New education funding plan repeats Chicago Public Schools bailout history

Senate Bill 1 is yet another unfair bailout of long-term mismanagement within Chicago Public Schools.

After more than a decade of financial mismanagement, Chicago Public Schools is broke and it’s looking for a new state funding formula to bail it out. Enter Senate Bill 1, the education funding bill lawmakers passed in May.

Calling this bill a “Chicago bailout” isn’t empty rhetoric; it’s a sad reality that Illinoisans have seen repeatedly through the years.

The same thing happened in 1995 when CPS was in the midst of a financial crisis. Back then, rather than enact reforms and streamline spending, CPS and the General Assembly worked to change the state education funding formulas in favor of CPS.

Over the next several years, the district benefited from a unique block grant, special subsidies and other carve-outs that were unavailable to most or all other districts.

And then-Mayor Richard M. Daley was given the power to raid the Chicago Teachers’ Pension Fund, or CTPF – nearly fully funded – to hike teacher pay.

Those formula changes and access to the pension fund gave CPS money to burn for two decades.

Now that money has run out, and CPS is insolvent yet again. The district’s credit rating is deeply into junk. Its borrowing costs are crippling. And CPS has nearly lost access to lenders.

That’s why the district – with the support of many legislators – is once again seeking to rig the state’s funding system in CPS’ favor.

At its core, the new funding formula in SB 1 is simply unfair. Districts across the state will be forced to forego additional funding in order to subsidize CPS’ financial mess.

SB 1 would grant additional special treatment to CPS that no other district receives, including:

- The state bails out CPS’ pensions inside of the funding formula. SB 1 requires the state to pay for the annual “normal” cost – the yearly benefits accrued by teachers – as it does for all other districts throughout the state. This will cost the state $215 million annually. But CPS’ pension payment will be the only pension paid for directly through the state aid formula. That arrangement essentially prioritizes Chicago pensions within a fund that is meant to be for classroom and operations funding only. In contrast, the pension costs of all other districts are a separate state expense and a separate appropriation. In addition, CPS will benefit from a “hold harmless” provision, which means no district can receive less funding compared with what it got last year. The state’s pension payment to CPS will be subject to the “hold harmless” provision. This means the $215 million will be locked in even though the district’s normal costs will decline over time due to the lower cost of teachers enrolled in Tier 2 pensions.

- CPS’ pension debt crowds out funding for other districts. The new funding formula also allows the district to receive more money by allowing CPS to appear poorer than it actually is. Currently, CPS has to contribute about $500 million annually to pay down its unfunded pension liability. The new funding formula allows CPS to deduct, or “hide,” the $500 million from the district’s local resources when it applies for state aid. That will make CPS look poorer and therefore eligible for additional state aid. It ensures that CPS is considered a “Tier 1” district, meaning CPS is first in line for new state aid dollars. According to estimates based on Illinois State Board of Education data, CPS will receive about $70 million in additional state aid due to its ability to hide some of its local resources under the funding formula. That subsidy will also grow if CTPF changes its actuarial assumptions. For example, the fund currently assumes its investments will earn a 7.5 percent return. If CTPF lowers that rate to 6.75 percent, as some state funds have done, then its retirement debt cost will grow dramatically.That amount, which is deducted from the district’s available resources, means the district will look even poorer. The result will be an even bigger state subsidy to CPS at the expense of all other districts.

- CPS gets a special $200 million in state funding no other district gets. The funding formula also grandfathers in the money for the unique annual “block grant” CPS has received for 20 years. Now CPS will get both a pension bailout and the money from the block grant. CPS also benefits from the “hold harmless” provision in SB 1 that protects shrinking districts. This provision ensures CPS will not get less money than it does today. That means even if the district’s student population continues to shrink (the district has lost more than 40,000 students since its peak in 2002) or the city’s local resources increase (more skyscrapers in the Loop), CPS will continue to get more money than it deserves.

Rigging the system

This isn’t the first time CPS has gotten itself into a financial mess and forced the rest of the state to bail it out.

