With federal investigators circling and growing calls for his resignation among members of his own Democratic party, Illinois House Speaker Michael Madigan’s days at the height of political power may be coming to an end. A post-Madigan Illinois presents an opportunity to undo decades of corruption and financial mismanagement that stem from his rule.

Madigan became the longest-serving statehouse speaker in United States history in August 2017. Save for two years when the Republicans held a majority in the House, he’s held that position since 1983. Madigan has also been the chairman of the Democratic Party of Illinois since 1998. These dual roles have enabled Madigan to establish near-monopolistic power over public policy creation in Illinois.

No other person in Illinois, or any other state, has had as much influence over both elections and official legislative power as Madigan during the past several decades. The rules of the Illinois House give the speaker the power to appoint committee chairs, swap committee members at will ahead of important votes, and single-handedly decide when – and even whether – bills get called for a vote.

Madigan has used his power to build unprecedented levels of state debt, primarily by helping secure for politicians and public union workers generous retirement benefits that have proved unaffordable for the private sector workers and businesses who fund Illinois government. In return, union leaders are one of Madigan’s chief special-interest allies and political funders.

The results for Illinoisans have been disastrous.

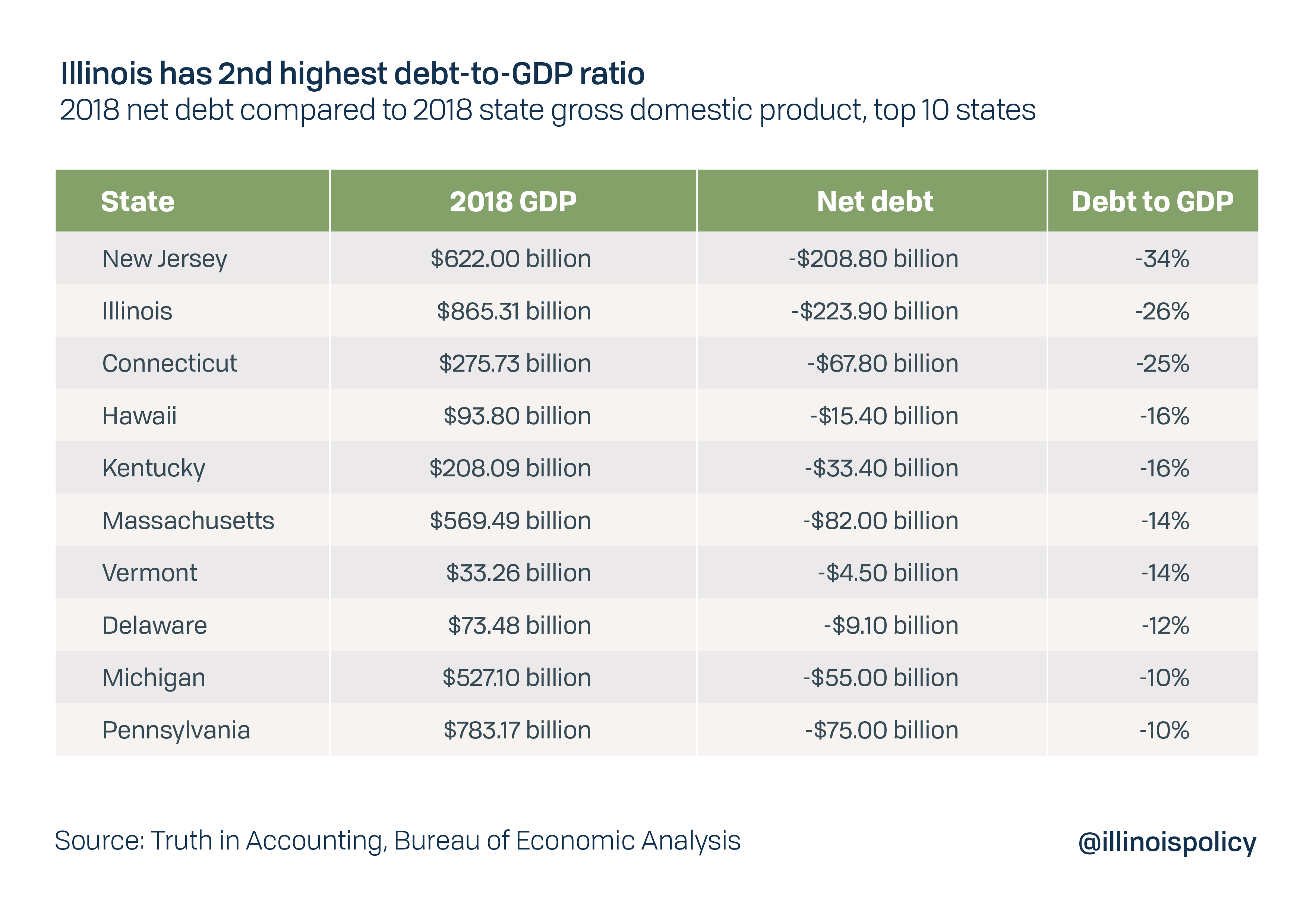

Today, Illinois holds the nation’s lowest credit rating from all three major ratings agencies – just one notch above non-investment grade junk status and the lowest of any state in U.S. history. It ranks as at least the sixth-highest taxed state, the second-most indebted and the second-most corrupt.

