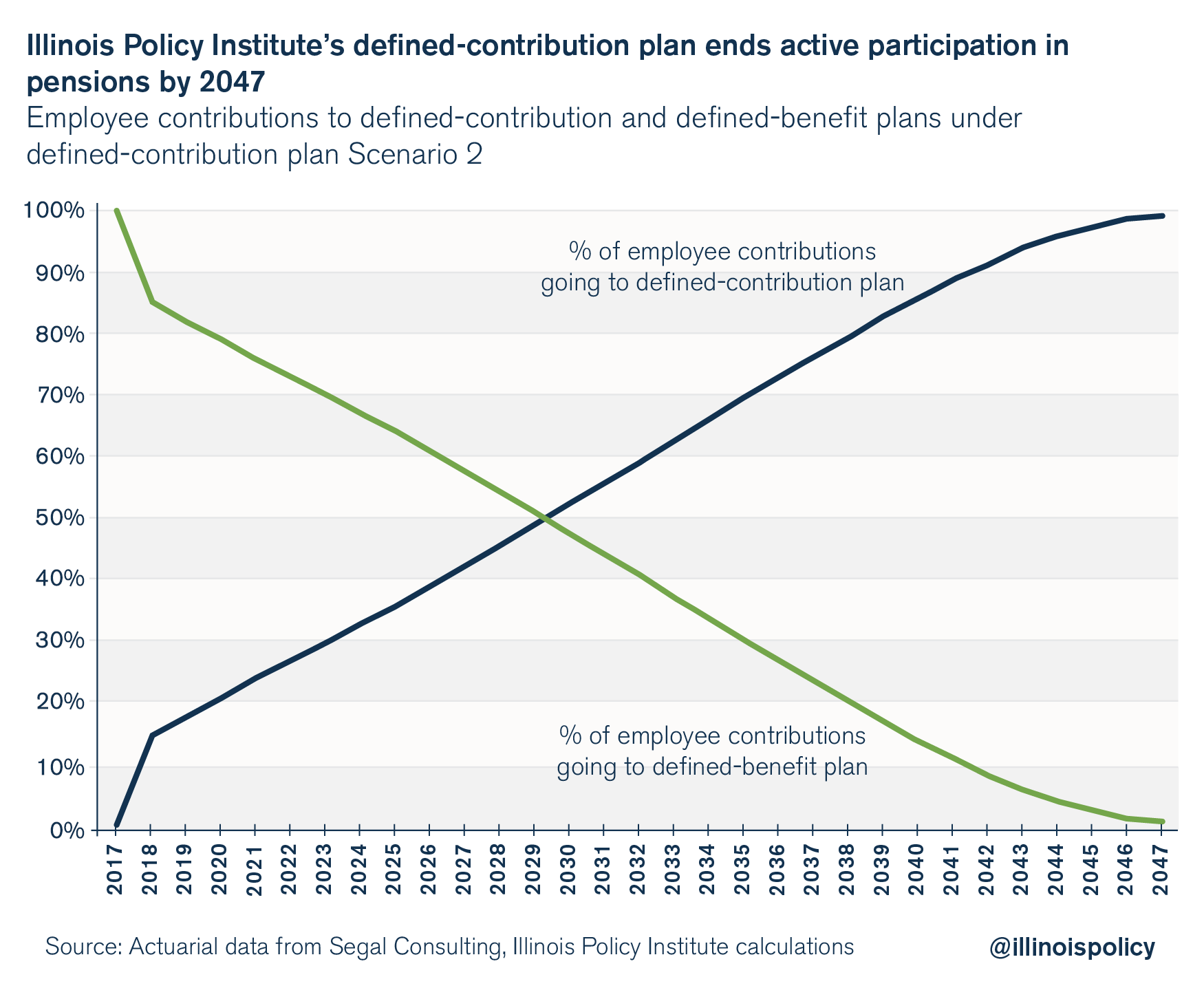

- Ending Illinois’ reliance on its broken pension system by moving virtually every active worker into an SMP by 2047.

- Eliminating the unfair Tier 2 benefit plan for new workers and allowing existing Tier 2 members to opt in to the new SMP.

- Sending a strong message to investor and credit agency groups that Illinois is finally tackling its pension crisis.

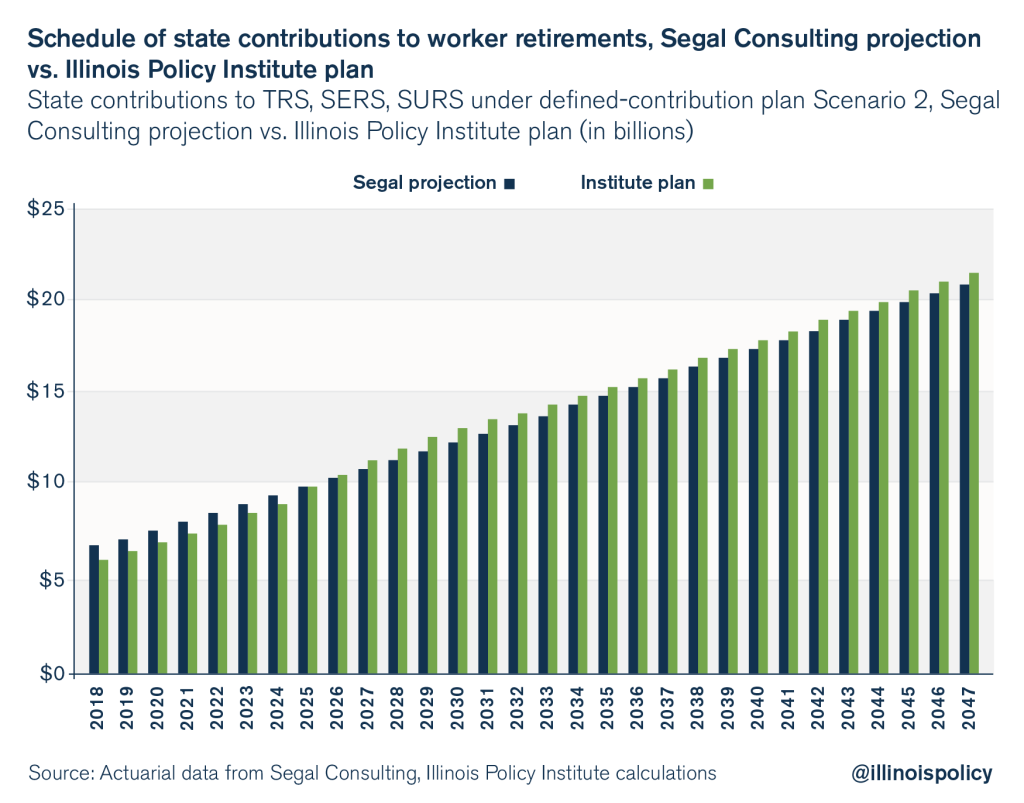

- Phases in the costs of any pension funds’ actuarial changes over a five-year period. This will reduce the required $800 million increase in state contributions by nearly $650 million in 2018.

- Creates a new contribution schedule with a 2018 payment that is $1 billion less than baseline contributions. That will protect overburdened Illinoisans from tax hikes and allow the state to prioritize funding for social services.

To achieve the above benefits – including ending unfair Tier 2 pensions – the state must invest the equivalent of $7 billion to $18 billion in today’s dollars over the next 30 years.

This is the only pension plan that protects worker benefits under the Illinois Constitution, protects funding for social services, avoids harming Illinoisans with another tax hike, shifts normal costs to local governments to discourage benefit spiking, begins an end to the broken pension system, eliminates the unfair Tier 2 benefit structure, and provides real retirement security to state workers.

C. Align AFSCME costs with what taxpayers can afford – $1.1 billion in savings

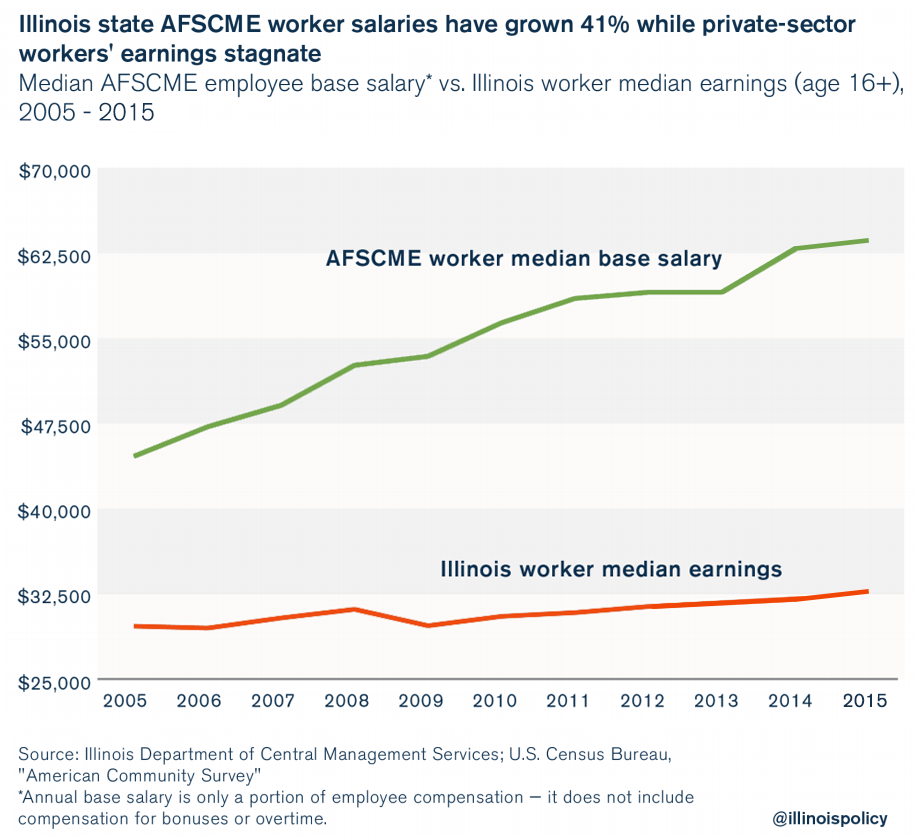

Illinois’ middle class and blue-collar workers are struggling amid one of the worst economic recoveries in the nation.

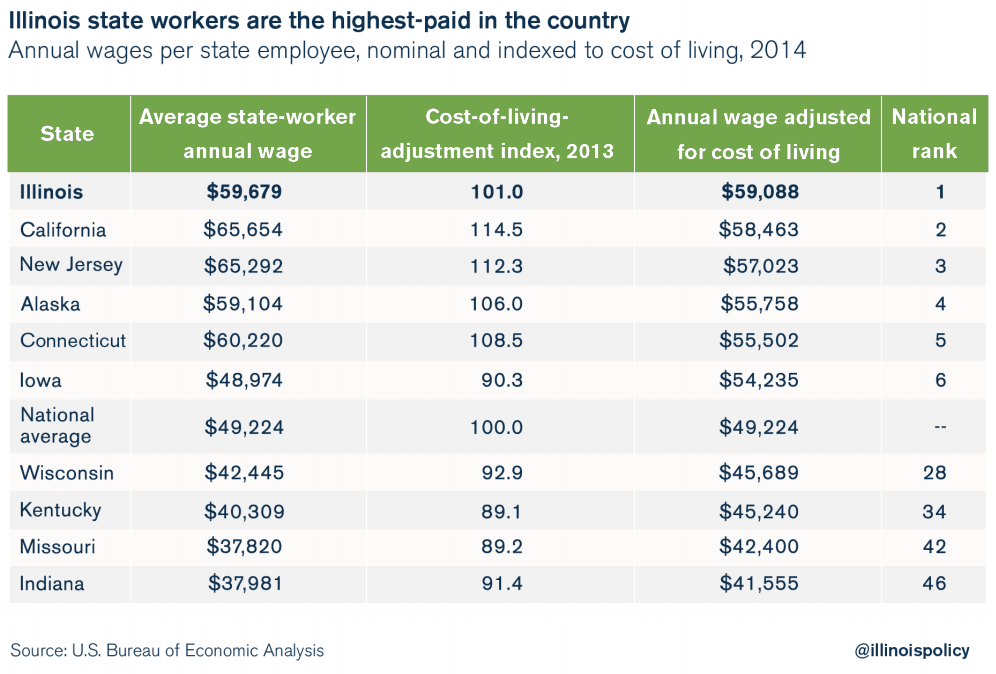

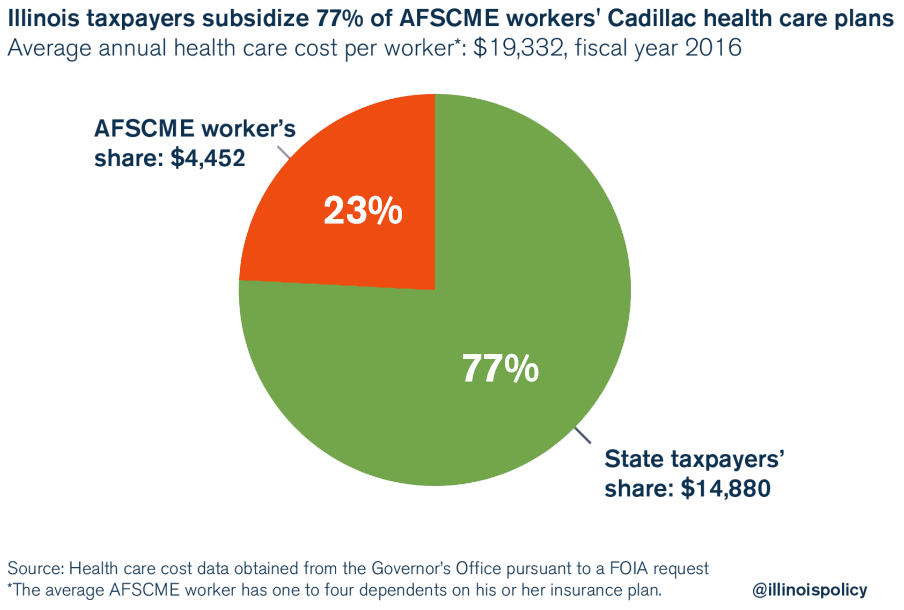

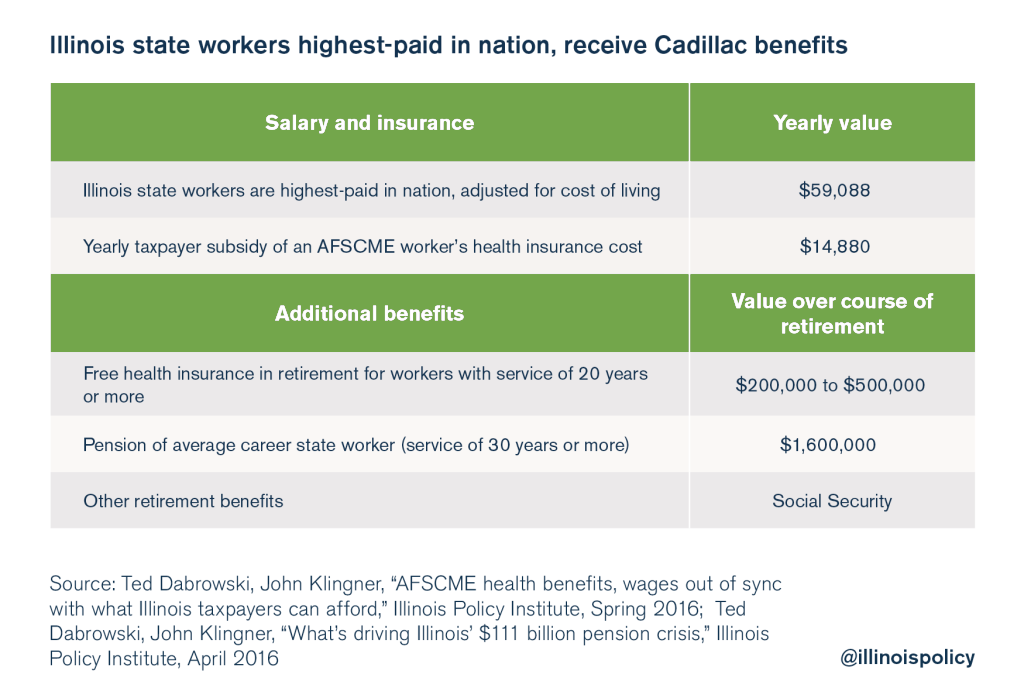

That pain will only get worse if the costs of state government continue to increase. Illinois taxpayers already have to pay for state workers’ generous benefits, including the highest salaries in the nation, heavily subsidized health care, free retiree health care for most workers and overly generous pension benefits.

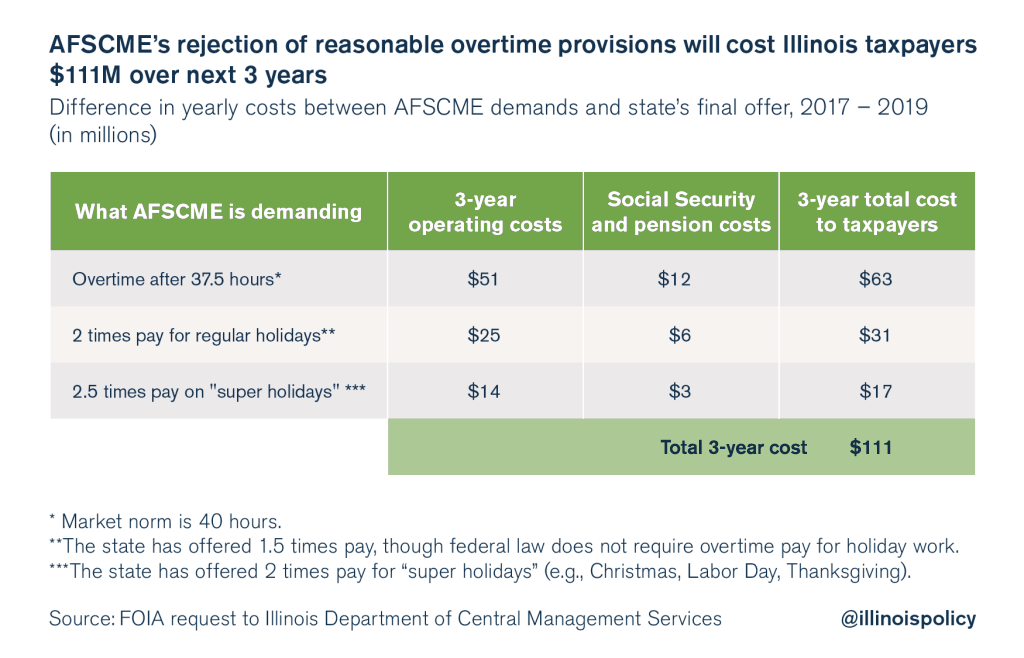

If the state is able to implement its last, best contract offer to the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees, which represents 35,000 state workers, it will save taxpayers hundreds of millions in government overtime and health care costs, among other expenses.