In 1995, CPS was near the brink of financial collapse. In response, CPS and Chicago officials – along with the Illinois General Assembly – enacted a series of changes to the state aid formula over the following several years that sent more money to Chicago.

Not only that, but CPS also gained control over its pension fund.

Here are a few of the special privileges CPS continues to enjoy today:

1. Block grant

As part of the 1995 deal, Chicago received a “block grant” for special education, transportation and nutrition programs. While all other districts have to apply for “categorical” aid dollars annually, CPS gets a flat percentage of state aid – all based on its 1997 special student population (special education students, etc.). CPS’ special student populations have declined significantly since then. That means the district is getting more grant money than its special student enrollment would entitle it to. Today, CPS receives about $250 million in additional dollars from the block grant compared with the per capita method all other districts are required to use.

2. Poverty Grant

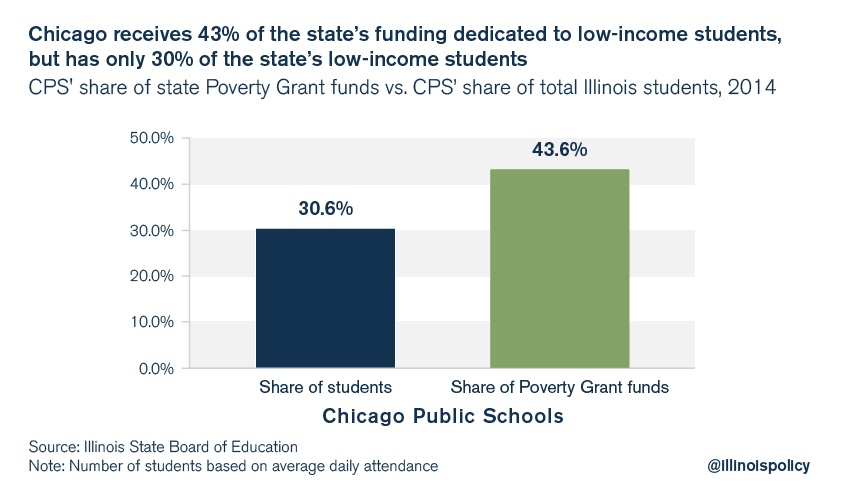

Passed in 1999, a new Poverty Grant formula ensured that CPS would get a larger share of state aid dollars due to its high population of low-income students. Today, over 92 percent of CPS’ student population is considered low-income. The district received about $2,600 in per-student funding for low-income students in 2014, more than 95 percent of all districts in Illinois. In contrast, the average district outside of Chicago receives only $750 in grant funding per student.

In percentage terms, Chicago receives 43 percent of the entire $2 billion Poverty Grant funding even though it only has 30 percent of the state’s low-income students. The rest of Illinois’ school districts are left with little more than half of all Poverty Grant funding, even though those districts have nearly 7 in 10 of the state’s low-income kids.

In percentage terms, Chicago receives 43 percent of the entire $2 billion Poverty Grant funding even though it only has 30 percent of the state’s low-income students. The rest of Illinois’ school districts are left with little more than half of all Poverty Grant funding, even though those districts have nearly 7 in 10 of the state’s low-income kids.

3. PTELL and TIF subsidies

CPS also benefits from a set of subsidies that allows select school districts to look poorer than they actually are. Subsidies were passed in 2000 for school districts whose revenues were negatively affected by both local property tax caps and special economic zones. In both cases, districts are able to underreport their available property wealth when applying for state aid. These subsidies, for Property Tax Extension Limitation Law, or PTELL, and tax increment financing, or TIF, respectively, overwhelmingly benefit CPS. Chicago has a large percentage of the state’s PTELL- and TIF-affected property, so it gets the lion’s share of each subsidy.

Those subsidies have made a big difference in CPS’ funding over the years. For example, in 2009, Chicago received over $500 million in extra state aid thanks to the PTELL subsidy alone.