These three problems – high taxes and debt combined with low levels of public trust resulting from corruption – have in turn resulted in consistently poor economic performance and an exodus of Illinois residents to better-run states.

The recent FBI probe into Commonwealth Edison’s bribery scheme, in which it admitted to offering patronage jobs and various other payments to the speaker’s allies in return for his backing of favorable legislation, reminds Illinoisans they also pay a price for Madigan’s culture of corruption. According to research from the Illinois Policy Institute, corruption costs Illinois’ economy an estimated $556 million per year, for a total of nearly $10.6 billion from 2000 to 2018.

Just ending Madigan’s reign will not solve these problems. Illinois must also implement targeted reforms to unravel the web of systemic mismanagement and corruption he’s created, including:

- Reform the House Rules to spread power more evenly through its membership

- Implement budget process reform, such as a spending cap and strengthening the balanced budget requirement, to encourage fiscal responsibility

- Amend the Illinois Constitution and implement true pension reform, fixing once and for all Illinois’ most daunting public policy challenge and erasing the most glaring example of Madigan’s legacy of failure

With these three policy changes, Illinoisans can begin to responsibly eliminate Madigan’s mountain of debt and begin a more prosperous future.

Madigan’s rise to power and Illinois’ declining fiscal health

In a Reuter’s special report, “The man behind the fiscal fiasco in Illinois,” long-time Illinois reporter Dave McKinney wrote, “Hundreds of politicians share blame for drowning the state’s government in billions of dollars of debt and unfunded pension liabilities. But House Speaker Michael Madigan – a dominant political force for three decades – has been the constant in key decisions that created the mess.”