In addition, the state can further reform the costs of employee compensation by reducing state payroll by $500 million, or a little more than 10 percent, in 2018.

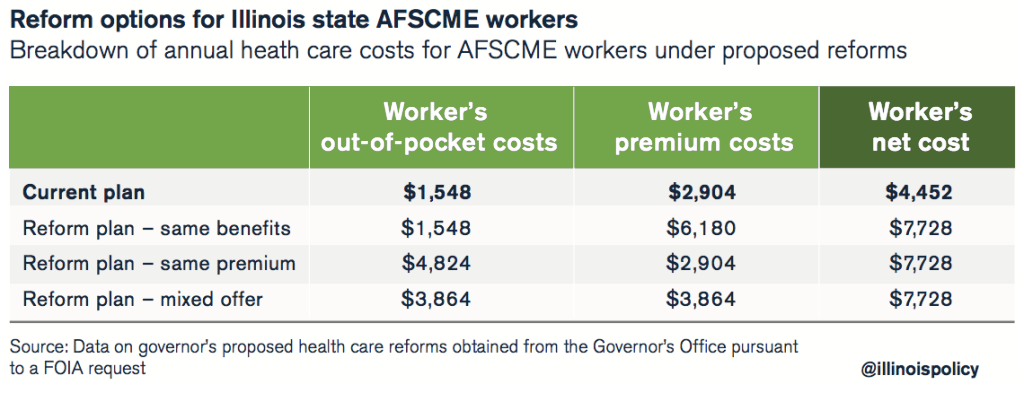

- Implement the state’s contract offer which, among other savings, reins in state workers’ excessive overtime benefits and enacts reasonable health care reform that still provides affordable, flexible and fair health care options for state workers. (Savings: $600 million)

- Reduce 2018 state payroll by $500 million. (State savings: $500 million)

D. Streamline Medicaid spending – $415 million in savings

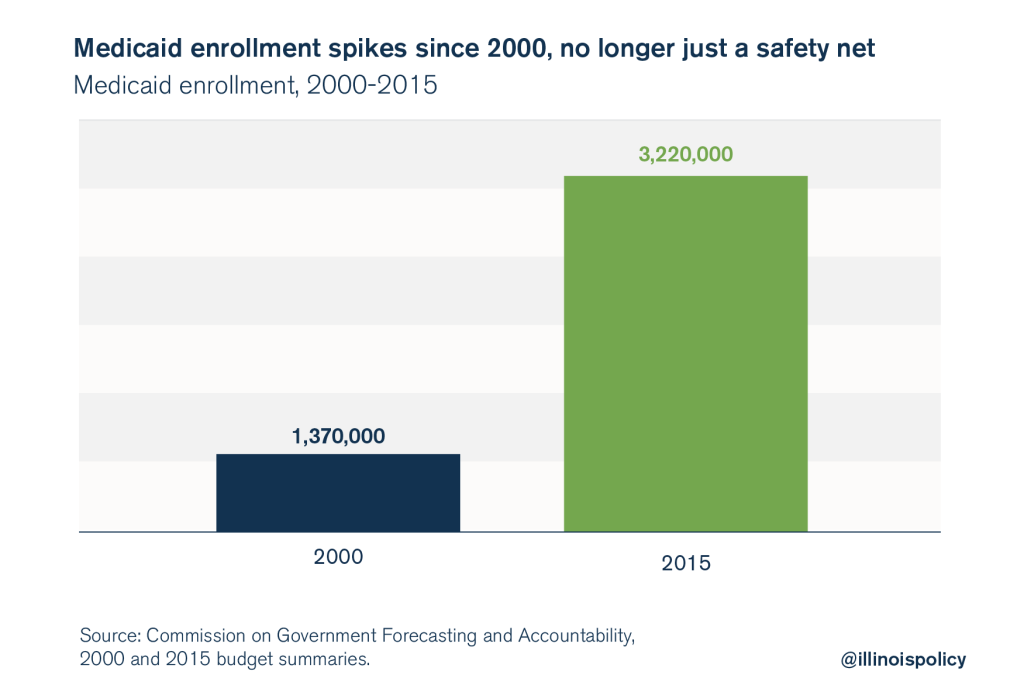

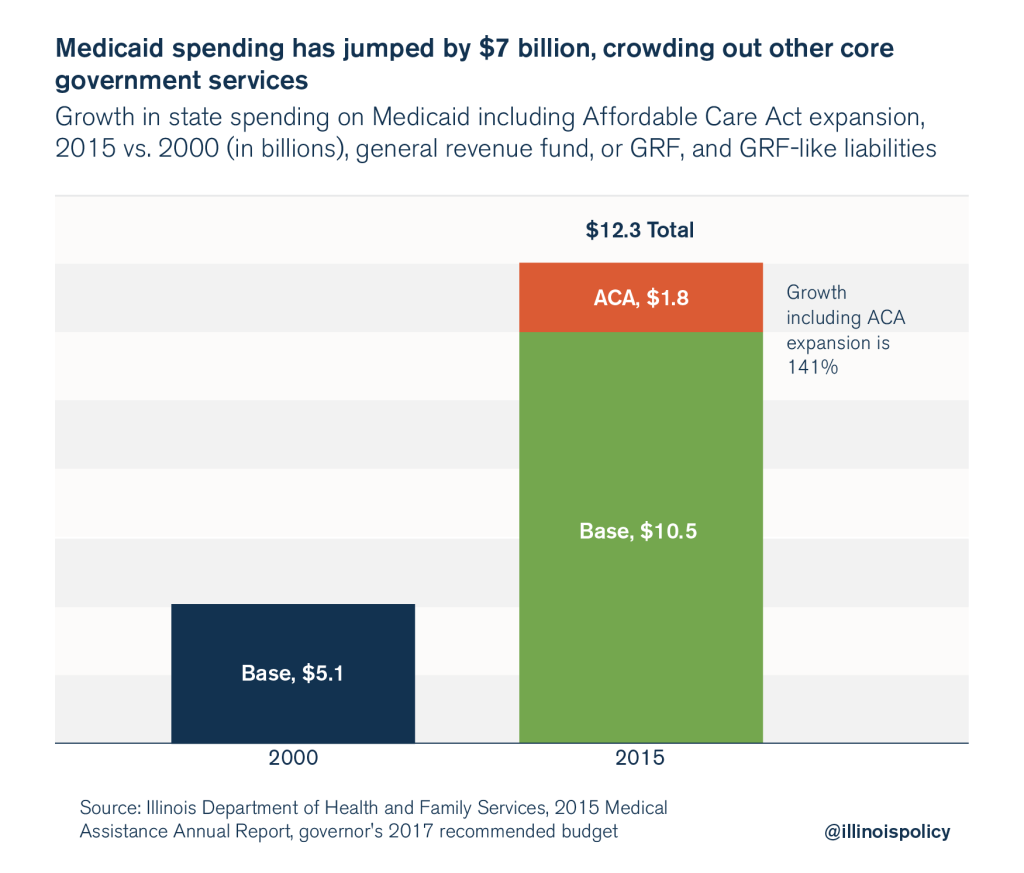

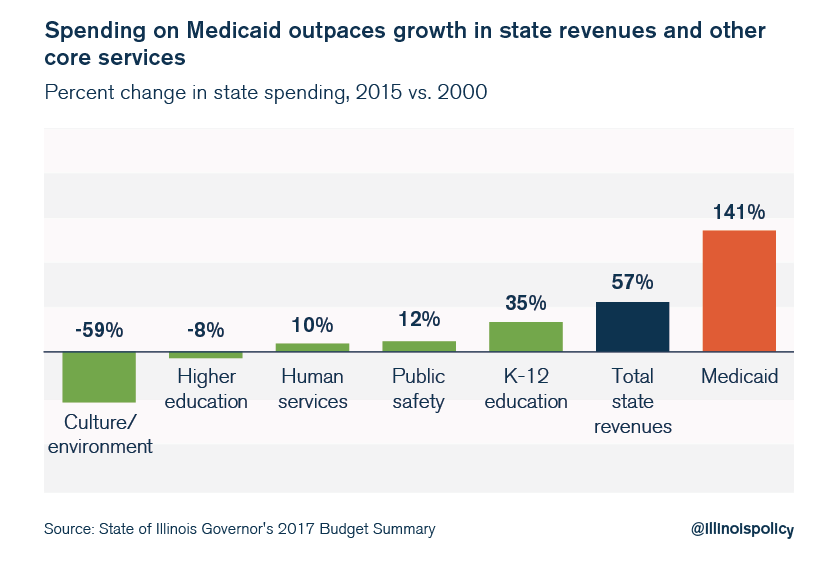

For many Illinoisans, Medicaid means poor access to health care. Much of that failure can be blamed on a Medicaid enrollment that has ballooned to 3.2 million Illinoisans, crowding out resources for the very people Medicaid was intended to protect. That’s a sorry outcome for a state that spends 25 percent of its general fund budget on health care, largely on Medicaid. The state can pursue improvements that will lower the burden that Medicaid imposes on Illinoisans. Those reforms include:

- Applying more frequent eligibility checks to ensure resources are spent only on those eligible for services. (State savings: $135 million)

- Lowering drug costs so more Medicaid patients can get the medicine they need. (State savings: $70 million)

-

Leveraging volume purchases and competitive bidding to lower medical equipment costs. (State savings: $55 million)

-

Repealing ObamaCare’s Medicaid expansion to ensure patients who need the most help have quicker access to doctors. (State savings: $125 million)

-

Utilizing ambulatory surgical centers that specialize in outpatient procedures to reduce costs and shorten patient wait times. (State savings: $30 million)

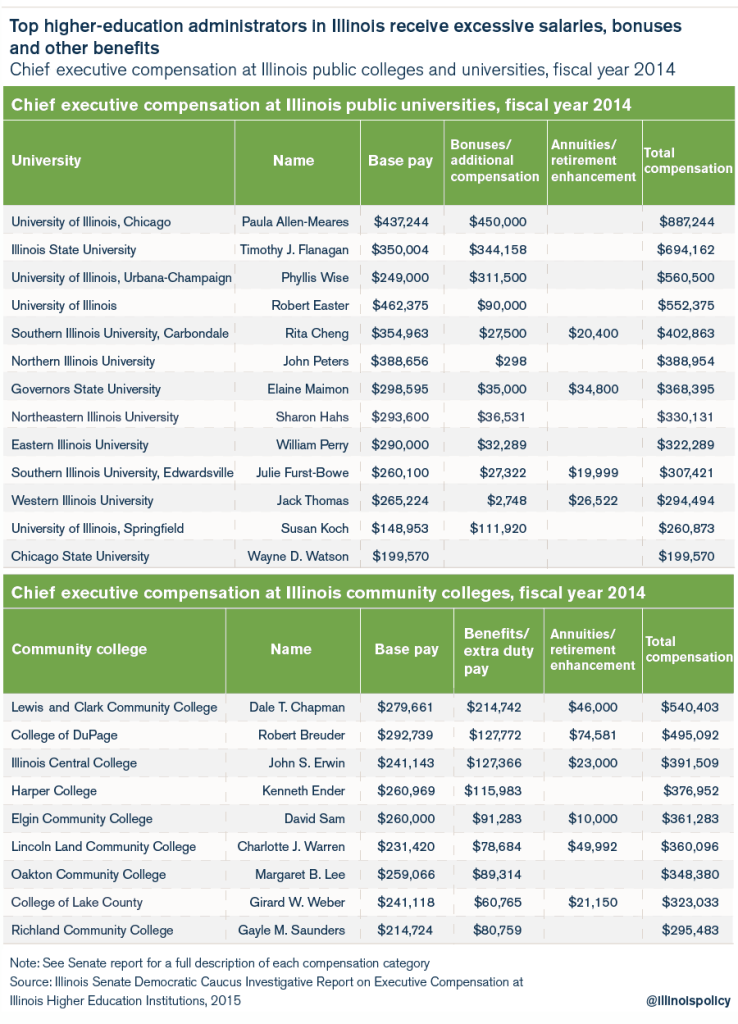

E. Higher education: Prioritize students over administrators – $500 million in savings

Illinois’ college and university officials blame the state’s budget crisis for the mess in higher education.

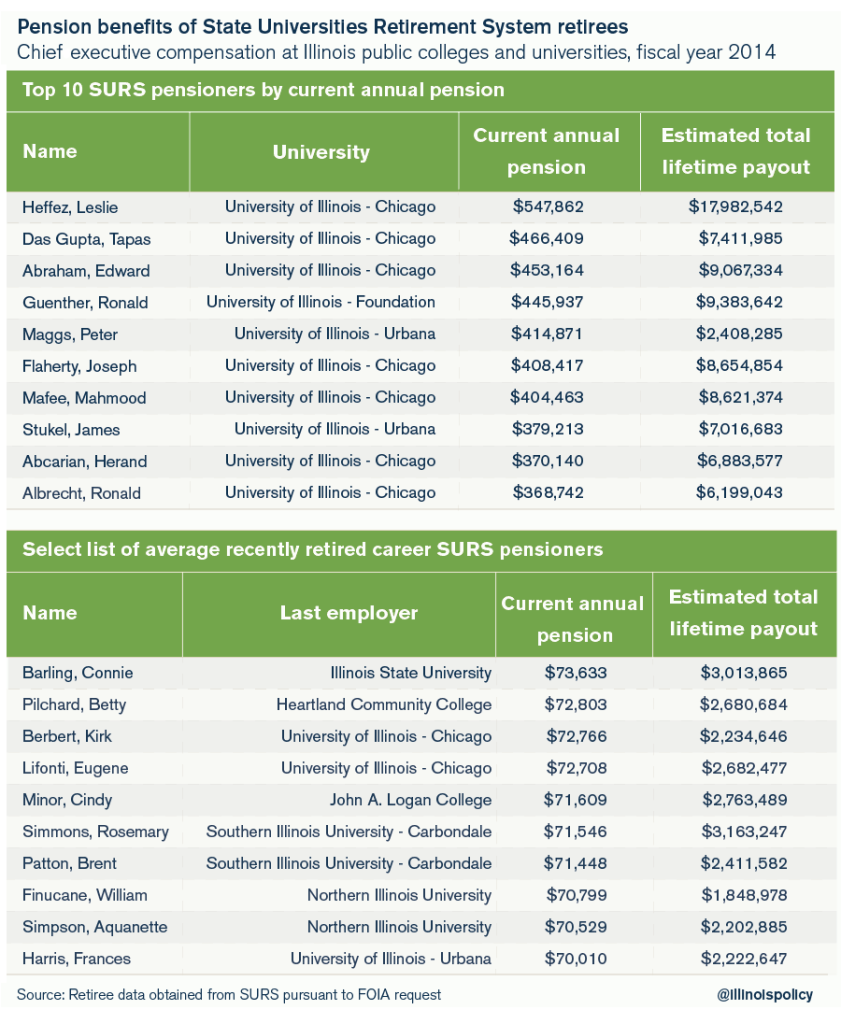

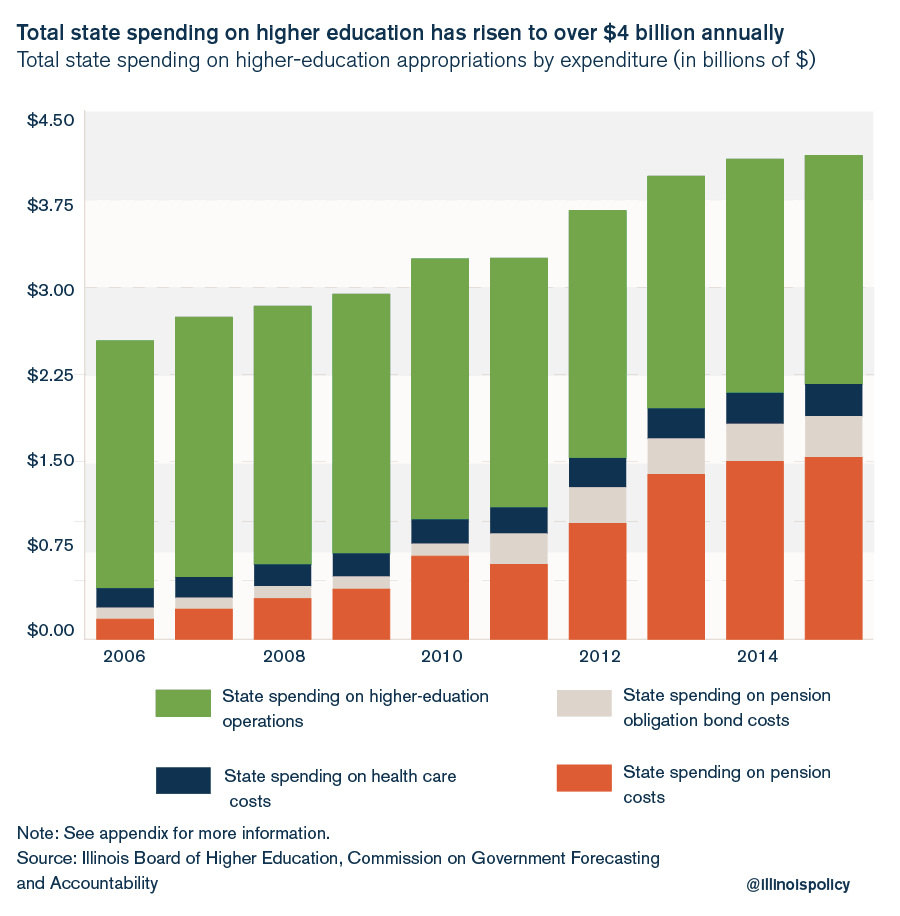

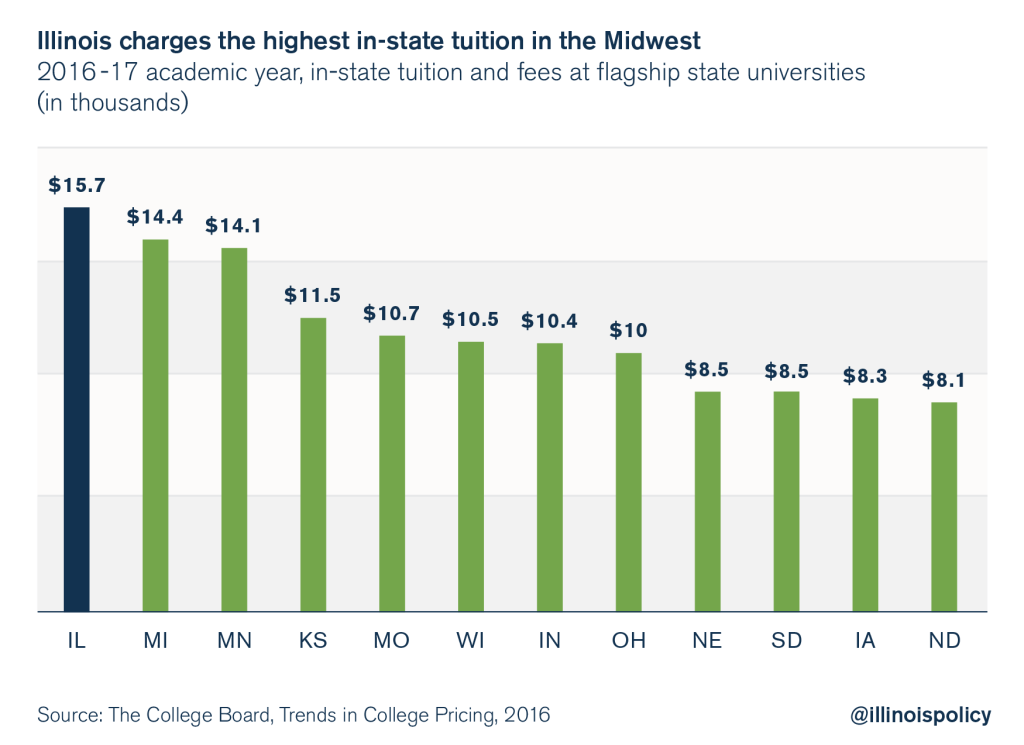

But budget gridlock isn’t why Illinois’ higher education system is facing financial troubles. Instead, it’s the growing number of administrators and their ballooning costs that make college unaffordable for too many of Illinois’ students, especially those with limited means. Illinois spends more money on administrative and retirement costs than on university operations. In fact, more than 50 percent of Illinois’ $4.1 billion budget for state universities is spent on retirement costs.