And in 2011, Chicago received more than $250 million in additional state aid due to the TIF subsidy.

4. Teacher pensions

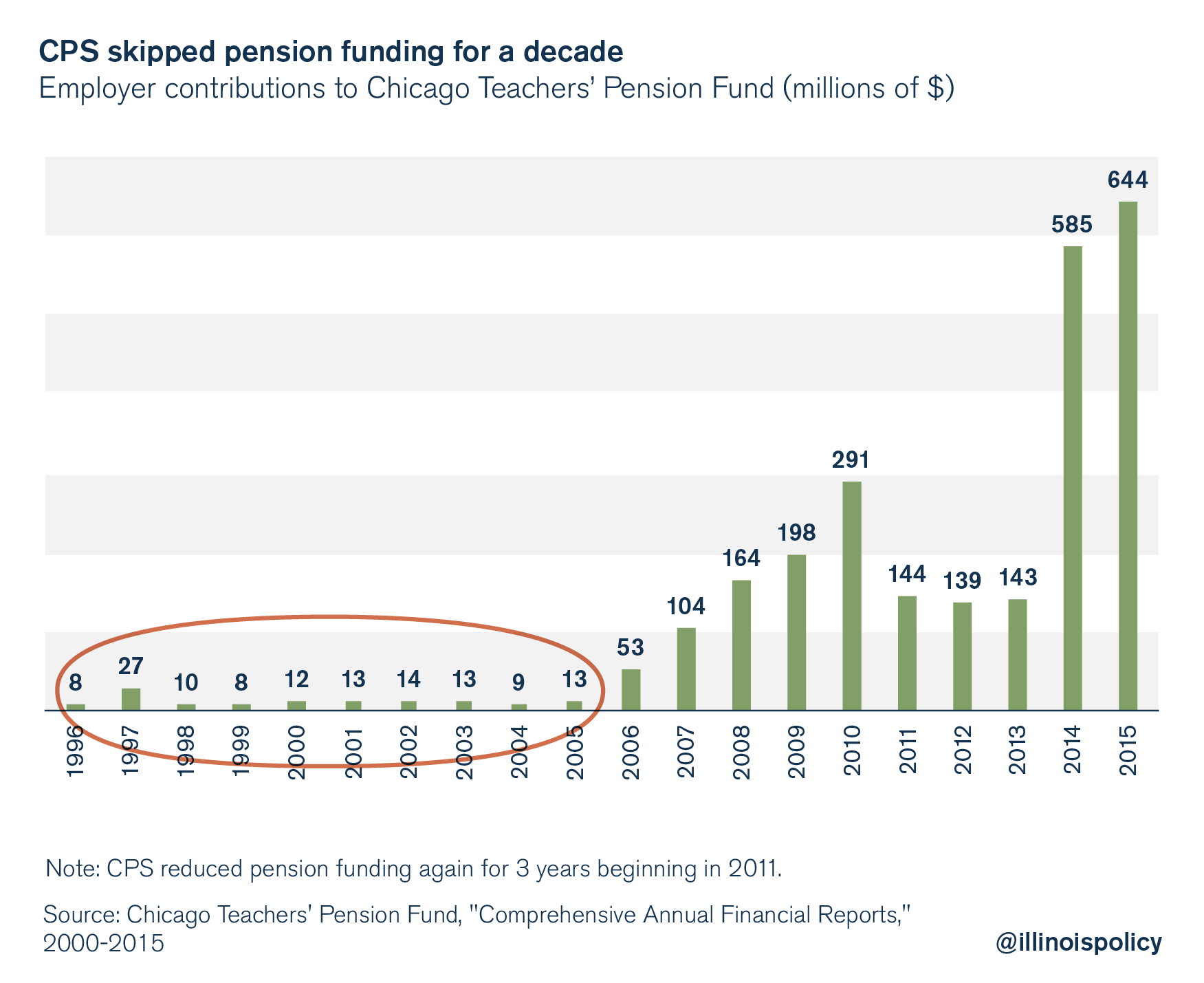

As part of a financial agreement in 1995, state lawmakers agreed to hand over control of the district and the teachers pension fund to then-Mayor Richard M. Daley. Back then, the pension system was approaching 100 percent funded. Daley and CPS officials – with the consent of the Illinois General Assembly – enacted a 10-year pension holiday that diverted at least $1.5 billion away from the pension system and toward school operations and teachers’ salaries.

