Corruption costs Illinois taxpayers at least $550M per year

By Orphe Divounguy, Bryce Hill

Download Report

Corruption costs Illinois taxpayers at least $550M per year

By Orphe Divounguy, Bryce Hill

Download Report

Chicago is the most corrupt city, and Illinois the second-most corrupt state, in the nation, according to a recent report by the University of Illinois at Chicago.

But corruption in Illinois is more than a buzzword. It comes with social and economic costs. Not only does corruption lessen residents’ faith in the government, it decreases economic growth and disincentivizes investments in the state.

Illinois’ public corruption convictions cost the state economy an estimated $550 million every year from 2000-2017, the Illinois Policy Institute estimated according to a 2011 study published in the peer-reviewed academic journal “Public Choice.” That’s a total during those 17 years of more than $9.9 billion.

Federal corruption convictions per capita were 8% more common in Illinois than in other states during that time period.

The annual loss of economic activity means the 285,000 Illinoisans actively seeking employment find it harder to land a job, and the state economy will likely continue to lag the rest of the nation.

Illegal corruption runs rampant

It is no secret that Chicago has a longstanding tradition of political corruption. Now that criminal investigations are threatening to drag in a string of Chicago leaders, it does not look like that tradition is going away anytime soon.

- On June 24, former Chicago Ald. Willie Cochran, 20th Ward, was sentenced to more than a year in prison for wire fraud.

- On June 19, Ald. Carrie Austin, 34th Ward, had her offices raided as part of a corruption investigation.

- In May, Chicago Ald. Ed. Burke, 14th Ward – the city’s longest serving alderman – was indicted on 14 counts of racketeering, attempted extortion, conspiracy to commit extortion and using interstate commerce to facilitate an unlawful activity.

- In 2017, former Chicago Public Schools CEO Barbara Byrd-Bennett was sentenced for a $23 million corruption and kickback scandal.

Corruption in the city of Chicago can be traced back decades and earns the city recognition as the most corrupt in the nation. Federal prosecutors in the judicial district covering Chicago and northern Illinois have obtained 1,731 corruption convictions since 1976.

These figures do not include corruption prosecuted in local courts or crimes that have gone undiscovered. The actions of which Burke has been accused likely have been commonplace for decades in Chicago and stifled the city’s business environment, especially for small businesses, according to a study from the Journal of Business Ethics.

But corruption in Illinois extends beyond Chicago. Four of the past seven Illinois governors have gone to prison. FBI tapes of recorded conversations between Gov. J.B. Pritzker and then-governor, now-federal inmate Rod Blagojevich revealed discussions of a potential appointment of Pritzker to public office and future campaign donations to Blagojevich. And while unrelated to his public office, the governor has come under federal investigation for a scheme to avoid property taxes by taking toilets out of a Gold Coast mansion.

The Blagojevich tapes also include conversations about Illinois House Speaker Mike Madigan. Blagojevich suggested Madigan might be willing to push through Blagojevich’s legislative priorities were he to appoint Madigan’s daughter, then-Illinois Attorney General Lisa Madigan, to the U.S. Senate seat vacated by President Barack Obama.

Madigan’s inner circle is being targeted by federal agents, who are investigating $10,000 in payments to former high-ranking Madigan political aide Kevin Quinn, brother of a Chicago alderman. The payments came after Madigan ousted Quinn from his political organization in 2018 after campaign worker Alaina Hampton accused Quinn of repeated sexual harassment. The Quinn money came from accounts linked to five current or former lobbyists for utility company Commonwealth Edison, including one of Madigan’s closest confidants, according to the Chicago Tribune.

The criminal investigation of Chicago Ald. Danny Solis, 25th Ward, also included recorded conversations between Madigan and a hotel developer who had been directed to Madigan’s law firm by the alderman. While the investigation into Solis hasn’t resulted in any allegations of illegal conduct for the nation’s most powerful House speaker, it highlights another issue with Illinois’ political machine: legal corruption.

What is legal corruption?

Corruption is often defined as using public office for private gain. And while bribes and other criminal tactics garner the most attention, they barely scratch the surface of corruption in Illinois. Legal corruption refers to legal establishments, such as: Chicago’s aldermanic privilege that gives aldermen total control over ward matters; gerrymandering that allows elected officials to draw maps that favor their re-election; procedural rules that give unchecked power to the House speaker; the revolving door between the Statehouse and the lobbying industry; and ethics laws that allow legislators to double as property tax appeals attorneys. Both Madigan’s and Burke’s law firms handle property tax appeals.