Colleges and universities must enact reforms to operational spending, reduce the cost of salaries, and eliminate administrative bloat. If they don’t, the destructive cycle of hiking tuition while relying increasingly on state subsidies will continue, making higher education less and less affordable for Illinois’ students.

In the meantime, the state cannot continue to subsidize Illinois universities’ bloated administrations and benefits. The Institute’s plan would lower state appropriations to colleges and universities by the equivalent of a little more than 10 percent of projected payroll costs in 2018.

- Reduce state appropriations to higher education by $500 million in 2018. (State savings: $500 million)

Introduction

Billions in tax hikes on struggling Illinoisans and businesses is not the solution to the state’s budget crisis.

The real solution is transforming how Illinois government operates and how it spends taxpayer dollars. Illinoisans know that because they experience the broken nature of Illinois government every day.

Seniors who want to stay in their homes after retirement are still being pushed out by the nation’s highest property taxes, in large part because they are forced to pay for too many units of local government and the bloated bureaucracies that run them.

Middle-class and blue-collar workers continue to see their manufacturing jobs disappear, a result of the state’s job-killing economic policies.

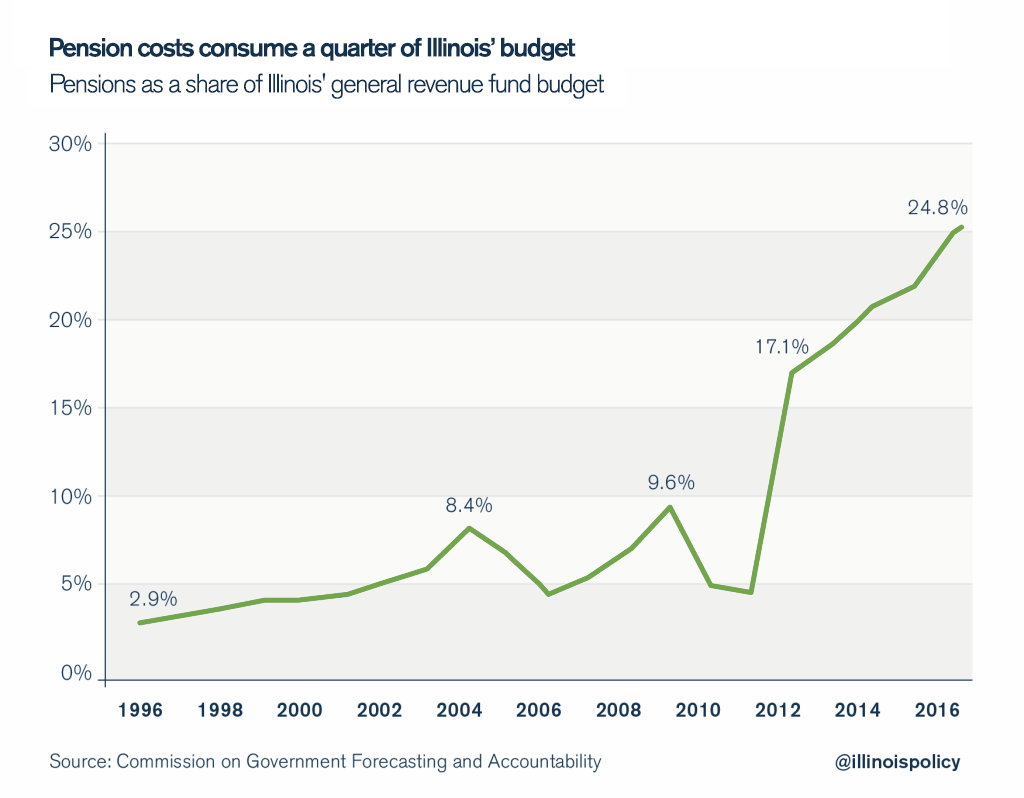

Social service providers, from those who help the developmentally disabled to those who treat drug addiction, are seeing their funding dry up as out-of-control pension costs swallow a quarter of the state budget.

Young teachers are being forced to pay into an insolvent state-run pension plan and given no other options to save for their retirements.

Because doctors know the state is a bad partner, many practices do not treat Medicaid patients, and Medicaid recipients still often rely on emergency rooms to access care despite the billions spent on Medicaid.

And for too long, Illinois’ college administrators have put themselves before students.

Tax hikes won’t solve any of those problems. In fact, they would only perpetuate these crises.

The Illinois Policy Institute’s 2018 Budget Solutions offers a plan that reverses the state’s failed course. The plan balances the state budget without tax hikes and implements many of the spending and economic reforms Illinoisans instinctively know are needed to create more jobs, generate higher pay, and provide a better living environment, but that are perpetually avoided by state politicians.

Without those reforms, Illinoisans will continue to protect themselves and their futures in the only way they can – by leaving.

Illinois experienced record out-migration in 2015, netting a loss of 105,000 residents. That’s the equivalent of losing almost the entire population of Springfield in just one year.1

And an October 2016 poll by the Paul Simon Public Policy Institute warns the exodus will only increase. Forty-seven percent of Illinoisans polled said they want to leave the state. Their number one reason? Taxes.2

Illinoisans can’t afford another tax hike. And Illinois can’t afford to further destroy its tax base.

Instead, politicians must enact the major spending reforms Illinois needs before they even utter the words “tax increase.” The good news is a full implementation of the Institute’s plan means there wouldn’t be a need for tax hikes.

The status quo is robbing Illinois of its future. Years of higher taxes, misplaced priorities and fake reforms have only served to drive people away.

Illinois has the people, the assets, the infrastructure and the location to once again be a beacon of prosperity in the Midwest.

The Illinois Policy Institute’s Budget Solutions 2018 sets Illinois back on that path.

Comprehensive property tax reform (state savings: $3.4 billion)

A three-step plan for comprehensive property tax reform

In Illinois, there is no tax that burdens residents more than property taxes. Illinoisans now pay the highest property taxes in the nation, and that burden is pushing many families out of their homes. Seniors can’t keep their homes in retirement, and middle-class families are being forced to find opportunities in nearby states.1

Yet high property taxes are only the symptom of larger problems: Illinois’ duplicative and overlapping local government units, costly local bureaucracies, state subsidies that prop up excessive spending by local governments, and state mandates such as prevailing wage requirements and collective bargaining rules, which drive up the cost of government operations.2

Thus, Illinoisans need comprehensive property tax reform that includes a property tax freeze, as well as reforms to shrink the number, size and cost of local governments and to eliminate the state mandates that increase costs for localities.

Only such comprehensive property tax reform will help avoid an income tax hike. Reforms outlined in the Illinois Policy Institute plan would save the state $3.4 billion, which would make up for almost half the state’s $7 billion deficit.

Illinois should undertake a three-part process to rein in property taxes and the cost drivers that keep them high:

Step No. 1: Freeze property taxes

Freezing local property taxes is the key to reducing government’s burden on Illinois residents.

Step No. 2: End the state subsidy shell games

Illinois’ tangled web of local government is funded not only by steep local property taxes, but also by state subsidies that funnel billions of dollars to local governments every year.

State officials like to dole out these subsidies because it grants them greater control over local governments. Local leaders like state subsidies because those funds allow them to spend money without having to bear the political cost of raising taxes locally. That means officials can funnel money where it’s most politically expedient without having to answer to local taxpayers. Ending state subsidies will save state taxpayers billions and force local officials to curb their excessive spending practices.

Step No. 3: Eliminate state mandates on local governments

Ending state subsidies and freezing property taxes will have an immediate impact on local communities’ budgets. To enable local governments to operate with reduced revenues, the state must reform many of the mandates – from prevailing wage requirements to collective bargaining rules – that drive up the cost of local government.

Step 1 of comprehensive property tax reform: Freeze property taxes

The problem: Property taxes fuel too many local governments

The high property taxes Illinoisans pay every year help fuel Illinois’ excessive number of local governments, expensive bureaucrats and school district administrations.

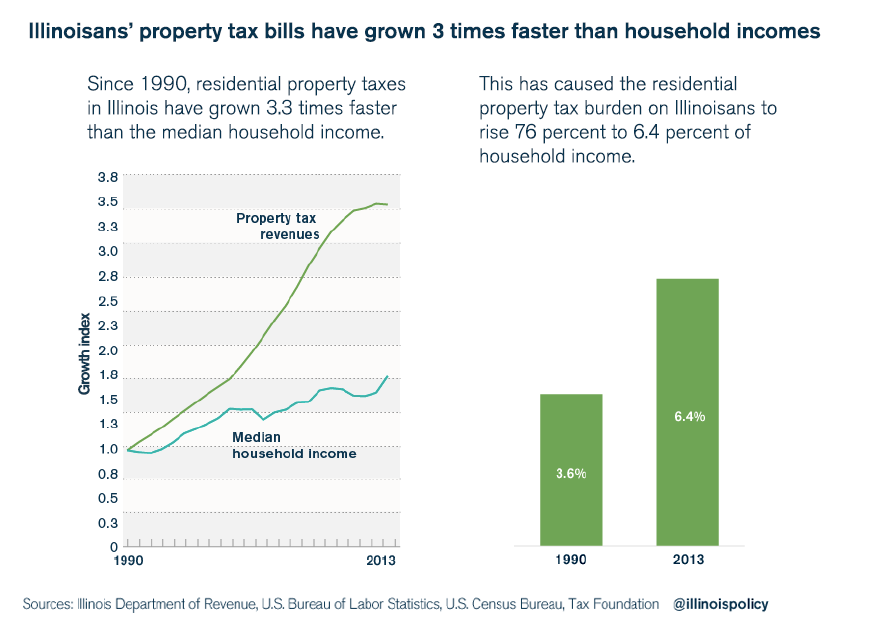

As local costs have grown, so have property taxes. Since 1990 alone, tax bills have grown three times faster than household incomes.3

As a result, property taxes are taking more money than ever out of residents’ wallets, consuming 6.4 percent of Illinoisans’ median household incomes in 2013. That’s nearly double the 3.6 percent property taxes consumed in 1990.

According to the nonpartisan Tax Foundation, Illinoisans pay the highest taxes in the nation when compared to the value of their homes. The average Illinoisan pays 2 percent of the value of his or her home in property taxes every year – double what homeowners in Missouri pay and 2.5 times what residents in Indiana and Kentucky pay.4

In some Illinois communities, residents pay 5 percent or more of the value of their homes in property taxes. For many, that’s more than they pay toward their mortgages each year. In those places – such as in Chicago’s Southland area – a homeowner will pay twice for his or her home over a 20-year period – once to purchase the home and a second time in the equivalent amount of property taxes.

The local government costs that property taxes fuel

Too many local governments

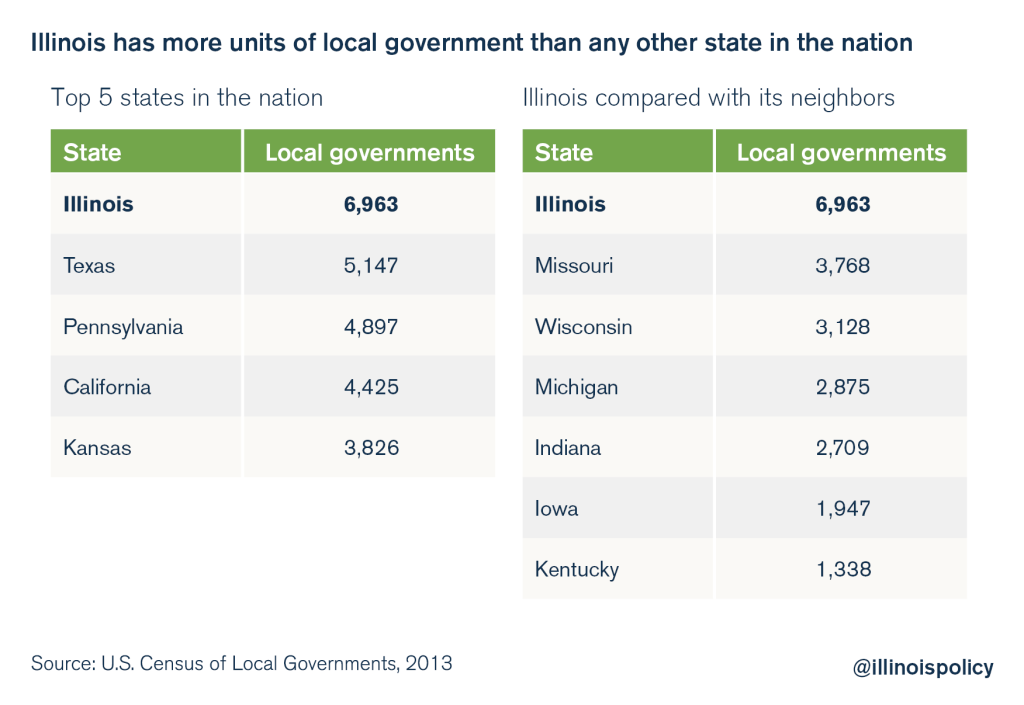

Illinoisans pay the highest property taxes in the U.S. to fund nearly 7,000 units of local government – the most in the nation and more than the local governments in Indiana, Kentucky and Iowa combined.5

Those taxes, and billions more in state subsidies to local governments, fuel wasteful spending, overly generous pension benefits and salaries for too many administrators, as well as unaffordable collective bargaining, prevailing wage and workers’ compensation costs of these thousands of local governments.

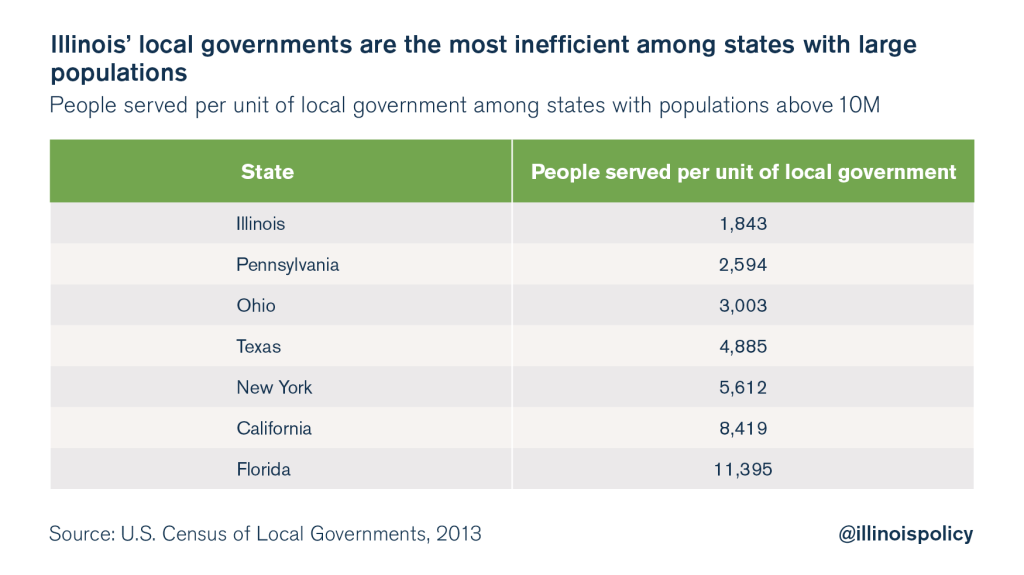

Those inefficiencies are revealed when the number of people Illinois local governments serve is compared with other large states. On a per capita basis, the average local government in Illinois serves just 1,800 people. 6

Local governments in other heavily populated states serve far more residents. For example, the average local government in California serves more than 8,000 people, or 4.5 times the number of people as Illinois, while Florida’s local governments serve on average nearly six times as many people as Illinois’ governments do.

Too many layers

Illinois’ record number of local governments is a problem due to the inefficiencies they create and the administrative costs they generate. In many communities, multiple government bureaucracies perform functions and deliver services that could be consolidated under a single entity.

Illinois has more layers of municipal government than any other state in the country. Over 60 percent of Illinoisans live under three layers of general-purpose local government (municipal, township and county governments). In 40 other states, residents only have to deal with, at most, two layers of municipal government.7

Illinois’ 1,431 townships are a particularly inefficient form of local government. They often provide services such as property assessment and road maintenance that county or city governments could easily perform.8

Beyond municipalities, Illinoisans pay property taxes for thousands of additional special districts such as schools, libraries, parks, forest preserves, fire protection, sanitation, transportation and even mosquito abatement districts. These special districts are often unnecessary or redundant, performing functions and providing services that could be consolidated or absorbed by other units of government.