As teacher salaries rose over the decade, the pension system’s funding began to collapse. The pension crisis grew even worse when CPS enacted another three-year partial holiday from 2011 to 2013.

Mayor Rahm Emanuel, rather than funding pensions or enacting reforms, has added fuel to the fire. In 2012 and 2016, Emanuel gave in to the Chicago Teachers Union’s strike demands and promised teachers even more benefits at the expense of the district’s financial stability.

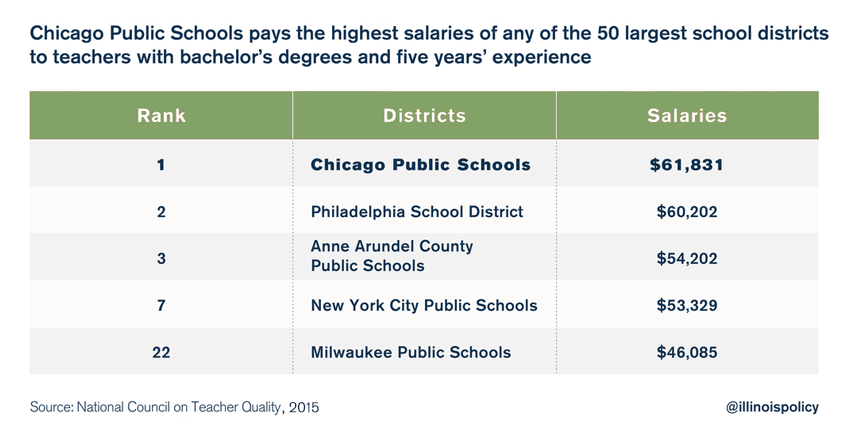

Today, Chicago teachers are the highest-paid in the nation among the country’s biggest school districts. Meanwhile, their pension fund has barely half the money it needs on hand today to pay out benefits.

Don’t bail out CPS

After decades of mismanagement, CPS is broke again. And just like last time, city officials want downstate Illinoisans to bail them out.

Lawmakers should not let history repeat itself. CPS should not be allowed to again rig the funding formulas in its favor with the new education funding bill.

Bailing out CPS’ pensions is a particularly bad idea. In fact, the state should be pursuing the exact opposite course.

Rather than pay CPS’ pensions, the state should stop paying for the pensions of Illinois’ other school districts. Teachers are not state employees. The responsibility for paying the employer’s pension contribution for teachers should be shifted back where it belongs – local school districts.

The current law gives districts incentives to dole out higher pay, end-of-career salary hikes, and perks that spike pensions, knowing the state pays the pension costs. Districts will only moderate the benefits they offer when they are required to bear their own pension costs.

Beyond the CPS bailout, the evidence-based funding model within SB 1 will be an expensive failure – it’s failed to improve student outcomes in the other states where it’s been tried.

If lawmakers want to make sure more education dollars reach students, they should focus instead on freeing up the waste in Illinois’ sprawling, inefficient education bureaucracy.

Reforming expensive pensions, consolidating unnecessary school district bureaucracies and eliminating duplicative administrators are far more effective solutions than an expensive, ineffective new funding formula and a bailout of CPS’ financial recklessness.

For additional reading on Illinois’ education funding formula and evidence-based funding, see the following:

Special report: Illinois education finance solutions

Illinois school district consolidation provides path to efficiency

Understanding Illinois’ broken education funding system

CPS pensions: From retirement security to political slush fund

Evidence-based education funding doesn’t work, would cost Illinois taxpayers billions