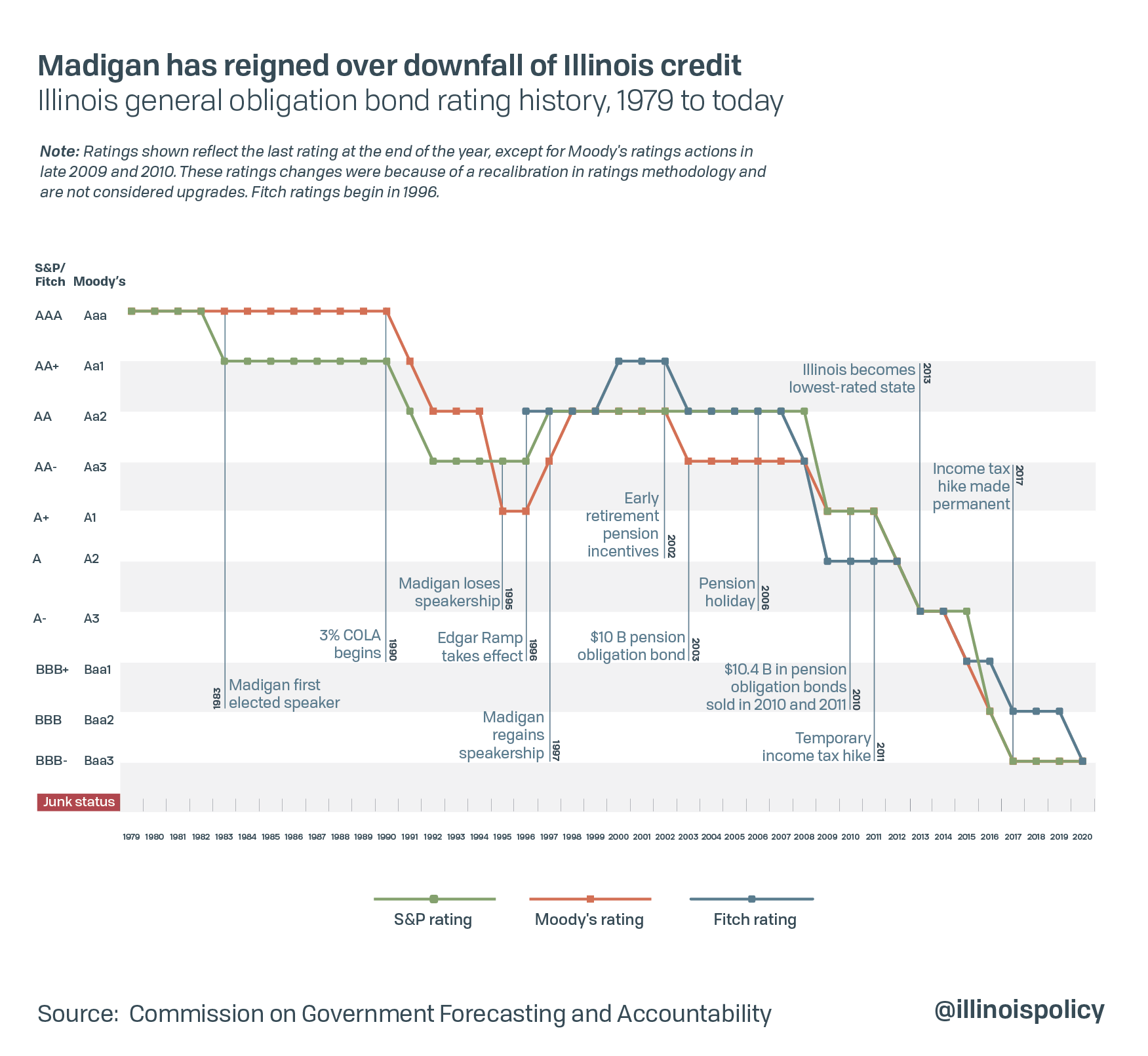

Indeed, Madigan’s fingerprints can be seen on virtually every major piece of legislation that laid the foundation for Illinois’ credit rating fall. Credit ratings represent an expert assessment of a state’s overall fiscal health and ability to repay debt. Lower credit ratings increase the cost of borrowing to taxpayers, because bond buyers demand a premium for higher-risk debt.

Before Madigan became speaker in 1983, Illinois held the highest possible credit rating from both S&P Global Ratings and Moody’s Investors Service. Fitch Ratings issued its first Illinois rating in 1996.

The state’s first S&P downgrade occurred in 1983, the same year Madigan became speaker. The first downgrade from Moody’s and second from S&P came in 1991, the year after the start of major pension benefit increases, including a 3% compounding increase in retirees’ benefits and special perks for politicians’ pensions. According to Chicago Tribune reporting at the time, the 1991 downgrades resulted from the failure of the state to balance its budget that year without short term borrowing.

Illinois’ poor credit reflects its immense debt, second only to New Jersey’s – relative to the size of each state’s economy.

Pension debt accounts for more than 55% of Illinois’ total debt while unfunded retiree health insurance debt accounts for another 22%, according to figures from Truth in Accounting. That means retirement benefits for public workers account for more than 77% of the state’s total debt burden. Looking at pension debt alone, Illinois’ pension crisis is the worst in the nation measured by the state’s debt-to-revenue ratio.

Madigan owns that debt more than any other politician. While various governors and other elected officials have played key roles, Madigan has been the sponsor of major contributing legislation or the gatekeeper allowing bad bills to pass at every step along the way.

Combined pension debt of the five state retirement systems has grown from $5.94 billion in 1982 to nearly $140 billion today. That’s a 753% increase after adjusting for inflation.

In fact, though the speaker is not named, the 2013 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report from the state of Illinois notes there has been a “dramatic increase in debt service payments and outstanding debt since fiscal year 1980.” It’s no coincidence that Illinois’ addiction to debt began around the same time Madigan rose to power.