Taken together, Illinois’ nearly 7,000 local governments form a vast, complicated web of taxing bodies. Many Illinoisans live under a dozen local governments or more, which makes it difficult for homeowners to hold those governments accountable for the disposition of the property taxes they collect, and the increases in the property taxes they impose.

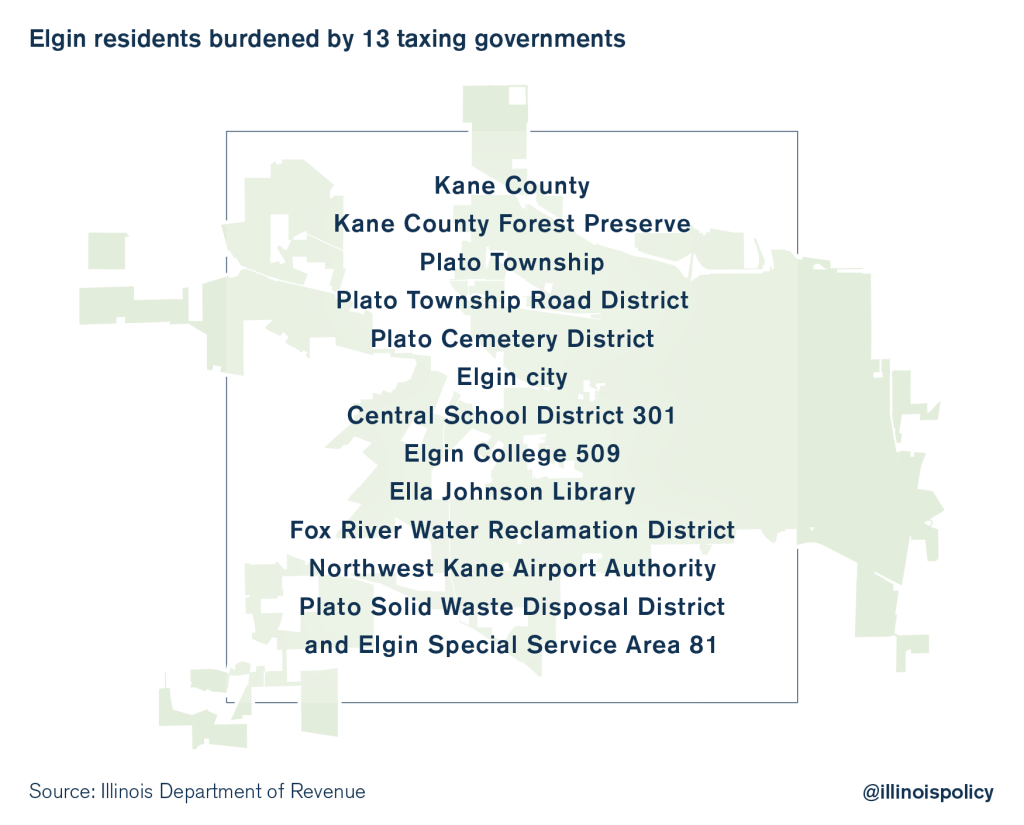

For example, some residents in Elgin live under a total of 13 taxing governments and their related pension funds, including: Kane County, Kane County Forest Preserve, Plato Township, Plato Township Road District, Plato Cemetery District, Elgin city, Central School District 301, Elgin College 509, Ella Johnson Library, Fox River Water Reclamation District, Northwest Kane Airport Authority, Plato Solid Waste Disposal District and Elgin Special Service Area 81.9

Too many expensive bureaucrats

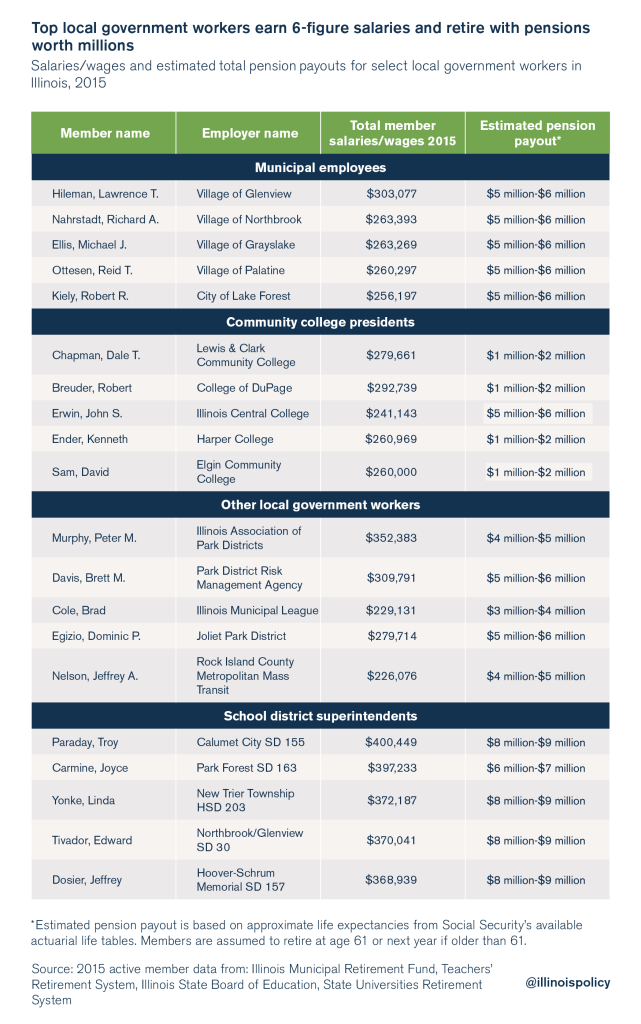

Having thousands of local governments means having to pay for the bureaucrats those governments employ. Many localities in Illinois provide high salaries and multimillion-dollar pensions to a significant number of administrators. In most cases, the half-dozen or more local governments in a community will employ a set of administrators – e.g., office managers, human resource directors, computer technicians, etc. – that could each be merged if those local governments consolidated.

Top local administrators are particularly costly. Such government employees often receive six-figure salaries and millions of dollars in pension benefits over the course of their retirements. For example, Troy Paraday, the superintendent of Calumet City School District 155, earns approximately $400,000 a year and will receive almost $9 million in pension benefits over the course of his retirement.10

Another administrator, Dale Chapman – the head of Lewis and Clark Community College – makes almost $280,000 in base pay even as Illinois colleges and universities continue to hike tuition rates for students. (Chapman earned nearly $540,000 in total compensation in 2014 when bonuses and other compensation are included.)11

And Peter Murphy, who runs the Illinois Association of Park Districts, earns $350,000 in wages and can expect more than $4 million in pension benefits over his retirement.12

Too many school district administrations

Some of the most inefficient and overlapping bureaucracies can be found among Illinois’ 859 school districts, the fifth-most in the nation.13

Nearly 25 percent of Illinois school districts serve just one school, and over one-third of all school districts have fewer than 600 students. An additional layer of district administrators on top of school administrators in these small districts is wasteful and unnecessary.14

The number of school district administrators in Illinois has grown far faster than the number of students and parents they are employed to serve. Between 1992 and 2009, the number of district administrators grew by 36 percent in Illinois, 2.5 times as fast as the 14 percent growth in students. If the number of administrators had simply grown at the same rate as the state’s student populations, Illinois would have nearly 19,000 fewer administrators and would be spending $750 million less in compensation costs annually.15 In all, there are over 9,000 school administrators – from principals to superintendents – who make six-figure salaries and who will each receive $3 million or more in pension benefits over the course of retirement.16

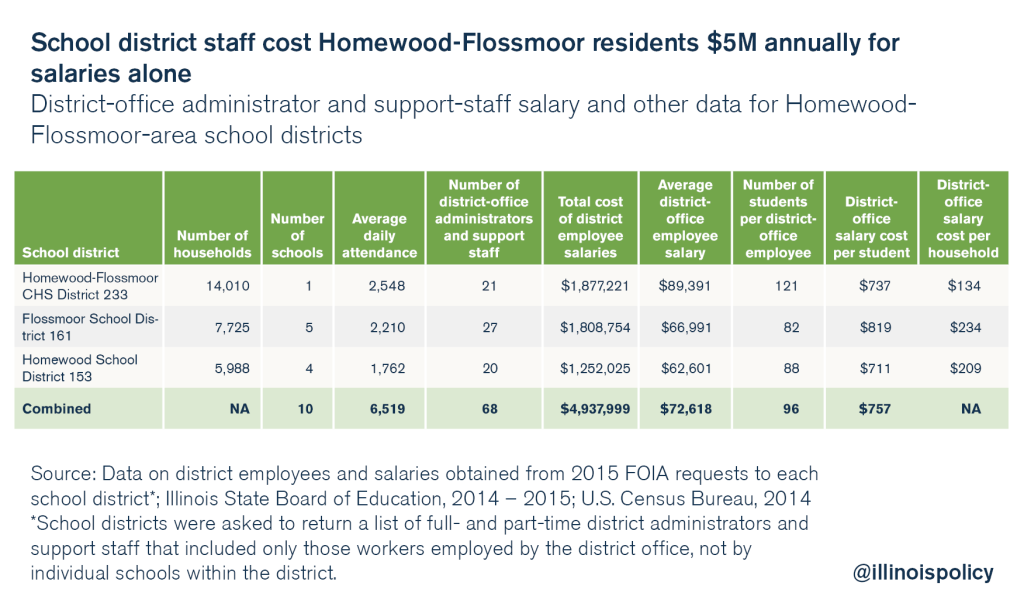

The cost of local bureaucracies is especially stark in some of the state’s property-poor areas – where property values are relatively low. For example, in the Homewood-Flossmoor area just south of Chicago, residents face declining home values, homes “under water” with respect to their mortgages, foreclosures and effective property tax rates of nearly 5 percent.17

A large portion of Homewood-Flossmoor residents’ property taxes is dedicated to the area’s three school districts – a high school and two nearly coterminous elementary districts. Those districts could be consolidated into one unit district to save on administrative costs.

Until that happens, the residents of Homewood-Flossmoor will continue to pay for three school districts, including a total of 68 district-office employees who collectively cost residents $5 million a year for salaries alone.18

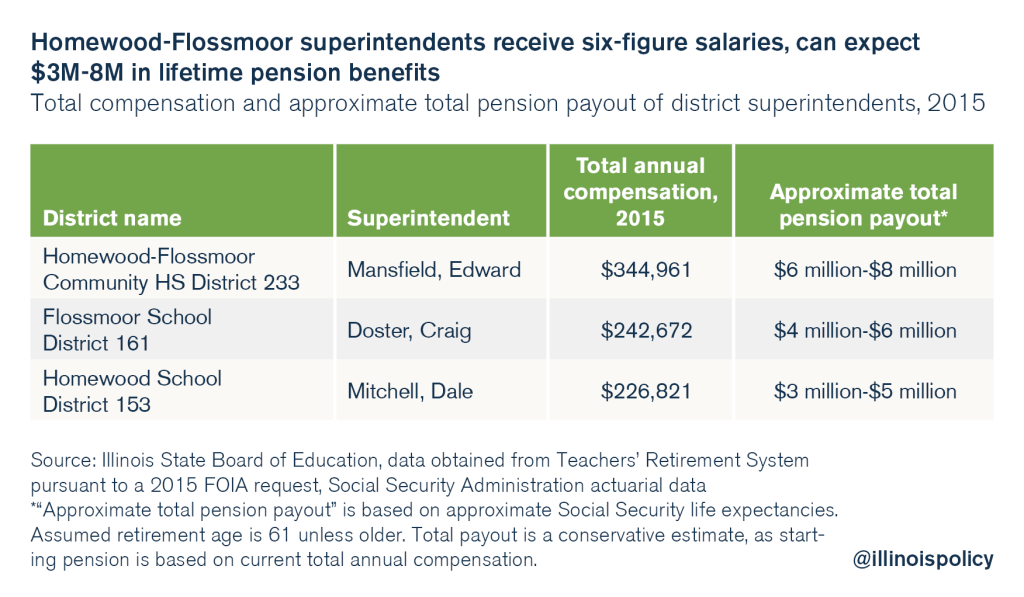

That includes the cost of three separate superintendents who each receive compensation of over $225,000 a year and can expect to receive anywhere from $3 million-$8 million in pension benefits over the course of their retirements.19

Consolidation of small districts (not of schools themselves) and of districts coterminous with each other could save taxpayers hundreds of millions a year in administrative costs, and billions more in pension costs. Yet Illinoisans across the state continue to pay property taxes to fund district bureaucrats’ generous salaries, benefits and pensions.

In sum, the nation’s highest property taxes fund the nation’s highest number of local governments and their costly bureaucracies.

The solution: Freeze and cap property taxes

Meaningful and lasting tax relief will only come through reforms that reduce the number of Illinois’ nearly 7,000 units of local government, reform government worker salaries and benefits, and lower the costs of local government operations through changes in workers’ compensation, unfunded mandates, collective bargaining and prevailing wages.

In the meantime, however, lawmakers can freeze local government tax levies on property (i.e., the total amount of property tax revenues a local government collects annually).

1. Freeze property taxes

The Institute’s tax plan freezes the property tax levy of every local government in Illinois for five years (including home rule and non-home rule local governments). Absent the passage of a local referendum to raise property taxes or the construction of new property, the amount each local government collects in property taxes would be frozen at its current amount.

That means the $28 million in property taxes the city of Springfield currently collects on properties, for example, will stay at $28 million for the next five years. And the $1.3 million in property taxes the Oak Forest Park District collects on current properties today will stay at $1.3 million for the next five years.20

The freeze will help Illinoisans’ incomes catch up with their tax bills and allow more homeowners to stay in their homes.

2. Cap the growth in property taxes at Illinoisans’ ability to pay

Under current law, growth in property taxes is tied to inflation for a vast majority of local governments in Illinois. Those governments are subject to the Property Tax Extension Limitation Law, or PTELL, which limits the annual growth of governments’ property tax levies (i.e., the total amount of property tax revenues a local government demands annually) to 5 percent or the rate of inflation, whichever is less.21

Even with those limits on local government revenue growth, Illinois’ existing property tax cap laws haven’t reduced the tax burden on individual taxpayers. Homeowners across Illinois have seen their property tax bills grow far faster than their incomes.

Illinoisans’ future tax bills shouldn’t grow automatically based on inflation. Instead, any growth in future tax bills should be based on Illinoisans’ ability to pay.

After the plan’s initial five-year tax bill freeze, the annual growth in local government levies will be based on the annual growth in Illinois’ statewide median household income – with a maximum annual growth of 2 percent and a minimum of zero.22

More closely connecting governments’ property tax growth to homeowners’ ability to pay will mean Illinoisans can better manage their tax bills from year to year.

3. Allow tax increases only through referendum

Freezing property taxes will tempt local officials to raise other local taxes and fees instead of enacting reforms.

To further protect taxpayers and encourage real reforms, any local governments’ attempts to raise additional revenue through any form of tax or fee should be subject to voter approval.

Under the Institute’s plan, any local government that seeks additional revenues must submit its request to taxpayers through a special referendum. To pass, two-thirds of the voters must approve the referendum.

Step 2 of comprehensive property tax reform: End the state subsidy shell games

The problem: State subsidies fuel local excesses

Illinoisans pay the nation’s highest property taxes to support one of the most expensive webs of local government bureaucracies in the country.

But even those taxes aren’t enough to fully fund Illinois’ many local bureaucracies. Billions more in state taxpayer dollars – over and above the $27 billion in property taxes local taxpayers already pay – are funneled to local governments in the form of state subsidies.23

From state income tax subsidies to the payment of local pension costs, state funding helps prop up perks and expenses that would otherwise be unaffordable for local governments.

State officials like to dole out these subsidies because that grants them greater control over local governments. Local leaders like the subsidies because the funds allow them to spend money without having to bear the political cost of raising taxes locally. That means officials can funnel money where it’s most politically expedient without having to answer to local taxpayers.

The state subsidies that fuel these costs include:

- $1.3 billion of state income tax collections paid out to cities and counties not based on need, but on their share of state population, and hundreds of millions more in other state subsidies.24

- $970 million to cover the yearly pension costs of teachers (another $450 million in state subsidies also goes to community colleges and universities to cover the yearly pension costs of their employees).25

- $250 million in subsidies to school districts to circumvent local property tax caps.26

That’s why the local bureaucratic tangle burdening taxpayers across the state will only end when its funding sources – property taxes and state subsidies – are reformed.

The local excesses state subsidies fuel

The state subsidies provided to local governments fuel excess spending on everything from workers’ compensation to prevailing wages.

Local officials are able to spend recklessly because they know state subsidies will prop up their bad habits. The following are just a few examples of excessive local government benefits and expenses.

Excessive benefits: From pension spiking to sick leave accumulation

Local governments use state dollars to provide overgenerous salaries and benefits to avoid conflict with their local government-worker unions – all without having to answer to local taxpayers for the resulting additional costs.

All local governments in Illinois are stuck with a wide variety of employee compensation costs, but Illinois’ 859 school districts illustrate particularly well how state subsidies increase employee compensation.

School districts consume nearly two-thirds of property tax revenues and more than half of the subsidies provided to local governments in Illinois, so the agreements districts reach on employee compensation and benefits have a massive effect on Illinoisans’ tax bills.27

A prime example of how state subsidies affect compensation can be found in the impact of the state paying the cost of teachers’ pensions.

Currently, the state – and therefore taxpayers across Illinois – pays the employer contribution of teachers’ pensions on behalf of school districts outside of Chicago. In doing so, the state is essentially paying for districts’ spending decisions on salaries and pension-boosting perks over which it has no control.

Because they don’t bear the cost of pensions, school districts have an incentive to offer pension-boosting benefits to teachers and other district workers, which increases pension costs for all taxpayers in the long run.

Pension spiking

The state’s subsidies of teacher pension costs allow districts to practice pension spiking – end-of-career salary hikes designed to boost future pensions – which increase compensation costs for both state and local taxpayers.