Cumbersome and highly restrictive governments such as Illinois’ foster environments where corruption festers.

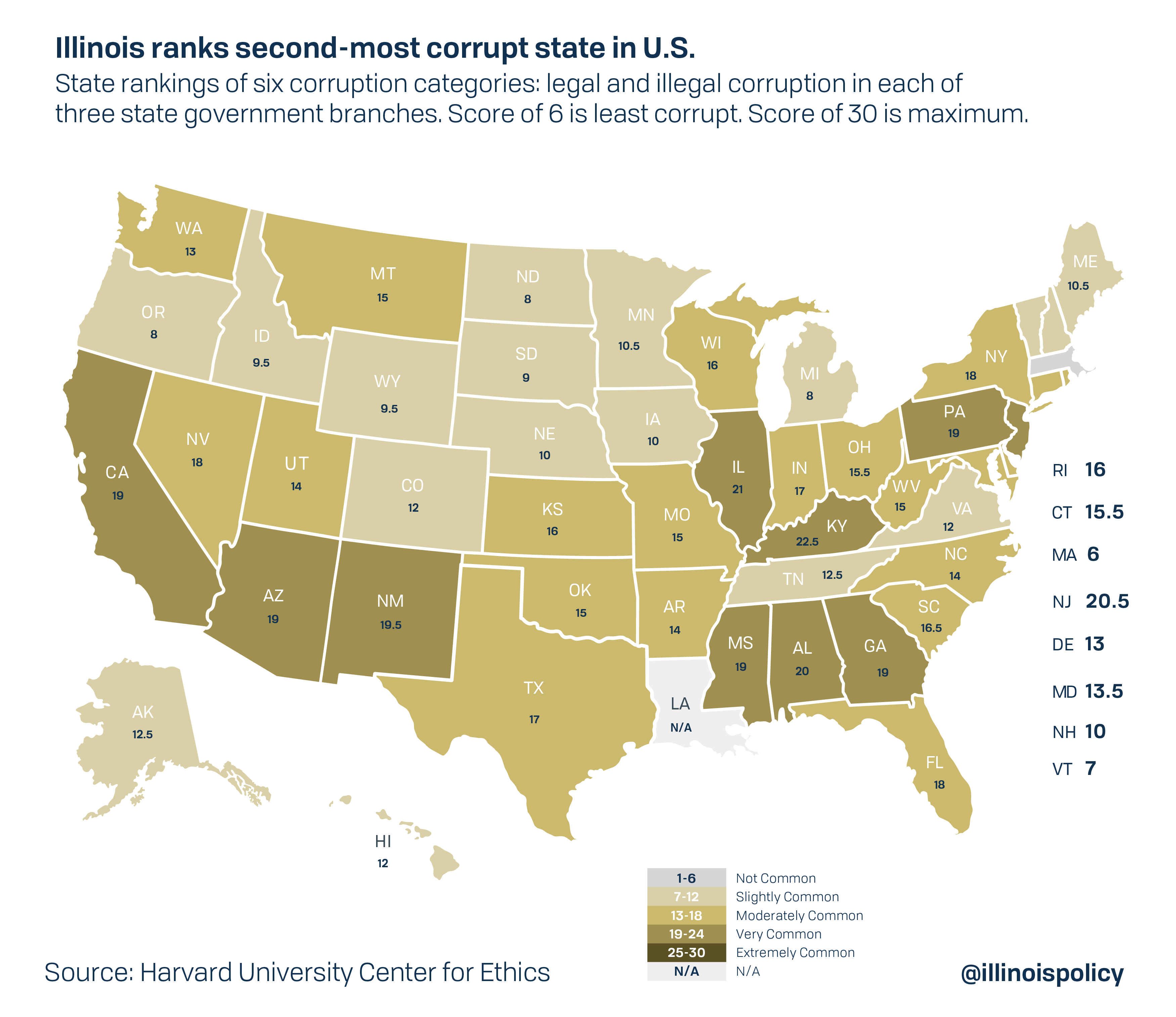

Democrats and Republicans have long engaged in legal corruption such as pay-for-play schemes. Illinois is no exception. According to a study by Harvard University that ranks all U.S. states, excluding Louisiana, Illinois ranks in the top 10 for both legal and illegal corruption.