Why Madigan owns the nation’s worst pension crisis more than anyone else

A Crain’s Chicago Business exposé on how Illinois ended up with the nation’s worst pension crisis notes that Madigan “has been involved with every major pension bill of the last 30 years.” In fact, Madigan’s involvement now stretches back more than 40 years, to what many would consider the foundational mistake of the state’s pension system.

The pension clause

Before he was first elected to the Illinois House in 1971, Madigan was a delegate to the 1970 constitutional convention and voted in favor of the pension clause, which states that government employee retirement benefits shall not be “diminished or impaired.”

The Illinois Supreme Court essentially ruled in 2015 that this clause prevents any meaningful reform without a constitutional amendment. Once a benefit enhancement is offered to a worker, it can never be modified for sustainability or affordability, even for future work. The clause not only prevents cuts to benefits earned for past service, but also guarantees that an employee will continue earning new benefits under the same formula in place on the day he or she was hired. Effectively, this one clause in the 1970 constitution has put generations of Illinois taxpayers in fiscal handcuffs.

At the time, delegate John Parkhurst of Peoria warned against the pension clause. “This is a terribly, terribly mischievous amendment,” he said. “It is the desire of a special interest group; it should be legislative; there is no history of impairment; there is no history of welching on any contracts; and to put it in the constitution is simply pandering to a group that haven’t been able to have their way in the General Assembly.”

Another delegate, history professor George Cullom Davis, raised the issue of whether the convention should be enshrining such protections in the constitution without checking with the expert pension forecaster employed by the state, “I think that we would be making a serious mistake to adopt this language without consulting at least with the actuary who advises the Pension Laws Commission of the state.”

Opponents’ arguments fell and the pension clause passed. In the decades that followed, Madigan repeatedly supported legislation to enhance pension benefits that would be locked in place by the pension clause once granted. Many times, he did so without a cost estimate or analysis from a professional actuary, just as had been done in 1970.

Automatic retirement raises and perks for politicians, without a price tag

In 1989, Madigan was a House sponsor for Senate Bill 95, which passed without an actuarial cost estimate. The bill was the start of 3% compounding benefit increases for retirees in Illinois’ pension systems. Unlike a true cost-of-living adjustment, these guaranteed increases are not tied to the general price level or inflation.

Additionally, the bill provided state politicians with unique perks enabling them to spike their pensions late in their careers.

For members of the General Assembly, the bill for the first time offered an extra 3% of the originally calculated pension for each year worked after 20 years of service. This perk boosted the pension of Democratic state Sen. Emil Jones, the chief sponsor, by $41,000 annually. It also enabled former Senate President John Cullerton to retire with a pension that will spike to $128,000 just a couple years into retirement and be worth more than $2 million during the course of his retirement. That perk ended for lawmakers elected after 2003, but will still be available to Madigan himself.

The late former Gov. James Thompson, who signed the legislation, also got a special pension boost. The Chicago Tribune reports the law enabled the governor to swap his service credit from the State Employees Retirement System to the more generous General Assembly Retirement System, GARS, without paying the fair cost of the difference in benefits. A second bill Thompson signed in 1991 spiked his pension further by removing a cap on his pensionable salary. GARS is now the worst-funded of the state pension plans with just 16% of the money on hand needed to pay future promised benefits. Bills that enhanced politicians’ pensions at taxpayer cost are the main culprits.

In 2002, Madigan sponsored an early retirement plan promoted by former Gov. George Ryan that allowed more than 11,000 state employees to retire as early as age 50 with full pension benefits. Crain’s Chicago Business reports the early retirement perk cost taxpayers $2.3 billion. In effect, the perk was a golden parachute for Republican-appointed employees who wanted to cash out before Democratic Gov. Rod Blagojevich took office.

Reforms to roll back some of these irresponsible decisions would go a long way toward solving Illinois’ fiscal crisis. Original actuarial analysis of a plan developed by the Illinois Policy Institute found that fixing the automatic cost-of-living allowance alone could eliminate more than 11% of the state’s pension debt. These savings are possible through temporary, targeted COLA freezes to allow inflation to catch up to past benefit increases as well as through replacing the 3% guaranteed compounding raise with a true COLA tied to inflation.