Pension spiking by districts continues despite a 2005 law that requires local districts (taxpayers) to reimburse the state for the pension costs of spikes greater than 6 percent a year. Those 6-percent-plus salary increases cost local taxpayers more than $38 million over the past decade in payments to the Teachers’ Retirement System alone.28

However, the four-year, 6 percent increases school districts automatically give teachers when they commit to retiring are primarily driving the spiking costs. That policy, which boosts a teacher’s salary by almost 25 percent, means a career worker with an average salary of $73,000 will earn approximately $250,000 more during the course of her retirement when compared with 2 percent annual raises.29

Sick leave

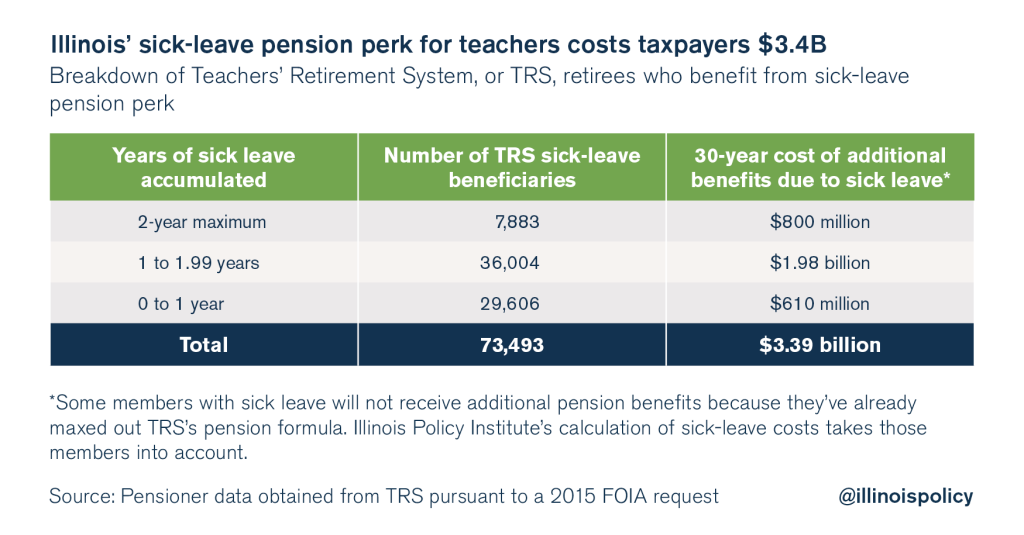

Another benefit local school districts grant is the ability of teachers to use unused sick days to boost their pensions. Illinois teachers can accumulate and apply up to two years of unpaid sick leave to their years of service credit, which in turn boosts their starting pension benefit.30

As of 2015, over 73,000 retired teachers in Illinois had unpaid sick leave applied to their pension benefits.31

Two years of additional service credit can significantly boost a teacher’s total pension benefit. A career teacher who has accumulated two full years of sick leave will on average receive more than $165,000 in additional pension benefits over the course of her retirement.

In total, the unpaid sick leave perk costs Illinoisans approximately $100 million a year in additional pension costs – which will amount to nearly $3.4 billion over the next three decades.

Pension pickups

State subsidies to school districts also encourage the practice of teacher pension pickups.

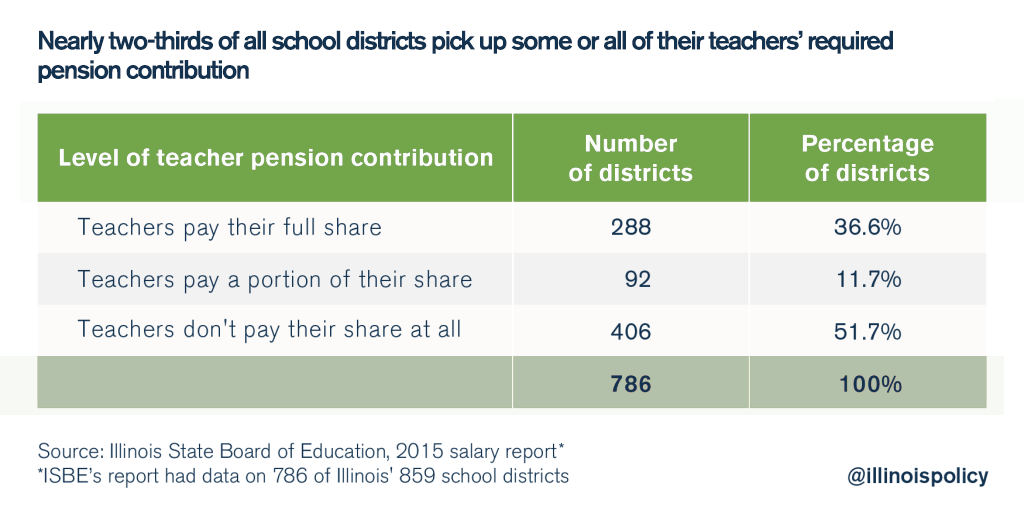

Teachers are obligated by law to pay 9.4 percent of their salary into the state retirement system. But over the last few decades, school districts began paying, as a benefit, the teacher’s required contribution. This practice is called a “pickup.”

Today, nearly two-thirds of all school districts pick up some or all of their teachers’ required pension contribution. In total, teacher pension pickups cost local taxpayers approximately $380 million annually.32

Salaries

The billions of dollars the state of Illinois provides to school districts every year also allows school districts to use outdated pay schemes that cost local taxpayers hundreds of millions of dollars annually in unnecessary compensation.33

A vast majority of teacher pay isn’t based on merit in Illinois. Instead, it’s based on collectively bargained steps and lanes, a convoluted system that pays all teachers with the same years of work (steps) and education level (lanes) the same salaries, regardless of individual teachers’ skills, effectiveness or achieved outcomes for students.

Numerous studies have demonstrated that boosting teacher pay based on a teacher’s education is inefficient and does nothing to enhance student achievement.34 Yet school districts across Illinois spend more than $900 million a year giving raises to teachers who earn their master’s degrees.35

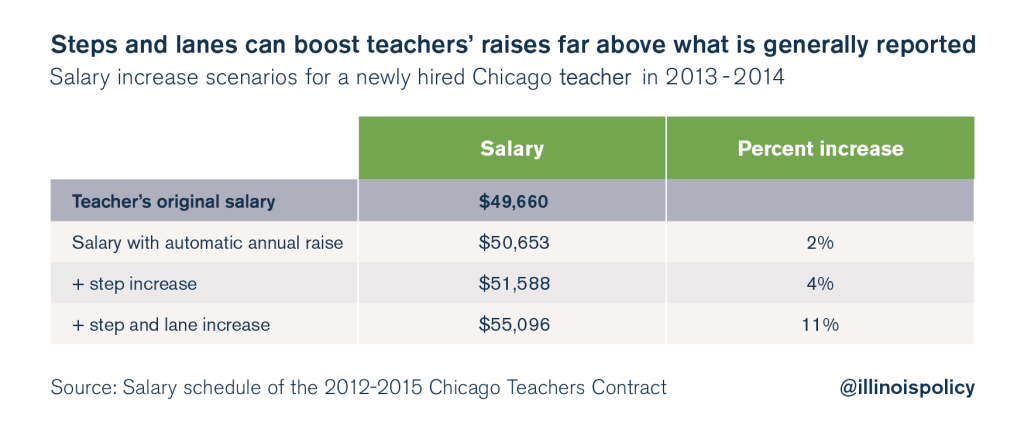

The steps and lanes system can also deceive local taxpayers into thinking their teachers are getting smaller raises than they actually are. Typically, teachers unions and the media report automatic “across the board” annual raises (usually ranging from 2-3 percent) only when a new teachers contract is agreed upon. However, the salary increases individual teachers receive annually are generally much higher than that due to steps and lanes.

For example, a newly hired Chicago Public Schools, or CPS, teacher with a bachelor’s degree in 2013 received an annual salary of $49,660 under the rules of the CPS salary schedule.36

In 2014, that teacher received a 2 percent automatic annual raise – the raise unions and the media generally referred to. However, the teacher’s total raise was higher than that due to the nature of steps and lanes. By working an extra year, the teacher moved up a “step” and received a total raise of 4 percent – double what was generally reported.

And if the teacher earned a master’s degree in 2013, she would also be entitled to move up a “lane” in 2014 as well. In total, she would receive a raise of 11 percent, five times greater than the raise generally reported.

Without billions in state aid and the state’s pickup of downstate teacher pension costs, providing such benefits to teachers, from sick leave to step and lane salary increases, would not be affordable for most school districts.

The nation’s 7th-highest workers’ compensation costs

The state’s billions in subsidies also fuel additional spending by local governments. Without the billions in extra dollars the state provides to them, local governments could not afford – and therefore would not undertake – the projects that result in these additional expenses.

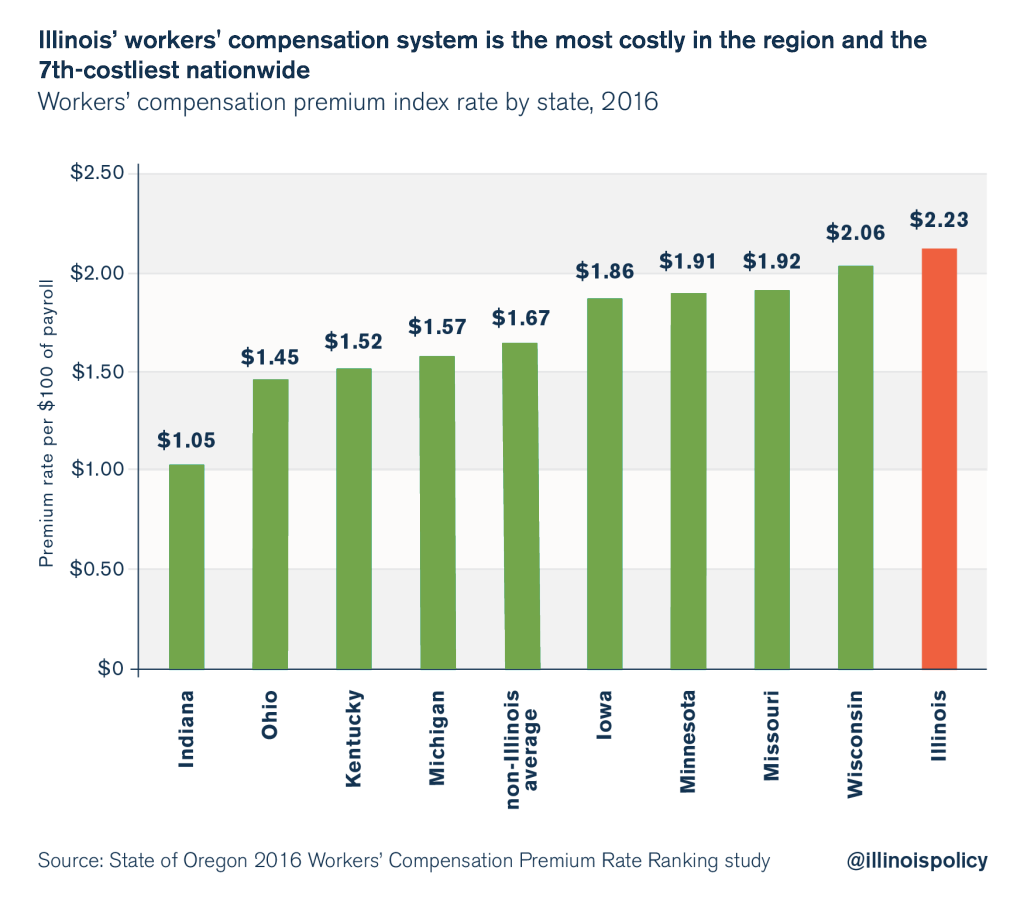

Illinois’ compensation system for workers injured on the job is the most costly in the region and the seventh-costliest nationwide, according to a 2016 biennial study by the state of Oregon.37

The same heavy costs imposed on private sector employers are also imposed on taxpayers who cover the workers’ compensation costs for local government payrolls, and Illinois’ expensive workers’ compensation system adds billions to the labor costs for public construction projects.

Illinois employers – including local governments – often pay as much as three times more in workers’ compensation costs than comparable businesses in Indiana.38 The city of Chicago, for example, spends over $100 million a year on workers’ compensation expenses.39 The city of Waukegan spends at least $3 million annually.40

In total, Illinois’ municipal and county governments – and therefore local taxpayers – pay $270 million a year for workers’ compensation costs. School districts and other local governments cost local taxpayers an estimated $500 million in workers’ compensation expenses annually.41

Six-figure prevailing wage costs

A combination of state-imposed prevailing wage rules and state subsidies also drive local governments’ spending higher, especially on local construction and maintenance projects.

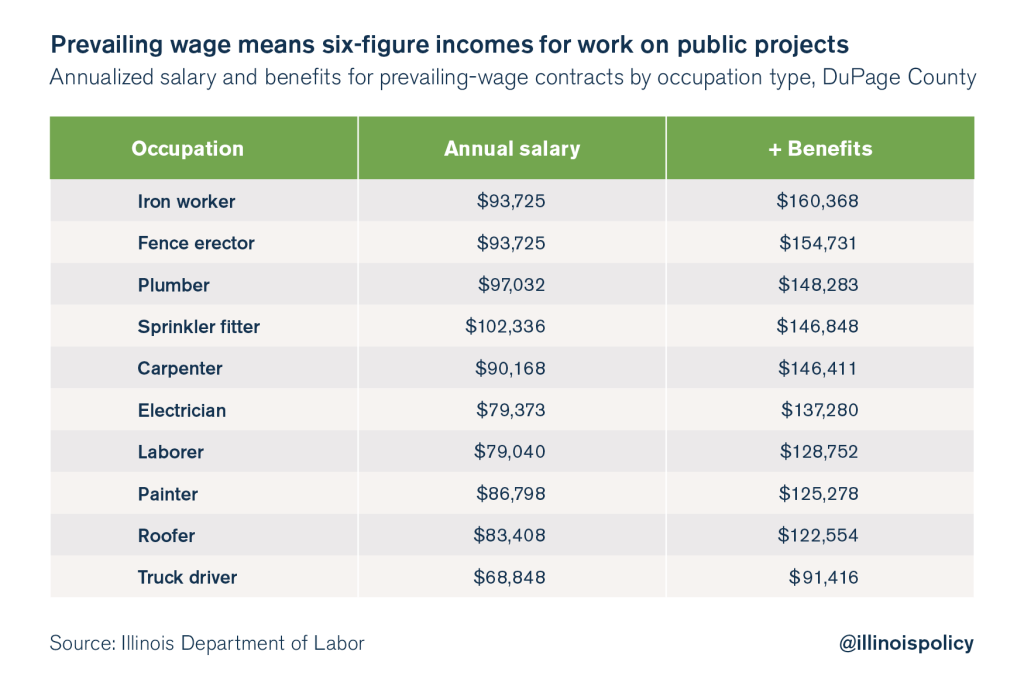

Prevailing wages are hourly minimum wages placed on government contracts for public work. This means if the government funds any part of a project like repairing roads or fixing water pipes, contractors are required to pay the (most often union-level) wages the Illinois Department of Labor sets.42

Under current law, counties have the power to research their own prevailing wage and reconcile it with the (often higher) Department of Labor’s determined wage, but most don’t. Most local governments would rather pay the higher prevailing wages (often with state-provided subsidies) than spend time and resources on determining their own prevailing wage.

This ends up hitting many local governments with millions of dollars in additional costs annually.43

High prevailing wages and additional benefits often result in six-figure compensation packages for laborers who work on public projects in counties across Illinois. For example, the average compensation package for workers who receive prevailing wages in Cook and Sangamon counties is over $110,000.44

Private-sector taxpayers in those counties earn far less – the median earnings for workers are $34,990 in Cook County and $34,521 in Sangamon County.45

And prevailing-wage workers in DuPage County on average receive even higher compensation when their benefits are included. For example, a fence erector working for the county can expect to receive over $150,000 in annual compensation.

The above are only a few examples of the cost of prevailing wages. Many other counties pay excessive prevailing wages they could not afford without the millions they receive in subsidies from the state.

The solution: Stop state subsidies that fuel local excesses

Too many state subsidies provide local politicians with the luxury to fund unnecessary local perks and pay for avoidable expenses without having to raise the taxes to pay for them. That means officials can funnel money where it’s most politically expedient without having to answer to local taxpayers.

Those resulting higher expenses that burden state and local taxpayers will only end when state subsidies are eliminated and local officials are forced to reform how their governments operate.

Eliminate funds like the Local Government Distributive Fund (State savings: $1.75 billion)

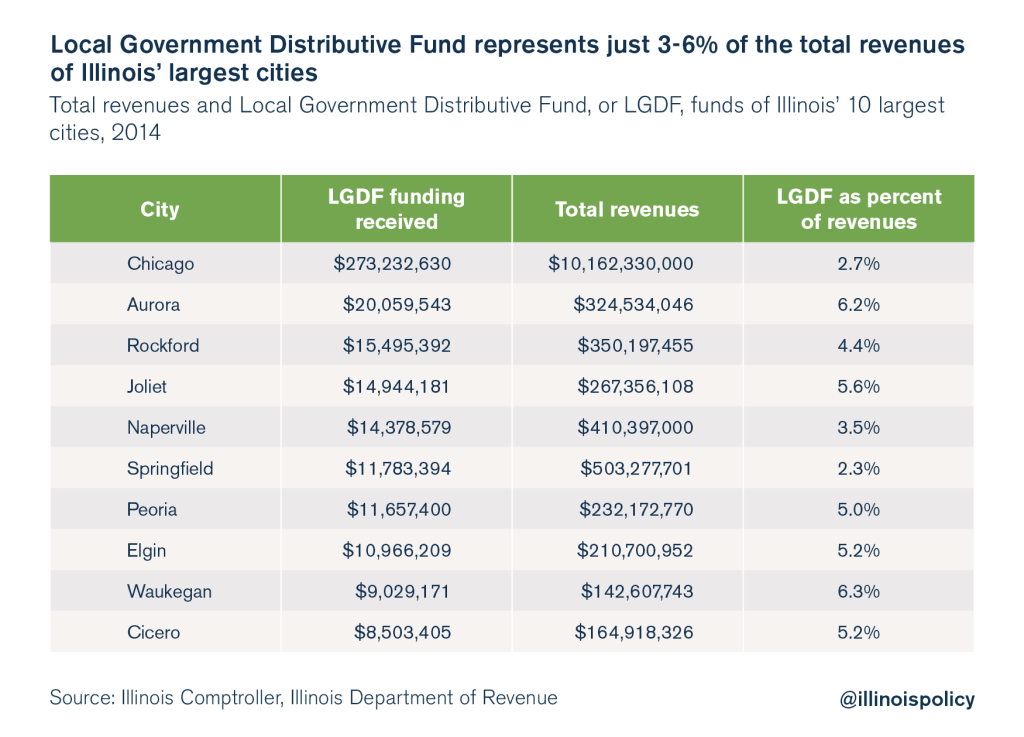

One of the state’s subsidies to local governments is the $1.3 billion Local Government Distributive Fund, or LGDF. The LGDF distributes a portion of state-collected income taxes to local governments each year, not based on need or any particular purpose, but simply on each government’s share of statewide population.