The study shows Illinois ranks as the second-most corrupt state when all types of corruption are included – both legal and illegal – surpassed only by Kentucky. Beyond individuals who are convicted of corruption-related crimes, Illinois’ executive, legislative and judicial branches all measure in the top 10% of most-corrupt states in the U.S. when evaluated individually.

While some lawmakers use both legal and illegal methods to line their pockets and those of their friends and associates, Illinois residents are seeing fewer job opportunities and a stalling economy.

Economic effects of corruption

Corruption lessens residents’ faith in the government. It decreases economic growth and disincentivizes investments in the state.

While the most observable cost of corruption is bribes, corruption – both legal and illegal – also results in the misuse and misallocation of resources. Illinois’ history with corruption not only reduces the potential for future investments by slowing economic growth, but bolsters the state’s reckless and unethical spending.

Governments that use spending to dispense political favors or to delay permits and licenses also impact the economy, inhibiting individuals from investing and remaining in the state.

Private businesses are often unable to overcome corrupt and burdensome regulator practices, limiting their prospective growth, diminishing productivity and hindering innovation. Entrepreneurs may limit new investments in fixed capital so they can credibly threaten to leave a state should bribe demands become too high. At the same time, uncertainty raises transaction costs above those for a tax of the same magnitude.

Corruption has been directly linked to decreased investments from abroad and slower economic growth. It is no surprise that Illinois is lacking in economic and job growth. States with higher levels of corruption experience higher levels of residents leaving and lower levels of real income per capita, as fewer new firms enter the market and existing firms have less incentive to invest. In a study that compared all 50 states’ gross state products, states with higher levels of convictions for corruption have lower production per worker and slower economic growth.