In addition to supporting benefit increases the state couldn’t afford, Madigan has also been at the center of pension funding games that deferred costs to the future.

Accounting gimmicks to hide enormous costs

In 1994, Madigan helped Republican Gov. Jim Edgar pass the infamous pension funding plan known as the “Edgar Ramp.” That plan locked underfunding into Illinois law by setting a target of 90% funding by 2045, rather than the 100% recommended by actuaries. The funding period was also too long and it was backloaded, lowering payments for the years Edgar was in office and raising them dramatically for his successors. The plan included no reforms to ensure the lower payments were sufficient to cover the pension debt the state accrued each year.

Madigan backed the plan in the midst of Edgar’s campaign for a second term as governor, surprising Democratic candidate Dawn Clark Netsch, who had planned to use inaction on the pension crisis against the sitting governor, according to Reuters. Madigan had backed Netsch’s opponent in the Democratic primary, and according to Edgar, was looking to protect his House majority in what was a wave year for Republicans.

The next two years marked the only time Madigan did not serve as Illinois speaker since 1983, after he lost his Democratic majority in the House.

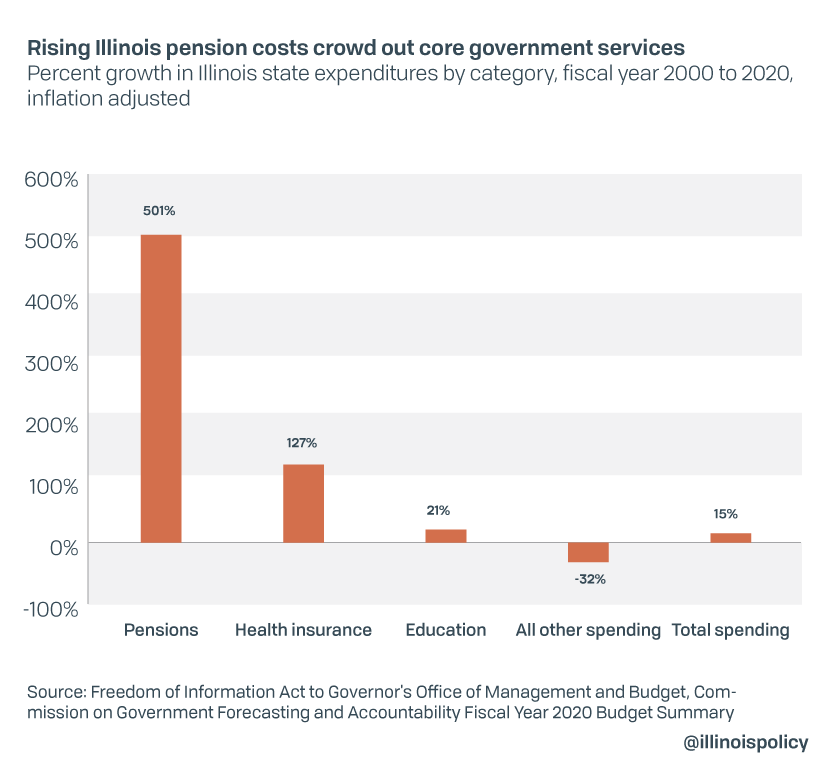

Pension contributions accounted for less than 4% of Illinois’ general funds budget from 1990 through 1997, but under the Edgar Ramp have grown to consume more than 25% of the budget in recent years. Since the year 2000, pension costs have increased by more than 500% after adjusting for inflation while spending on all other services, including services for the poor and disadvantaged, have fallen by nearly one-third.

But the Edgar Ramp was not the last time Madigan would participate in dangerous funding games and hand out unaffordable pension enhancements.

After Madigan’s deal with Ryan to give generous early retirement packages to thousands of public employees, the speaker worked with Blagojevich to swap pension debt with $10 billion in bond debt. That borrowing had the support of politically active public unions, including the Service Employees International Union, the Illinois Federation of Teachers and the Illinois Education Association. The $10 billion bond issuance will cost taxpayers nearly $22 billion in total and won’t be fully paid off until 2033.