The LGDF typically provides cities and counties with 3 to 6 percent of their total revenues.46

Local officials will claim LGDF funds local services and keeps local taxes low. But the facts – the nation’s highest property taxes and the billions spent on perks and duplicative bureaucracies – show the opposite.

The state should end the state-local funding shell game that occurs through the LGDF. All LGDF distributions to counties and municipalities with populations above 5,000 should be ended.47

In addition, the Downstate Transit Fund, which uses state-collected sales taxes to support public transportation in rural areas, and all other state subsidies should be eliminated as well.

Taxpayers deserve to stop paying for the excessive local perks and expenses that the LGDF and other funds help pay for.

Stop subsidizing local pensions (State savings, higher education: $450 million, K-12: $970 million)

Currently, the state pays the employer contribution of teachers’ and university and college workers’ pensions on behalf of school districts outside of Chicago and universities. In doing so, the state is essentially paying for spending decisions on salaries and pension-boosting perks over which it has no control.48

School districts and state universities should be held accountable and responsible for the total cost of compensation for their employees.

The responsibility for paying the employer’s pension contribution for teachers and university employees should be shifted back where it belongs – to local school districts and universities.

Shifting the cost of pensions will save the state $1.5 billion in annual pension (normal) costs.49 While the state will continue to pay off the teachers’ and state universities’ billions in unfunded pension debt, local school districts and universities would pay for the annual pension costs – the pension benefits their workers accrue for working one additional year – moving forward.

The shift will encourage greater fiscal responsibility at the district and university levels. School districts and universities will moderate their employees’ salary and benefits when they have to bear the resulting pension costs.

Eliminate special carve-outs for select school districts (State savings: $250 million)

Every year, hundreds of millions in state education funds are carved out for a few school districts whose revenues are affected by local property tax caps and special economic zones.

The money those select few districts receive – with the majority going to CPS and Cook County districts – is nothing more than multimillion-dollar subsidies to relatively property-wealthy districts. These subsidies, resulting from the PTELL and Tax Increment Financing, or TIF, districts, defeat the whole purpose of the state providing needs-based education funds to districts across the state.50

The state cannot afford to give away subsidies to a select few districts when massive budget deficits and pension payments are cutting into funding for classrooms. Illinois lawmakers must eliminate the PTELL adjustment and TIF subsidy to end school districts’ ability to circumvent property tax caps.

Step 3 of comprehensive property tax reform: Eliminate state mandates on local governments

Enacting a property tax freeze and ending the state subsidy shell games are essential steps of comprehensive property tax reform in Illinois.

But those reforms alone won’t be enough to fix the state. Local officials must have greater control over their own budgets so they can lower significant cost drivers and reform how local government is delivered.

Unfortunately, the deck has always been stacked against local officials who wish to enact reforms. Many of the laws Springfield lawmakers impose – from collective bargaining rules to prevailing wage requirements and other unfunded mandates – control local governments’ budgets.

That has to change if Illinois is to fix the financial problems afflicting local government. In exchange for freezing local governments’ property taxes and eliminating state subsidies, the state should enact the following comprehensive reforms:

Collective bargaining reform (Local savings: $1 billion-$2 billion)

The collective bargaining rules the state imposes on local governments have a drastic effect on government spending for employee compensation. In 2014 alone, collective bargaining rules inflated state and local government spending by $4 billion to $9 billion.51

The problem is the rules of collective bargaining are state-imposed, offering no flexibility to Illinois’ local governments, which are all different sizes, serve different populations, and are operating in different economic climates.

The state’s one-size-fits-all rules should not hamstring local governments. Instead, individual local governments should have the right to reform their collective bargaining processes to match their unique economic and budgetary situations.

The state must pass collective bargaining reform that empowers local communities to negotiate more affordable contracts. Removing some of the more stringent rules of the collective bargaining process, such as strike protection and forced arbitration, but still requiring compulsory bargaining, would save local governments $1 billion to $2 billion dollars annually.

Prevailing wage reform (Local savings: $280 million)

Illinois’ Prevailing Wage Act mandates high wages for construction workers on capital projects that receive public funding. This results in needlessly higher construction costs for local governments as those wages stifle competition and discourage contractors from competitively bidding on projects.52

And as with collective bargaining rules, current prevailing wage laws offer little flexibility for local governments. Wages, determined by the Illinois Department of Labor, are set countywide and are usually based on union workers’ compensation. Under current law, counties have the power to research their own prevailing wage and reconcile it with the (often higher) Department of Labor’s determined wage, but most don’t. The difficulty and inconvenience of determining their own prevailing wage causes most counties to simply agree to the often higher prevailing wages the state determines.

As a result, local governments that exist in the same county but have vastly different economic and budgetary situations are forced to pay the same amount for construction work.

The state should pass prevailing wage reform that allows local governments to determine their own adequate rates of compensation for construction and other contract work. Such reforms could save local governments $280 million annually.

Reform unfunded state mandates (Local savings: $200 million)

Besides the more prominent mandates imposed on local governments – collective bargaining, pension rules, prevailing wage requirements – hundreds of other rules exist that impose significant financial burdens on the local governments that are subject to them.

The state’s Local Government Consolidation and Unfunded Mandates Task Force recently reported that there are over 250 unfunded state mandates on the books today, with an average of eight new unfunded mandates added per year.53

State mandates often force local governments to provide services or fulfill reporting requirements many localities feel are unnecessary and sometimes even counterproductive. They restrict local governments’ ability to adjust to changing budgetary realities.

And, as with prevailing wage and collective bargaining requirements, one-size-fits-all state mandates deny vastly different local governments the flexibility they need to manage their budgets.

For example, school districts across Illinois are burdened with a physical education mandate. The state requires all students to take a physical education class instead of additional math, reading or other academic class. Just by allowing K-12 students to opt out of gym class if they play a sport or partake in some other organized physical activity outside of school could collectively save districts hundreds of thousands of dollars every year.54

Reforming the hundreds of unfunded mandates the state imposes on local governments will allow local governments to structure themselves in a way that best meets the needs of their budgets, taxpayers and public employees.

Illinois school districts alone would save $200 million annually if the state’s unfunded mandates were reformed.55

Workers’ compensation reform (Local savings: $200 million)

Illinois’ workers’ compensation system is the most costly in the region and the seventh-costliest nationwide. Illinois employers – including local governments – often pay as much as three times more in workers’ compensation costs than comparable businesses in Indiana. In total, Illinois’ local governments pay at least $700 million a year in workers’ compensation costs.56

Illinois lawmakers could help reduce costs for local governments by passing a reform law that adopts the federal definition of catastrophic injuries for the Public Safety Employee Benefits Act and eliminates the effective bump in take-home pay given to some injured government workers under the Public Employee Disability Act.57

In addition, state lawmakers should make several changes to the state’s Workers’ Compensation Act, including putting Illinois’ wage-replacement rates in line with those in surrounding states, eliminating the increase in take-home pay for some injured workers, tying medical reimbursement rates to Medicare or group health rates and eliminating the financial incentives for doctors to overprescribe opioids and other dangerous drugs.

Depending on the changes implemented, workers’ compensation reform could provide Illinois local governments with savings of $200 million per year in payroll costs alone.

Local government consolidation

Illinois’ 7,000 units of local government – the most in the nation – are extremely expensive for taxpayers due to the inefficiencies they create and the administrative costs they generate. In many communities, multiple government bureaucracies perform functions and deliver services that could be consolidated under a single entity.

Unfortunately, Illinois’ law makes it difficult to successfully pursue consolidation efforts. In many cases, it’s more difficult to consolidate local governments than it is to amend the Illinois Constitution.58

The state should simplify the process to consolidate or eliminate local governments so it is no harder than the process to amend the Illinois Constitution via referendum.

Consolidating local governments will save Illinoisans millions of dollars annually. Recent consolidation efforts in DuPage County will save taxpayers there almost $150 million due to new shared services and employee compensation reforms.59

Consolidating school districts comes with unique challenges – it is the one type of local government residents are generally unwilling to change. Serious consolidation of the state’s 859 school districts will only happen when the state partners with local districts to provide a cooperative solution.

To that end, the Illinois General Assembly should authorize the creation of an official District Consolidation Commission, which would function in a manner similar to the federal government’s Defense Base Closure and Realignment Commission. The commission’s consolidation recommendations would be approved by an up or down vote in the General Assembly, meaning no amendments would be permitted.60

By cutting the state’s school districts in half, local taxpayers could experience operating savings of nearly $130 million to $170 million annually and could conservatively save the state $3 billion to $4 billion in pension costs over the next 30 years.

End pension pickups (Local savings: $375 million)

In Illinois, most public school teachers don’t pay their required 9.4 percent employee contributions toward their pensions. Instead, many school districts pick up, as a benefit, some or all of the teachers’ required payments.

Today, nearly two-thirds of all school districts pick up some or all of each teacher’s required contribution.61

This means local taxpayers are not only footing the bill for the massive shortfall in the teachers’ pension plan, but also for the individual employee contributions each teacher is supposed to make.

Illinois lawmakers should outlaw the practice of pension pickups. Teachers should pay their share of the costs associated with their own retirement benefits. That’s a simple standard across most industries, public and private. Outlawing teacher pension “pickups” would save Illinois school districts about $375 million annually.

Municipal bankruptcy

Due to the state’s numerous mandates, local governments in Illinois often don’t have the power to make the necessary major reforms to keep costs under control. Yet, even in the most extreme cases of fiscal instability, bankruptcy is not an option.62

This leaves officials with fewer options as they balance their budgets and often leaves taxpayers stuck paying higher taxes and fees.

This is especially true for local governments struggling with pension debt. Local governments have their hands tied when it comes to pension reform. The Illinois state legislature sets municipal pension laws – retirement ages, cost-of-living adjustments and benefit formulas – with no regard to whether local budgets or taxpayers can afford them.

That means local governments can’t reform the largest cost driver in their budgets. And when pensions push local budgets to the brink of collapse, local officials aren’t able to file for bankruptcy to help reorganize debts and relieve stress on both taxpayers and budgets.

Local governments should have more control over how they operate. Illinois state lawmakers should pass a law to allow Illinois municipalities the option to file for bankruptcy under Chapter 9 of the U.S. Bankruptcy Code as an option of last resort.

End Illinois’ pension crisis through self-managed plans (state savings: $1.65 billion)

The problem: Illinois’ pension system fails both state workers and taxpayers

Illinois’ pension math simply doesn’t work.

It doesn’t work for pensioners, who are worried about their collapsing retirement security. It doesn’t work for younger government workers, who are forced to pay into a pension system that may never pay them benefits. It doesn’t work for taxpayers, who pay more and more each year toward increasingly insolvent pension funds. And it doesn’t work for Illinois’ most vulnerable, who have seen vital services cut to make room for growing pension costs.

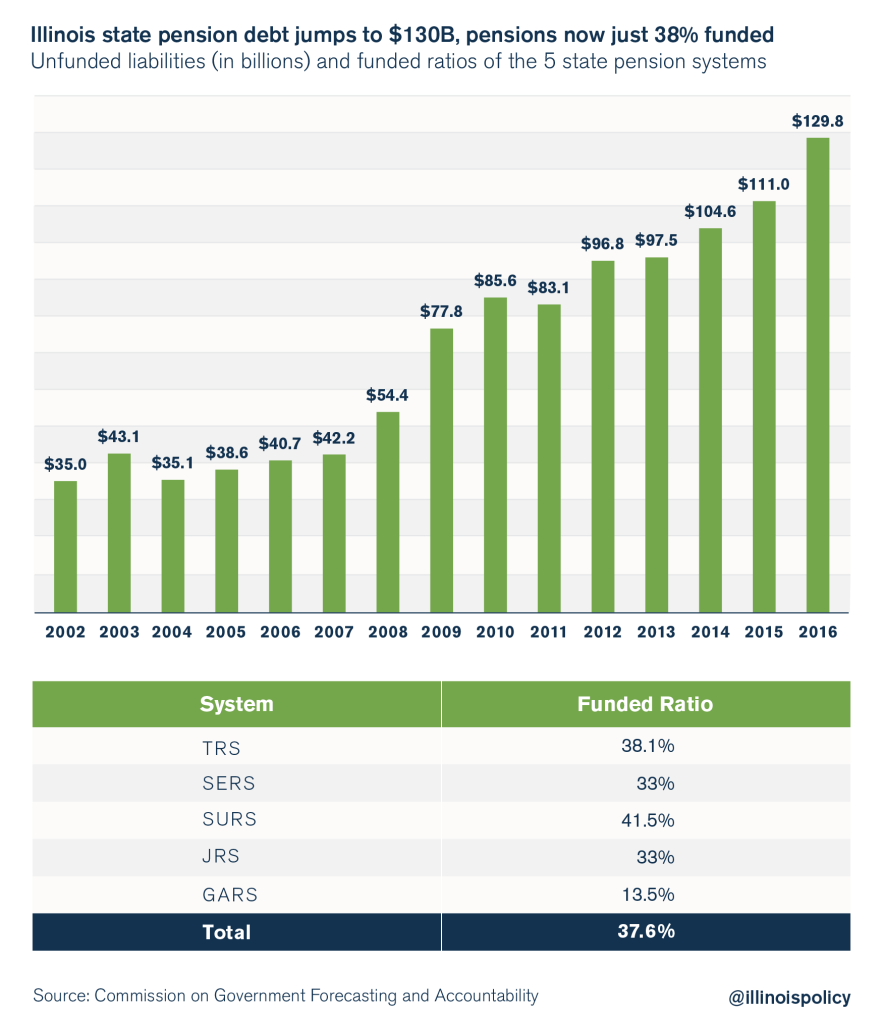

This crisis is the result of skyrocketing benefits, not underfunding. For thirty years, Illinois politicians changed rules and gave away perks that supercharged promised pension benefits. Today, pension benefits are too unrealistic for state workers to count on and too rich for taxpayers to pay for.

Benefits have grown so much that politicians dramatically reduced them in 2010. New workers are now stuck in a substandard, unfair Tier 2 system and are forced to subsidize the benefits of older workers.1

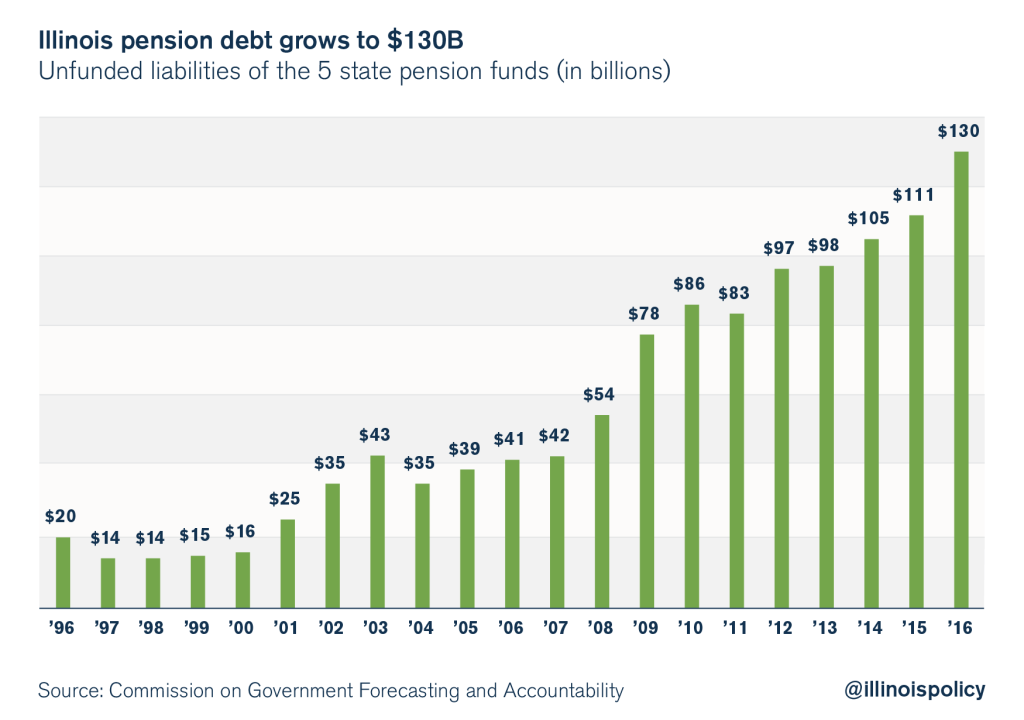

In fiscal year 2017, taxpayers will pay nearly $8 billion for pension contributions alone. In fiscal year 2018, that payment is projected to be nearly $9 billion. These payments do nothing to stem the growing tide of Illinois’ $130 billion in pension debt, which comes out to $27,000 per household.2

It’s no wonder many retirees fear they might lose their pensions. The funds have only 38 cents on hand today for every dollar needed to pay out future benefits – a level that would put private pensions in bankruptcy many times over.

Younger workers have even more cause for worry – they may never see a pension. The situation is even worse for those in stuck in Tier 2, the substandard tier of pensions created in 2010. Not only may they never see a pension, but the benefits they’ve been promised will actually be less than what they’re forced to contribute. They effectively subsidize the benefits of older workers.

The pension crisis also threatens to punish taxpayers with massive, ever-escalating taxes to bail out an unsustainable system.

Twenty years ago pension costs consumed just 3 percent of the budget. Today, one-fourth of the state’s general budget goes to pay for pension costs each year.

Government-worker pensions now consume more than $8 billion in tax dollars annually, siphoning huge amounts of money away from social services for the developmentally disabled, grants for low-income college students and aid to home health care workers.3

Major credit rating agencies, such as Moody’s Investors Service and Fitch Ratings, have taken note of the crowding out. They’ve assigned Illinois the lowest credit rating in the nation – just two notches above junk status.4

And the crowding out will only get worse as pension costs continue to grow.

The status quo cannot continue. Illinois must move away from its broken pension system and toward self-managed retirement plans that the private sector and many states have already embraced.

Skyrocketing benefits have driven pension growth

Critics constantly blame underfunding as the cause of Illinois’ pension crisis. But it’s not.

The real pension problem has been the dramatic growth in benefits granted to government workers over the past three decades.

Benefit costs have risen so drastically that no amount of taxpayer dollars could have kept up with them.