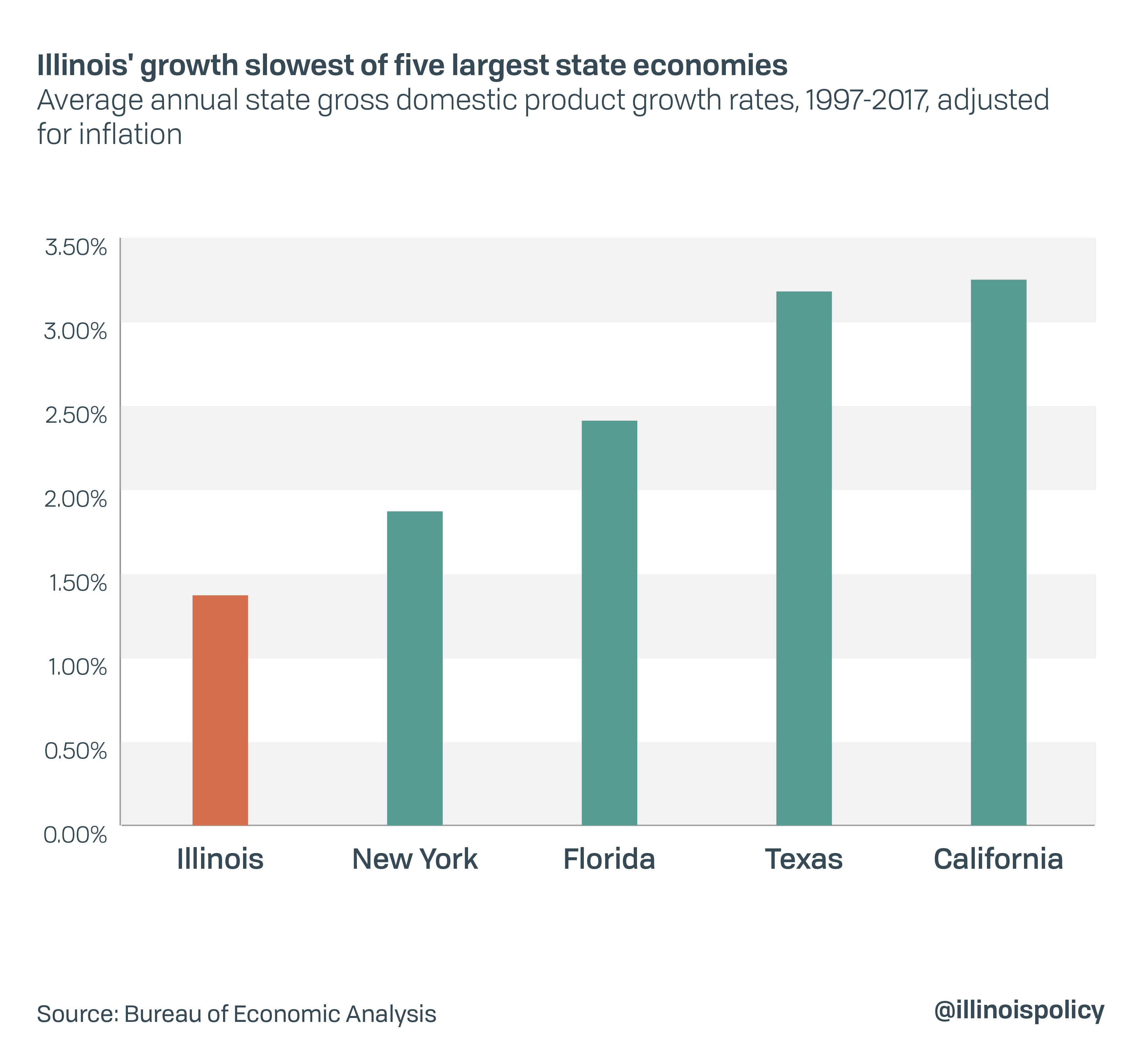

New York, Florida, California and Texas all have lower levels of corruption than Illinois, with Texas having the lowest levels of corruption of the five largest state economies.

Illinois has the slowest economic growth of the five most populous states and the highest level of corruption. As tax burdens increase for Illinois residents and corruption remains prevalent in all levels of Illinois government, Illinois residents will continue to suffer from a sluggish economy compared to other states.