The bond proceeds were used as an excuse for “pension holidays” that reduced pension contributions by more than $1 billion each in fiscal years 2006 and 2007. Blagojevich and other proponents of the plan argued the cash infusion from the 2003 pension bond sale justified lower regular annual contributions from the budget. However, those deposits simply swapped a debt to the pension funds with a debt to the bond holders – a debt that still must be paid out of future revenues. The Blagojevich pension holidays are now widely recognized for deepening the pension debt.

As the state’s leading Democrat and speaker of the House – empowered by procedural rules granting him immense individual power to decide which bills pass and which fail – Madigan was closely involved with each of these bad decisions that laid the groundwork for Illinois’ worst-in-the-nation pension crisis.

Avoiding necessary reforms

While the speaker was supportive of an effort to fix the pension system with structural reforms in 2013, and was a sponsor of reform legislation in the House, that effort was ruled unconstitutional by the Illinois Supreme Court in 2015. Since then, Madigan has made no serious effort to fix the pension mess he was instrumental in creating.

A proposed constitutional amendment that would clear the way for reforms similar to those passed in 2013 was bottled up in the House Rules Committee by the speaker in 2019 and again in 2020, preventing it from being debated or voted on.

Madigan created a Springfield culture of supporting unaffordable benefit enhancements without reliable cost estimates and then financing those benefits with debt rather than responsible funding plans. The resulting pension crisis is the chief cause of Illinois’ high taxes, poor credit and inability to fund core government services.

Unfortunately, that culture continues today. In December 2019, Gov. J.B. Pritzker signed legislation supported by Madigan which enhanced benefits for employees hired after 2011 without an actuarial cost estimate.

How Madigan’s concentrated political power institutionalized bad budgeting practices

Just as he owns the pension crisis, Madigan is largely responsible for Illinois’ decades of institutionalized budget mismanagement. In 2018, a study by the Mercatus Center at George Mason University ranked Illinois as having the worst overall fiscal health of any U.S. state.

Madigan is famous for the control he exerts over the annual budget-making process. In 2016, political blogger Rich Miller wrote in CapitolFax that “Senate Democrats are tired of being forced to vote for a House budget for the umpteenth time.” He was referencing a common Madigan tactic, in which the speaker refuses to take up budget legislation directly from either the governor’s office or the Illinois Senate.

Instead, Madigan prefers to wait to release his own budget language at the last possible moment, forcing state senators and governors alike to respond to his demands. Often, Illinois residents and watchdog groups do not have time to review the budget before it’s passed. For example, the 1,245-page 2018 budget was made public less than five hours before lawmakers cast their votes.

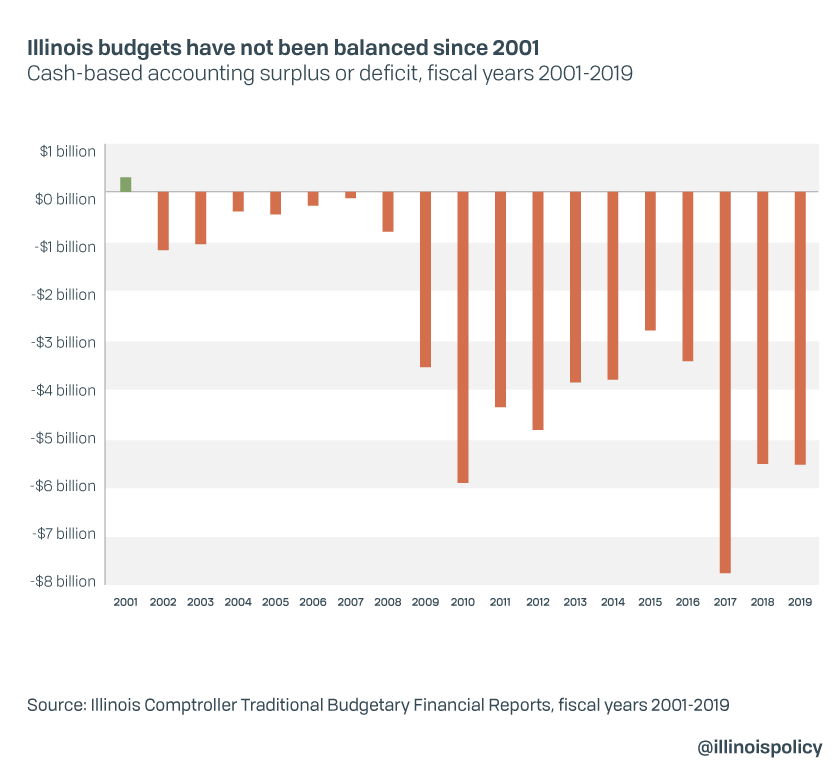

The state has not ended a fiscal year with a balanced budget since fiscal year 2001.