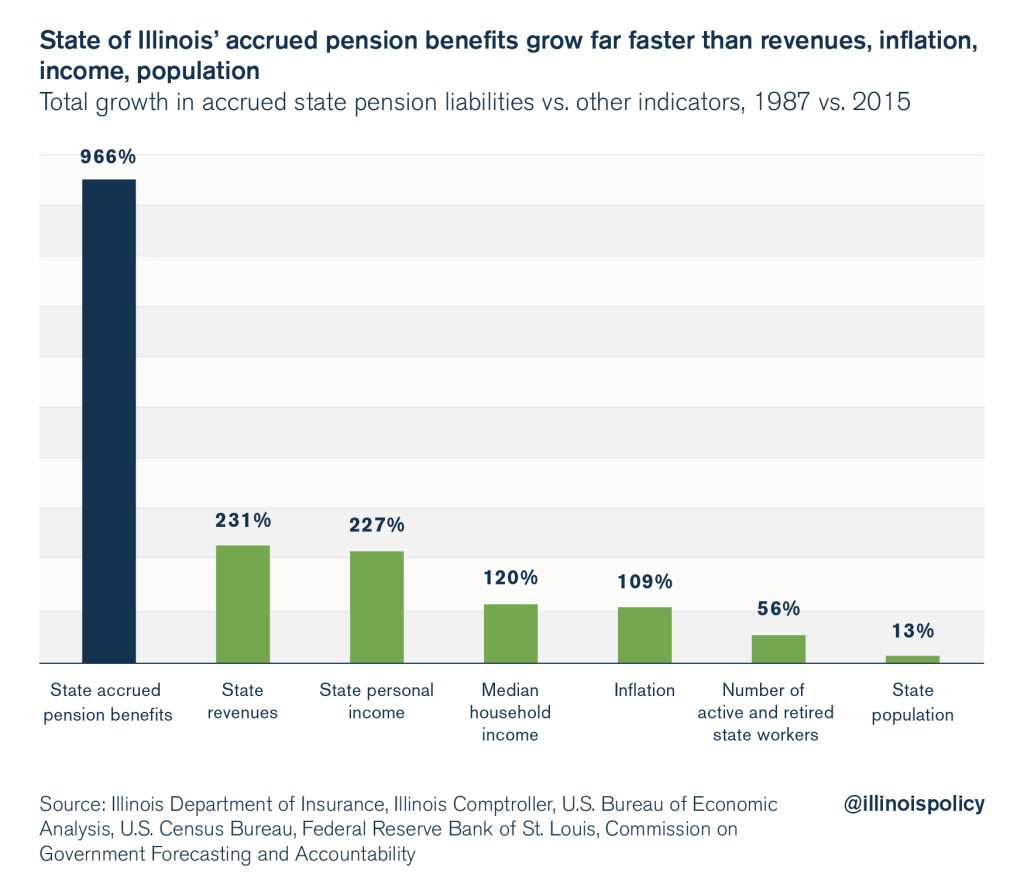

The total benefits owed to workers and retirees (accrued liabilities) have grown nearly 1,000 percent, or nearly 11-fold since 1987.

Then, total benefits owed were just $18 billion. Today, that number totals $191 billion.5

In contrast, the economy has only grown 227 percent; inflation, just 109 percent; and the actual number of participants in the pension systems has grown only 56 percent. The state’s population has increased just 13 percent over that period.6 Pension benefits have grown far faster than any of those factors.

To understand how massive that growth in benefits is, consider that the median Illinois household income in 1987 was $27,000.7

If household incomes had grown at the same rate as accrued pension benefits – 9 percent each year – households today would be making nearly $290,000 a year instead of the $60,400 they take in now.

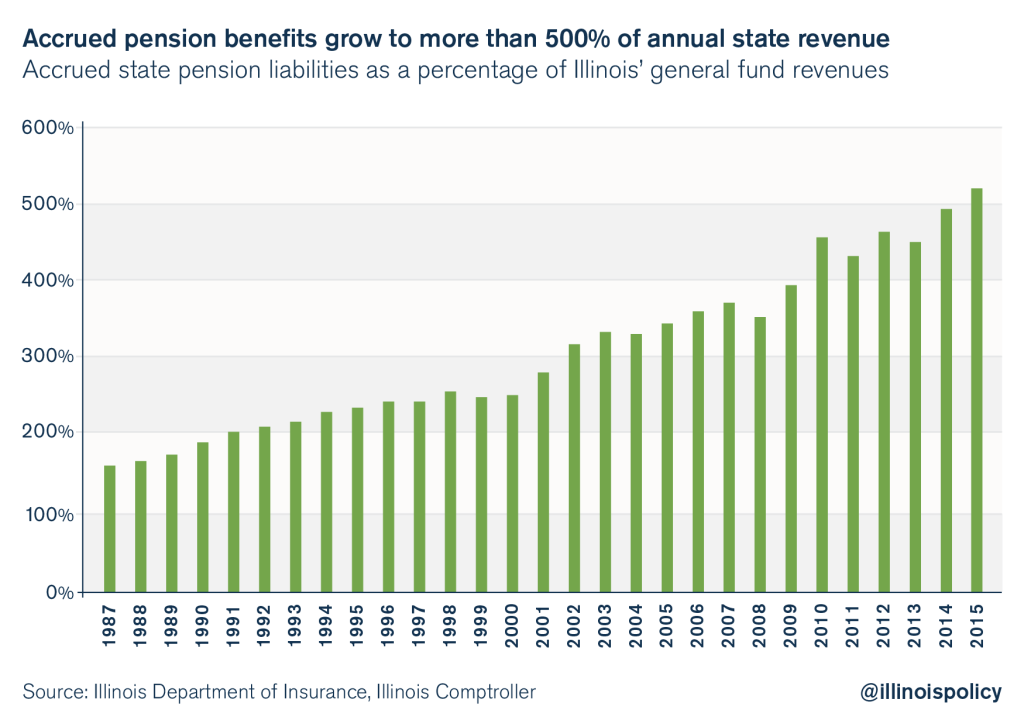

Another way to look at pension benefit growth is to compare it with what the state takes in every year. Accrued pension benefits have grown far faster than state revenues over the past 30 years. In 1987, accrued benefits were just 160 percent of general fund revenues. Now they equal over 500 percent of the state’s general revenue.8

Many critics tend to blame underfunding as the cause of the current crisis, but pension assets – the funding source needed to pay out future obligations – have also grown dramatically over the past 30 years. It’s just that they haven’t managed to keep up with skyrocketing benefits.

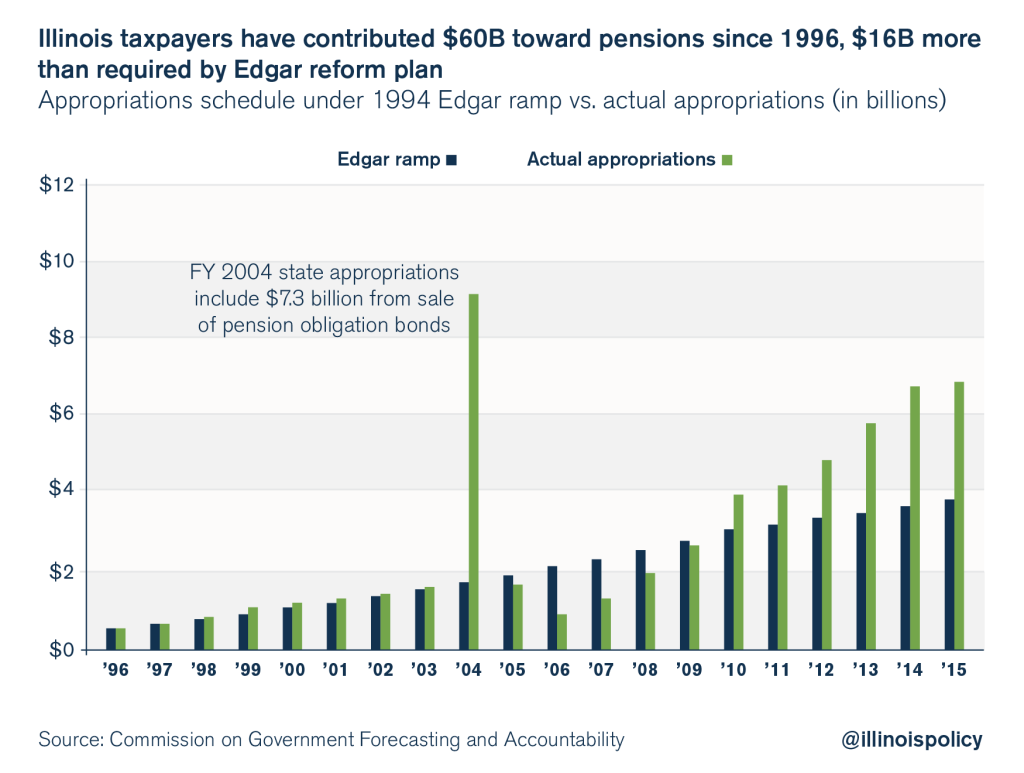

Pension assets grew 627 percent from 1987 to 2015. That’s more than 7 percent per year and also faster than virtually every other metric, with the exception of pension benefits.9 Taxpayers fueled the growth in assets. They contributed nearly $60 billion toward pensions over the last 20 years, $16 billion more than the original 1996 pension reform law called for.

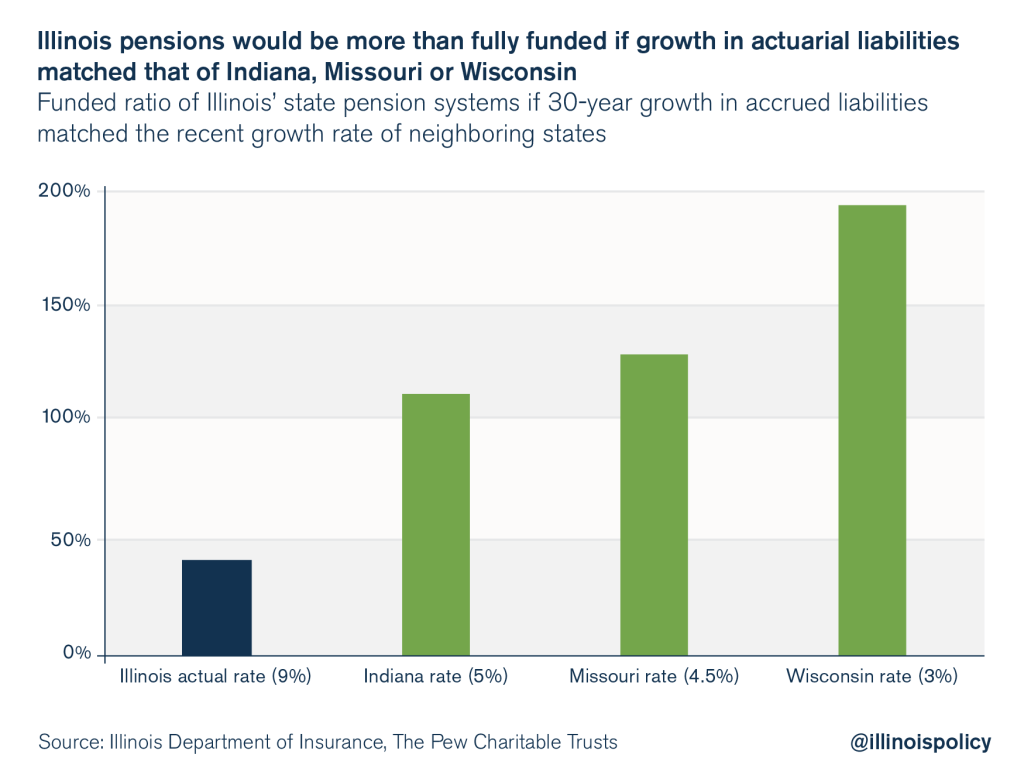

In fact, taxpayers have contributed so much to the system that Illinois would be more than 100 percent funded if accrued pension liabilities had grown at more reasonable rates.

For example, if pension benefits had grown at the more recent pace of those in Indiana and Wisconsin, 5 percent and 3 percent, respectively, Illinois pensions today would be more than fully funded.10 At a 5 percent growth rate, Illinois pensions would be 115 percent funded. With 3 percent growth, they would be funded nearly two times over.

How pension benefits were supercharged

Promised pension benefits haven’t grown at an average rate of 9 percent a year on their own. They’ve skyrocketed because lawmakers and employers have enhanced pension rules and created additional perks for state workers over the past 30 years.

Since 1987, politicians have grown pension obligations through perks11 that:

- Added compounding to a retiree’s 3 percent cost-of-living adjustment

- Increased significantly the pension benefit formulas for the Teachers’ Retirement System, or TRS, and the State Employees’ Retirement System, or SERS

- Provided lucrative early retirement options » Allowed workers to boost their service credit by up to two years using accumulated unpaid sick leave » Granted bigger salary bumps to workers who earn master’s and other graduate degrees

- Allow spiking of end-of-career salaries

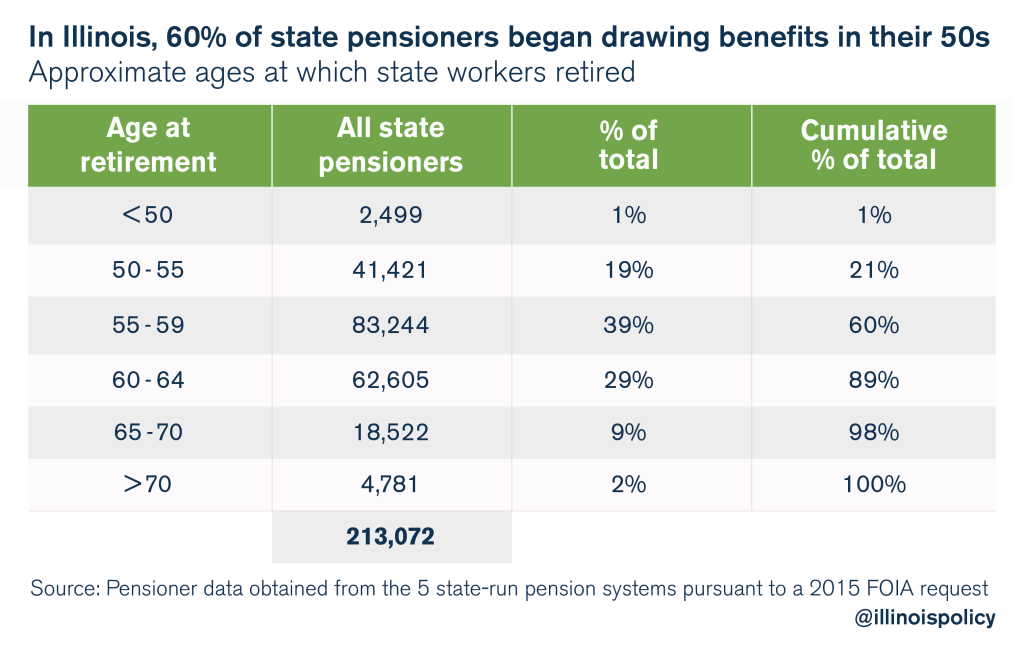

Today, workers’ pension benefits are driven by several major factors: the ability of state workers to retire with full benefits while still in their 50s; automatic 3 percent cost-of-living adjustments that double annual pension benefits after 25 years; and a formula that requires state workers to put in little compared with what they receive in benefits.

Those factors have resulted in the following:12

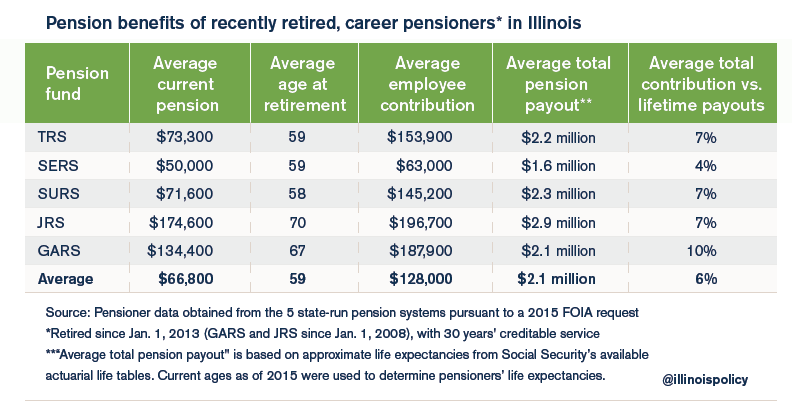

- 60 percent of current state pensioners retired and began drawing pensions in their 50s, many with full benefits.

- The average pensioner who worked 30 years or more receives $66,800 in annual pension benefits and will collect over $2 million in total benefits over the course of his or her retirement (30 percent of recent retirees are career workers).

- The average career pensioner will see his or her pension payments double to more than $130,000 in retirement.

- Career pensioners will get back their employee contributions after just two years in retirement. In all, pensioners’ direct employee contributions will only equal 6 percent of what they will receive in benefits.

The bottom line is this: Pension benefits are too unrealistic for state workers to count on and too rich for taxpayers to pay for.

Pension benefit promises are bankrupting the very pensions retirees count on for their retirement security. And they are unfairly harming the retirements of younger workers.

Younger workers prop up more generous pensions for older workers

The surest proof that benefits reached unsustainable levels came in 2010 when lawmakers enacted a change to the pensions of new state workers.13

Politicians desperately needed a new revenue stream to fund the burgeoning pensions of existing workers. They found that stream in the pension contributions of newly hired state workers.

State workers hired after Jan. 1, 2011, were required to enroll in a substandard pension plan known as Tier 2. That plan forces workers to contribute more to the pension fund than they will actually get out in retirement. New workers actually lose money when saving for retirement.

For example, new TRS employees contribute 9 percent of their annual salary to their pension fund. But the benefits they accrue are only worth 7 percent of their salary annually. They lose 2 percent yearly.14

In contrast, pre-2011 hires also contribute 9 percent of their salaries annually, but the benefits they accrue are worth 22 percent of their annual salary.

A loss for newer workers is a subsidy for pre- 2011 workers. Without that subsidy, Illinois’ pension funds would be collapsing even faster. Unfortunately, the pension system is being propped up on the backs of newer state workers.