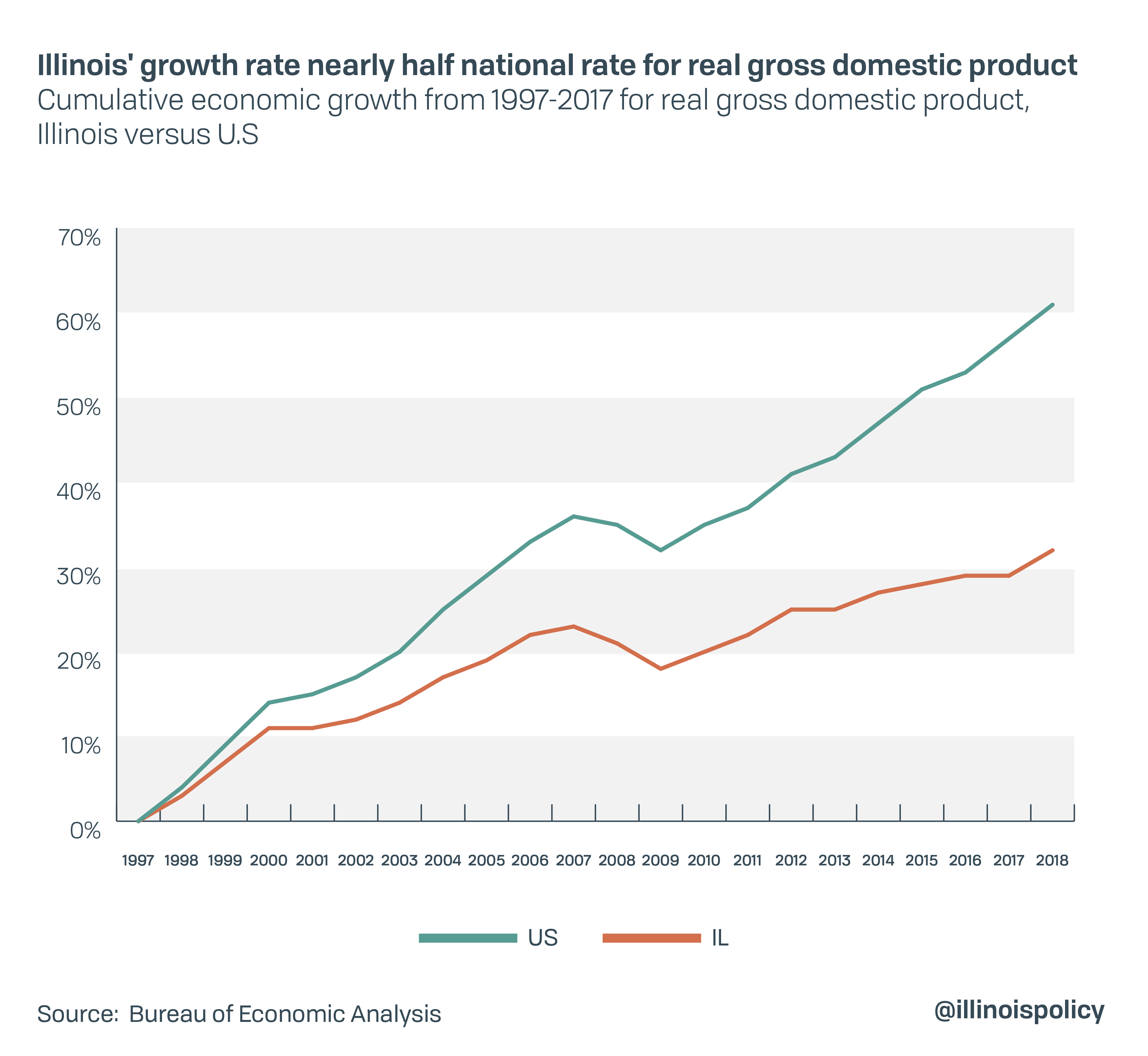

Illinois’ role in the national economy has declined steadily since the 1960s. An economy that was once the third-largest contributor to the nation’s GDP has continued to slip, being passed by Texas and Florida. This shouldn’t come as a surprise, because states with higher levels of corruption on average see lower levels of investment and economic growth. Using data from all 50 states from 1975-2000, corruption was found to play a significant and causal role in reducing economic growth.

To put the findings in context, Illinois’ public corruption convictions cost the state an estimated $550 million every year from 2000-2017.

Illinois ranks 40th in cumulative economic growth, out of 50 states and Washington, D.C., in gross state product from 1997-2018. With real economic growth of just 1.35% annually on average, Illinois trails the U.S. economy with real economic growth of 2.31%.

Meanwhile, the fastest growing state economy in the country, North Dakota, has the lowest level of corruption of all 50 states. Wyoming and South Dakota are also in the top 10 fastest growing economies in the country and both fall in the lowest quartile of corruption by state. States such as Kentucky and New Mexico, the first and fifth most corrupt states respectively, offer a pathetic 36th and 44th ranking in economic growth.

If Illinois wants to break out of its trend of underperformance and compete with the other big-economy states, it could start by doing something about its corruption problem.

Rooting out corruption

Both new Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot and Pritzker need to address the long-standing corruption within the city and the state. For one thing, taxpayers can no longer bear the burden of reckless spending associated with corruption. But also, addressing the problem could lead to job growth and bring economic investment back to the state.

There is some movement in the right direction. Lightfoot’s campaign slogan was, “It’s time to bring in the light.” She has already convinced aldermen to pass ethics reforms and pledged to end aldermanic privilege, which allows aldermen to micromanage the day-to-day activities of businesses and homeowners through power over permitting, zoning and more rather than concerning themselves with citywide policy. As scandals engulf Chicago, aldermen should commit themselves to increased transparency and structural reforms that would change the culture of corruption and focus on governing.

Lightfoot has also advocated for independent ward maps to reduce aldermanic control over the process. But while Pritzker campaigned on a fair maps initiative at the state level, he didn’t touch the policy in his first legislative session.

The governor should also follow Lightfoot’s lead in advocating for legislative reforms. A starting place would be to ask state lawmakers to reform the legislative process to allow for bills to more easily move out of the Rules Committee, improving the legislative calendar so that lawmakers know when bills will be discussed and limiting the ability of the House Speaker to substitute lawmakers in and out of a committee, which can alter the result of the committee vote.

Pritzker should also advocate for tighter ethics laws. Illinois is currently considered one of the worst states when it comes to laws inhibiting a revolving door of lawmakers becoming lobbyists. Furthermore, in April 2019, former Legislative Inspector General Julie Porter criticized the structure of her former office, which investigates potential ethical issues within the General Assembly. Because the inspector general can be denied the ability to open an investigation by the legislative ethics commission, Porter stated, “Unless and until the legislature changes the structure and rules governing the LIG, it is a powerless role, and no LIG – no matter how qualified, hardworking and persistent – can effectively serve the public.” Leaders should empower Illinois’ top lawmaker watchdog to provide basic oversight.

The governor could also borrow initiatives from previous General Assemblies, such as barring legislative leaders from acting as party chairperson and banning state and local lawmakers from participating in property tax appeals cases.

Pritzker should follow the lead of his fellow freshman executive, but both he and Lightfoot must do more to reduce the harmful effects of Illinois’ political machine. Curbing both legal and illegal corruption is an important step in ensuring that families and businesses feel secure to invest in Illinois.