Pritzker and Madigan’s latest budget for fiscal year 2021 has a nearly $6 billion deficit that is partially covered by borrowing and gimmicks.

Although the state constitution includes a balanced budget requirement, it is essentially toothless and can be circumvented using budget gimmicks on which Madigan’s majority has frequently relied.

The constitution reads: “The General Assembly by law shall make appropriations for all expenditures of public funds by the State. Appropriations for a fiscal year shall not exceed funds estimated by the General Assembly to be available during that year.”

The word “estimated” is the problem because it applies only to budget planning. It does not require the budget to actually balance at the end of the fiscal year. Lawmakers frequently overestimate revenue, underestimate expenditures, or count on debt and money moved from other state funds as sources of “revenue.”

Additionally, Madigan’s budgets frequently sweep money from the state’s “rainy day” fund to cover ordinary operations spending. Because this money is used for non-emergency purposes during good economic times, Illinois lacks a functioning emergency savings account when recessions or other disasters strike. The state had essentially nothing set aside to help manage the COVID-19 pandemic that struck in March 2020, for example.

An Illinois Policy Institute report, “Bad budgeting basics: How Illinois’ budget process hurts taxpayers,” details how these gimmicks have helped paper over significant deficits and enabled overspending by Springfield politicians.

Among the report’s findings:

Illinois ranked 45th among U.S. states for rainy-day fund reserves from 2005 to 2018, saving just 0.8% of its budget compared to an average of 4.6% for all states. Experts generally recommend states hold 5-10% of annual revenues in reserve to prevent policymakers from having to rely on severe service cuts or tax hikes during recessions and disasters.

- From 2003 to 2017 the state budget included nearly $38 billion in inadvisable budget maneuvers, each year relying on one-time revenue infusions from borrowing and special funds transfers to cover operating deficits.

- Illinois is one of just 11 states lacking a “true” balanced budget requirement, in which revenues and expenditures must balance at the end of the fiscal year rather than just in lawmakers’ projections.

If current federal investigations or backlash from other Democrats lead to Madigan’s ouster, lawmakers should also look to unravel the systemically dysfunctional budget process the next speaker will inherit.

Reforms for a prosperous, post-Madigan Illinois

Madigan’s fiscal legacy is a mountain of debt and high taxes that harm Illinois’ economy and drive away its residents.

Illinois lost more than 850,000 residents during the past decade and has seen overall population loss for six years running. The most common reason residents give for wanting to leave is the high tax burden, according to public opinion polling conducted for NPR and the University of Illinois-Springfield. Analysis from the Illinois Policy Institute has uncovered a weak housing market and poor job opportunities as other core causes of the exodus, which are linked to the tax burden.

The prospect of a post-Madigan Illinois offers an opportunity to reverse these worrying trends. Making the Prairie State a desirable destination for workers and businesses will require policy reforms that begin to undo the speaker’s bleak legacy.

The Illinois Policy Institute early this year released a comprehensive plan for a prosperous future, “Illinois Forward: A five-year plan for balanced budgets, declining debt and tax relief.”

First and foremost, Illinois should amend its constitution and pursue significant benefit reforms to make pensions affordable and sustainable. A “hold harmless” plan that protects already-earned benefits but reforms benefit growth going forward can save billions for the budget, put the state on a sustainable path to eliminate pension debt, free up resources for investment in services for poor and disadvantaged residents, and provide public retirees with a more secure and sustainable retirement system.

Next, Madigan’s rules and broken budget process should be replaced with systems that share power among the people’s representatives and discourage mismanagement. This starts with reforming the House rules, strengthening the balanced budget requirement, and capping annual spending increases at the rate of growth of the economy.

Madigan’s decades at the height of political power and near-monopoly control of the state legislature have left Illinois drowning in debt and its citizens fleeing to other states. His eventual departure from office – whenever that happens – could be a catalyst for lasting change.