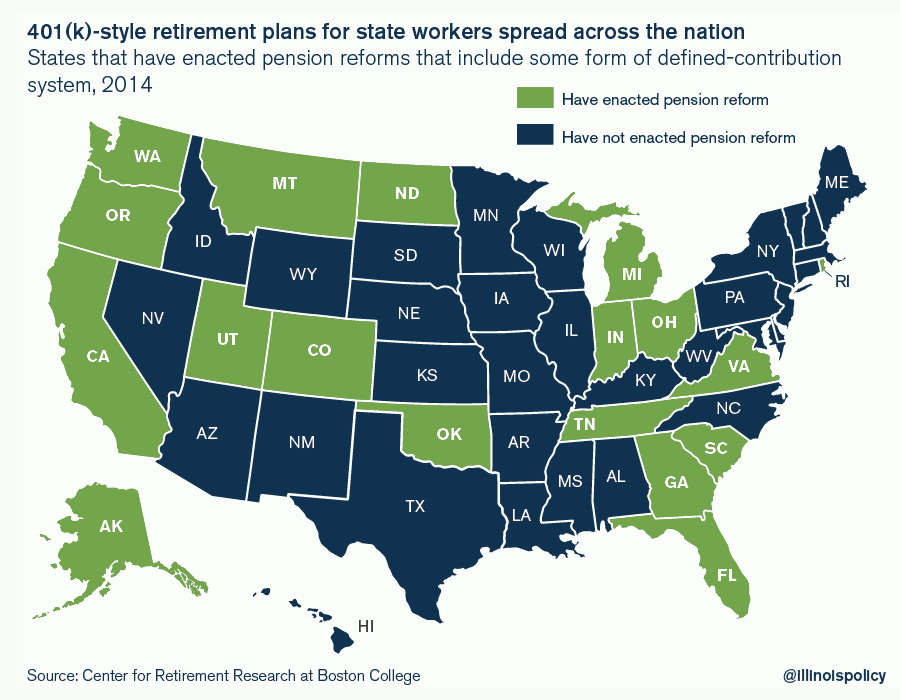

Newer employees should not be asked to sacrifice their retirements to pay for the mistakes of politicians.

The way forward for state workers’ retirements

Illinois’ pension system doesn’t work: not for retirees who are being deprived of a secure retirement; not for younger workers who are forced to subsidize a broken system; not for taxpayers who are being saddled with unaffordable burdens; and not for Illinois’ vulnerable who depend on the state’s social services.

Illinois laid the foundation for a comprehensive transformation of worker retirements in 1998 when it created a self-managed plan, or SMP, for its university workers. The defined-contribution 401(k)-style SMP now has 20,000 active and inactive participants, all of whom control their own retirement accounts.15

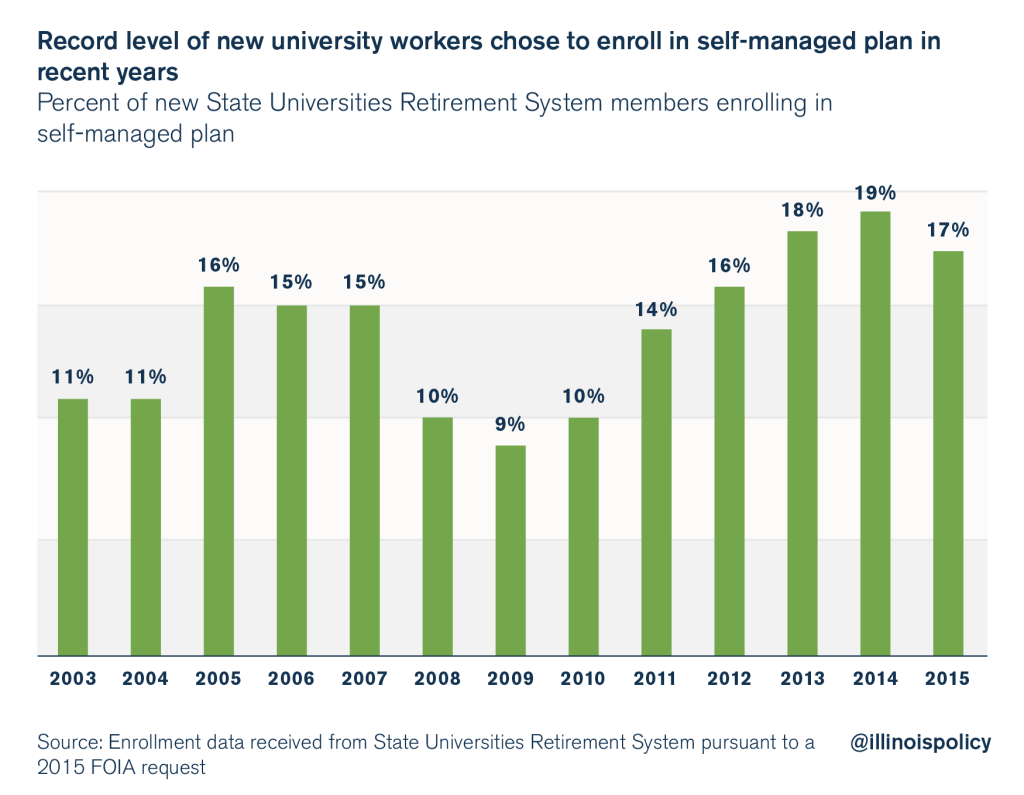

The SMP continues to attract new members every year. In 2014 alone, 19 percent of new university workers chose to enroll in the plan.16

It’s easy to see why. SMP members get to benefit from the current booming market. They don’t have to be concerned about the insolvency of the pension funds. And they don’t have to worry about politicians using workers’ retirement dollars as a slush fund.

Other states have recognized the inherent problems with pensions and have ended their unmanageable and nearly insolvent defined-benefit plans. Over the past two decades, over a dozen states have enacted some form of 401(k)-style defined-contribution plan. Michigan enacted its reforms in 1996, and Alaska passed its in 2005. Even deep-blue Rhode Island passed landmark retirement reform in 2011, which granted workers a hybrid defined-contribution plan. Oklahoma, the latest state to enact reform, moved most new workers into a defined-contribution plan in 2014.17

All these states have followed the lead of the private sector, where nearly 85 percent of workers are now enrolled in some form of defined-contribution plan.18

Illinois must follow in the footsteps of those states and the private sector if it is to end its pension crisis.

The solution: A hybrid retirement plan for state workers

The Illinois Policy Institute’s holistic, constitutional reform plan puts state worker retirements back on a path to financial security. The plan achieves this by creating a mandatory Tier 3 hybrid SMP for new workers and an optional one for current workers. The plan would reduce – and eventually eliminate – the state’s defined-benefit pension plans.

In exchange, state workers would gain true retirement security by controlling and owning their own portable SMPs.

The Institute’s SMP reform would result in a number of valuable benefits for the state, taxpayers, workers and retirees. The plan:

- Respects the Illinois Supreme Court’s 2015 pension ruling by making changes that do not diminish or impair benefits.

- Makes retirement security a top priority for state workers by giving them control and ownership over their own portable SMPs.

- Provides increasingly stable and predictable costs for the state budget going forward.

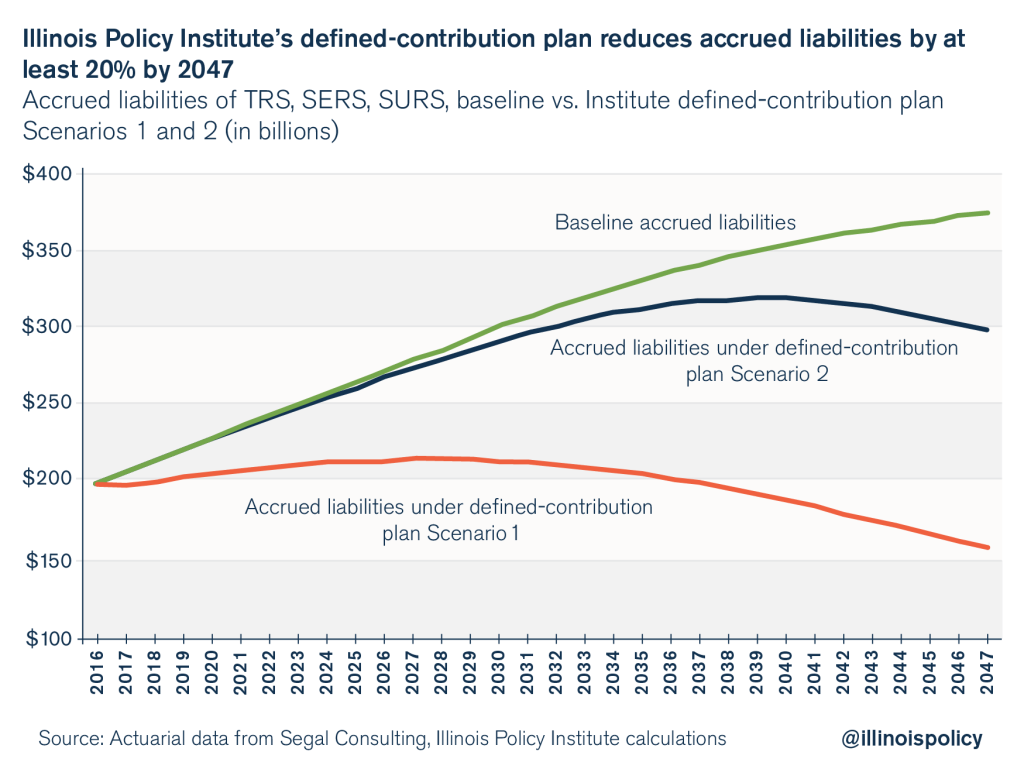

- Significantly reduces the growth in accrued liabilities over time.

- Ends Illinois’ reliance on its broken and nearly bankrupt pension system.

- Enrolls all new workers in a new hybrid SMP. Gives all current workers the option to enroll in that same plan.

- Eliminates the unfair Tier 2 benefit plan going forward and allows existing Tier 2 members to opt in to the new SMP.

- Sends a strong message to the investor and credit agency communities that Illinois is finally tackling its pension crisis.

- Phases in the costs of any pension funds’ actuarial changes over a five-year period. This will reduce the required $800 million increase in state contributions by nearly $650 million in 2018.

- Creates a new contribution schedule with a 2018 payment that is $1 billion less than baseline contributions. That will protect overburdened Illinoisans from tax hikes and allow the state to prioritize funding for social services.

Retirement plan summary

Under the Institute’s pension reform plan, all new workers would be required to enroll in a hybrid SMP, the core of which is based on the State Universities Retirement System’s, or SURS’s, Self-Managed Plan. The hybrid plan contains two key elements: an SMP and an optional, Social Security-like benefit.

All current workers are given the option to enroll in the SMP. If they opt in, their already-earned pension benefits are protected. They stop accruing benefits under the pension plan going forward.

Current workers who do not opt in to the SMP and current retirees would not be affected by the SMP.

Details of the plan

The core of the Institute’s retirement reform proposal is modeled after the defined-contribution-style SMP created for SURS in 1998.19

The SURS SMP’s nearly 20,000 participants control their own retirement accounts.

Under the SURS plan, each employee contributes 8 percent of his or her salary, and the employer contributes an equivalent of 7 percent of the employee’s salary into the employee’s SMP account annually. Participants invest their money with investment service providers that have been chosen by SURS.

SURS’s SMP works well for those who have enrolled, and it continues to attract new members every year. Fifteen to 19 percent of new university workers have chosen to enroll in the SMP in recent years.20

Under the Institute’s retirement plan, new workers and current workers who opt in would own and control a hybrid SMP that contains two key elements: an SMP based on the SURS model and an optional Social Security-like benefit.

The SMP would allow workers access to market returns, while the Social Security-like benefit would provide retirement stability through fixed monthly benefit payments. As with the SURS SMP, state workers would not be allowed to borrow against or withdraw money from their accounts before they retire.

Self-managed plan: Part of the Institute’s hybrid retirement plan for state workers would consist of an SMP. Each worker would contribute a mandatory 8 percent of his or her salary each pay period toward a retirement account he or she both owns and controls.21

The self-managed retirement account would give an employee the opportunity to participate in long-term market returns by investing in a broad range of options vetted by the state. The money in this account would grow over time through accruing employee contributions and investment returns during the employee’s working career.

The self-managed retirement accounts would be portable and transferable from job to job. This would allow state workers to change careers and take their retirement savings with them wherever they go.

When a state worker reaches retirement age, he or she would begin to withdraw funds from his or her self-managed account to provide income. The remaining assets in the account would continue to grow during retirement.

Social Security-like benefit: The other part of the hybrid retirement plan for state workers would consist of an optional Social Security-like benefit. Employers would contribute a matching 7 percent of salary toward their employees’ retirements each pay period. The employer contribution would be used to purchase an annuity-like contract each year from a vetted insurance company. These contracts would provide each employee with a fixed monthly benefit during retirement.

Employees would purchase a new annuity-like contract every year. Each additional contract would add to the total fixed monthly benefit an employee would receive during retirement. Like the self-managed portion, the contracts purchased by the employee would be portable and transferable from job to job.

When state workers reach retirement age, their annuity-like contracts would begin to provide a steady stream of income annually. Because the contracts provide fixed annual payments, much like Social Security, they would provide workers with a retirement safety net independent of the SMP portion of their plan.

If a state worker does not wish to participate in the Social Security-like benefit, the employer’s 7 percent contribution would be deposited into the employee’s self-managed retirement account instead.

Plan membership

The Institute’s plan is designed to end the state’s reliance on pensions by moving all new workers into a Tier 3 hybrid SMP. All current workers – from both Tier 1 and Tier 2 – would also have the option to join the SMP.

Ideally, all current workers would opt in to the SMP right away. That would immediately freeze the defined-benefit system going forward and would result in an immediate end to the accumulation of future pension benefits.

The more likely scenario, however, is that many Tier 1 workers would stay in the current pension plan. Those closer to vesting, for example, have little incentive to leave their current plan.

Younger Tier 1 workers and those who have little to nothing vested in the pension plan, however, might choose to move to the SMP. And others, those with less faith that the pension system will be solvent when it’s their turn to get retirement checks, might also opt in to the SMP.

In contrast, a vast majority of current Tier 2 workers are likely to join the SMP because of the bad pension plan they’re currently under. For them, an SMP option means getting a real retirement plan. In addition, since Tier 2 was started just six years ago, most Tier 2 workers have yet to vest. Tier 2 requires 10 years before an employee is vested in the pension plan. That also makes Tier 2 workers more likely to convert to the SMP.

Plan results

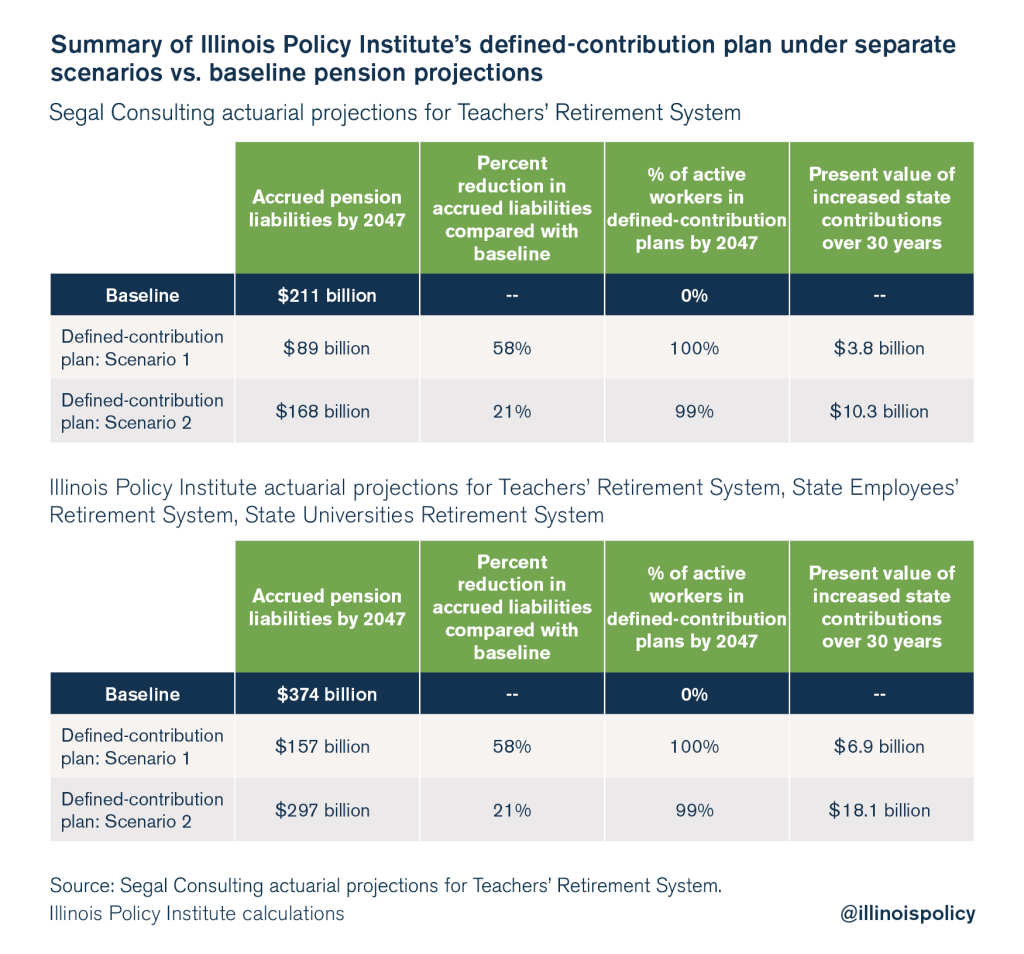

To determine the total benefits and financial impact of eventually ending pensions, the Institute reform plan was analyzed by Segal Consulting, the actuarial firm used by the state for its annual pension analyses.

Segal’s analysis used 2015 data, the most recent data available at the time, and focused on TRS as the proxy for the three major state pension plans.

Those projections were then extrapolated by the Institute to include the impact on SERS and SURS.22

Segal ran two separate scenarios regarding the implementation of the Institute’s plan:

- Scenario 1: Assumes all current workers, both Tier 1 and Tier 2, join the SMP.

- Scenario 2: Assumes only current workers who are members of Tier 2 join the SMP.

Both scenarios achieve a 90 percent funded ratio for the pension systems within 30 years, just as the current pension systems’ funding projections do.

Scenario 1 can be considered the “best case scenario” under the Institute’s SMP. It assumes the unlikely case that all current state workers, in both Tier 1 and Tier 2, will join the optional defined-contribution plan upon its creation.

Scenario 2 can be considered the “worst case scenario” under the Institute’s SMP. It assumes that only current Tier 2 workers will join the defined-contribution plan, even though many younger Tier 1 employees are likely to opt in to the plan.

Scenarios 1 and 2 serve as the two extremes in terms of the financial results of the Institute’s plan. But for the remainder of this analysis, Scenario 2 will serve as the primary comparison. That’s because the Institute’s plan and analysis work even under the worst case scenario.

However, the resulting impact of the SMP improves for every Tier 1 worker who joins the SMP. The reality is participation in the SMP would fall somewhere between Scenarios 1 and 2 (but likely far closer to 2) as some younger Tier 1 workers could be expected to take advantage of the SMP for its portability and access to market returns.

In either case, the Institute’s plan does the following: